The time between the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE and the Renaissance in the late 15th century CE is often categorized as a “Dark Age.” This highly misleading name reflects the perception that this was a period of cultural decay, stagnation, and malaise. This results from the confusion that fell on Europe following the fall of Rome, but it did not take almost a thousand years for European culture to recover. The legendary Frankish king Charlemagne spearheaded efforts to stabilize the political, economic, military, and cultural chaos after Rome’s collapse. This led to a period of cultural revolution between 750-900 CE known as the Carolingian Renaissance.

The Franks Take Rome

The Roman Empire reached its height in the 2nd century CE, and then began a slow and painful decline. After near constant civil wars, economic crises, and barbarian invasions, the empire split between the Eastern half centered on Constantinople, which would continue to exist until the 15th century, and the Western half centered on Rome, which limped on as pieces were hacked off by invading Germanic tribes. In 476 CE, the final deathblow was struck when Odoacer, a Germanic chieftain, overthrew Romulus Augustulus, the last Western Roman Emperor. For all practical purposes, this act ended the Western Roman Empire and signaled the beginning of the Middle Ages. The Roman Empire, once the dominant power in Europe, was divided among migrating tribes such as the Goths, Vandals, and Saxons.

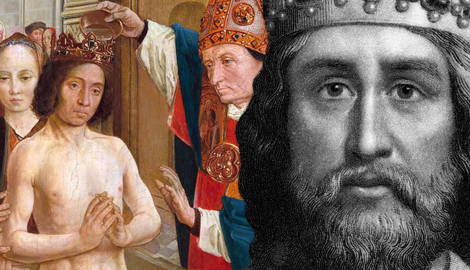

One of these migrating tribes was the Franks. They first appear in the historical record in the 3rd century CE. As Rome crumbled, they carved out their own territory in Gaul, modern-day France and Belgium, displacing other barbarian groups who were also migrating for more land. While many of the Germanic tribes had converted to Arianism, a heretical branch of Christianity, the Franks were still pagan. The Catholic Church, now taking on the burden of administration left behind by the dying Romans, convinced Frankish king Clovis to convert to Christianity. With his conversion, the relationship between the Catholic Church and the Franks was secured.

Clovis was part of the Merovingian dynasty, which extended its territorial holdings to include most of what is now France and eastward past the Rhine into Germany. By the 8th century, the Merovingian dynasty was replaced by the Carolingian dynasty, including their most famous member, Charlemagne. Working with the Church, he began the seemingly insurmountable task of bringing order to Europe in the wake of Rome’s collapse. Even centuries after its fall, Europe had not recovered and was gripped by confusion and disunity. His efforts would kick off the Carolingian Renaissance, a rebirth of culture and political stability that dragged Europe out of the morass of Rome’s fall.

Silver and Steel

As a Germanic Frankish king, Charlemagne was expected to be a warrior, leading his armies against the enemies of his realm. Fortunately, there was no shortage of these, and he spent a large portion of his reign in the field. His campaigns took Frankish armies across the Pyrenees into Spain to fight the Muslim Umayyad Caliphate, which was immortalized in the epic poem The Song of Roland. He also turned his attention south to northern Italy, where he fought the Lombards. His greatest rivals, however, were the Saxons in Germany. These pagans were a constant headache for Charlemagne, and his battles against them were brutal, with thousands dying over several decades.

To build a military to fight these threats, Charlemagne relied on an early form of the feudal system that would later characterize the socio-economic and political situation in Europe during the Medieval era. In theory, all freemen were liable to be called up for military service and had to provide their own equipment at their own expense. To sustain these men, especially armored horsemen, a proto-version of knights, they would be given land grants that provided income and resources. Local areas were overseen by counts, a class of nobility that answered to the king and represented Charlemagne’s authority. These lands helped fund the crown through a series of taxes, tolls, and other fees.

For this system to make any kind of sense, there needed to be economic stability. During Rome’s decline, inflation and economic instability contributed to the empire’s fall. The wake of this collapse led to a convoluted system of coinage that was better at giving accountants headaches rather than fostering trade.

Picking up where his father left off, Charlemagne standardized the coinage of the kingdom, basing it on silver. The coinage would be standardized into a duodecimal system. Meaning one twelfth in Latin, coins would be based on the denier, twelve of which would equal one sous. Twenty sous would equal one livre. This remained in place, more or less unchanged, until the French Revolution. Coins would be made to a standard size and weight at designated royal mints to ensure quality, prevent counterfeiting, and keep the precious metal content consistent. With the military and economic reforms, the Frankish kingdom was able to focus on other matters that brought about a Renaissance of culture and learning.

Centers of Learning

One area that Charlemagne was consistently concerned with was promoting literacy. After Rome’s fall, the literacy rate dropped. Literacy was kept alive through the monasteries, with monks copying as many ancient texts as possible to preserve their knowledge. Charlemagne knew the power of writing and encouraged the learning of written Latin. This was done to streamline administration and for liturgical purposes, enabling clerics and priests to read and understand the material they were preaching to their flocks. Schools were established and repaired, and more students were enrolled to learn.

With more people able to read and write, administration was streamlined, and people living in distant parts of the ever-growing empire were able to communicate with one another more easily. Sending a letter is simpler than having a messenger memorize a message or speak face-to-face after traveling hundreds of miles. In addition to the schools, a Scriptorium was established, a center for the copying and writing of books.

During Charlemagne’s reign, there were many innovations to the written word that made reading easier. In ancient times, Latin would be written using a process called scripta continua. This meant that all the words would be written in a continuous stream. During the 7th or 8th centuries, Irish monks developed a system called scripta discontinua. This simply means that a space would be placed between each word. If you are reading this, you can understand how this simple innovation makes reading easier. This era also saw the use of the period, the comma, and the question mark, though they were a bit different than the punctuation marks used today. Still, these symbols added nuance to a manuscript that would otherwise be difficult to interpret.

This educational reform was overseen by a group of scholars whom Charlemagne gave precedence within his court. These men came from around Europe, especially from Italy, Ireland, Spain, and England. The most prominent of these was an Anglo-Saxon cleric from Northumbria named Alcuin. This monk wrote works on the lives of saints, Biblical commentaries, and religious tracts, and was well versed in geometry, astronomy, rhetoric, and other subjects. With these intellectual powerhouses directly influencing the king, it’s no wonder that education within the Frankish kingdom became some of the best in Europe.

Patron of the Arts

With the military situation under control, the economy stabilized, and ever-increasing literacy, the Franks were able to devote time to artistic pursuits. The new wealth and stability enabled Charlemagne, his nobles, and clergy to patronize artists, bringing sophistication and beauty. The Franks already had an artistic tradition. Like other Germanic tribes, they had a great fondness for metalwork, especially in silver and gold, and if possible, these would be encrusted in colorful gemstones. These would be used to embellish jewelry or weapons and given as gifts by the higher classes in society to their subordinates as a way to reinforce bonds of loyalty. This tradition continued under Charlemagne, but with a new twist.

Because of Charlemagne’s close association with the Catholic Church, religious items were adorned with fine metalwork and jewels. These included holy books, reliquaries to house relics, chalices, crosses, and other religious items. Carved ivory figurines and paintings depicting the human form were also a common expression of Carolingian artwork. Even the books themselves would be decorated, with the innovation of illuminated manuscripts, books whose pages were richly illustrated with vibrant colors and exquisite calligraphy. These items would be given as gifts by Charlemagne to monasteries that he patronized in a similar way as a jewel-encrusted sword would be given to one of his warriors.

In addition to art, architecture was also revived during this period. It borrowed heavily from the Byzantine Empire as well as the classical world. Churches and monasteries were made featuring columns and were round or octagonal in shape, with domed roofs supported by barrel vaults. One surviving example, the Palatine Chapel in Aachen, Germany, was the seat of Charlemagne’s power and still contains his throne. It inspired other palace and church designs throughout Europe in the coming centuries.

It All Falls Apart

In addition to these reforms, Charlemagne also centralized the government, standardized the legal system, and implemented other policies that helped to bring order to chaos. The stability created by his reign led to the Carolingian Renaissance, which saw a level of cultural advancement and sophistication that had not been seen since the glory days of the Roman Empire. Over the coming centuries, the innovations made under Charlemagne’s reign would inspire art, architecture, and learning throughout Europe. His government reforms laid the groundwork for the feudal system, and variants of his economic policies would become the norm that others tried to emulate. Still, despite his efforts, this wasn’t enough to save the Frankish kingdom.

When Charlemagne died in 814, the kingdom was split between his sons, dividing the once mighty empire into separate, smaller nations. At the same time, there were a number of outside threats, such as the Saracens and the Vikings. The Norsemen fell on Europe, and the now rich monasteries were an easy target for their raids. It would take several centuries to finally end this threat, and it was a major blow to the advancements made during Charlemagne’s time on the throne.