Why do we believe in the existence of the external world? This sounds like one of those questions which non-philosophers use to chastise philosophers for asking irritating or irrelevant questions. Of course, there is! It’s common sense, isn’t it? Well, for one thing, it might be worth noting that in certain intellectual and spiritual traditions, it is common sense that we do not have separate existing bodies and that the external world is unreal.

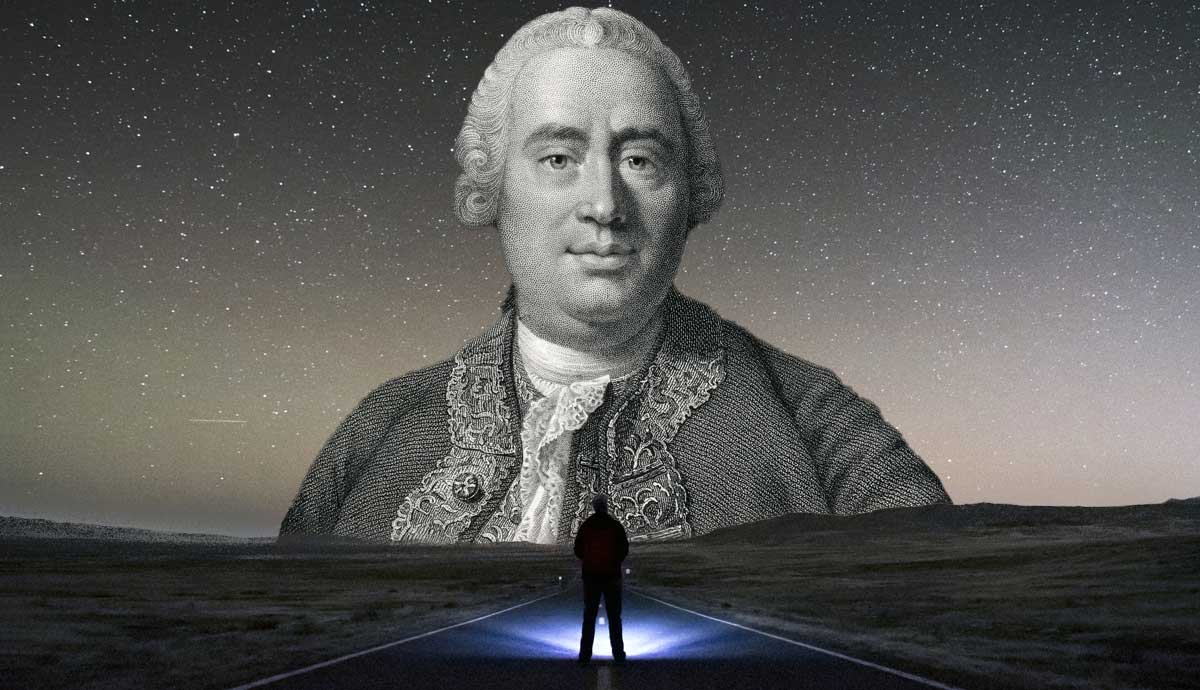

Leaving that aside, David Hume was aware that most of the people he knew would respond to such a question with incredulity and not-a-little scorn, and it was this response that he was interested in. Whereas other philosophers would focus their inquiry on whether or not we have bodies (and, therefore, whether or not there is such a thing as a world outside of those bodies), Hume was much more interested in why we believe that we have bodies.

David Hume’s Queston: Why Do We Believe in Bodies?

The question of the existence of bodies (these are simply external objects we’re talking about, rather than human bodies or any other special category of body) is intimately bound up in the question of the existence of the external world, insofar as the existence of the body as a distinct entity implies the existence of an external world outside of ourselves.

Hume is concerned only with why we have this belief, not with its truth. He claims that we cannot help but hold this belief, and therefore to ask whether it is true is to ask an idle question. It’s not obvious what Hume means when he says we ‘cannot help’ but hold this belief. Is it that it goes beyond the limits of our conception to conceive of the non-existence of bodies whatsoever, or is there a softer sense in which we cannot practically hold this belief – in the course of life, it is inevitable to assume the existence of the body? In any case, Hume is interested in the question: “What causes induce us to believe in the existence of body?”

We should note here that the extension of the logic of the cause, and the attempt to distinguish casual laws, is being applied in the realm of human belief. The philosopher Gilles Deleuze once credited Hume for laicizing belief (meaning, to apply it for non-religious purposes) – at various points, what that really means is that Hume naturalized it.

Hume sees certain beliefs, including this one, as natural enough to be the proper subject of an inquiry into human nature and as an element of the science of man. He also claims that this is “an affair of too great importance to be trusted to our uncertain reasonings and speculations.” This stated position of neutrality in the Treatise of Human Nature, Hume’s first major philosophical work, becomes a position of silent disregard in the Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, his more mature work. Hume takes our beliefs in the existence of bodies to be natural, but he also takes the assumption of a philosophical approach to them to be natural.

Philosophical inquiry cannot help but draw a wholly skeptical conclusion for Hume, and therefore both belief and disbelief in the existence of bodies are, in different respects, natural on Hume’s account. In answer to the question posed previously, we are inclined to think of the sense in which we “cannot conceive of the non-existence of the body” as a softer kind of inconceivability, a practical impossibility. Clearly, philosophical reasoning can lead us to believe something else.

Continued Existence and Distinct Existence

The crux of our belief in the outer world and in objects has two elements – that of the continued existence of bodies and that of their distinct existence. We believe both that things continue to exist when no one or nothing is perceiving them, and we believe that their existence is entirely independent of their being perceived at all.

There are three sources of belief for Hume: our senses, our powers of reasoning, and our imagination. Clearly, the senses cannot be the source of this belief, given it is a belief about the existence of the world when it is not being perceived. Moreover, as Hume points out, “properly speaking, ‘tis not our body we perceive, when we regard our limbs and members, but certain impressions, which enter by the senses; so that the ascribing a real and corporeal existence to these impressions, or to their objects, is an act of the mind as difficult to explain, as that which we examine at present.”

Some of the perceptions which we have of things seem to be hard to separate from those things being perceived – the various pains, pleasures, and so on which we might associate with any given object (a knife feels sharp, a pillow feels soft, and so on).

Reason can’t be relied on either, both because ordinary people manage to believe in the existence of bodies without undertaking any process of reasoning, and because there is no way to reason from the perceptions we have to the existence of bodies – only perceptions are ever evident in the mind, and so we could never demonstrate a constant conjunction between these perceptions and some others existing downstream from them.

So we are left with only one option – our belief in the existence of bodies and of the external world must arise in the imagination. Hume nonetheless thinks that we should be able to identify those perceptions which interact with the imagination, which encourage it to accept the existence of bodies and the external world. Hume identifies two features of perception that might do just that, features he calls “constancy” and “coherence.”

Constancy, for Hume, involves the absence of change, the tendency of recurrence in our perception of things and in our perception of the relation of things: “Those mountains, and houses, and trees, which lie at present under my eye, have always appear’d to me in the same order; and when I lose sight of them by shutting my eyes or turning my head, I soon after find them return upon me without the least alteration. My bed and table, my books and papers, present themselves in the same uniform manner, and change not upon account of any interruption in my seeing or perceiving them”.

Constancy and Change

Constancy is not absolute – evidently, things can change to some extent. When things do change, so Hume claims, we find that they change in a way that is nonetheless coherent:

“When I return to my chamber after an hour’s absence, I find not my fire in the same situation, in which I left it: But then I am accustom’d in other instances to see a like alteration produc’d in a like time, whether I am present or absent, near or remote. This coherence, therefore, in their changes is one of the characteristics of external objects, as well as their constancy.”

There are a couple of things to note here. Hume seems to think that we are able to perceive that objects are (in themselves) constant or coherent, but we should be strict in distinguishing our perception of constancy and coherence from any fact about actual objects. Taking that thought a step further, Hume argues that very often, we find ourselves in two minds concerning the constancy and coherence of perception. If we appear to perceive the same thing unchangingly apart from some brief interruption, or at least an interruption that is regular and predictable, we are inclined to consider the objects on either side of an interruption as distinct but similar rather than perfectly identical. Yet, Hume holds that through an act of the mind, we transform this set of perceptions into the belief that we have perceived some distinct object. However, as Barry Stroud points out, this clearly presupposes some concept of the “distinct object,” along with other associated concepts (“perfect identity,” for example).

David Hume on the Atomism of Perception and Imagination

All of this goes to show that the very structure of perception for Hume is inadequate for this task – perceptions, for Hume, are themselves atomistic and momentary. No perception is sufficiently extended in time. Rather, the belief in the constancy of external objects arises as a “fiction of the imagination:” because “the passage from one moment to another is scarce felt,” our imagination generates the idea of a consistently existing object.

One might still reply, as Stroud does, that our imagination could only respond to this fact if we had some idea of identity, or of the constantly existing object, already inscribed. Hume’s response is that the generation of this concept is a direct response to the apparent contradiction between the constancy and consistency of our perceptions, and the various interruptions and changes to them. Hume claims that we must sacrifice one principle to the other, but really there is a more horizontal integration to be had by positing the existence of separately existing objects, and characterizing interruptions to our perception of such objects as a fact of our perception rather than a fact about the objects themselves. So for Hume, the idea of belief in bodies is a fiction of the imagination, which is necessary to reconcile two elements of our perceptions – their resemblance and their interruption.