The Bronze Age Collapse was a period of political and societal collapse across much of the eastern Mediterranean and Near East around the 12th century BCE. It saw the disappearance of major cultures such as the Mycenaeans, Hittites, and Ugarit. Ancient Egypt was also affected by the collapse, but with less devastating and therefore often overlooked results. Richard Marranca sat down with Dr Kara Cooney to talk about Egypt during the Bronze Age Collapse, including when it happened in Egypt and the evidence for its devastating effects. In particular, they dive into how the period of scarcity following the collapse led to organized grave robbing, not by poor workers but by the country’s new leadership, who reused and repurposed royal grave goods to reinforce their claim to power.

Dr Kara Cooney is a Professor of Egyptian art and architecture at UCLA, specializing in funerary practices and coffin studies. She produced a comparative archaeology TV series for the Discovery Channel called Out of Egypt in 2009, which is now available on Netflix. She is currently researching coffin reuse between the 19th and 21st dynasties, and the socioeconomic and political turmoil that characterized the period. Her recent publications include “When Women Ruled the World: Six Queens of Egypt” (2018) and “Recycling for Death: Coffin Reuse in Ancient Egypt and the Theban Royal Caches” (2024).

The Bronze Age Collapse in Egypt

RM: Can you tell us a bit about the Bronze Age Collapse and what it looked like in ancient Egypt?

KC: I think a lot of people were recently introduced to the subject by Eric Cline’s book, “1177 BC: The Year Civilization Collapsed.” This is often imagined as a horrific moment in history, but it was a long-term development that took centuries to come to fruition. The more I work with the material from ancient Egypt, whether it’s coffin reuse or Sea People invasions or even the Amarna Period, I see the Bronze Age collapse as having planted its seeds way before it became visible.

The seeds were probably planted and germinating at the end of the 18th dynasty (c. 1550-1292 BCE). The Sea Peoples show up in the Amarna Letters as mercenary-type peoples. The letters also mention the lesser-known Apiru. In the letters, all of these Middle Eastern or Near Eastern rulers are saying that they have been taken over by the Apiru or that they have toppled another kingdom. So it all started during the 18th dynasty, and then increased during the Ramesside 19th dynasty (c. 1292-1191 BCE), and ended in civil war during the 20th dynasty (c. 1189-1077 BCE). This was followed by the breakdown of government systems and institutions, such as the temples and the kingship.

This is the Bronze Age collapse from the Egyptian perspective, but it would swallow up the entire Mediterranean with conflict and drama, arguably starting around 1300 BCE and then continuing on until even 1000 BCE, a longer timespan than I think most historians would grant it.

RM: What about Ramesses and the Bible? Is there anything in the Bronze Age Collapse that speaks to those connections?

KC: In the late 20th century, it became very unfashionable to look at the Bible as a historical source. Academics have turned away from identifying historical events in the Bible, except in 2 Kings, where Taharqa can be identified as a real person, and the Assyrians did have battles in Egypt. However, despite its historical references, the Bible has a mythical edge, as seen in the parting of the Red Sea and the swallowing of an army, which leads people to turn away from it as a real historical source, especially “scientific” historians who don’t want to be associated with evangelical truth-seekers.

This is also coupled with the trend to bring the supernatural into Egyptian history, with suggestions that the pyramids were built by aliens and drawing connections with the lost city of Atlantis. This has culminated in academics pushing back against examining the Book of Exodus through a historical lens.

I don’t understand why it’s so shocking and horrible to see the Book of Exodus as part of the larger story of the Bronze Age Collapse, because it’s all right there. You have the diminishment of the strongest power in the ancient world, Egypt. The pharaoh is doing things that don’t seem clever. Something’s happening. Exodus reflects people watching these events unfold and trying to understand them. They’re like, “Oh, my God, the richest superpower has fallen, has been laid low. How could this happen?”

There are kernels of information about the Bronze Age Collapse within the story. It mentions the Ramesside city of Pithom and Per-Ramesses, major centers of power during the 19th and 20th dynasties. Which king is it that features in the story? I think it’s the wrong question to ask. Pharaoh is Pharaoh. It could be Seti I. It could be Ramesses II. It could be Merneptah. It could be Ramesses III. It’s all of them. And it’s all of them dealing with the crisis of the Bronze Age Collapse.

The Amarna Letters and International Politics

RM: Can you delve into some of the other things revealed by the Amarna Letters?

KC: The Amarna Letters reveal how vassal kings could send their sons to the Egyptian court to grow up, become Egyptianized, and then bring Egyptian ideas back to their own kingdoms. But it gets to a point where the West Asian vassals are: “I’m done with this. I’m done with listening to what the king has to say. I’m done with being part of this scheme.” And you see decentralization and disconnection happening among this international courtier class.

When you read the Amarna Letters, you see that everyone is sleeping with everyone else. There are diplomatic marriages between Babylon and Egypt, as well as between Mitanni and Egypt. There are numerous princes and princesses being born, all of whom are connected and related. And I actually think Nefertiti is a foreign princess brought to Egypt for a diplomatic marriage; I’ll argue this in my forthcoming book. However, these strong international connections are beginning to deteriorate.

The Bible’s explanation for this is that it is God’s will, and this reflects the ancient mindset. It is a way to understand massive events, such as: “Why did Ugarit fall? Why did Mycenae fall? Why did all of the cities along the coast of West Asia become replaced by new elites? Why did Egypt have its own kingship replaced?” People often say that when the Sea Peoples invaded, Egypt was the only one that didn’t fall. But Egypt’s ruling class fell. The 21st dynasty (c. 1070-945 BCE) kings of Tanis were called Libyans, and they were Sea Peoples.

Collapse and Grave Robbing

RM: What about the Tomb Robbery Papyri? Do they provide evidence for the collapse?

KC: The Tomb Robbery Papyri is not one papyrus but dozens that relate to tomb robbing trials during the 20th and 21st dynasties. They’re so interesting because they describe a bunch of rich, entitled elite officials who are systematically plundering the Valley of the Kings and vying for power in a new political system. Looking at it from this perspective changes everything about the Tomb Robbery Papyri.

Previously, Egyptologists had looked at those texts and thought, “Oh, my goodness, the necropolis security is broken down. These hordes of poor people are going into the Valley of the Kings and just stealing whatever they want.” But the Tomb Robbery Papyri reveal officials working against each other for their own benefit.

People are sent to Thebes to investigate, and all people who end up being investigated are associated with the High Priesthood of Amun. They could be a guardian, a craftsman, or something else, but they seem to have the priesthood of Amun as their patron. They seem to be offered up as scapegoats, and they are interrogated and tortured, and names are named.

Royal Mummy head of Thutmose III, from the original catalog of the Cairo Museum’s The Royal Mummies, only his head was photographed as the body was in such poor condition. Source: University of Chicago Library

It’s shortly after these documents were written down, in the reign of Ramesses IX, that we have actual hard evidence for the tombs of Ramesses II, Amenhotep III, and Thutmose III being systematically moved.

RM: So are the contents of the tombs being sold or moved to keep everything safe?

KC: When Howard Carter found Tutankhamun in 1922, it took him ten years to clear that tomb. Of course, he was an archaeologist working with care and precision, aiming to preserve the objects. In the ancient world, they were less interested in that. They wanted the gold. To have gotten to the bodies of Thutmose III or Ramesses II, the robbers had to remove them from their nesting shrines, sarcophagi, coffins, and masks. They’ve gotten in there and disassembled everything. And when those bodies were moved, they were stripped of all of their wealth and rewrapped. Egyptologists used to think, “Oh, that means that the hordes of Egyptians took them and then they were piously rewrapped by the High Priesthood of Amun.” But now we see that it was the High Priesthood of Amun that was precisely the institution responsible for taking the gold and treasures.

RM: So, the elite had a huge role in robbing the royal tombs. Is there much supporting evidence?

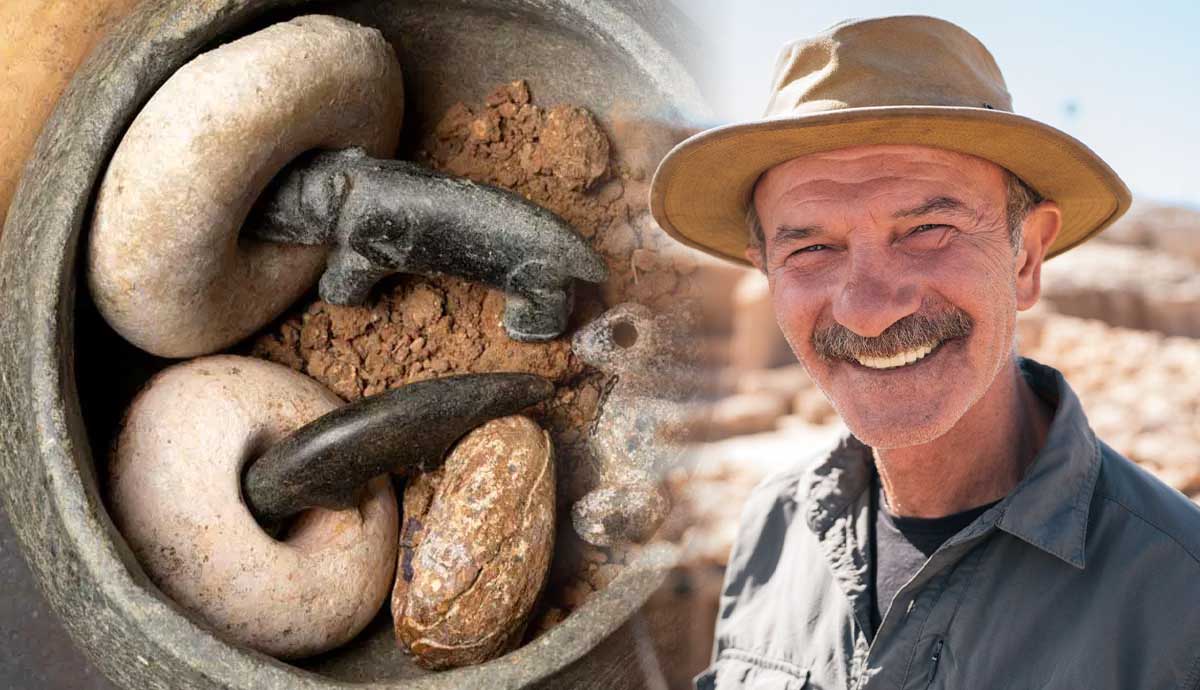

KC: Absolutely. The royal tombs at Tanis, belonging to the 21st dynasty, were found intact, a rarity. These foreign claimants to power needed to bury themselves with pomp and circumstance, so they took previous burial goods and used them for their own burials. There is a sarcophagus reused in Tanis that was recarved for Psusennes I, one of the first kings of the 21st dynasty, and it first belonged to Merneptah from the 19th dynasty. It was one of his four nesting sarcophagi, massive stone objects that are as big as your living room, placed inside one another like a Russian doll. That, to me, smacks of extraordinarily defensive burial tactics by the 19th dynasty kings. In contrast, we don’t have any Ramesside coffins preserved. I think this is because they were made of solid, like the inner coffin of Tutankhamun.

But if, like Merneptah, you have four nesting sarcophagi, what was in there that you needed to protect and move into that tomb? And how do you get the lid off? Incredibly, the grave robbers did get it out whole. Most of the other sarcophagi were broken apart to access what was inside. It seems that only this one was moved to Tanis and reused.

At this time, diplomatic relations exist between the foreign pharaohs in Tanis and the High Priesthood of Amun in Thebes, with everyone intermarrying. The Theban noblewoman Nodjmet bore Pinedjem I, a ruler of southern Egypt, as the high priest of Amun in Thebes, and she was also the mother of one of the kings of Tanis. They are in a time of scarcity, with no new stone and gold coming out of the mines, so they are working together to reuse earlier material. “You need a sarcophagus? Here’s a sarcophagus.”

No one has done this work yet. I can’t wait for the technology to examine the gold and silver objects from the royal burials at Tanis, published by Pierre Montet. The gold is thinner. The gold has a weird hammered quality. The gold lacks the skill of application evident in the tomb of Tutankhamun, our only fairly intact New Kingdom tomb. I know that gold is recommodified gold from the Valley of the Kings. Can I prove it? Not with the technology that’s available now. Hopefully, in the future, we will be able to pinpoint the exact sources of the gold and how many times it was reused.

Examining the burials of the high priests of Amun, including men such as Pinedjem I, Pinedjem II, and Masaharta, as well as the women and children buried with them, reveals that all are interred in reused coffins. This suggests they had no access to wood. The sycamore and acacia stands that must have been growing in the Delta were either repurposed for military needs or burned, or both. So, there is no new wood coming into Egypt. The trade from Lebanon in cedar wood and fir has been shut down. We can see that very clearly in the Story of Wenamun. So even these very wealthy, connected men are burying themselves in pieces of their rich ancestors’ coffins.