summary

- Invading Barbarians: The Lombards, a Germanic tribe, migrated into northern Italy in 568 CE as a horde of warriors accompanied by their extended households.

- Tribe to Monarchy: They were a tribal society that was unified under King Alboin to advance into Italy and make their capital at Pavia, but their duchies remained largely independent.

- Cultural Shifts: They mixed their Germanic traditions and religions with Italian customs, for example, introducing a written law code, and converted to Christianity.

- Fall of the Lombards: Lombard ambitions to expand south prompted the Pope to invite the Frankish king Charlemagne to successfully conquer the Lombards in 774 CE.

As the Roman Empire was collapsing in the West, the power vacuum drew countless tribes into the fractured landscape of Italy. Among them were the Lombards, also known as Langobards, a Germanic tribe whose name derives from their long beards. Often overshadowed by the more famous Visigoths or Franks, the Langobards established a kingdom in Italy that would last for over two centuries, outliving many of their barbarian peers. Arriving in 568 CE under their ambitious king Alboin, the Langobards swept through a weakened peninsula still recovering from war and plague. But they were more than mere conquerors. Over time, these so-called “barbarians” embraced Latin culture, adopted Roman law, and evolved from tribal warbands into sophisticated rulers.

Who Were the Lombards?

The roots of the Langobards reach deep into the shadows of pre-Roman Europe. According to their own origin legend, recorded in the Origo Gentis Langobardorum in the 7th century, the Langobards came from an island called Scadanan, most commonly identified with Scandinavia, from where they gradually migrated southward over a long period of time.

By the first century CE, Roman historians such as Tacitus were already familiar with the Langobards’ fierce independence and warlike nature. At that time, they inhabited regions around the lower Elbe River, in what is now northern Germany. The Langobards were not yet a unified kingdom but rather a loose confederation of warrior clans who shared a common language, religion, and customs. Like many Germanic tribes, they worshiped a pantheon of gods similar to those found in Norse mythology and practiced tribal law based on customary traditions.

By the 5th century CE, the Langobards had migrated further south into Pannonia (in present-day western Hungary and eastern Austria), where they interacted with the crumbling Roman world and neighboring tribes such as the Heruli, Gepids, and Ostrogoths. In Pannonia, they began adopting more centralized political structures under charismatic leaders, or duces, eventually unifying under a monarchy. Among the most prominent was King Alboin, who led the Langobards into Italy and forever changed their history.

How the Lombards Took Over Italy

The Lombard conquest of Italy in 568 was not a sudden act of aggression, but the culmination of decades of migration, alliance-building, and strategic opportunism. By the mid-sixth century, Lombard warriors had already established themselves as a powerful force in Pannonia. They had even fought both against and alongside the Byzantines in their wars against the Ostrogoths. At the same time, the Western Roman Empire was falling deeper into disarray, a situation that the Lombard king Alboin skillfully exploited.

In 568, Alboin led a coalition of Lombards, Saxons, Gepids, Bulgars, and other tribes across the Julian Alps into Italy. This was not a full-scale military invasion, but rather a massive migratory wave led by warrior-aristocrats, followed by their families and dependents. The strategy proved successful, as the exhausted Byzantine Empire could offer little support to the western part of the former empire.

The Lombards quickly captured cities across northern Italy, including Milan and Verona. After a three-year siege, they also took Pavia, which became their capital. Alboin then declared himself rex Langobardorum, King of the Lombards. But Alboin’s reign in Italy was short-lived, as he was assassinated that same year. This may have been at the instigation of his wife, Rosamund, a Gepid princess whose father Alboin had killed and whose skull he had turned into a drinking cup. His death sparked political instability, but the Lombards continued their expansion.

The Lombard Duchies and Political Fragmentation

After the assassination of King Alboin, the Lombard kingdom found itself in a major crisis. Without a centralized authority, the Lombards entered a period of political fragmentation that would characterize much of their rule in Italy. This period is commonly known as the Rule of the Dukes (Interregnum Ducorum).

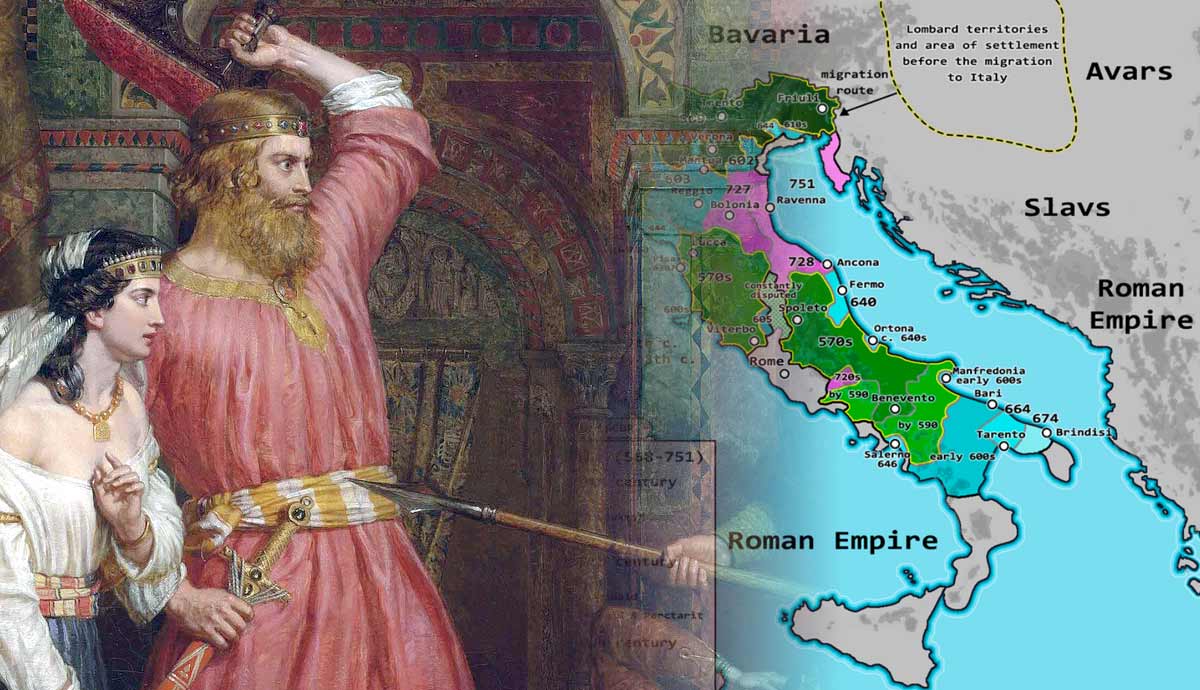

King Alboin had no direct heir. Instead, 30 military commanders known as dukes took control of various cities and territories. Each of them ruled independently over their own duchy with the support of local armies and elites. Loyalty often shifted depending on regional interests. During this time, we can no longer speak of a large, unified Lombard kingdom. Some of the most significant duchies included the Duchy of Spoleto in central Italy, ruled by Faroald I; the Duchy of Benevento in the south, ruled by Zotto; and the duchies of Friuli, Trento, Brescia, and Bergamo in the north.

This fragmented system had both advantages and disadvantages. Dukes ruled according to local customs and could respond more swiftly to threats, but cooperation between duchies was often hindered by rivalries among military leaders. This made the Lombards vulnerable to external threats. It wasn’t until 584, in response to frequent Frankish incursions, that the dukes were forced to restore the monarchy. Authari, the son of a former king Cleph, was elected as king. With this decision, the Lombard kingdom once again came under centralized rule. Nevertheless, it now functioned more as a loose federation of duchies rather than a unified state.

Life Among the Lombards: Customs, Religion & Culture

Early Lombard society was tribal and patriarchal. At the head of the tribe stood the king, followed by powerful dukes, nobles, and a class of free men called the arimanni, who formed the backbone of the formidable Lombard army. Below them were freedmen, slaves, and servile laborers tied to the land. Lombard clans were tightly knit, and blood feuds and honor-based retaliation were common forms of justice before codified law began to take shape. Wealth was measured in land, livestock, and warrior prestige.

Until their arrival in Italy, the Lombards followed laws based on tradition, until King Rothari issued the first written Lombard legal code known as the Edictum Rothari in 643 CE. It combined Germanic principles like wergild (compensation payments for injury or death) with the Roman legal structure. The early Lombards practiced a polytheistic paganism similar to Norse and other Germanic religions. Their deities included Odan (analogous to the Norse Odin) and Frea (like the Norse Freyja). However, as they moved southward, they gradually adopted Christian beliefs and customs, eventually converting to Arian Christianity. From the time of Queen Theodelinda, toward the end of the 6th century CE, the majority of Lombards transitioned to Catholicism.

They spoke a type of Germanic language that is now extinct and left behind very few written records. On the other hand, the Lombards left a rich archaeological legacy: their graves were filled with weapons, jewelry, and personal belongings. Their settlements followed Roman patterns and Romanesque architecture, and one of their most famous surviving monuments is the Tempietto Longobardo church in Cividale del Friuli.

End of the Lombards: Charlemagne & the Fall of the Kingdom

The Franks, under the leadership of Charlemagne, had strong imperial ambitions that would reshape the medieval West. For the Langobards, this marked the end of two centuries of rule in Italy. In the decades leading up to the collapse of the Lombard kingdom, tensions between the Lombards and the Papacy had been steadily rising. The main cause was the ambition of Lombard kings, especially King Desiderius, to expand further into central Italy, which the popes feared would threaten their autonomy.

Pope Hadrian I sought help from Charlemagne, son of Pepin the Short and the newly crowned king of the Franks. Charlemagne had both personal and political reasons to intervene. He had been briefly married to Desiderius’s daughter, a marriage and alliance that left a bitter aftertaste. He also viewed Lombard expansion as a significant political threat. In 773, after receiving an official request for help from the Pope, he led a Frankish army across the Alps.

By the spring of the following year, Pavia, the main Lombard stronghold, had fallen. Desiderius was exiled to a monastery, most likely at Corbie in northern France. Charlemagne entered Pavia in triumph and declared himself rex Langobardorum, King of the Lombards. This was the first time in Western Europe that a non-Italian ruler had taken the crown of a barbarian kingdom without completely destroying it.

Although the Lombard kingdom was extinguished by Charlemagne’s conquest, its cultural and social influence did not disappear overnight. The duchies of Spoleto and Benevento continued to exist into the 10th century, preserving the Lombard language and customs. Nevertheless, in most of Lombardy, the arrival of the Franks brought profound administrative, social, and political changes.