In many ways, Leonardo da Vinci was the ultimate Renaissance Man. He was incredibly well respected as an artist, as well as an inventor and an engineer, becoming an exemplar of the era that signaled the rebirth of a continent.

Because of these abilities, Da Vinci and his skills were in great demand by the powerful families and factions of the Renaissance, who jostled for power within Italy’s complex political scene.

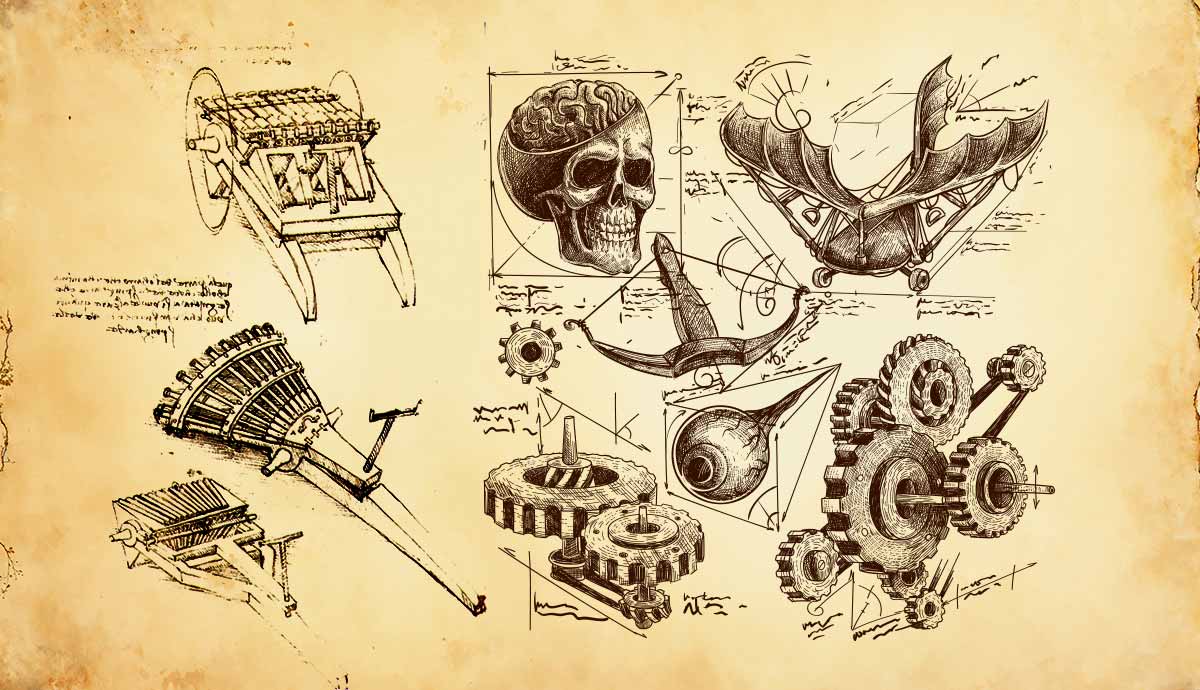

As an engineer and inventor, Da Vinci filled many notebooks with designs and blueprints for complicated machines and devices that would have been fantastical for the era but are seen today as evidence of a mind far ahead of its time. From war to flight, to civil engineering, and beyond, some of these inventions were built, and some remained on paper.

Da Vinci’s Foundation for Invention

Leonardo da Vinci was a man of wide knowledge and learning. Although most famous for his art, he is well known for his technical abilities and for his intricate study of many things around him, from anatomy to flight dynamics, mathematics, geometry, optics, geology, and art theory, among others. He was constantly intrigued by the world and how it worked. In this, his learning process was as important as the final product it helped produce.

In his codices, he recorded what he learned and discovered in minute and meticulous detail. It has been suggested that he deliberately introduced mistakes and wrote in a right-to-left script to make his technical information extremely difficult to decipher, although the latter may be attributed to his left-handedness.

Nevertheless, secrecy was especially important for his contracted engineering or military work, in which his designs had to remain closely guarded.

Da Vinci’s Modern Arsenal

Among Da Vinci’s designs was a blueprint for an armored vehicle similar in concept to the modern tank, which appeared on the battlefields of Europe many centuries later. While under the patronage of Ludovico Sforza, Da Vinci designed the machine to be an enclosed platform that echoed the biological construction of a turtle (or tortoise). With sloped armor to deflect enemy attacks, the vehicle was intended to be built out of wood and covered in metal plates.

The blueprint also featured a mistake—a reversed hand crank, possibly intentional—to deter would-be thieves from succeeding with his design. It was more than 500 years later, however, when the engineers and craftsmen finally realized the invention and constructed it (fixing the “mistake” in the process). It was presented in the 2009 documentary “Da Vinci’s Machines.”

Slow and unwieldy, it could only move on flat ground, but in the right circumstances, it could potentially have been an extremely effective and deadly weapon on the battlefields of Renaissance Europe.

Another notable invention was the repeating organ gun, a precursor to the machine gun concept in providing rapid fire. Da Vinci’s version featured 3 rows, each with 11 barrels, connected to a single revolving platform. The idea was that while one row was fired, the other two rows could be reloaded and readied for firing, thus sustaining a continuous stream of cannon fire. While non-revolving versions of the gun (ribauldequins) had been used since 1339, Da Vinci’s improvements were an attempt to solve the slow reload time, and represented part of a dynamic that would eventually produce the machine guns that ripped apart the battlefields of the 20th century. Like so many of his designs, however, Da Vinci’s organ gun was never built.

Relying on more traditional methods of ballistics, Da Vinci also pursued the idea of crossbows, sketching designs for a rapid-firing, handheld crossbow, as well as a giant crossbow with 80-foot limbs! He applied the geometrical mathematics of the laws of motion to his designs, improving power and accuracy. The Giant Crossbow was designed for pragmatic siegecraft and to intimidate the enemy. Neither of these designs was built in Leonardo’s lifetime, but they were built and tested successfully centuries later. The Rapid Fire Crossbow was built in 2013, with a full working model being released in 2015, while a full-scale working model of the Giant Crossbow was built for the ITN documentary Leonardo’s Dream Machines, which was aired in 2003.

Sogno di Volare: The Dream of Flight

One of Leonardo da Vinci’s most famous avenues of thought was his desire to build a flying machine. He imagined several such vehicles, including the ornithopter, a creation that mimicked birds and bats and their flapping wings to gain flight. The full design was never built (although Da Vinci might have built smaller models), and had it been, the weight-to-muscle ratio and the lack of a powerful enough engine would have made it unfeasible. Manned flight with ornithopters was achieved only in the latter half of the 20th century and remains a deeply challenging endeavor.

Another well-known attempt at flight was the “aerial screw,” which has been attributed as being the first design for a functioning helicopter. As such, Da Vinci is often credited (erroneously) as having invented the helicopter. His Aerial Screw did, however, implement the same principle of lift. The design features a round platform from which a pole holds a spiraling linen sail, which is supposed to be rotated by a crew standing on the platform.

Unlike in modern helicopters, there was no secondary screw (or rotor) to stabilize the platform, so it, too, would have spun wildly. In Da Vinci’s time, there also wasn’t an engine powerful enough to drive the screw fast enough so it would achieve lift. The device, however, was a testament to Da Vinci’s inventiveness and understanding of physics.

While the invention of the modern parachute and its first public test in 1783 were the result of work by Louis-Sébastien Lenormand, his ideas drew on many centuries of theoretical interrogation, including ideas from Da Vinci’s Codex Atlanticus. Da Vinci’s version was canvas in a pyramidal design, supported by a wooden frame. It was finally built and tested in 2000 by daredevil Adrian Nicholas, who commented that the parachute offered a smoother ride than modern alternatives!

From Blueprints to Physical Realizations

Da Vinci’s genius was apparent in many of his engineering designs regarding rivers and bridges. One such example was a portable self-supporting (reciprocal frame) bridge made from pre-cut wooden poles, which could be quickly assembled and disassembled. It was designed so all the pieces could fit together without needing nails, screws, or any other fastening devices. Each log interlocked and supported the structure. It is possible the design was implemented in military campaigns, but the definite truth is unknown.

What is known for certain is that the vast majority of Da Vinci’s inventions remained in the sketch and blueprint stage during his lifetime. There were, however, a few that are known to have been built and applied.

From an engineering perspective, Da Vinci’s work was extremely practical in the context of canals and associated hydraulic systems, and this is where his genius was translated from sketches into physical materials. In 1482, he became the ducal engineer of Milan and designed improvements to the miter lock gates of the Naviglio Grande, translating vague concepts of angled gates into a flawless, working technology. The most famous example still exists in San Marco.

A smaller, but no less incredible invention was the automated bobbin-winder, which had a significant impact on the textile industry. It featured a crankshaft and a connecting rod that moved the bobbin back and forth in a continuous motion, ensuring that the thread was wound evenly around the bobbin. Manually winding thread was slow and uneven, creating a bottleneck in the industry. The concept behind Da Vinci’s invention solved these problems and became a foundational aspect of later automated winding machines.

One of Da Vinci’s most fantastical inventions was a fully-articulated automaton known as the “Mechanical Knight.” His writings suggest he built the Mechanical Knight around 1495 for the amusement of his patron, Ludovico Sforza. It consisted of a suit of armor, inside which was a system of pulleys that controlled the movement of the armor, giving it lifelike qualities. It had a flexible neck, and its arms could move about in various directions, even performing full-arm grasping. According to eyewitness accounts, this wasn’t Da Vinci’s first foray into automata. Before he built the Mechanical Knight, he built a Mechanical Lion, which could move without direct human control. This invention was so awe-inspiring that it was presented by Giuliano de’ Medici as a gift to King Francois I of France upon the monarch’s arrival in Lyon.

Some of Da Vinci’s inventions were completely original, and others were improvements on previous ideas. And while the vast majority of them were never built in his lifetime, what they represent is the man’s ingenuity and vision. His brilliance is still recognized today, and it continues to generate a great deal of respect for the artist, the pioneer, and the dreamer who was Leonardo di ser Piero da Vinci.