Europe has been in a constant state of conflict and disarray since its first states began to form. These conflicts have all required negotiations and the signing of peace treaties. These were laborious and intense processes that required years of debate between the great powers of Europe. When completed, each of the following European treaties would drastically reshape the outlook of the continent and initiate the ascendancy of a new dominant power over the continent.

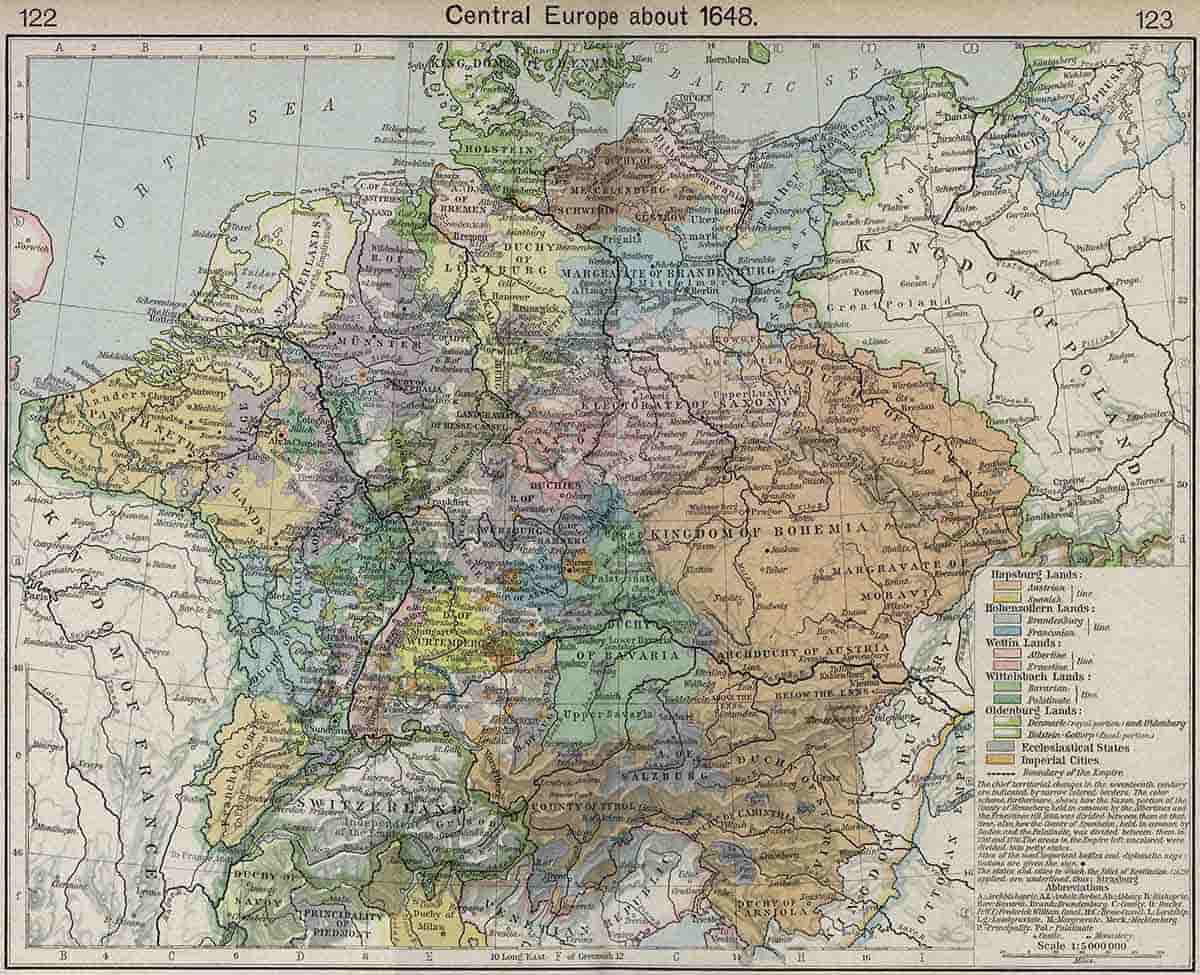

1. The Peace of Westphalia (1648) as a Key European Treaty

As one of the first examples of large-scale multi-nation diplomacy, the two European treaties that made up the Peace of Westphalia signified the end of the Thirty Years’ War.

Within the context of the advent of Protestantism, the Thirty Years’ War was primarily a religious civil war within the Holy Roman Empire (HRE) which gradually expanded into a struggle for dominance over Europe. The Peace of Prague (1635) ended the religious aspect of the conflict and united most of the HRE, allying with the Habsburg dynasty of Spain against the Bourbon dynasty of France, backed by Sweden and the Dutch Republic.

A preliminary peace agreement was signed in December 1641, allowing the powers to gather to negotiate. The Peace of Westphalia was actually a combination of two peace treaties, one signed at Osnabrück and one in Münster. At the time, Münster was an exclusively Catholic city, which made it an easy spot for Catholic French dignitaries to travel to negotiate with the HRE. Conversely, Protestant Swedish dignitaries chose Osnabrück as it was a mix of Catholics and Lutherans, more likely to avoid religious confrontation.

The 109 delegations that arrived between 1643 and 1647 never met in a single session. The primary focus of the negotiations was the Holy Roman Empire and who would hold power—the Emperor, at the time Ferdinand III, or the Imperial estates themselves.

The product of the treaties increased the influence of the princely states. Three hundred princes gained more sovereignty for themselves, but Ferdinand did maintain central power through the Imperial Diet. An important section of the treaties confirmed the 1555 Peace of Augsburg which guaranteed the right to practice one of the three recognized religions: Catholicism, Lutheranism, and Calvinism. These three groups would receive equal representation in court as well. This was (at least temporarily) a pause in the religious conflict which had engulfed the continent for centuries.

The Peace of Westphalia also resolved some territorial disputes. France solidified and strengthened its borders, gaining territory within Germany. Sweden also gained provinces, a say in the politics of the Holy Roman Empire, and war reparations. Although not part of the Westphalian agreement itself, the Dutch Republic and Swiss Confederation signed separate treaties recognizing their legitimacy as states.

The reception of the peace was mixed. Pope Innocent X rallied against it as it permitted deviation from Catholic doctrine. Although it helped resolve religious tension, particularly within the Holy Roman Empire, and minor disputes between powers, the two treaties did not end the fighting between states. A primary reason for this was the ascension of France. Indeed, the agreements at Westphalia laid the ground for Louis XIV to dominate European politics over the next few decades. Known as the “Sun King,” he would heavily involve France in European wars, particularly with Spain but eventually all of Europe in the Nine Years’ War.

Recently, historians have debated the legacy of the Peace of Westphalia. They challenge the notion that the treaties were an example of international relations and recognizing many of the democratic norms we witness today, like the primacy of borders.

2. Treaty of Paris (1763)

If Westphalia began French dominance over Europe, the Treaty of Paris was the European treaty that led to British dominance over the rest of the world. The agreement was signed to end the Seven Years’ War, which could be considered the first “world” war. The conflict was a combination of the French-Indian War, the Spanish-Portuguese War, the Third Silesian War, and the Anglo-Spanish War.

The war began over a dispute between the British and French over their colonies in North America. Fighting soon expanded across the globe, and the British, Portuguese, and Prussians eventually prevailed.

When it came to negotiating the peace, the negotiators were divided. On one side were Britain and Portugal, who had managed to fend off challenges from the other great powers, Spain and France. Prussia and Austria signed a separate peace treaty, the Treaty of Hubertusburg.

Britain and France gave back what they had conquered throughout the war, except for territories in North America, where Britain asserted its influence, taking much of Canada and Louisiana from the French and Florida from the Spanish. This settlement, however, was criticized by many in Britain, who felt that the peace could have been much more punitive.

The fallout from the Seven Years’ War would assert Britain—and Prussia—as the rising European powers. Britain, in particular, strengthened its grip on North America, India, and eventually Australia. However, perhaps the most significant effect of the Treaty of Paris on Europe’s history did not actually come from the continent itself. The enormous cost of the war meant that Britain now had to demand taxes from its colonies in an attempt to recoup its lost revenue.

Attempts to collect funds for the war angered many colonists, particularly in North America. Just ten years later, they rebelled against the British. After another ten years, many signatories of the first Treaty of Paris would be back to sign another agreement. This time it was to confirm the independence of the United States of America.

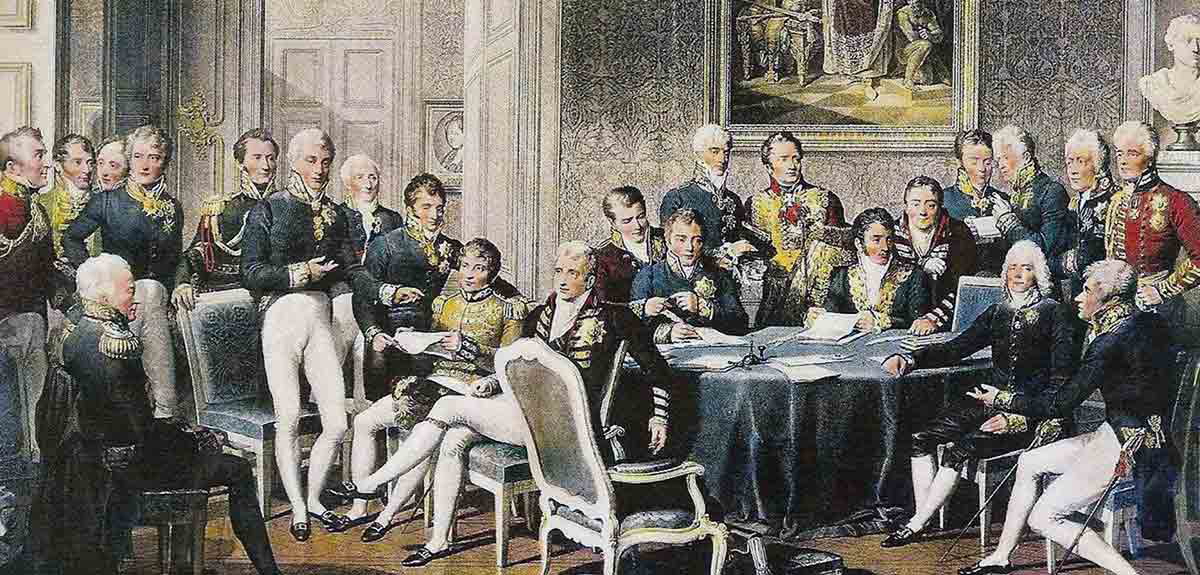

3. Congress of Vienna (1814-1815)

The general peace from the Treaty of Paris lasted only thirty years, and the Napoleonic Wars would soon envelop Europe for two decades, requiring another major European treaty. Unlike in their previous conflict, where Britain and France fought across the globe, most of the fighting was focused in mainland Europe.

Right after their first victory in 1814, the victorious major powers (Britain, Prussia, Austria, and Russia) gathered in Vienna to decide how to deal with the impacts of the French Revolution and Napoleon’s grand rise and fall from power. They would stay negotiating in Vienna for a year, concluding their agreement just before Napoleon surrendered for a second time.

The treaty mainly was a restoration of the land France had conquered, with each of the major kingdoms seizing some land for their own. Britain expanded its colonial holdings, Prussia took Saxony, Austria claimed Northern Italy, and Russia annexed Poland. The Congress also established the German Confederation, of which Prussia and Austria were a part, as a buffer to prevent future French aggressions. The confederation formed the basis of what Otto Bismarck would unite to form Germany in 1870. Another buffer, this time between the German Confederation and France, was established in the Kingdom of the Netherlands.

A standout of the Congress was French Prime Minister Talleyrand. In a hopeless position, at the mercy of the coalition formed against it, Talleyrand managed to play the great powers off each other throughout the negotiations. Initially excluded from proceedings, he included himself in the final settlement, minimizing the damage inflicted upon France.

The biggest victor of the Congress of Vienna was Britain, which emerged poised to dominate the international order. It had eliminated its greatest rival and could now focus on further colonial domination, expanding its reach across the globe.

The legacy of the congress itself is disputed. On the one hand, it is pictured as a conservative backlash against the American and French Revolutions. Democratic and liberal movements were suppressed as the monarchies of Europe reasserted their dominance. Nationalist forces within their empires were also restricted. However, the resulting broad international peace would remain in place for a century, making this arguably the most successful treaty on this list.

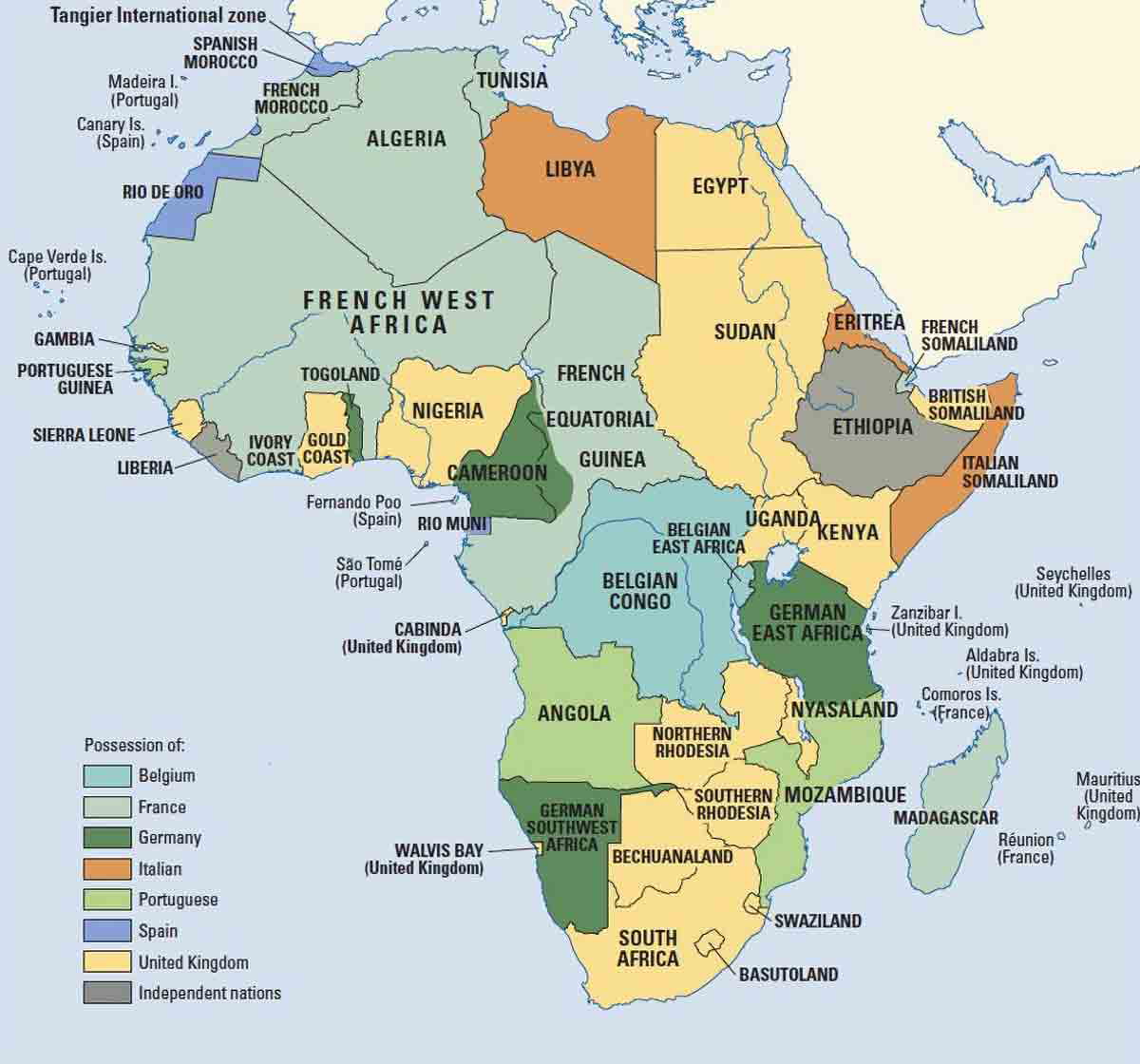

4. Berlin Conference (1884-1885)

As a result of the Congress of Vienna, Europe experienced relative peace throughout the rest of the nineteenth century. Secure in their borders, major powers soon turned their attention back to their colonial holdings and potential avenues for expansion, with all eyes on Africa. The existing colonizing powers gathered in Berlin between 1884 and 1885 to codify the conquest of Africa that would take place over the next 20 years, commonly known as the Scramble for Africa.

The agreement that was finally reached, the General Act of Berlin, had the dual effect of legitimizing previous colonial efforts and indicating how future colonization would take place in Africa. Previously, all major European powers had launched expeditions into the African continent, looking to claim whatever land they could. To avoid another European war, the Berlin Conference laid out the rules for future conquests. All other signatories would be notified if any new African land was claimed, and the process for legitimizing these claims was written into law.

Since this did not wholly prevent crises, a few flashpoints occurred between the major powers. The first was the showdown between the British and the French at Fashoda. The second was the Agadir Crisis, where Germany and France came close to sparking an international conflict. Like many issues regarding African colonies, these were soon resolved by separate treaties between the powers.

The Berlin Conference also succeeded in its goal of legitimizing the conquest of Africa in the eyes of the European public. Faint overtures were made to the supposed humanitarian mission that disguised the true goal of expansion and exploitation, the colonial powers claiming they aimed to eradicate slavery from the continent.

The result on Africa itself would be devastating, the full scope of which is too broad for this article. The worst immediate effect was that it approved Belgian control over the Congo Free State (now Democratic Republic of the Congo). This was a scam run by Leopold II, who would plunder the region for his own gain over the next decade, imposing brutal conditions on the Congolese.

For Europe itself, the Congress would start a hyper-competition between the powers. Rivalry between the colonial states would lead to increased confrontation and brinksmanship across Europe, adding extra tinder to the powder keg that would eventually erupt into World War I.

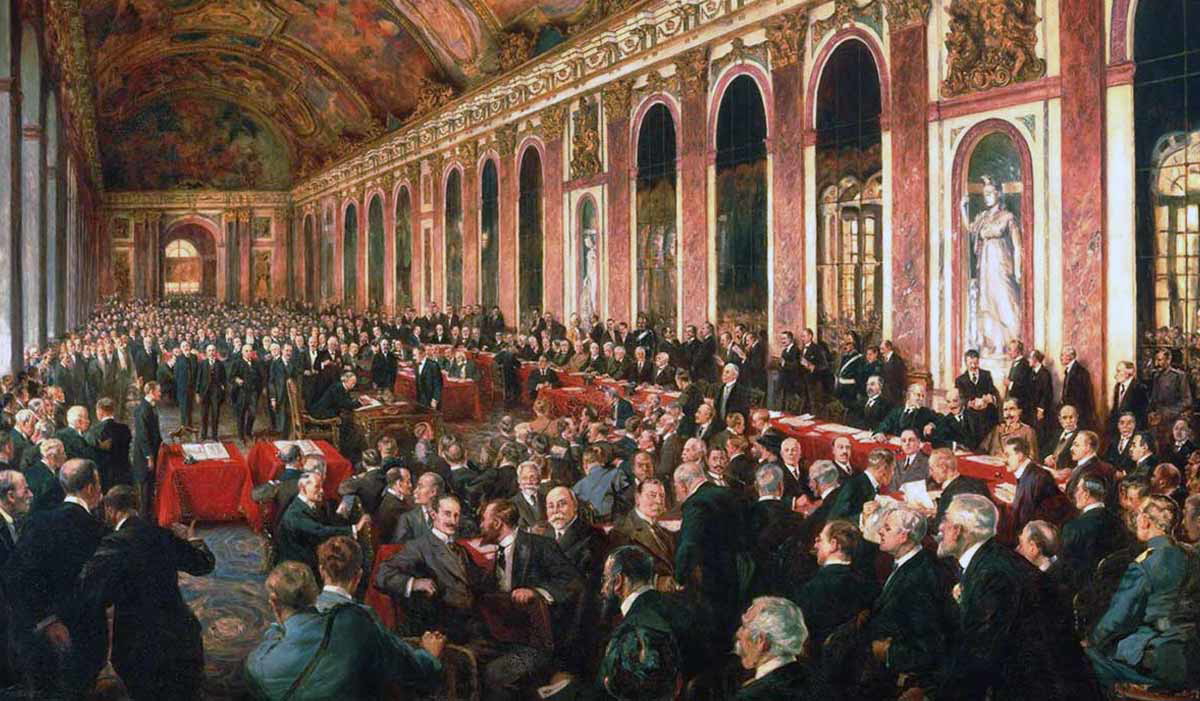

5. The Treaty of Versailles (1919): The European Treaty That Ended WWI

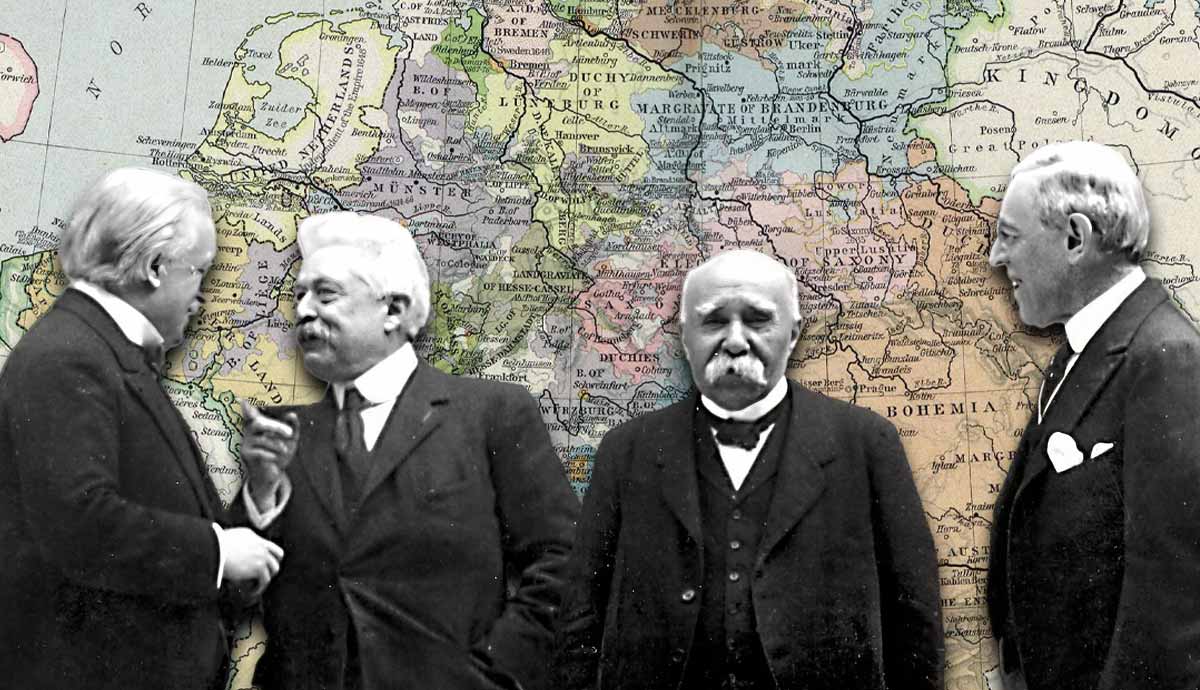

Perhaps the most famous European treaty on this list, the Treaty of Versailles is certainly the most impactful of the 20th century. The agreement was signed exactly five years after the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, which had sparked World War I.

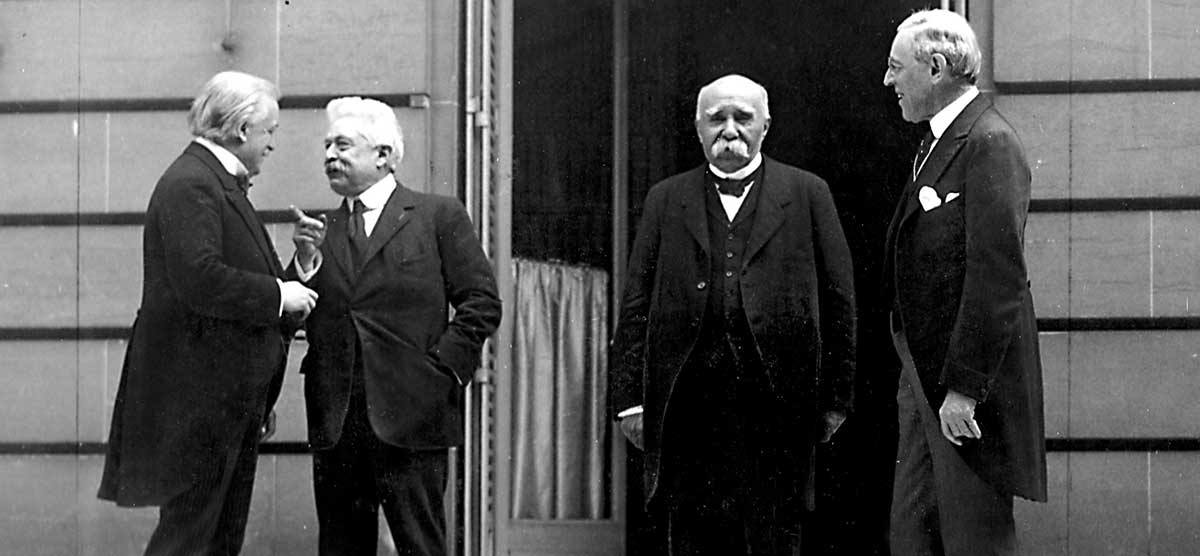

Named after the famous palace of the Bourbon kings, most discussions took place in Paris, with only the signing taking place in the Palace of Versailles. The result was heavily divisive, both for the victorious and defeated powers.

The treaty focused on punishing Germany severely. The “Big Four” dictated terms to the defeated powers excluded from the conference. Germany was forced to disarm, lose its empire, pay heavy reparations, cede some of its European territory, and accept sole responsibility for the war. Similar treatment was given to Austro-Hungary, which saw its empire completely disbanded.

The horrors of war had left all participants looking to create a system that would prevent a similar war from happening again. This system came in the form of the League of Nations, the first real attempt at an international organization devoted to diplomatic mediation.

The Treaty of Versailles also established some brand new states in an effort to promote self-determination: Poland, Yugoslavia, and Czechoslovakia were the most notable. In a cruel twist of fate, these newly created national entities would be the flashpoints of conflict over the next two decades and beyond.

The terms of the treaty themselves would soon lead to the rise of the Nazis and eventually World War II. Although historians endlessly debate whether Versailles is a direct link to Germany’s invasion of Poland, it is undeniable that Adolf Hitler’s rise to power was centered on the systematic overturning of Versailles. He used the “stab in the back” myth to remilitarize the Rhineland, rearm Germany, and unite with Austria, all forbidden by the terms of the treaty.

The impact of the Treaty of Versailles has been the subject of intense scrutiny. Debates focus on whether it was too punitive on Germany and whether it created the issues that would plague the continent, and the world, for the rest of the century.

Honorable Mentions

These are some treaties which were devised by European powers, but didn’t have the direct effect on Europe as a whole, like the five listed above:

- Treaty of Nanjing (1842): Outlined the abuse of China/the Far East by European Powers. Forced China to trade on unequal terms with the great powers, particularly Britain, which exploited China’s population and resources.

- Treaty of Sèvres (1920): Divided up the remnants of the Ottoman Empire—the random division of territories still impacts the region today. The Treaty of Sèvres was never ratified but began the process of dissolving the Ottoman Empire that was codified in the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. Britain and France would gain much of the Ottoman territory which they quickly abandoned following the Second World War.

- Treaty of Verdun (843): Divided the Carolingian Kingdom between the three sons of Louis the Pious and shaped the medieval states that would rise in the following centuries. The three kingdoms that emerged would come to form modern-day France, Germany, and the Low Countries/Switzerland/Italy respectively.

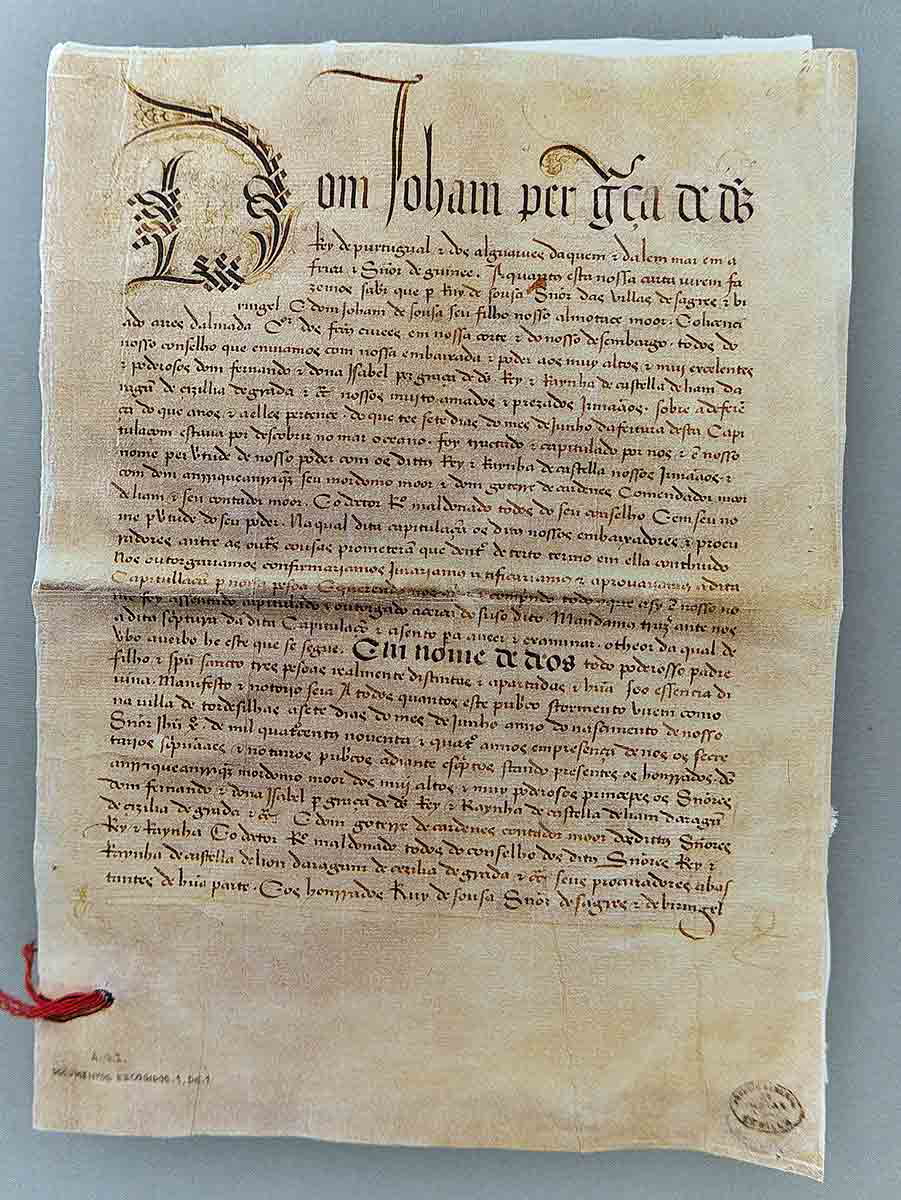

- Treaty of Tordesillas (1494): Divided the colonial world between Spain and Portugal. Portugal would be free to expand its lucrative colony of Brazil and small trading ports in the Indian Ocean. Spain received the rest of South and Central America.