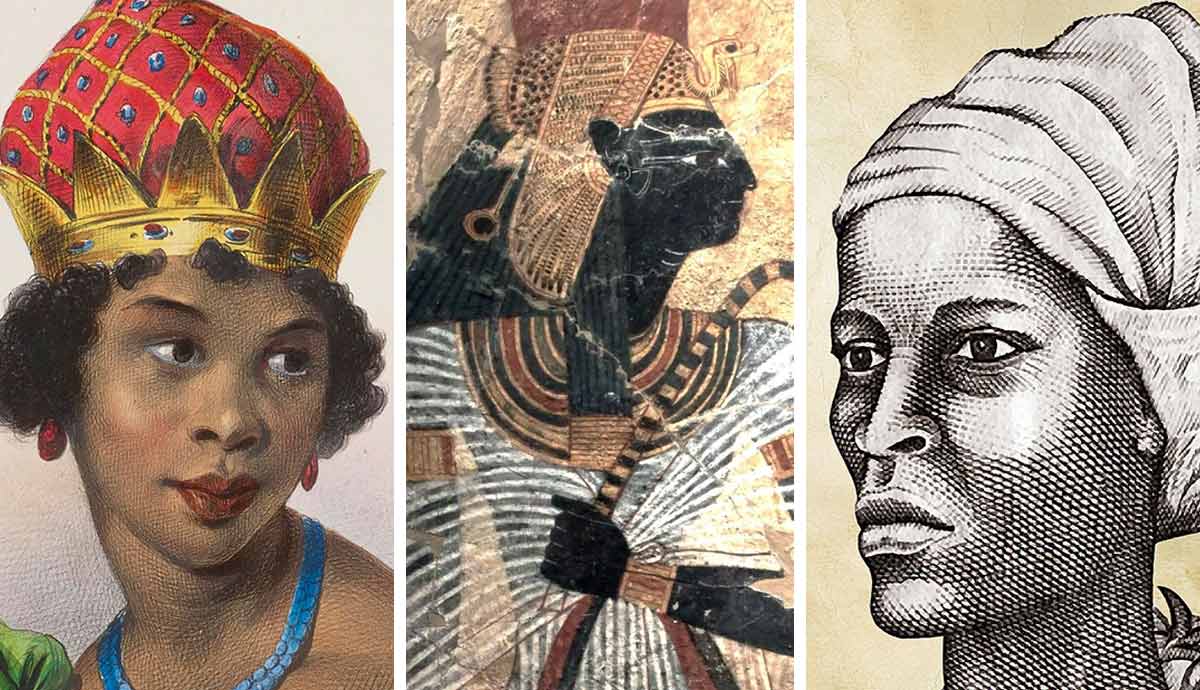

Artemisia I of Caria was the Queen of the Greek city-state of Halicarnassus, but she allied herself with the Achaemenid Empire during the Greco-Persian Wars. She gained notoriety through famous chroniclers such as Herodotus and Polyaenus who made sure her bravery went down in history. Her rise to a position of power in the ancient world was both unlikely and unexpected. Meet the enigmatic warrior queen with seven fascinating facts.

1. She Became Queen as a Regent

Artemisia’s origins are shrouded in mystery. Her father was King Lygdamis of Halicarnassus, and her mother was an unknown woman from Crete, suggesting she was probably a concubine or “pallake,” but she may have been a queen.

King Lygdamis died around 484 BCE, followed by Artemisia’s husband, whose name is not preserved, in 480 BCE. At the time, Artemisia had a young son, Pisindelis, who was too young to rule, so Artemisia assumed the position. Female rulership was rare in classical Greece, and there are few other examples of women assuming the primary position of power in the absence of a king.

Artemisia’s mother’s Cretan culture and her father’s prestigious Anatolian lineage likely provided Artemisia with a varied homelife unlike that of other Greek nobility, particularly for a woman. Contemporary Greek women from elite families received some level of education, although this varied from city-state to city-state.

Halicarnassus was of utmost importance as a centre of commerce between Anatolia and Greece, which presumably exposed the young Artemisia to even more affairs of state. Therefore, while Artemisia was not necessarily born to inherit the crown of a strategic, coastal trading post, her later successes clearly suggest she had some training in political, diplomatic, and military affairs.

2. She Was Greek, But a Persian Ally

Despite Halicarnassus being a primarily Greek settlement in Southern Anatolia, when it came to the Greco-Persian Wars, Artemisia fought for the Persian Achaemenid side. Sitting between Greece and Persia, the province of Caria had a uniquely Greek culture but was conquered by Cyrus the Great around 545 BCE.

Halicarnassus enjoyed far greater autonomy than many other Persian satrapies, likely due to the significance of its economic power and the political influence of its ruling family within both Greece and Anatolia. There is little tangible evidence of any pressure being placed upon the city-state to supply troops to fight in the war. However, we can assume they felt at least somewhat obliged, so as not to fall out of favour with the Achaemenid Empire.

However, there would certainly have been no need for the ruling queen to attend, never mind lead her forces into battle. Consequently, the decision to do so would have been Artemisia’s own.

3. She Advised Xerxes Against the Battle of Salamis

Prior to the infamous Persian defeat in the naval Battle of Salamis, Xerxes assembled all of his military commanders and enquired whether the Achaemenid forces should engage with the Greek city-states at sea. Artemisia had just led her troops in the naval battle of Artemisium, which was fought concurrently with the Battle of Thermopylae. Here, she had proved herself as an expert military strategist and helped secure an upper hand for the Persians.

With the Achaemenid victory at Thermopylae, the Greeks were forced to abandon the battle of Artemisium and fled to the coast at Salamis. Furthermore, many deserted Athens, and the Persians proceeded to sack the city.

Now, Xerxes wanted to continue the momentum and pursue the allied Greeks at Salamis, where their navy was waiting. All of his commanders agreed that this would ensure his victory, except Artemisia. She noted the Greeks’ superiority in naval warfare.

According to Herodotus, the Queen of Halicarnassus described the poor position of the Greeks as they had abandoned their cities and had a limited supply of resources. She suggested that if the Persians moved towards the Peloponnese, they would cut the Greeks off from their most prominent bases, forcing them to abandon the war. Xerxes commended Artemisia for her wise input, but ultimately decided to follow the advice of his other commanders and engaged with the Greeks in the straits at Salamis. This resulted in a crushing defeat for the Achaemenid navy.

4. A Reward of 10,000 Drachma Was Placed on Her Head

During the clash at Salamis, an Athenian ship was in pursuit of Artemisia’s ship. The Queen had to think quickly as she tried to escape. Enclosed by her Persian allies, she ordered that the Persian flag be lowered and had her ship row straight into an allied Calyndian ship, pretending to be one of the Greeks.

As reported by Herodotus, a bounty had been placed on Artemisia because the Greeks found it so abhorrent that a woman could command a vessel against Athens. Ten thousand drachma would be awarded to any man who captured the Queen of Halicarnassus and returned her to Greece alive. This would have been a terrifying prospect to Artemisia. If she were captured, she would likely have been sold into slavery.

Therefore, Artemisia was seemingly prepared to do anything to evade imprisonment. Once she had sunk the Persian ship, the Athenian vessel captained by Ameinias, brother of the famous playwright Aeschylus, gave up on the chase as they assumed the ship was either an ally or a Persian ship that had betrayed the Achaemenid cause. It is assumed by Herodotus that Ameinias did not know Artemisia was on the ship, as capturing the Queen of Halicarnassus would have brought him considerable notoriety and great financial gain.

It is believed that Xerxes was watching the onslaught from the shore, and he and his advisors assumed Artemisia had sunk a Greek ship. This caused Xerxes to utter a now-famous quotation, “My men have become women; and my women, men.” None of the crew of the sunken ship survived, and thus the deception was never made known to Xerxes or any of the Achaemenids during Artemisia’s lifetime.

5. Xerxes Followed Her Advice to Leave Greece

Through her prowess in both the Battle of Artemisium and the Battle of Salamis, as well as her advice as a tactician, Xerxes was thoroughly impressed with Artemisia. In the wake of the Achaemenid defeat at Salamis, Xerxes was sceptical of his advisor and commander, Mardonius, who suggested that the King flee and leave his troops in Greece to fight under him instead.

Therefore, Xerxes asked Artemisia for her advice as she had been right about Salamis, when all his other commanders, including Mardonius, had made the wrong call. On this occasion, Artemisia agreed with Mardonius. She explained that if Mardonius won, it would be under Xerxes’ auspices and still bring him great honor. But if he lost, Xerxes would not be tainted by the defeat. Plus, any Greek victory would only be against Xerxes’ slaves, and not the king himself. Satisfied, Xerxes returned to Persia.

Additionally, Xerxes trusted Artemisia to lead his illegitimate heirs back to Ephesus, a Persian stronghold in Anatolia. As a reward for her services, Xerxes presented Artemisia with a bespoke suit of armor.

6. We Do Not Know Her Fate After the War

After the Greco-Persian War, Artemisia faded from history. Two rumors about her fate persist. The first is that Artemisia remained in Ephesus to look after Xerxes’ heirs. This seems unlikely, as he would have had plenty of female attendants and servants to mind his children. The second, suggested by Photius around 1,300 years later, is that Artemisia fell in love with a man in Abydos who rejected her advances. In response, she blinded the man while he slept, then threw herself from a great height into the sea and drowned. This trope was common in ancient literature and may have inspired Photius to invent the story.

There is no hard evidence for what happened to Artemisia after she escorted Xerxes’ children to Ephesus. Her son, Pisindelis, succeeded her to the throne of Halicarnassus in 460 BCE, so we can assume she had passed away by then. As her date of birth is also unknown, we do not know how old she was at the end of her 20 years in power.

7. She Is a Popular Figure in Pop Culture

Artemisia I of Caria has been reimagined many times since her death, usually in connection with the story of the 300 Spartans at Thermopylae. Rudolph Mate’s 1962 blockbuster, The 300 Spartans, saw actress Anne Wakefield bring the character of Artemisia to the big screen. Wakefield’s portrayal showed Artemisia as a captivating woman who had enchanted Xerxes and seemingly had a hidden agenda.

Typical of cinema at the time, Artemisia was depicted as largely one-dimensional. The same cannot be said in the 2014 film 300: Rise of an Empire, where Artemisia, played by actress Eva Green, is shown as a fearsome warrior with a tragic backstory. In this adaptation, Artemisia convinces Xerxes to become a god-king and leads the onslaught against the Greeks at Artemisium. In the action sequences, Artemisia fights among men as she wields two swords, and dies in battle at the hands of Themistocles.

Artemisia has also appeared in multiple fictional written works, such as Roy Casagranda’s 2018 thriller about the Queen of Halicarnassus titled The Blood Throne of Caria, and Gore Vidal’s work called Creation, where she has a relationship with the general Mardonius. Moreover, multiple ships and naval vessels have been named Artemisia, particularly in the Middle East.