Why was classical music significantly shaped by German philosophy? It would be reductive to suggest that Romantic philosophy, which flourished in German cities such as Jena, Heidelberg, and Berlin, was entirely a reaction against French and English Enlightenment philosophy, which had paid little attention to music. However, it is true that composers inside and outside the German states were emboldened by the new ideas about music proposed by Romantic philosophers. By the end of the 19th century, German philosophy and classical music were in constant mutual exchange.

What Did Early Romantic Philosophers Think of Music?

Before Romanticism, philosophers were not terribly interested in music. Enlightenment philosophy saw it as a system of sounds which might, formulaically, correspond to various emotions. Jean-Jacques Rousseau theorized about its origins in the pre-linguistic stage of human development, when rhythm and melody—rather than words—conveyed emotion and meaning. Nevertheless, Immanuel Kant rated music lower than other arts such as painting and literature, because it seems unable to represent objective reality.

Romantic and Idealist philosophers rethought this hierarchy, placing music above all other arts precisely because of this inscrutable relationship to the outer world and powerful connection to the inner world of the emotions.

G.W.F. Hegel, although he hesitated to claim music’s supremacy, nonetheless wrote that its power “consists in making resound, not the objective world itself, but, on the contrary, the manner in which the inmost self is moved to the depths of its own personality and conscious soul” (Hegel 2015, 891).

Romantic philosophy prized music because it obeys certain laws of mathematics and physics, and yet there are things about it and its effects that we simply cannot put our fingers on. Ludwig Tieck and W.H. Wackenroder, philosophers from the Jena circle of Romantic thought, wrote: “Without music the earth is like a desolate, as yet incomplete house that lacks its inhabitants. For this reason the earliest Greek and biblical history, indeed the history of every nation, begins with music” (Tieck and Wackenroder 1973, 102).

This sense of music’s fundamental position in human history and the human soul led Romantic philosophers to imagine their task in musical terms (however vague that might be in practice). The poet and philosopher Novalis wrote enthusiastically about “musical handling of the art of writing; one should write as the composer composes” (Schafer 1975, 9). Friedrich Schlegel, at the center of the Jena circle, went even further: “Every art has musical principles and when it is completed it becomes itself music. This is even true of philosophy and thus also, of course, of literature, perhaps also of life” (Schlegel 1957, 151).

For Idealist philosophers who questioned the existence of objective reality, music offered a compelling example of a phenomenon that, in its abstraction, seemed to transcend the measurable or observable world.

Moreover, music provided a good correlative for the aims of Idealist philosophy because forms such as the symphony represented the coexistence of unity and transcendence, or adherence to an intellectual system alongside striving for the unreachable. The symphony’s use of the entire orchestra, too, satisfied the democratic ideals of much Romantic philosophy.

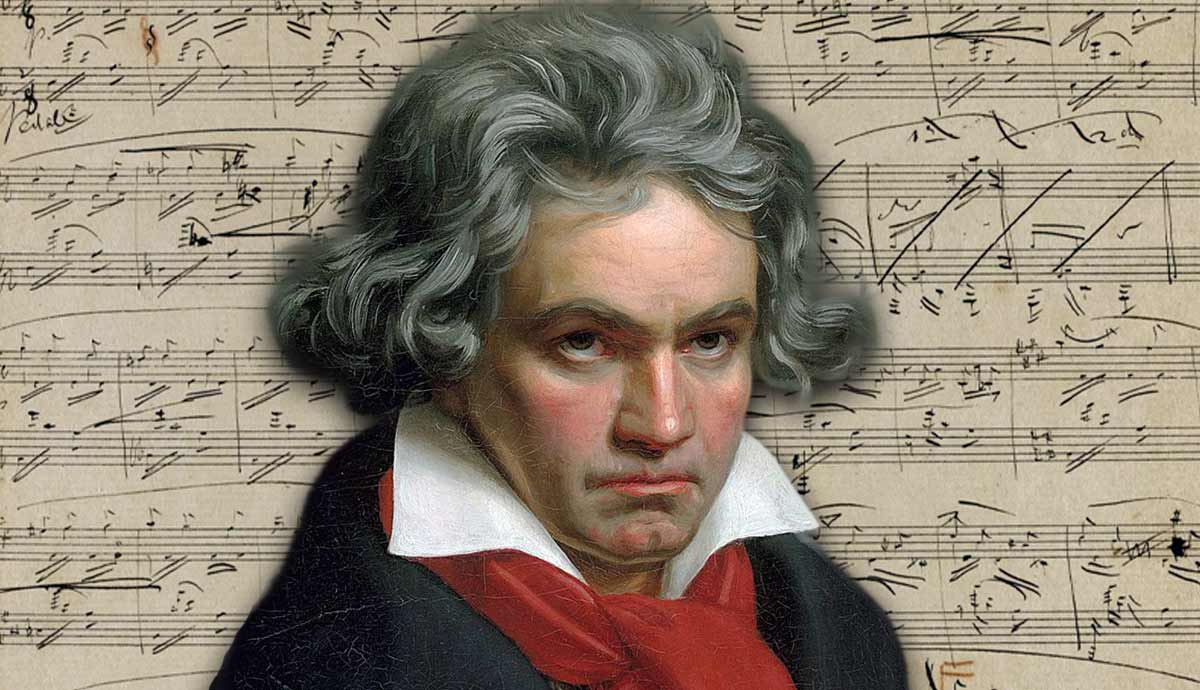

The symphonies of Ludwig van Beethoven, first appearing around the same time as much of this philosophical work, seemed to exemplify this balance, with their traditional four movements and, at the same time, a sense of something beyond. When Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony was first performed, author and music critic E.T.A. Hoffmann exalted it in a review as a gateway to (in ultra-Romantic terminology) “the infinite” and “inexpressible longing.”

Beethoven and Philosophy

Much Romantic philosophical exaltation of music seems to celebrate an abstract concept of music—perhaps music in its ideal form, music which had not yet been composed—rather than a specific piece or composer. Which came first: Romantic music, or the Romantic philosophy of music? Hoffmann’s review of Beethoven’s Fifth is a notable exception, where we can determine exactly which music inspired the philosophy.

In turn, philosophy shaped the legacy of Beethoven’s music. In 1807, around the time that Beethoven was composing his Fifth and Sixth Symphonies, Hegel published his first major work of philosophy, The Phenomenology of the Spirit. Theodor Adorno, writing much later, heard direct parallels: “Beethoven’s music is Hegel’s philosophy.”

Specifically, Adorno heard Hegel’s radical new placement of the spirit within the individual (as opposed to a divine outside force) in Beethoven’s innovations upon classical form. His symphonies broke with established rules, subsuming the audience’s consciousness of a four-movement structure in favor of an overwhelming sense of a unified journey towards something, like the inscrutable aims of Hegel’s philosophy, ultimately unattainable. This hardly mattered, though: in Romantic philosophy, the important thing was to strive towards it, and to achieve emancipation in the process.

We cannot be sure whether Beethoven read Hegel, but their common theme is emancipation. Hegel’s work brought about a new understanding of the subject, emancipated and self-governing. Beethoven’s music was heard as an emancipation from classical forms, at a time when composers themselves were also claiming emancipation from former obligations to work for patrons, either in royal courts or churches. With the emergence of a marketplace for music, they could consider themselves free to make the artistic decisions they wanted.

Composers shared in new ideas about the freedom of the individual, and especially about the importance of expressing interiority in artworks. Beethoven reportedly said, “I live only within my notes” (Salmen 1983, 268), encapsulating the new idea that pieces of music could reveal the souls of their creators.

Increasingly, following his death in 1827, Beethoven was celebrated as the archetypal Romantic artist, whose works charted a struggle for emancipation and transcendence. His final symphony, the Ninth, was the crowning glory of this struggle, its fourth movement culminating with an unprecedented move for a symphony: a triumphant combination of words and music, with a text based on Friedrich Schiller’s Ode to Joy.

Two Romantic Heroes: William Tell and Faust

Schiller, a playwright, historian, and philosopher, is responsible for bringing an important figure to the attention of Romantic composers in his 1804 play William Tell. Schiller was inspired by his friend Johann Wolfgang Goethe‘s travels to Switzerland, where he learned about the legendary huntsman who defies an oppressive regime in support of the peasantry. Tell is an ideal Romantic figure: revolutionary, individualist, committed to freedom above all.

The best-known adaptation of Schiller’s William Tell is the 1829 opera by Gioachino Rossini, with its famous overture. The character of William Tell also profoundly influenced Franz Liszt, who frequently performed his embellished piano transcription of the overture at concerts.

Liszt is generally associated with the strain of Romantic philosophy active in Paris during his years there in the 1830s. He read the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Auguste Comte. He also took a great interest in the radical Catholicism of Abbé Lamennais and the proto-socialism of Henri de Saint-Simon.

But William Tell, as represented by Schiller via Rossini, equally appealed to Liszt’s belief in a reorganization of society in favor of meritocracy. In Liszt’s view, composers, as artists who are granted superhuman abilities both to commune with God and to express the depths of the human condition, ought to be honored in society, not left to struggle in penury.

The second icon of Romantic philosophy for composers was Faust, popularized by Schiller’s friend Goethe in a play published in two parts in 1808 and 1832. Goethe took the medieval legend about the scholar’s pact with the Devil and made it into an archetypal Romantic tale, centered on a hero who makes his wager with Mephistopheles in the pursuit of not just knowledge, but transcendence.

Part One of the play was instantly popular in Germany and beyond, crystallizing notions of the conflicted Romantic hero. Composers in their droves wrote pieces inspired by Faust, its characters, and narrative: Charles Gounod (Faust, opera, 1859), Hector Berlioz (The Damnation of Faust, opera, 1846), Franz Liszt (the Faust Symphony, 1857, and four ‘Mephisto’ Waltzes, 1859-85), Richard Wagner (a Faust Overture from an abandoned Faust Symphony, 1839-40), Robert Schumann (Scenes from Goethe’s Faust, an operatic work, 1844-53), and Franz Schubert (‘Gretchen am Spinnrade’, a Lied or song taking its text from Part One of the play, 1814). Later in the Romantic period, Modest Mussorgsky (‘Song of the Flea’, 1879) and Gustav Mahler (Part Two of the Eighth Symphony, 1910) set words from Goethe’s Faust to music.

The Romantic Fragment

In a famous statement, Friedrich Schlegel declared: “A fragment, like a miniature work of art, has to be entirely isolated from the surrounding world and be complete in itself like a porcupine” (Schlegel 1991, 45). The statement itself appears in a work of fragmentary philosophical propositions, which Schlegel likened to the autonomous perfection of a single porcupine spine.

Many Romantic works, across various arts, were more or less intentionally fragmentary. Samuel Taylor Coleridge provided an infamous anecdote about being interrupted by a visitor from the nearby town of Porlock during the composition of his poem Kubla Khan (1797). Other works were left unfinished at their creator’s death: Lord Byron‘s Don Juan (1819-24), or Felix Mendelssohn’s oratorio Christus (1847).

Some composers, though, set out to write works which fulfilled Schlegel’s idea of the “miniature work of art,” not considered in relation to a wider whole but recognized as complete in themselves. Frédéric Chopin‘s 24 preludes for solo piano (1839) are a case in point. The word ‘prelude’ refers to a piece of music which traditionally introduces a longer work, and J.S. Bach (Chopin’s precedent for the collection) had written preludes as exercises for the pianist to improve their skills in every key. Chopin, however, approached the form as a genre in itself, conferring on each of his preludes a distinctive character, allowing them to stand alone and reconceptualizing the worth of miniature pieces.

Another composer who approached traditionally smaller and dependent musical forms as complete and independent was Robert Schumann. Many of his works, especially for solo piano, are collections of miniatures, sometimes fragmentary in nature: Carnaval (1834-35), Fantasiestücke (1837, inspired by a collection of writings by E.T.A. Hoffmann, one of Schumann’s favorite authors), and Dichterliebe (1840, a song cycle with lyrics by the Romantic poet Heinrich Heine).

Schumann composed several songs conforming to the Romantic trope of Wanderlieder (literally, songs of wandering), which is linked to the notion of fragmentation. If many Romantic works are necessarily unfinished because they strive to represent something ineffable and uncapturable, so is the attempt to know one’s own soul a necessarily unfinished journey.

A voracious reader of Romantic literature and philosophy, Schumann took seriously art’s role in guiding individuals on this journey, futile as it must ultimately be. Echoing Hegel’s sense of the deep-rooted significance of music, he wrote: “[m]usic speaks the most universal of languages, that through which the soul finds itself inspired in a free, indefinite manner, and yet feels itself at home” (Schumann 1984, 360).

Schumann subscribed wholeheartedly to the new understanding of music as vitally important and the composer as a quasi-divine figure: “[l]ike a Greek god, the artist must associate in a friendly fashion with mankind and with life; but when life dares touch him, let him also disappear and leave nothing behind him save clouds” (Schumann 1983, 40).

He was not the only person in this period who would look to Ancient Greece to exalt the role of the artist in creating paradoxically fragmentary and complete works in the quest for knowledge and transcendence.

Wagner and Philosophy

Friedrich Nietzsche is known for fragmentary philosophical statements, otherwise called aphorisms. He was probably the most important philosopher in Richard Wagner’s life, but he was not the first philosopher whom the composer encountered.

Wagner enrolled at the University of Leipzig, Goethe’s alma mater, in 1831, the year Hegel died. The student entered an intellectual atmosphere dominated by the idealism of Hegel, Johann Gottlieb Fichte, and Johann Gottfried Herder. Herder’s conception of the true German spirit as manifest in das Volk, or ordinary people and folk traditions, would be hugely important to Wagner’s art. Indeed, Wagner would attempt to synthesize these ideas about individual freedom and the collective spirit of the nation in his operatic works.

The next seismic philosophical discovery for Wagner came in 1854, when he read Arthur Schopenhauer‘s The World as Will and Representation, first published in 1818 but languishing in near-obscurity until the second edition in 1844. Schopenhauer‘s work had an instant impact on the music drama Wagner was devising at the time, Tristan und Isolde (premiered in 1865). The lovers, drawn from Arthurian legend, seek in each other release from what Schopenhauer calls the Will: a compulsive, unconscious drive undergirding our lives.

Perhaps unsurprisingly given that Schopenhauer‘s is a pessimist philosophy, Tristan and Isolde are doomed in their endeavor, their Will manifesting as a powerful sexual desire which can only lead to destruction.

Wagner’s music itself was also influenced by Schopenhauer, embodying his claim that, out of all the arts, music was the most direct manifestation of the Will. Tristan und Isolde is celebrated for its intense cycles of unresolved harmony, building to a climax that seems like it will never come.

In paying meticulous attention to every artistic aspect of his work—not only the music, but the words, the staging, sets, costumes, and theater design—Wagner was influenced by Ancient Greek philosophy, filtered through early-nineteenth-century Romanticism. August Wilhelm Schlegel, brother of Friedrich, had written: “We should strive to bring the arts closer together and search for bridges from one to the other” (Schafer 1975, 9). Wagner revived this goal in his concept of the Gesamtkunstwerk, or total work of art.

Wagner first proposed the Gesamtkunstwerk in 1849, so he was steeped in ancient Greek ideas about the roles and relationships of the arts long before he encountered the philosopher whose own interest in Ancient Greece would become intertwined with his own for posterity.

In fact, Nietzsche had Wagner in mind when he wrote, in 1872’s The Birth of Tragedy, that it would be possible to recapture the ideal synthesis of Apollonian order and Dionysian disorder in modern art.

Nietzsche was close with Wagner and his wife Cosima, both of whom had personally encouraged the philosopher to write The Birth of Tragedy, a work influenced by Schopenhauer’s dichotomy of representation and Will, and by earlier Romantic philosophy.

The work Wagner subsequently produced—the Ring tetralogy—had been in development for several years already, so cannot be seen as directly influenced by Nietzsche. Still, it was a continued attempt to recapture the ancient Greek total works of art, which Nietzsche had celebrated.

Despite this, Nietzsche infamously broke with Wagner following the first Bayreuth Festival in 1876, writing about the spectacle of experiencing the Ring at the custom-built theater as dangerous, hypnotic, and even liable to cause madness. The Case of Wagner (1888) and Nietzsche contra Wagner (1889) were published after the composer’s death, but describe the philosopher’s disillusionment with Wagner’s German nationalism, which came with a great deal of anti-Semitism.

Many statements in these texts are aphoristic, in keeping with the earlier Romantic celebration of fragmentation. Sadly, given what Nietzsche warns about Wagner as a “disease” who has “made music sick” (Nietzsche 1911, 11), these two anti-Wagner tracts were the last texts Nietzsche published before succumbing to mental illness.

This has left the debate open as to whether his attacks on Wagner were personally motivated, or a result of his encroaching illness, or a carefully considered final word on the long and complex relationship between German philosophy and classical music in the 19th century.

Bibliography

Hegel, G.W.F. (2015). Hegel’s Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, volume 2, ed. and trans. T.M. Knox. Oxford University Press.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Case of Wagner, Nietzsche Contra Wagner, and Selected Aphorisms, trans. Anthony M. Ludovici. T.N. Foulis.

Salmen, Walter (1983). The Social Status of the Professional Musician from the Middle Ages to the Nineteenth Century. Pendragon Press.

Schafer, R. Murray (1975). E.T.A Hoffmann and Music. University of Toronto Press.

Schlegel, Friedrich (1957). Literary Notebooks 1797–1807, ed. Hans Eichner. University of London Press.

Schlegel, Friedrich (1991). Philosophical Fragments. University of Minnesota Press.

Schumann, Robert (1983). On Music and Musicians, trans. Paul Rosenfeld. University of California Press.

Schumann, Robert (1984). ‘From the Writings of Schumann,’ in Music in the Western World: A History in Documents, ed. Piero Weiss & Richard Taruskin. Schirmer Books.

Tieck, Ludwig and W.H. Wackenroder (1973). Phantasien über die Kunst, trans. Andrew Bowie in ‘Music and the rise of aesthetics’, in The Cambridge History of Nineteenth-Century Music, ed. Jim Sanson, 2001, 29-54.