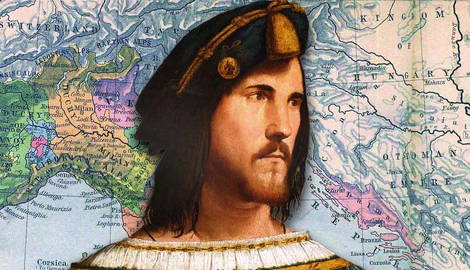

Born into a powerful family that controlled the papacy and much of the power structures of Renaissance Italy, Cesare Borgia was a powerful player in the peninsula. The son of the most powerful man in Christendom, Cesare made his way in the world through ruthless political scheming. Singularly ambitious, he served as an inspiration for Machiavellian practices that played a huge part in the politics of the region.

A Distrusted Family

Even the circumstances of his birth were open to derision from pious sectors of society. Cesare was born on September 13, 1475, as one of the four illegitimate children of Cardinal Roderic Llançol i de Borja (commonly known as Rodrigo Borgia) and his mistress, Roman aristocrat Giovanna “Vannozza” dei Cattanei.

As a noble family from Valencia in Spain, the Borgias were already under suspicion by those who did not see the papacy as the place for a foreign pope. When Rodrigo did become Pope Alexander VI, there was significant dissatisfaction from many nobles who disliked Spain.

A precedent had already been set by the fact that another member of the Borgias family, Alfonso, Rodrigo’s uncle, had become pope in 1455, and his three-year reign had been stained by corruption. It was also widely believed that Rodrigo had bribed his way to the top, setting the stage for a papal rule that would be mired in corruption and nepotism.

Rodrigo wished to keep his power, and his enemies wished him to be deposed. The dynamic lent itself to the machinations of scheming and plotting that would go far beyond the limits of what was legal. For Rodrigo, Cesare proved to be extremely useful, and he had grand plans for his sons.

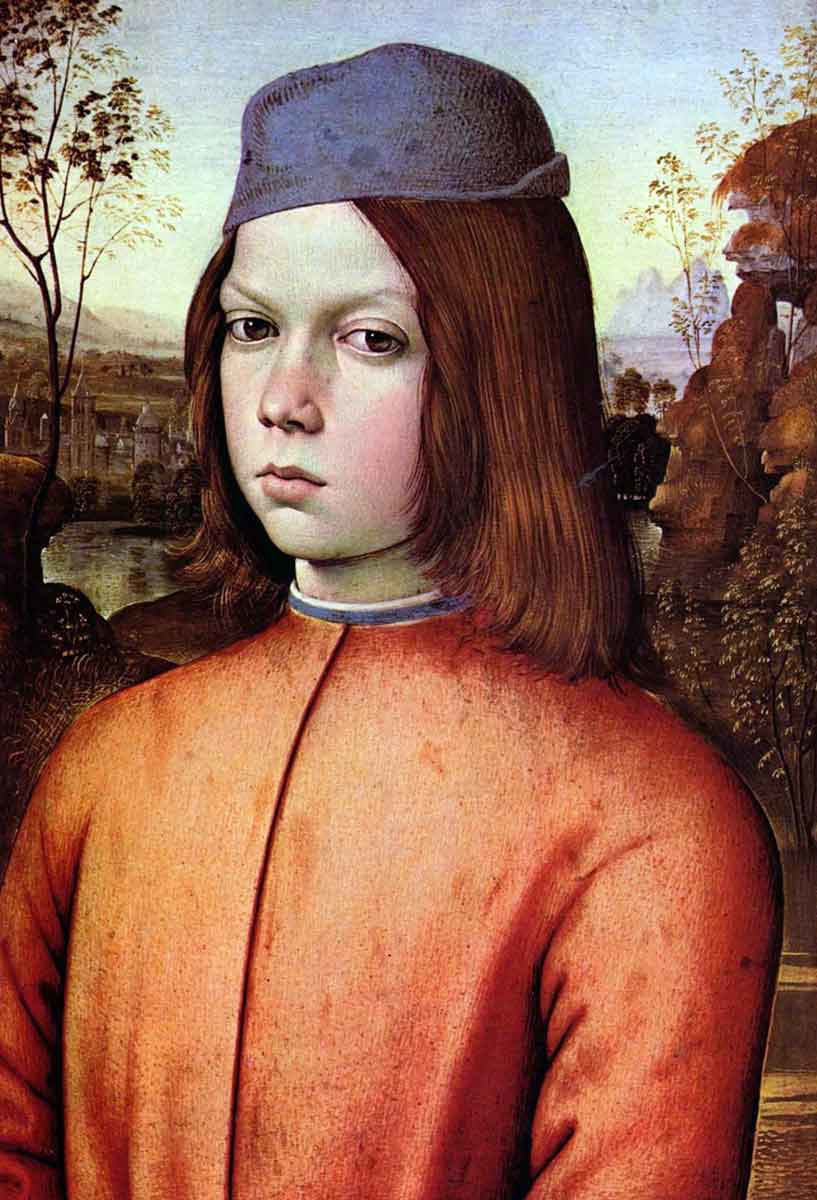

Long before Rodrigo became pope, Cesare received an outstanding education, learning to read Classical Greek and Latin. He was also given physical training. He excelled, becoming a very competent fighter in the process. In 1489, he entered the University of Perugia and was, by the influence of his father, elected bishop of Pamplona, although he was too young to take up this office immediately. He also spent time studying law at the University of Pisa.

With so much education and training under his belt and an office of high standing already waiting for him, Cesare was sure to become a hugely successful man.

A New Pope

On July 25, 1492, Pope Innocent VIII died. Two candidates had emerged as the frontrunners to succeed him: Giovanni de la Rovere and Rodrigo Borgia. Through allegations of bribery, Rodrigo became the new pope (Alexander VI), and within a matter of weeks, he succeeded in appointing Cesare to the position of Archbishop of Valencia. Cesare was just 17 years old at the time. At the age of 18, he became a cardinal.

In 1493, the Italian peninsula became a place of open conflict as the French, under King Charles VIII, joined with Ludovico Sforza, Duke of Milan, in a planned invasion of Naples. Pope Alexander did not condone this action, and on December 31, the French entered Rome, where looting took place. To avoid bloodshed, the pope offered Cesare as a hostage on the condition that he remain on Italian soil. Charles VIII agreed, and with Cesare in tow, the French army marched into Naples and sacked it.

Alexander, like many Italian nobles, was concerned about French domination in Italy and sent requests for help throughout Europe. His words found fertile ground, and the Holy League (or League of Venice) was formed against France, consisting of the Papal States, the Holy Roman Empire, Venice, Naples, Spain, Florence, and even Milan, which had switched sides. Meanwhile, Cesare managed to escape and make his way back to Rome. In 1496, the French were eventually forced out of Italy.

The Borgia Brothers

Despite his martial and physical prowess, Cesare had originally been groomed for an office in the church, while his brother, Giovanni, was marked for greater things. Giovanni, known to his family as “Juan,” was given status as the pope’s favorite son. He became the Duke of Gandia, as well as Gonfalonier of the Church, and Captain General of the Church. Through these appointments, Giovanni controlled the armies of the Papal States.

He inherited the title of Duke of Gandia from his half-brother, Pedro Luis, who left it to him in the will, bypassing Cesare, who, as the eldest child, was said to have been jealous. In 1496, Giovanni led the papal armies against the rival Orsini family in the first of Pope Alexander VI’s campaigns.

In 1497, however, Giovanni was murdered. After an extensive search, his body was found in the Tiber River. He had been stabbed nine times, and his purse was still full of coins. It was never determined who the culprit was or why he was killed, but there were numerous theories that remain as such today. One theory suggests that Cesare was the killer, but there was little in the way of a definitive motive, as Cesare was likely to gain secular power despite Giovanni being the favorite son. Rumors spread through Roman society that Cesare was the killer, but nothing could be proven.

Nevertheless, with Giovanni no longer alive, Cesare became the focus of his father’s attention for familial success. In 1498, at the age of 23, Cesare was released from his ecclesiastical duties and shifted his focus towards success in the military.

Regal Ambitions

Cesare was well aware that much of his power and standing was derived from his father’s position as pope. Cesare knew that as soon as his father died, his privileges and power would evaporate, so the young Borgia made efforts to create a name for himself based on his own means. One of his aims, supported by his father, was to carve out a dukedom for himself in the lands of Romagna. Marriage, however, was a pressing concern.

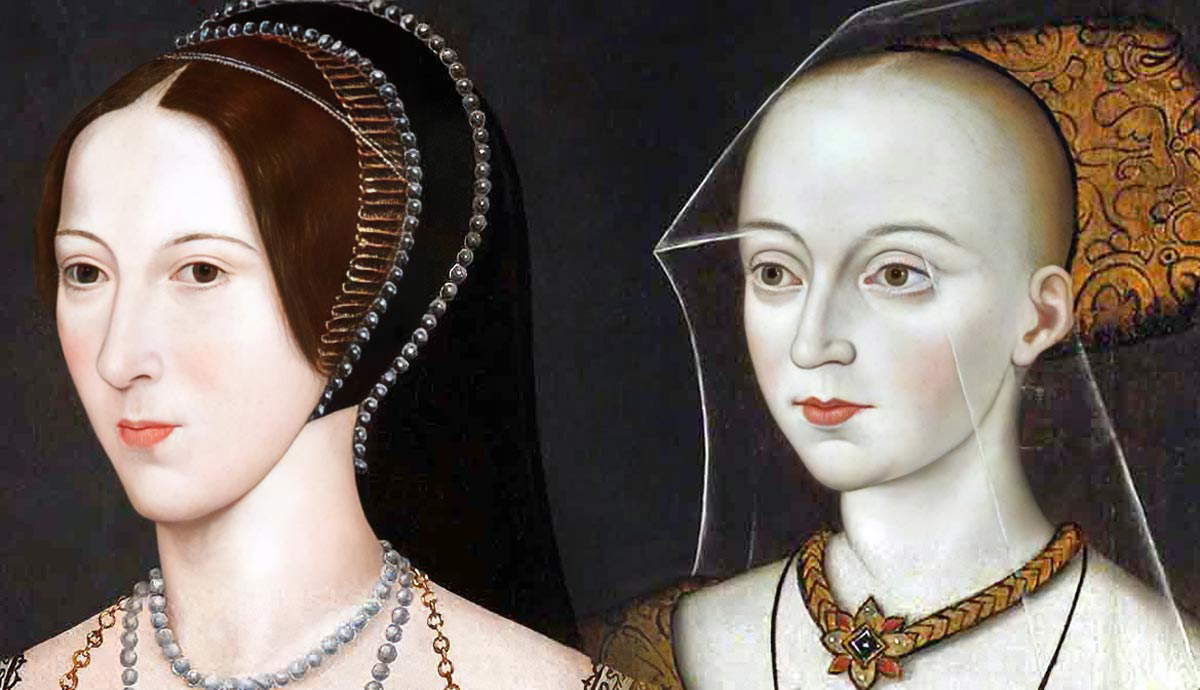

He sought the hand of Princess Carlotta, the daughter of the king of Naples, but this idea never came to fruition. Rebuffed by the King of Naples, who claimed that “no bastard son of a priest” would marry his daughter, Cesare was forced to look elsewhere.

Fortune and circumstance favored him in the Kingdom of France, where King Louis XII, who had recently ascended the throne, sought an annulment of his marriage to Joan, who was alleged to be barren. The king wished to marry Anne of Britany and, in so doing, lay claim to the Duchy of Britany.

Pope Alexander, seeking land and titles for his son, annulled the marriage. In return, Cesare became the Duke of Valentinois, and the young Borgia married Charlotte d’Albret, sister of the king of Navarre. With land and a ducal title, Cesare had a foundation for his regal ambitions.

For the pope, the promise of French military assistance in regaining control in the Papal States was also of prime importance. Many of these lands had become controlled by semi-independent vicars, and the pope saw this as an affront to his legitimacy.

War

At the head of the papal army and a considerable contingent of mercenaries as well as French and Swiss troops sent by Louis XII, Cesare began a military campaign to regain control of papal lands.

In 1499, he attacked and occupied cities in Romagna and the Marches. This campaign was accompanied by an invasion of Italy by Louis XII, who had made a pact with Venice against Ludovico Sforza, the Duke of Milan and an enemy of the Borgias. In September 1499, the Venetians soon marched into Milan followed by the French, accompanied by Cesare, a month later.

Ludovico Sforza opted for exile in Austria while many Milanese, who did not want to be ruled by the French, also left the city. One of these emigrants was Leonardo da Vinci, who later worked for Cesare for a few months in 1502 and 1503 as a military engineer and architect.

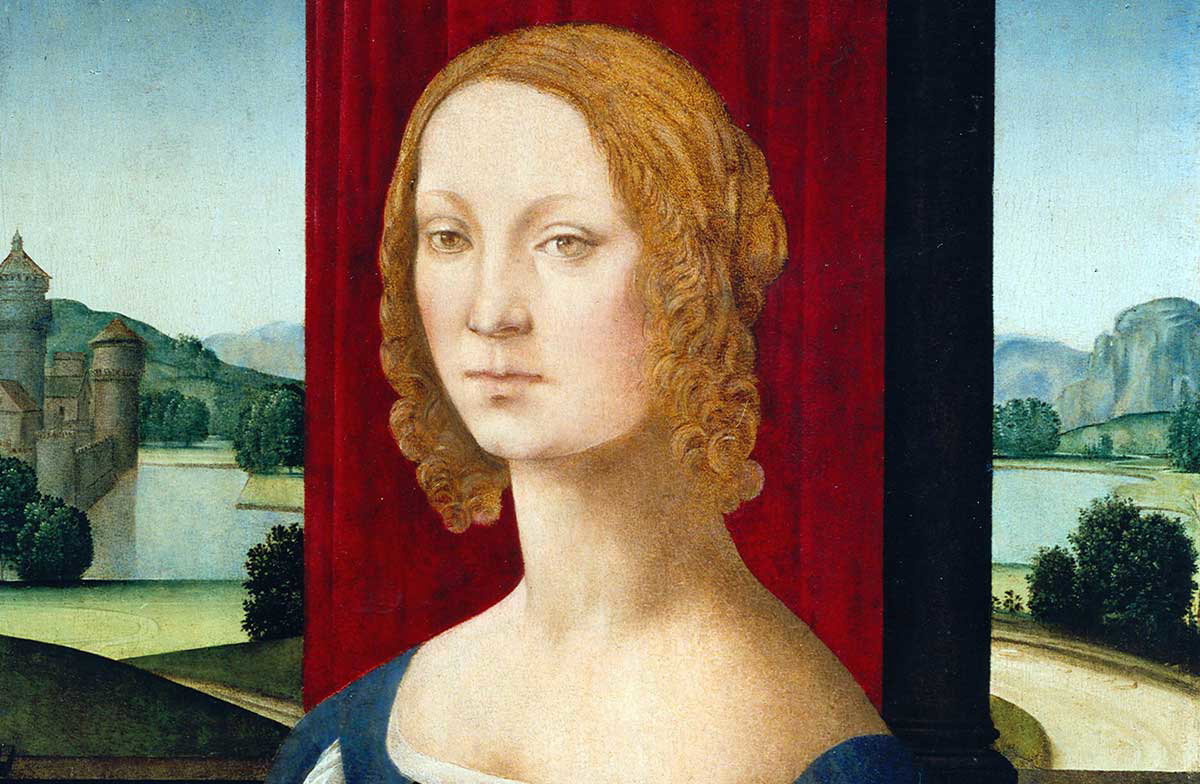

Caterina Sforza, the Countess of Forlì and Lady of Imola, was the next target of the Borgias, and Cesare led his forces through Florence (with permission from Florentine diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli). The papal forces laid siege to Ravaldino, the fortress in the city of Forlì where Caterina made her stand. After the siege had begun in December 1499, she tried to capture Cesare when he came close to the fortress to talk to her, but the attempt failed, and the siege continued with cannon from both sides being the dominant factor. Damage to the fortress, however, was repaired in quick order every time the French cannon paused.

Cesare ordered the bombardment to continue without pause for several days and nights until the walls gave way. On January 12, 1500, Cesare’s forces stormed through the breach in the walls and won a quick victory. Caterina surrendered to the French but was turned over to the papal forces. Shortly afterward, Ludovico returned to Milan, and Cesare recaptured the city. The Sforzas had fallen, and the Borgias had triumphed over a dangerous enemy.

The war, however, continued against the Borgia’s other enemies, and Cesare took the lead in restoring Borgia control in Rimini, Pesaro, Faenza, Urbino, Camerino, and Senigallia. While achieving these victories, the pope named Cesare Duke of Romagna.

A Clever Leader or a Dissolute?

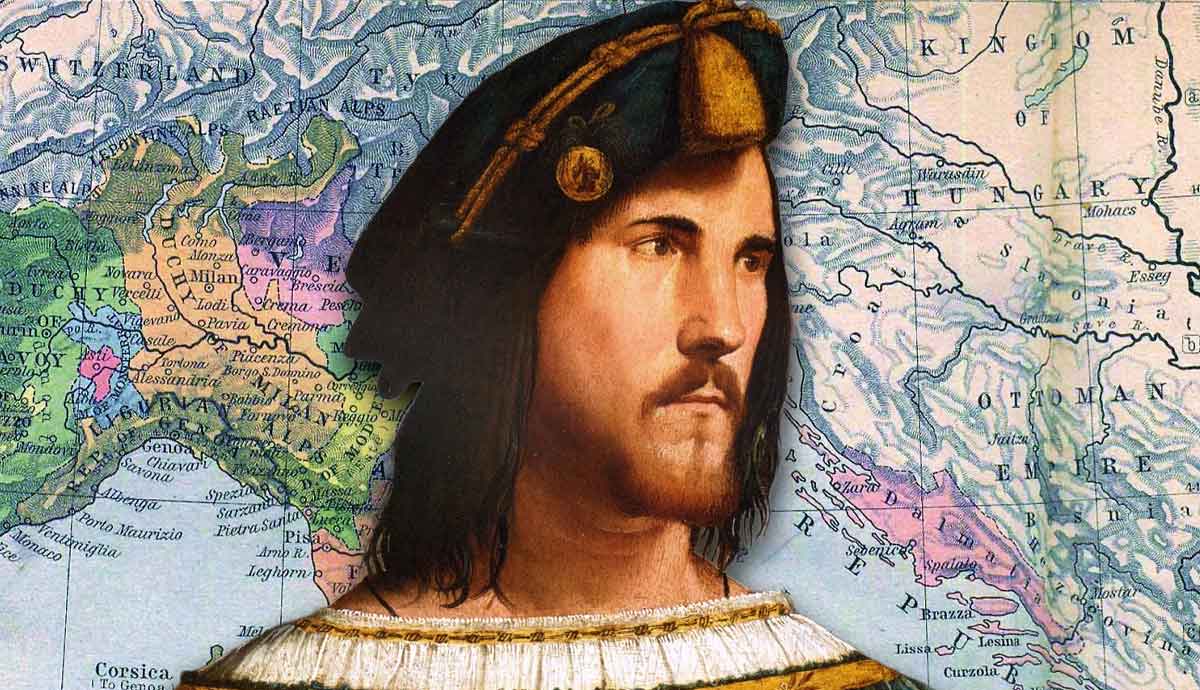

Among those observing the martial exploits of Cesare and his administrative efforts following consolidation in Romagna, was Machiavelli, who drew great inspiration from the man, extolling his abilities as a highly capable and effective leader.

Beyond Machiavelli, however, not all portrayals were of such high praise. Alexander and Cesare had, in their quest for power, accumulated much hatred from those who opposed them, and the Borgias were the target of a propaganda campaign that painted them in an unflattering light.

Cesare was painted with a brush of lust and cruelty and was rumored to have been behind many assassinations. How much of this was true is unknown, but it is certainly possible that Cesare was behind the assassination of Alfonso, the Duke of Bisceglie, who was the second husband of Lucrezia Borgia, Cesare’s sister. While the exact truth remains a mystery, Cesare did argue that Alfonso had tried to assassinate him with a crossbow.

Whether true or not, the Borgias certainly gained a reputation for licentiousness. Papal Master of Ceremonies, Johannes Burchard, wrote of the “Banquet of Chestnuts,” an orgy that took place in the apostolic palace on October 31, 1501, with the pope, Cesare, and Lucrezia in attendance. Prizes were handed out to the men who could perform the most times with the 50 courtesans and prostitutes present.

Cesare fathered eleven illegitimate children during his lifetime, as well as one legitimate child. His sexual exploits led to him contracting syphilis, which scarred his face. In later life, he wore a mask in public to hide his disfigurement.

The Fall of Cesare Borgia

As a military man, Cesare became a figure who commanded great respect. Gone were the flamboyant robes of the ecclesiastic, and in their stead, Cesare cut an austere form in his choice of color: black.

His power and prestige, however, were not altogether his own. He still relied on support from his father, whose office gave Cesare great legitimacy. However, in 1503, the power dynamic changed rapidly.

While Cesare was sick and suffering from malaria, he received news of his father’s death. How Alexander VI died is still a subject of great debate. Contemporary accounts suggest that he may have been poisoned. Cesare had nothing to worry about from the new pope, Pius III, who reconfirmed Cesare as the head of the papal armies.

Alas for Cesare, Pius III was only pope for 26 days. He died from a septic ulcer in his leg and was succeeded by Giuliano della Rovere, who had nothing but loathing for the Borgia family. Immediately, Cesare lost the backing of the church as well as his position as head of the papal armies.

Cesare was arrested but was released after agreeing to surrender the cities he had captured. He fled to Naples, but danger was waiting for him there too. Cesare gambled on the support of Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, who he had hoped would join him in an alliance against the pope. Instead, the Spanish general had Cesare arrested. Cesare was kept imprisoned in Spain until he escaped from the Castle of La Mota in 1506. He made his way to Pamplona, where he met with King John III of Navarre, his brother-in-law, who hired him as a military commander.

On March 11, 1507, during a siege, Cesare was separated from his soldiers after attempting to chase down a group of enemy knights. Upon realizing that he was alone, the knights set upon Cesare and killed him. His body was stripped, and he was left naked with only a tile covering his genitals.

Cesare was 31 years old when he died.

Cesare Borgia’s Legacy

To some, Cesare Borgia was an inspiration. To others, he was a lesson. And for many, he was simply an interesting historical character. He played an important role in Italy’s history and was the subject of writing from Machiavelli to Friedrich Nietzsche.

In modern times, the Borgia family has found much interest in fiction and non-fiction, and Cesare serves as a vital component to several television shows about the Borgias. Apart from representations in books and on screen, Cesare also appears as the principal antagonist in the 2010 video game Assassin’s Creed: Brotherhood.

Having been born into the Borgia family, there was little doubt that Cesare would live a life filled with political intrigue and mortal danger. His story and his character, shaped by propaganda as well as reality, have endured through the ages to the point where his fame (and infamy) now rivals that of when he was still alive over 500 years ago!