The seventeenth century was a turbulent time for Europe with many long wars, religious division, economic conflict, a mini-ice age, poor harvest, plague and pestilence. A perhaps understandable effort was made to understand why people were blighted by such evil times, and across the continent one answer could often be found – witchcraft. Through the late medieval and early modern period – the mid fifteenth to seventeenth centuries – there were perhaps 35,000 people convicted and executed for witchcraft in Europe. Most of them – perhaps 70-75% of them – were women, and for most of Europe the investigation could (and often did) involve torture, and execution was by burning.

Witchcraft Prosecutions in Britain

Whilst there were around 35,000 convicted witches in Europe, in Britain the numbers were much more modest. There were around 500 people convicted in England, somewhere between 3-4,000 in Scotland – and just five in Wales. With that said, it was commonly accepted that magic was real, and that unseen (and often undetectable) creatures were all around – from fair folk to angels to ghosts to imps. After all, when things you cannot see have an effect you can there must be a reason. And if they exist then people who could interact with them could have great power.

Before the 1540s there weren’t even laws specifically outlawing witchcraft (the first in England was during the reign of Henry VIII, whilst in Scotland it was James VI); in part this was because if a crime was committed with magic then it could simply be investigated as such, and in part because the Inquisitions of the Catholic Church hadn’t ever really gotten a foothold in the British isles.

The British Witch Hunt Craze

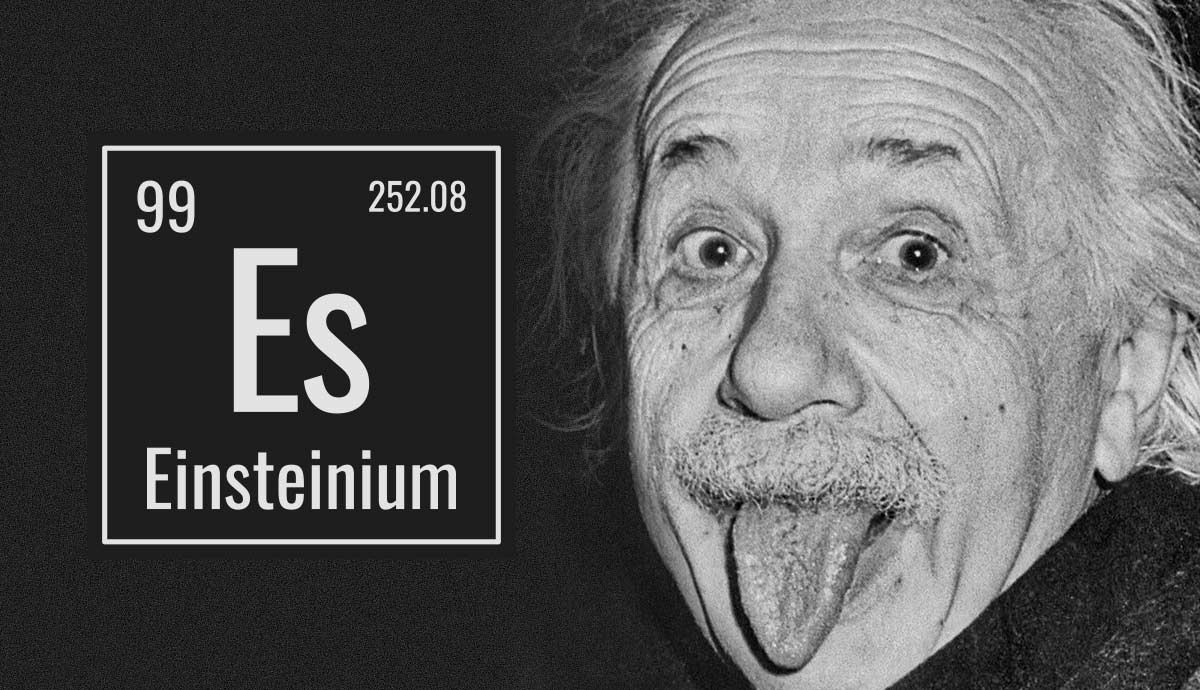

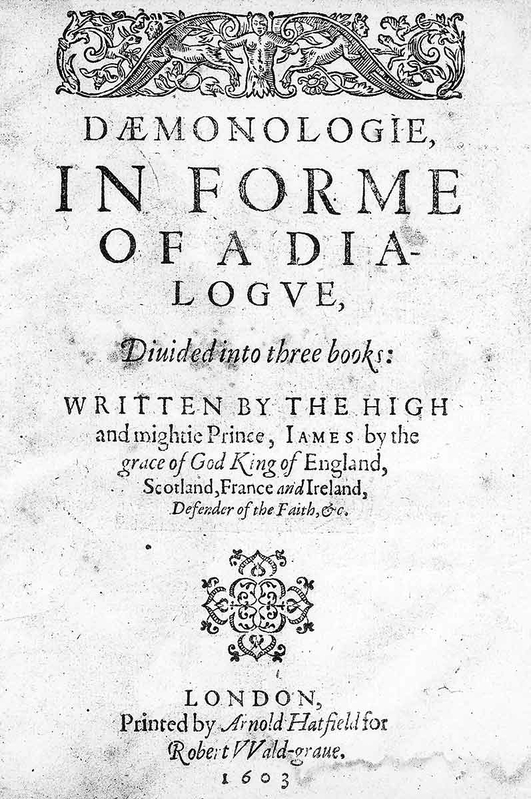

Heinrich Kramer’s Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches) was published in 1486 and was a foundational text for would-be witch hunters. In Britain it was replaced in the late sixteenth century by the book Dæmonologie. This was written by the Scottish king, James VI. King James had been interested in witchcraft since his visit to Denmark sparked fears of witchcraft being used against him, and his book Daemonologie became a key text for witchfinders in Britain and Ireland, along with essential reading for godly folks concerned about the spread of heresy and devil-worship.

James VI and I passed a new law on witchcraft; no longer was it necessary to have proof that magic was used to cause harm or death to people or livestock, evidence of a covenant or pact with the devil in the flesh, in dreams, or through the use of familiar spirits was sufficient. And a confession was considered compelling evidence indeed. Both Elizabethan and Jacobean acts had also made witchcraft in England expressly a civil rather than religious crime.

The Most Famous English Witch Finder

There were relatively few prosecutions for witchcraft in England before the civil wars of the 1640s, with the notable exception of the 1612 Pendle Witch Trials (in which twelve people were accused of witchcraft; ten were found guilty and hanged, one was found not guilty and released, and one died whilst in prison). This might be because England was generally peaceful and prosperous, especially compared with the continent, or perhaps because it was a civil rather than religious crime – or because the growing number of radical Protestants first concerned themselves with Catholics.

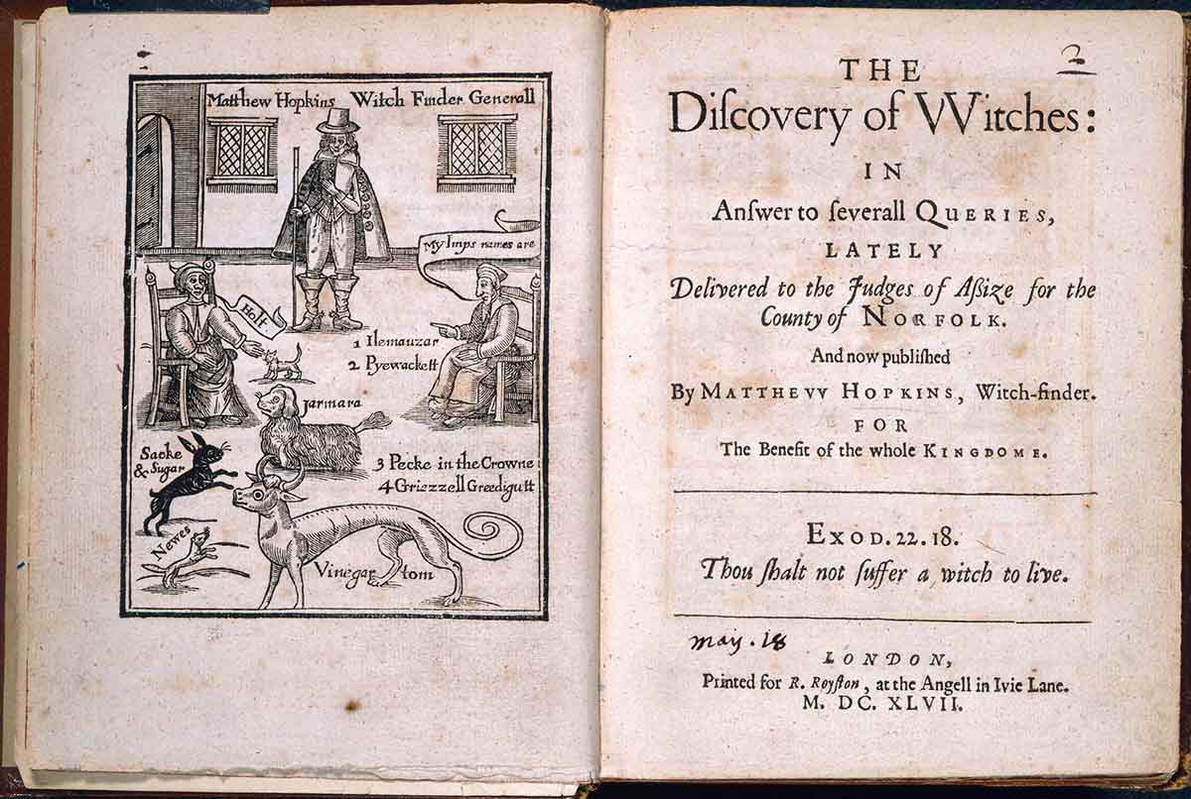

It was not until the British Civil Wars, and notably the period after 1644, that the hardships and loses caused by the conflict (along with poor harvests) set the conditions for an English witch panic. The best known of the people who sought to uncover a devilish origin for the people’s misery was Matthew Hopkins.

Hopkins was educated, ambitious, was the son of a radical independent clergyman (what today would be called a Puritan minister) who claimed the title of ‘Witchfinder General’. With his associate John Stearne, Hopkins was ruthless in ridding East Anglia (primarily the counties of Suffolk, Essex, Norfolk, Cambridgeshire, and Huntingdonshire) of witches. Between the two men were responsible for the investigation, prosecution, conviction, and execution of at least 114 people – more people than had been hanged in the 160 years before they took up the role.

How Witches Were Identified

In England it required the permission of the monarch for people to be subjected to torture – which was the common way to force a confession from an accused witch (after all, the devil would prevent them from speaking truth without it). As such Hopkins and Stearne could not torture the people they accused of witchcraft. Despite this, the majority of people they did charge as witches did confess, and often accused others in turn. There were a couple of techniques which they, and other English witch hunters, relied upon.

Firstly, and most importantly, a familiar spirit would need to feed on the blood of their mistress (or, occasionally, master). As such a suspect would be ‘searched’ for a witch’s mark or devil’s mark (often after all body hair had been shaved) – this was a spot or blemish, such as a wart, birthmark, age spot or similar. If one could not be found then they might be subjected to ‘pricking’, where likely spots (often the arm) might be cut with a knife or pricked with a needle – Stearne was renowned for his skill with a needle (sometimes said to be retractable). When no pain was felt, or blood drawn, this would be proof of an unseen mark – the wound on the soul rather than the body. Needless to say, the odds of uncovering this evidence were high.

Accused witches might be ‘swam’, often drawn across a body of water by ropes attached to fingers and toes, or by binding the accused to a chair. If they floated, they were rejected by the water (as they had rejected the water of baptism) and were thus guilty. Hopkins had been warned about this, and usually required his victims to given permission – for surely an innocent would seek to provide proof of their innocence…regardless it was more a public spectacle than anything ever presented as evidence in court. A court whose jury was doubtless made up of people who had witnessed the test.

Most common of all, however, was the simple act of ‘watching’. Though benign sounding, the accused would be sat upon a stool and closely observed so that their familiar bringing word to or from the devil would be seen, and their feeding on the blood of their mistress likewise. They would also be spoken with, though some might say interrogated or harangued, censured lest they made a confession. As they would be being observed they were denied food or drink, and if sleep threatened would be stood up and made to walk back and forth. It is said that Hopkin’s first victim confessed after four days to having five familiars.

How Witches Were Punished

Whilst in Europe (and in Scotland) convicted witches who were executed (and not all were, though most suffered that fate) were generally burned – sometimes being strangled or beheaded first – this was not the case in England and Wales. Because witchcraft was a civil offense they would be executed in the normal way, according to custom.

That is to say, commoners would be hanged – a process which could be as fast as a broken neck, or as slow as gradual suffocation – whilst nobility might be beheaded (which might take several blows from an axe). In some cases, those of petty treason (normally a woman who used witchcraft to kill her husband) a very few convicted witches were burned, this was because the crime they had used witchcraft for was a heresy, not because of the witchcraft itself. The same is true of witchcraft prosecutions in the USA, most famous of which was the Salem Witch Trials.

An End to Witch Trials in England

The last witch trials in England took place in the early 18th centuries, and the Witchcraft Act of 1735, which made it a crime of fraud to claim to have magical powers or to accuse someone of being a witch. The last person to be convicted under that act was Helen Duncan, a medium and spiritualist who was jailed in 1943 who came to the attention of the authorities after apparently contacting the spirits of a sailor whose ship’s sinking was being kept secret.