While the worship of personifications of abstract ideas seems to be one more concept that the Romans borrowed from the Greek world, these deities took on new importance among the Romans. For example, Victoria was much more important among the Romans than Nike was in Greek religion. These personifications, commonly called “Virtues” in the Roman context, became particularly important during the Imperial Period when the fortune of Rome centered on the person of the emperor.

On Divine Nature and Origins of the Virtues

We meet many personifications in Greek religion, with the Greek creation myths describing the first gods to emerge as entities such as Eros (love/desire) and Erebus (darkness). Later divine generations had children such as Nike (victory), Zelus (envy), Kratos (strength), and Bia (violent force). The Greeks managed to work these abstract personifications into the complex genealogy of their gods, but evidence of their worship in the Greek world is extremely rare. Instead, temples, festivals, and sacrifices were made to the Olympian gods, such as Zeus and Athena. So, while the Greeks understood these personifications to be divine, they were rarely worshiped.

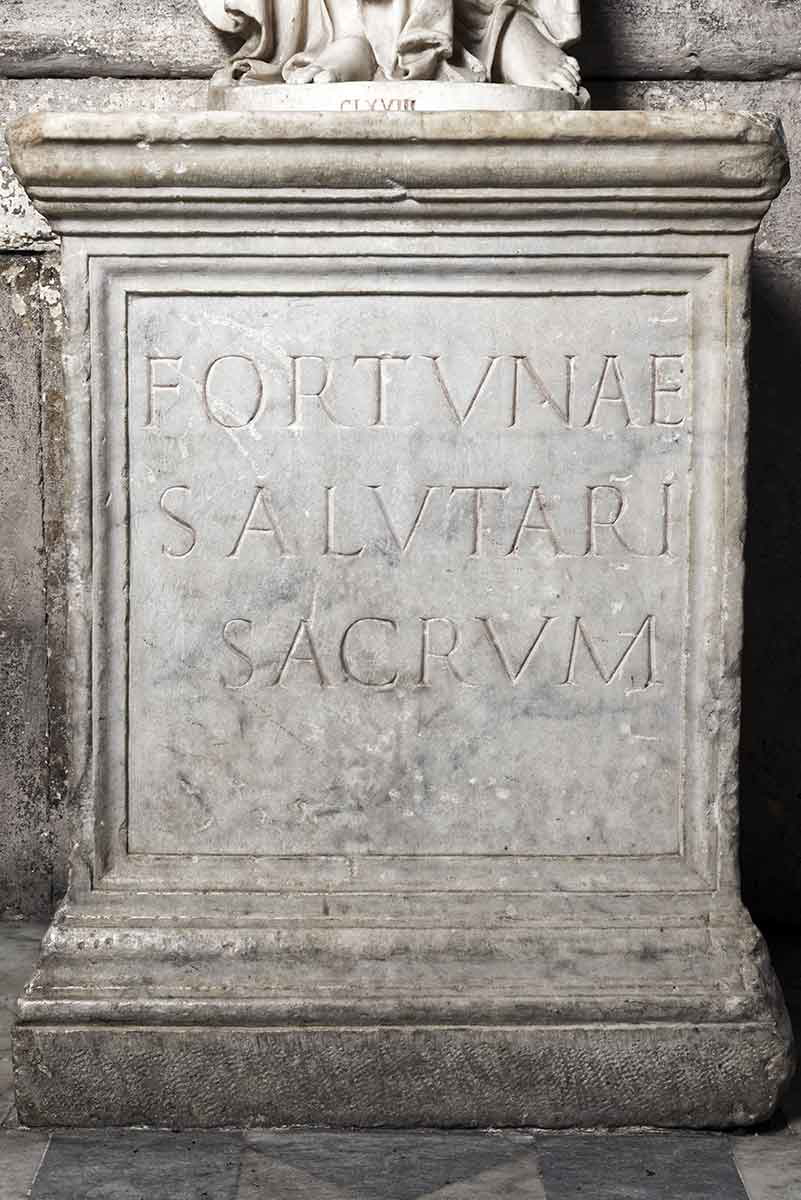

The Roman world was different. There are records of scores of temples dedicated to divine personifications, or Virtues, such as Victoria (victory), Concordia (concord), Fides (faith), and Mens (wisdom). This reflects the different attitudes of the Romans towards their gods. They believed that there were an infinite number of gods, but they focused their devotional energy on those who could have an impact on their lives. They established cults with these gods to open a dialogue with them, as they believed that winning the favor of the gods depended on proper ritual recognition. Therefore, a cult was a doorway through which negotiations could be made.

The late Republican senator and writer, Cicero, explains this ideology and how it resulted in the worship of the Virtues in his treatise On the Nature of the Gods:

“Thus far have I spoken concerning the universe, and also of the stars; from whence it is apparent that there is almost an infinite number of gods… there are many other natures which have with reason been deified by the wisest Grecians, and by our ancestors, in consideration of the benefits derived from them; for they were persuaded that whatever was of great utility to humankind must proceed from divine goodness, and the name of the deity was applied to that which the deity produced, as when we call corn Ceres, and wine Bacchus… And any quality, also, in which there was any singular virtue nominated a deity, such as Fides (faith) and Mens (wisdom) which are placed among the divinities in the Capitol…” (2.59-61)

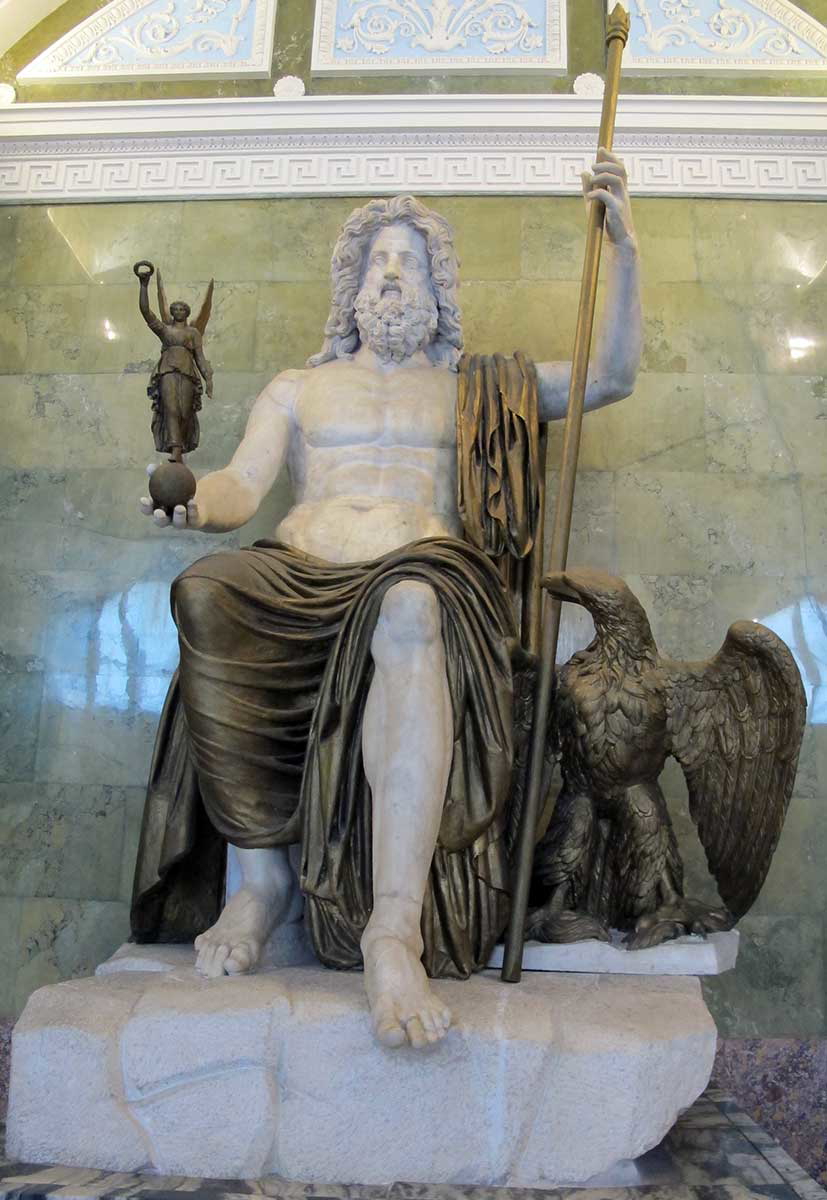

Even though these Virtues were considered deities, they could still be associated with other gods. For example, Jupiter, the principal god of the Roman state, was sometimes worshiped as Jupiter Liberator, even though Libertas was also a goddess. Venus, the Roman equivalent of Aphrodite, was sometimes worshiped as Venus Victrix, even though Victoria was also recognized as a goddess.

This duality does not seem to have posed a problem for the Romans, with Victoria considered a divine force, but victory could also be facilitated by gods such as Jupiter, Mars, and Venus. Nevertheless, there does seem to have been a hierarchy among the gods. Whenever the Arval Brethren—a popular priesthood among the Roman elite who have left extensive records—made a sacrifice to multiple deities, they always sacrificed first to the Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva, then to other Olympian deities, then to the Virtues, then to the Genius (guardian spirit) of the emperor, and finally to the Divi (deified emperors).

Virtues During the Roman Republic

The idea that Virtue deities were important to the health and success of the Roman state seems to have emerged early. The Temple of Concordia was reportedly vowed by Camillus in 367 BCE to thank the goddess for restoring peace and concord to Rome following the civil conflict caused by the Licinian-Sextian laws (Plutarch, Camillus 42). At least another two temples of Concordia were dedicated to Rome during the Republic, and from the late 2nd century BCE, one of them became a meeting house for the Roman Senate.

During the first years of the Hannibalic Wars in the 3rd century BCE, due to fear of the crisis and the immense number of ominous prodigies recorded, the Sibylline Books (a sacred collection of oracles) were consulted. They advised that a cult should be dedicated to Mens (knowledge). More than that, the ground for the temple site was to be consecrated via a live inhumation in the Forum Boarium of two Greeks and two Gauls (Livy, Roman History, 22-25).

Cicero’s treatise also confirms that many other temples and altars were dedicated throughout the Republic, as in his time he could also name dedications to Fides (faith), Ops (help), Salutis (safety), Libertas (liberty), and Victoria (victory).

In the very dying days of the Republic, we also hear of a temple being dedicated to Concordia Nova in 44 BCE with an annual festival in honor of the god. It was dedicated to the new peace brought to Rome by Julius Caesar’s victories, both foreign and civil (Cassius Dio, Roman History 44.4). But Caesar was assassinated within a few months of the new temple being vowed.

Victoria and Fortuna: From Republic to Principate

Following years of civil war, Octavian Caesar made himself the undisputed head of the Roman state. One way in which he celebrated this was by dedicating an altar to Victoria, the Ara Victoriae, in the Roman Senate house in 29 BCE to mark the defeat of Mark Antony and Cleopatra.

While there were many attempts to formalize Octavian’s position within the Republic, such as the special powers granted to the Second Triumvirate, the more-or-less final settlement came in 27 BCE, when the Octavian received the name Augustus.

This was an unprecedented title. While others had taken the name Pius (pious) and Felix (divinely lucky), there had never before been an Augustus. The word itself means “sacred” or “religious,” and it had previously been used in texts to describe things such as temples and cult statues. It didn’t really mean something that was divine, but rather something that was connected with the divine. This made sense within the Roman context. They believed that the prosperity of the Roman state depended on the favor of the divine. But Rome now also depended on Augustus, which suggested that he was godsent or a divine tool for delivering the prosperity of Rome.

Several dedications were made to Virtues during Augustus’s reign. Initially, they followed the Republican example. In addition to the altar of victory, an altar was dedicated to Fortuna Redux (fortune returned) in 19 BCE to celebrate Augustus’s return to Rome after a successful military campaign in the East. It was dedicated near the temple of Honor (honor) and Virtus (virtue) and it was ordered that the pontiffs and Vestal Virgins should perform sacrifices annually on the anniversary of his return. The sacrificial day was named “Augustalia” after the emperor (Augustus, Res Gestae 11).

The Cult of Augustan Virtues

Just a few years after the dedication to Fortuna Augusta, when Augustus returned from an expedition in Spain and Gaul in 13 BCE, the Senate voted him another altar. This time it was to be dedicated to Pax Augusta (Augustan peace), with magistrates, priests, and the Vestal Virgins making annual sacrifices. The altar was eventually dedicated on January 30, 9 BCE, the birthday of Augustus’s wife Livia, and the altar was decorated with a procession showing magistrates and priests, and also the members of Augustus’s family (Augustus, Res Gestae 12).

Applying the epithet Augusta to the name of the goddess Pax clearly changed the nature of this dedication, creating a new kind of Virtue. While Pax was still the goddess that embodied peace, her bounty was delivered through Augustus, much like the bounty of Libertas could be delivered through Jupiter Liberator. But the relationship was different. Jupiter, named first, commanded Libertas, while Libertas, named first, worked through Augustus.

Several other cults of Augustan virtues were established under Augustus. An altar was dedicated to Providentia Augusta (Augustan foresight), which was dedicated on June 26, the anniversary of Augustus’s adoption of Tiberius, which presumably means it was dedicated in 4 CE when he was adopted.

Another altar to Ops Augusta (Augustan help) was dedicated in 7 CE to commemorate Augustus’s role in alleviating famine in the city. The Temple of Concordia on the slopes of the Capitol was rededicated to Concordia Augusta in 10 CE. A statue of Justitia Augusta (Augustan justice) was dedicated in 13 CE, probably to celebrate Tiberius’s triumph that year.

These multiple dedications to Augustan virtues throughout the first emperor’s reign make it clear that there had been a shift in thinking. While the emperor himself was not divine and could not be worshiped as a god within the Roman state, the divine often worked through him for the benefit of the state. At the time, the Romans believed that this situation was best articulated by making dedications to personified Virtues connected to Augustus.

Continuing Imperial Virtues

The example of Augustus was followed by his successors, who also took the title Augustus to indicate their position within the state. It is unclear how many new cults dedicated to Augustan Virtues (also often called Imperial Virtues) were made over the following centuries. Only a few literary references and archaeological remains survive. The appearance of an Imperial Virtue on a coin may or may not have been indicative of a cult. It could just have been an image of propaganda.

Nevertheless, under the Julio-Claudians alone we know that there was a dedication to Libertas Augusta under Tiberius following the thwarting of his traitorous Praetorian Prefect Sejanus (Cassius Dio, 58.12.4). Evidence suggests that another dedication was made to Salus Augusta (Augustan health) during one of Livia’s illnesses to support her recovery. There seems to have been a dedication to Constantia Augusta (Augustan steadfastness) near the start of Claudius’s reign, probably signaling a return to prudence following the turbulence of Gaius Caligula’s reign. Under Nero, there seems to have been a dedication to Fecunditas Augusta (Augustan fertility) following the birth of Nero’s daughter (Tacitus, Annales 15.23).

Over 30 Imperial Virtues appear on imperial coinage between the reigns of Augustus and Commodus. In addition to those already mentioned we see, among others, Pietas (piety), Aeternitas (eternity), and Spes (hope). We also know that some of these virtues received sacrifices from records of sacrificial actions performed by priesthoods like the Arval Brethren.

The Arvals made sacrifices to the fertility deity Dea Dia, and also made imperial cult sacrifices for the emperor on occasions like the new year and imperial birthday, making sacrifices to the gods on behalf of the emperor for his health and prosperity. The vast majority of these imperial sacrifices were made to the Capitoline Triad and the Divi (defied previous emperors), but several Imperial Virtues also received sacrifices. Their surviving records for the Julio-Claudian and Flavian periods indicate sacrifices to Salus, Pax, Providentia, Concordia, Felicitas, Spes, Clementia, Victoria, Securitas, and Fortuna.

Interestingly, while sometimes the Virtues were referred to as Augustan, sometimes they had no qualifier, and other times they were referred to as Publica (public) or Populi Romani (of the Roman people). Despite the different nomenclature, the sacrifices were still made for the health and well-being of the emperor. While this adds confusion, it still shows that by this time, many Virtues had become intimately connected with the emperor.

Clementia Caesaris

The only cult of what could be called an Imperial Virtue that does not seem to align with the character of the other Augustan Virtues was dedicated by the Clementia Caesaris (clemency of Caesar) in the final days of the Republic.

Awarded in recognition of the clemency Caesar showed to those who opposed him, a temple was proposed but never built, in 44 BCE. The intention seems to have been that the temple would contain statues of equal size of Clementia and Caesar himself. According to Appian, the pair would be clasping hands (Civil Wars, 2.106.443). But Appian says that this was one of many temples decreed to Caesar as a god.

This would have represented a very different cult from that of the Augustan Virtues, as both the goddess Clementia and Caesar would receive sacrifices as divinities. But they were also clearly meant to be considered separate divinities, as indicated by the nature of the cult statues. In contrast, in the records of the Arval Brethren, we see the priests making sacrifices to Jupiter and Concordia Augusta for the health and prosperity of the emperor, with the emperor himself never receiving sacrifices.

But it was Caesar’s acceptance of these kinds of unprecedented honors that were in opposition to Roman sensibilities that contributed to the rejection of his rule by the Roman aristocracy and his assassination. Augustus learned from his example and made sure that he formulated his role within Roman religion in a different way.