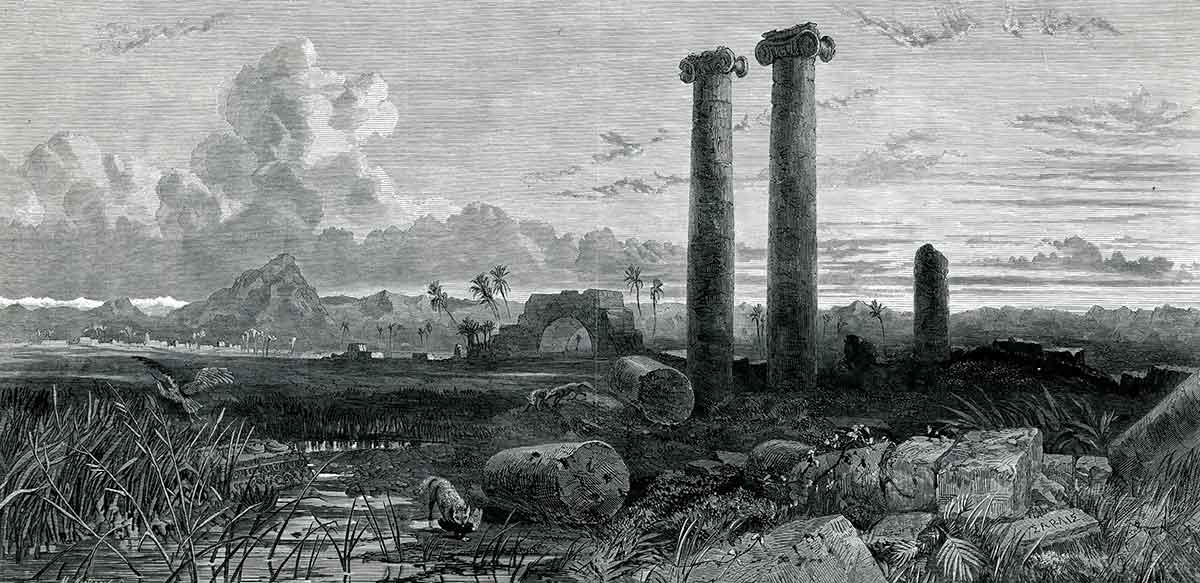

Croesus ruled the kingdom of Lydia from 560 BCE to 546 BCE. His capital, Sardis, was a prosperous cultural center renowned for its wealth, architecture, and thriving economy. Under his rule, Lydia became one the most powerful empires in the ancient world, controlling key trade routes and abundant natural resources. Croesus’ name became synonymous with wealth, but he became enamored with his own success. His arrogance led him to challenge the budding empire of Persia, a decision that would ultimately lead to the downfall of his empire. The Greek historian Herodotus (5th century BCE) wrote about the life of Croesus in his Histories. By Herodotus’ time, Croesus had become a legendary figure whose life was blended with myth.

Croesus of the Mermnad Dynasty

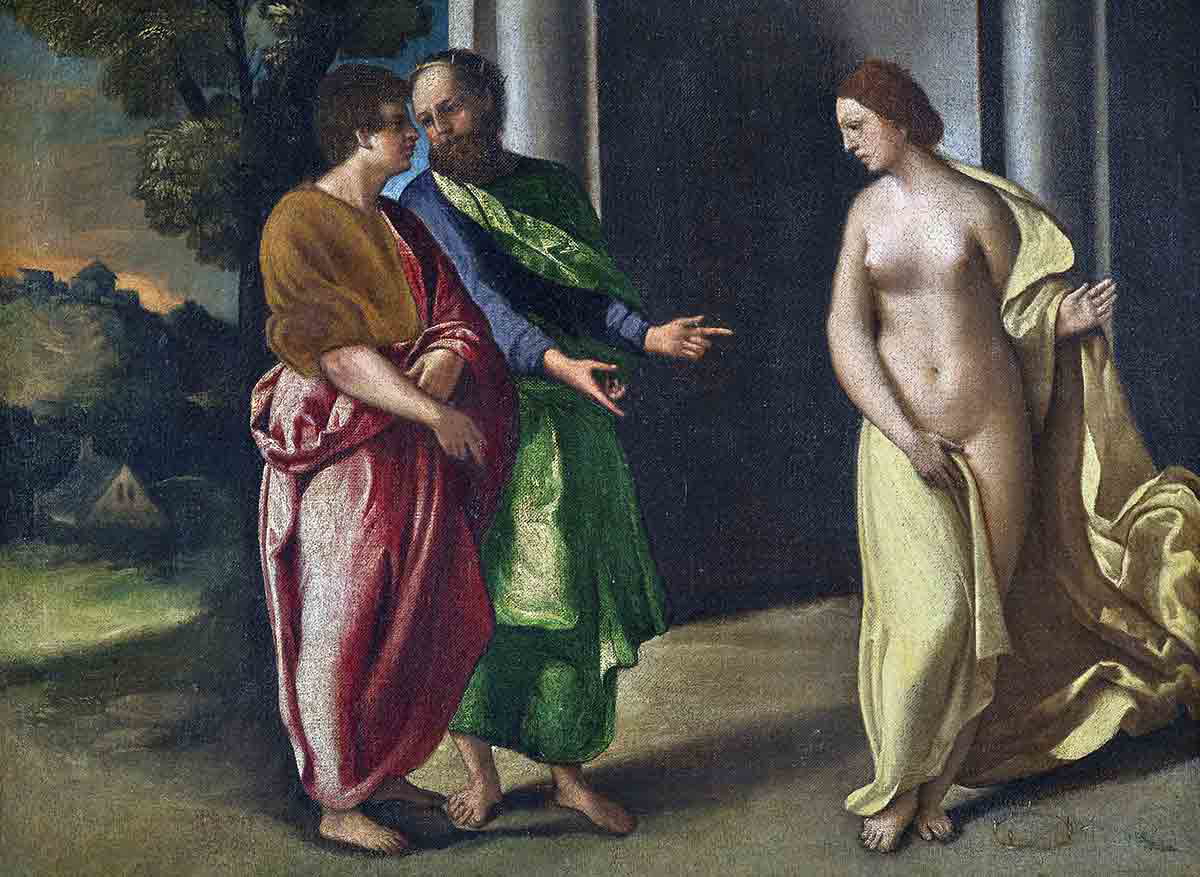

Croesus was part of the Mermnad dynasty. His ancestor, Gyges, was a bodyguard to King Candaules, a descendant of Heracles. The king was obsessed with his own wife’s beauty and wanted to prove to Gyges that she was the most beautiful woman in the world. In order to prove this, Candaules had a plan to allow Gyges to see his wife naked without her knowing. While Gyges initially refused, he soon gave in at the king’s insistence. The plan was to have Gyges hide behind the bedroom door and spy on the king’s wife as she removed her clothes. But the king’s wife caught a glimpse of Gyges as he slipped from the room and knew what her husband had done.

The next day, she summoned Gyges and presented him with an ultimatum: he could kill the king and take her as his own wife or be killed. To answer for the shame he had caused her and unable to persuade her to change her mind, he agreed to save his own life. They plotted to kill the king in the same way that the king made Gyges view his wife. Gyges hid behind the door, and once the king was asleep, he came out and stabbed him with a knife. Thus Gyges became king of Lydia, and his reign was ordained by the oracle at Delphi.

Rich Like Croesus

Five generations later, Croesus came to the throne at the age of 35 after the death of his father, Alyattes. He inherited an already powerful kingdom and wasted no time in pursuing his own imperial ambitions. He immediately set out to attack the Ephesians and then moved on to conquer the cities along the Aeolian and Ionian coasts. At its height, the Lydian empire was said to control all territories West of the Halys River.

Croesus amassed a vast fortune from the gold and silver mines in his territory, as well as from fertile agricultural lands. He could gather gold dust from the Pactolus River which flowed through his kingdom, the same river that the mythical King Midas used to wash away the curse of his golden touch. Lydia was also located at the center of a trade route that connected the East with the West. Croesus controlled the wealthy port cities of the Ionian coast, no doubt collecting taxes and tribute from all the merchants that passed through. All these factors made Croesus the richest man in the ancient world. His name became synonymous with wealth, coining the phrase “rich as Croesus.”

Meeting With the Sage

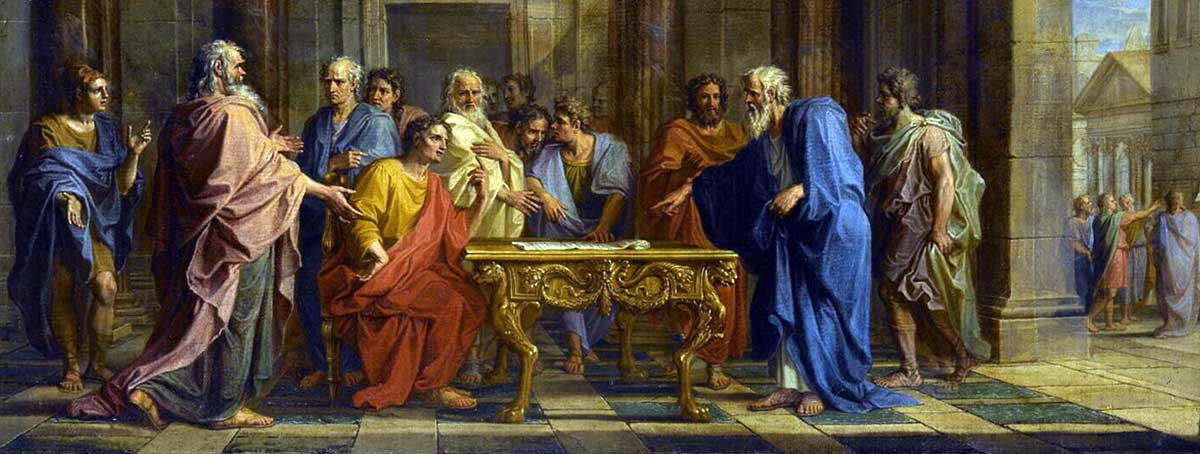

At the height of Croesus’ power and influence, he was visited by Solon, the legendary Athenian lawgiver hailed by Plato as one of the seven sages of Greece. Croesus hosted Solon at his palace and, after a few days of flouting his riches, asked the Athenian who he thought was the happiest man he’d seen, fully expecting to hear his own name. But Solon answered that it was an Athenian by the name of Tellus. He came from a prosperous city and had virtuous children, all of whom had children of their own. He had a glorious death in battle after routing the enemy and was buried with honors at public expense.

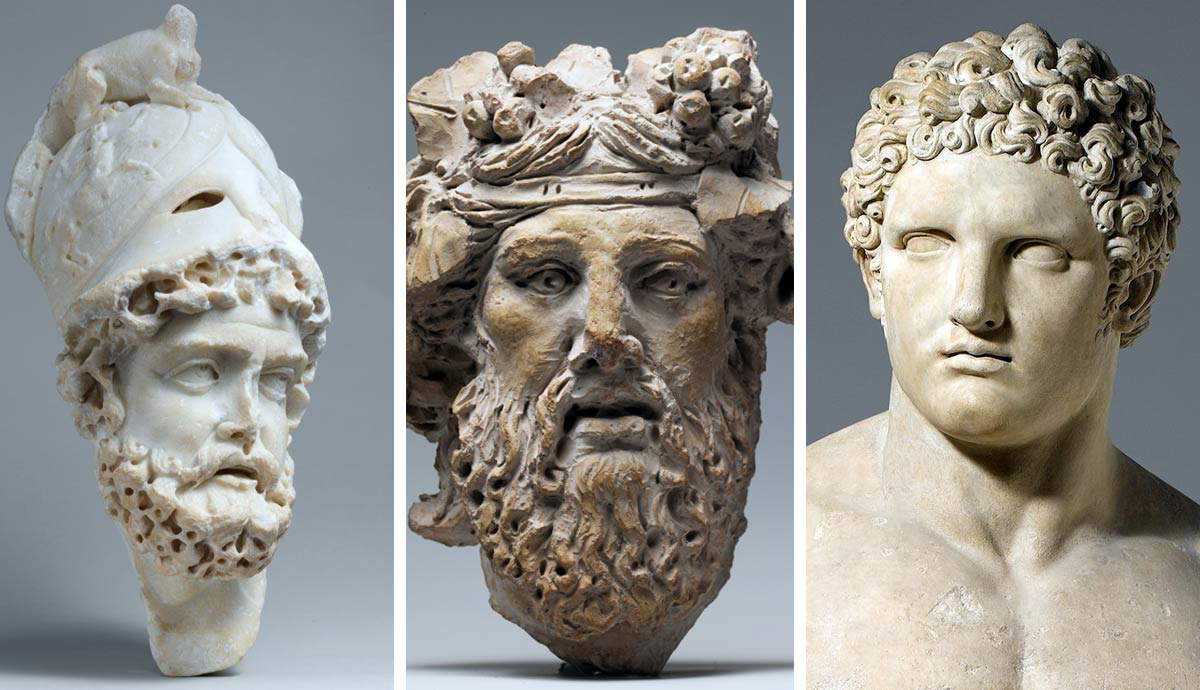

Assuming this was just a nationalistic bias, Croesus then asked who Solon thought was the second happiest, figuring that surely if he wasn’t first, he’d be second. Again Solon surprised him, answering that the second happiest were two brothers from Argos named Cleobis and Biton. These two brothers lived within their means, were physically strong, and had won athletic contests. During a festival for Hera, their mother had to be conveyed to the goddess’s temple by a team of oxen, but their oxen hadn’t come back from the fields in time, so they put the yoke over their own shoulders and pulled the wagon themselves. Upon completing this labor, they were praised and celebrated by the citizens. After making sacrifices and feasting, they lay down in the temple and fell asleep, never to awaken. The Argive people made and dedicated statues of them at Delphi.

Croesus was annoyed that Solon considered common men to be happier than himself. Solon said that in an assumed lifespan of 70 years, a person has 26,250 days, none of which are the same as the last, and each may bring with them fortune or misfortune. The only way to determine if a person’s life is happy is if their life ends well. Until then, the best that can be said is that they are lucky. Croesus didn’t like Solon’s response and sent him away.

Portents and Prophecies

After Solon left, Croesus had a dream that his favored son, Atys, would be killed by an iron spear. Fearing that the dream was a vision of the future, Croesus quickly had his son marry and hid away all the javelins and spears from the men’s apartments. After Atys’ marriage, Adrastus, son of the Phrygian king Gordias, having been exiled by his father, came to Croesus seeking purification for the accidental killing of his brother. Croesus pitied the man and obliged him, allowing him to remain in Sardis as a guest.

Around this time, Croesus was told that a monstrous boar, reminiscent of Heracles’ fourth labor, had come down from the mountains to ravage the Mysian fields. Messengers asked Croesus to send his son and some men to slay the boar. Croesus agreed to help but refused to send Atys, using the recent wedding as a pretense. However Atys heard of the messengers’ request and questioned his father. Croesus told him of his dream and assured his son that it was not due to a fault in his character that he wasn’t sending him but because he wanted to protect him. Atys reassured his father that if the dream said he would die by an iron spear then hunting a boar should pose no threat. Seeing the logic in this, Croesus changed his mind and allowed Atys to go hunt the boar.

“You say that the dream told you that I should be killed by a spear of iron? But has a boar hands? Has it that iron spear which you dread? Had the dream said I should be killed by a tusk or some other thing proper to a boar, you would be right in acting as you act; but no, it was to be by a spear. Therefore, since it is not against men that we are to fight, let me go.” (Histories, 1.39.2)

Croesus then summoned Adrastus and asked him to accompany his son and to protect him from any harm that might befall him. Atys, Adrastus, and a group of young men went to Mysia and found the boar that was terrorizing the population. They surrounded the animal and hurled their spears at it. But Adrastus’ spear missed the boar and struck Atys, killing him and realizing Croesus’ prophetic dream.

Croesus was distraught at the loss of his son but didn’t blame Adrastus for his death, despite the Phrygian prince being the instrument of it. Instead, he blamed the god who had sent him the dream. Croesus buried his son, and Adrastus, who was wracked with guilt at having killed the son of the man who purified and hosted him when he was at his lowest, committed suicide by Atys’ grave.

Testing the Oracles

For two years, Croesus mourned his son but was shaken from it by the growing power of Persia. He wanted to prevent them from becoming too powerful, so he decided to ask an oracle whether he should attack Persia. However, he first needed to know which of the many oracles could be trusted. He sent out messengers to the oracles in Greece and Egypt, telling the messengers to count one hundred days from their departure and to ask the oracles what Croesus was doing on the hundredth day. Only the oracle at Delphi divined the correct answer.

“I know the number of the grains of sand and the extent of the sea,

And understand the mute and hear the voiceless.

The smell has come to my senses of a strong-shelled tortoise

Boiling in a cauldron together with a lamb’s flesh,

Under which is bronze and over which is bronze.” (Histories, 1.47.3)

Croesus had cut up a lamb and a tortoise and then boiled them in a bronze cauldron with a bronze lid. Satisfied that the Delphic oracle spoke the truth, he made large sacrifices to Apollo in order to win the god’s favor and sent lavish offerings to the temple. He then asked the Oracle whether he should send an army against Persia. The oracle’s reply became one of the best-known prophecies from antiquity. It demonstrated the ambiguous nature of prophecy. In the original Greek, as related by Herodotus, she said,

“ἢν στρατεύηται ἐπὶ Πέρσας, μεγάλην ἀρχὴν μιν καταλύσειν” (Histories, 1.53.3)

If [Croesus] should send an army against Persia, he will destroy a great kingdom.

Croesus was pleased at this response, believing that he would conquer Persia. Yet he was still skeptical and asked the oracle one more question to confirm his interpretation. He asked how long he would rule Lydia. The oracle replied that he would rule until the Persians had a mule as king. Croesus was ecstatic. A mule could never become a king, so his victory was all but assured.

The Fall of Sardis

Croesus marshaled his army and crossed the Halys River into Scythia. He razed farms and attacked the city of Pteria, enslaving its citizens. The king of Persia, who would later become known as Cyrus the Great, raised his own army to oppose Croesus, and the two armies clashed. The fighting lasted until nightfall, with neither side gaining the upper hand. The next day Cyrus didn’t attack, so Croesus took the opportunity to return to Sardis with the intention of summoning allies to aid in his conquest. When he arrived back in Sardis, Croesus dismissed the mercenaries in his army, then sent messengers to the Spartans, Egyptians, and Babylonians to assemble at Sardis in five months’ time when winter was over.

However, against all expectations, Cyrus marched his army into Lydia. Croesus arrayed what was left of his army in the plains before Sardis to defend his capital. The Lydian cavalry charged the Persian army, but Cyrus had sent up all his camels to screen his infantry, knowing that horses couldn’t stand the sight or smell of the animals. The cavalry’s horses turned and fled, forcing the riders to jump off their mounts and fight on foot. The Lydians fought desperately but were ultimately routed and driven back behind the city walls.

The Persian army besieged the city of Sardis for 14 days, probing its defenses for weaknesses. They found one side of the acropolis that was undefended, the hill being so steep that the Lydians assumed it was impossible to assault. One of Cyrus’ soldiers noticed a Lydian descend from this spot, chasing after a dropped helmet and then climbing back up. The Persians ascended from this side, entered the city, and sacked it. Croesus was taken prisoner and brought before Cyrus. The Persian king ordered Croesus chained and placed atop a funeral pyre to be burned alive.

The Fate of Croesus

As the oracle of Delphi predicted, by marching an army against Persia, Croesus destroyed a great empire, it just happened to be his own. As the pyre on which he stood was being lit, Croesus recalled Solon’s words that a person can’t be considered happy until the end of their life is known. Croesus told Cyrus of his conversation with the Athenian and that he had learned the lesson too late. The Persian king considered his words and decided to offer him mercy. He told his men to douse the fire, but the flames were too strong. Croesus prayed to Apollo to save him from his fate. From a clear sky, clouds formed, and rain fell to douse the flames. From then on, Croesus became one of Cyrus’ advisors.

In his lifetime, Croesus ascended to the throne of one of the most powerful kingdoms of the ancient world, expanding its borders and amassing such riches that his name is still synonymous with wealth even 2,500 years after his death. Yet he suffered from the fatal flaw of hubris, an excessive arrogance that made him believe that he could control fate.

He blamed his defeat at the hands of the Persians on Apollo, believing that the oracular god had betrayed him and pushed him into attacking a more powerful enemy. He inquired again with the oracle at Delphi, chastising the god for lying to him and being ungrateful for all the gifts he had given. But the oracle replied that the fault lay with Croesus for misinterpreting the meaning of the god’s prophecies. He didn’t consider that the great empire that would be destroyed could be his own, nor did he understand the meaning of the mule becoming king of Persia. Being born of two peoples, a Medean princess and a Persian subject, Cyrus was the prophesied mule. And so the oracle had told Croesus all that would transpire, but Croesus, in his certainty that his understanding was on the same level as a god’s, sealed his own fate.