During the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550-1200 BCE), an Indo-European people known as the Hittites expanded beyond their borders in central Anatolia to create an empire. The Hittites conquered most of Anatolia, the northern Levant, and destroyed the Mitanni Kingdom, which they accomplished through their martial culture. The Hittite culture was in many ways built for war. The Hittite religion encouraged warfare, primarily through their fiery storm god. The Hittites were also quite industrious and innovative, devising special chariots that met their needs along with effective weapons and armor. Evidence from Egypt suggests that the Hittites fielded a large and professional standing army that was organized into divisions. All of these factors combined to deliver success to the Hittite kings throughout the ancient Near East.

Hittite Religion and Warfare

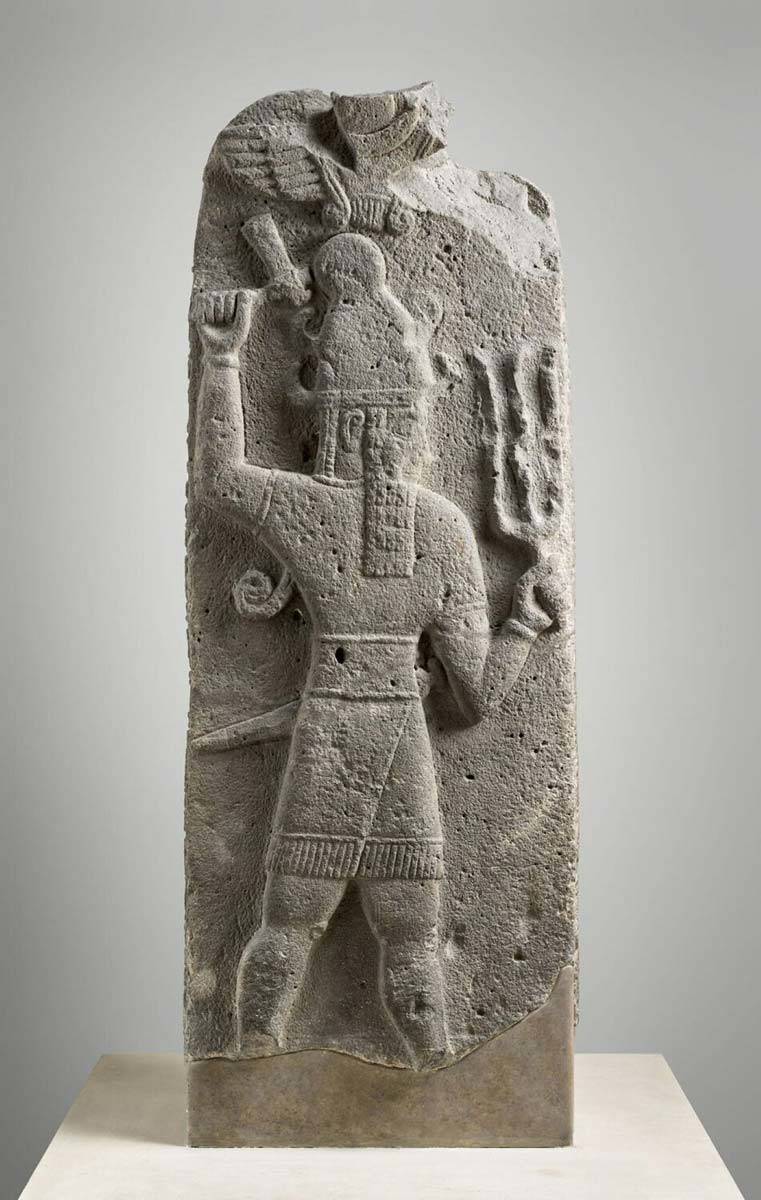

The Hittites followed a polytheistic religion, which was similar to other peoples of the Bronze Age Near East. Some elements of the Hittite religion were fairly eclectic. Deities and myths were drawn from Mesopotamia and the neighboring Hurrian people, but many parts were uniquely Hittite. The primary god of the Hittite pantheon was usually referred to simply as the “Storm-God” in texts, although he was occasionally named Tarhuna. The Storm-God was a god of the weather, fertility, and war, much like other Indo-European gods. The Aryan Indra, the Greek Zeus, and the Norse Thor all shared similar attributes with the Storm-God. And it is no coincidence that those were also martial societies.

The Hittites went to war for most of the same reasons people still do: resources, border expansion, and prestige. Cuneiform texts in the Hittite language indicate that war was also done partially to propitiate the Storm-God. The Hittite King Suppiluliuma I (ruled c. 1344-1322 BCE) attacked his major rival, Mitanni. The first attack was unsuccessful, so the Hittite king did a flanking maneuver on Mittani that had better results. Suppiluliuma sacked the Mitanni capital of Washshukanni and created a political vacuum that led to the Mitanni people killing their king, Tushratta. Suppiluliuma then installed the son of Tushratta, Kurtiwaza, as king and had him declare his fealty before the Storm God.

“I, the Sun Suppiluliuma, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant, the favorite of the Storm-god, went to war. Because of king Tusratta’s presumptuousness I crossed the Euphrates and invaded the country of Isuwa. . . I, the Sun Suppiluliuma, the great king, the king of the Hatti land, the valiant, the favorite of the Storm-god, reached the country of Alse and captured the provincial center Kutmar. To Antar-atal of the country of Alse I presented it as a gift. I proceeded to the provincial center Suta and ransacked it. I reached Wassukanni. The inhabitants of the provincial center Suta together with their cattle, sheep (and) horses, together with their possessions and together with their deportees I brought to the Hatti land, Tusratta, the king, had departed, he did not come to meet me in battle.”

Hittite Warfare Technology

The chariot was the preeminent vehicle of war during the Late Bronze Age. The Egyptians are perhaps best known for their use of chariots, but the Hittites developed their own style of chariots that were equally effective. Hittite chariots, like most chariots of the era, consisted of a wooden frame covered with leather. As with their Egyptian counterparts, chariot warfare was the core of Hittite military tactics, but Hittite chariots had a couple of notable differences.

The axle of Hittite chariots was attached to the middle of the vehicle rather than the rear, as they were with Egyptian chariots. The design meant that Hittite chariots were bigger and heavier, which had both advantages and disadvantages. The primary advantage was that a Hittite chariot crew could carry three men: a driver, a shield bearer, and a spear thrower. Egyptian chariot crews consisted of only two men: the driver who doubled as an archer and the shield bearer. The larger size of Hittite chariots made them less maneuverable, but it should be noted that Egyptian chariot drivers had to do two tasks, which were likely difficult to do simultaneously.

The Hittite infantry was similar to other infantry forces of the era, although they may have had the luxury of some better weapons. Hittite armor usually consisted of a leather sleeveless jacket that was worn over a corselet that was probably bronze. Most of the weapons used by the Hittites were also bronze, yet they may have utilized iron at times. It is known that the Hittites developed an iron industry toward the end of the Bronze Age. With that said, there is little evidence that the Hittites used iron weapons extensively, although they could have been utilized locally to their advantage.

The Hittites appear to have developed successful tactics that may have influenced later peoples. The infantry would fight in a phalanx formation with long spears and then switch to daggers if the phalanx was broken. The Hittite military also differed from their Egyptian counterparts with the use of the bow. Whereas Egyptian chariots used compound bows extensively, it appears the infantry were the only Hittite soldiers to use the bow, and they were not compound bows.

Battlefield Strategies

The vast majority of the Hittite primary source evidence indicates little about Hittite battlefield tactics. Archaeological evidence has revealed what type of weapons they used and texts, such as the Suppiluliuma document cited earlier, only relate the results of military campaigns. The Egyptians, however, documented one particular battle with the Hittites that helps to illuminate some of the battlefield tactics the latter used.

The Battle of Kadesh was fought between the Egyptians and the Hittites near the Levantine city of Kadesh in about the year 1274 BCE. The battle was fought for control over the Levant, which was contested by the two great Late Bronze Age Near Eastern powers. The factors that led to it, as well as the results, are less important here than the tactics the Hittites used. It can be presumed that many of the same tactics the Hittites used at Kadesh they also used in ancient Anatolia and the Near East.

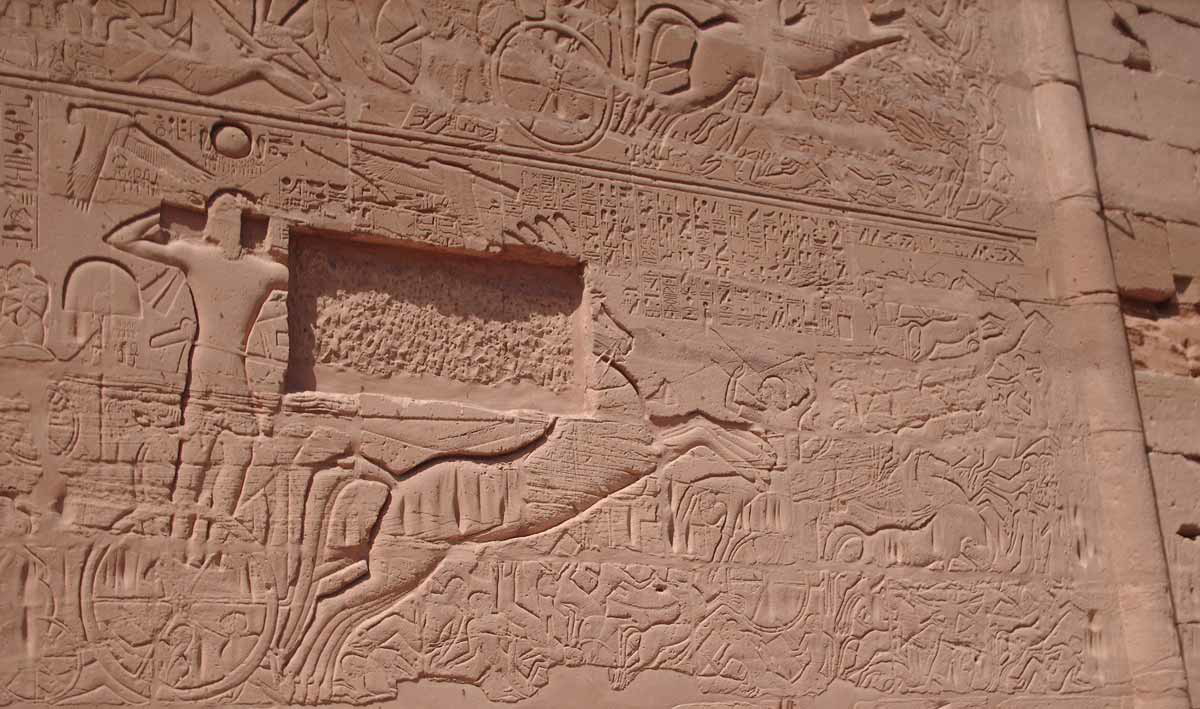

The Battle of Kadesh is the best documented ancient battle prior to the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. The battle was so important that the Egyptians recorded it in six hieroglyphic versions that were inscribed on numerous temples. It was also recounted in a cuneiform letter from Ramesses II (ruled c. 1279-1213 BCE) of Egypt to Hattusili II (reigned c. 1267-1237 BCE) of Hatti. Although the texts and the accompanying pictorial reliefs focus on the Egyptian army, the Hittites are mentioned and depicted enough for one to create an image of their tactics.

The Order of the Hittite Army

The Egyptian texts do not give any precise numbers of either side. Modern scholars, though, have made estimates based on the casualty counts and the formation of the Egyptian army. The Egyptian army was divided into four primary divisions that were named after the most important New Kingdom gods: Amun, Ra, Ptah, and Seth. The Egyptians were also augmented by a local auxiliary force known as the Na‘arn. Late 19th and early 20th century American Egyptologist James Henry Breasted believed that each army fielded about 20,000 men. Spalinger has more recently argued that the size of an Egyptian division was approximately 5,000 men, with the total coming to about 30,000 to 40,000 men when local and auxiliary forces are considered. He argued that the Hittite army had a numerical advantage of 5,000 to 10,000 men.

Breasted argued that the Hittite army was primarily Canaanite allies/vassals, as indicated by the Egyptian inscriptions. Part of the text read:

“Look the vile Chief of Hatti has come together with the many countries who are with him, whom he has brought with him as allies, the land of Dardany, the land of Nahrin, that of Keshkesh, those of Masa, those of Pidasa, the land of Ugarit, that of Irun, the land of Inesa, Mushanet, Kadesh, Khaleb, and the entire land of Kedy.”

The Hittites’ use of so many non-Hittite forces is not extraordinary. It is difficult to determine if the majority of the Hittite forces were non-Hittite and it should be remembered that the Egyptians also used the non-Egyptian Na‘arn and Sherden. The Sherden, who served as Ramesses’ personal bodyguards, were possibly from the western Mediterranean. In later decades the Sherden joined with the Sea Peoples in their attempted invasions of Egypt. So, it may be that the Hittites were more reliant upon foreign forces in their army, which could be positive or negative, depending upon the situation. It may also be that the Egyptians stressed the non-Hittite complexion of the Hittite army for propaganda purposes.

The pictorial reliefs show that both armies had elite bodyguards who protected the kings leading the forces into the battle. Ramesses II was protected by a force known as the Sherden or Shardana, while King Muwatalli II (ruled c. 1295-1275) entered the fray with his bodyguards. The Hittite royal bodyguards were known as the Teher warriors, although, unfortunately, little more is known about them.

The battle began with Muwatalli leading an attack of up to 2,500 chariots on the Egyptians. The number is taken from Egyptian texts, so Spalinger and other scholars are skeptical, yet the number should be considered in the wider context. Because chariots formed the backbone of both armies, it is not difficult to believe that the Hittites would have attacked with 2,500 chariots. With three-man crews, the total number would have been 7,500, or less than half of the total number of the Hittite army Breasted gave and around 15-20 percent of the total army per Spalinger’s numbers.

The Battle of Kadesh was a tactical victory for the Egyptians, as they won the day. But the Hittites won a strategic victory because the Egyptians were not able to hold the territory. The battle proved to be the apex of Hittite military power, as the Egyptians and Hittites later signed a permanent military treaty. The Hittite Empire then collapsed in the midst of the Sea Peoples invasion of c. 1200 BCE. The Hittites left behind an impressive military legacy that was driven by several factors. The Hittite religion gave the army the will to fight while their military technologies and strategies made them successful on the battlefield.