Among the more mundane yet important advances people in the ancient world made was the construction of roads. Roads allowed people to move troops, conduct long-distance trade, and exchange ideas. Many of the early roads were simply well-trodden paths that became important conduits, while others were highly engineered expressways that were a testament to ancient construction techniques. The following article surveys the development of some of the most important roads in the ancient world, from ancient Egypt to the Roman Empire and the Silk Road that connected the Far East.

Egyptian Roads: The Ways of Horus

Ancient Egypt may seem like a strange place to begin a survey of ancient road building. After all, Egypt was a riverine civilization, with most of the population living and working within walking distance of the banks of the Nile River. Because of this, most long-distance travel in ancient Egypt was done by boat. With that said, there were roads located on Egypt’s periphery that were documented as far back as the Old Kingdom.

One of the best documented Old Kingdom roads is referenced in the autobiography of Harkhuf, the governor of Egypt under King Pepi II of Egypt (ruled c. 2278-2184 BCE). The text mentions how Harkhuf led an expedition into an interior African land known as Yam, partially along a path called the “Yebu Road.”

“His majesty sent me a second time alone. I went up the Yebu road and came down via Meher, Terers, and Irtjetji (which are in) Irtjet in the space of eight months.”

Despite this connection, the Egyptians continued to rely on river and sea ships for contact with the outside world until the New Kingdom.

Egypt entered the New Kingdom in about 1550 BCE and immediately became an imperial power. After expelling the Hyksos from the Delta, the Egyptians pushed further north into the Levant, establishing hegemony over the southern part of the region (Shaw, 2004). The situation meant that the Egyptians had to be ready to put down potential Canaanite rebellions in the Levant and possible Hittite encroachment.

Egypt’s imperial status also put it on par with the other great kingdoms of the Late Bronze Age Near East, including Babylon, Hatti, Mitanni, and Alashiya (Van de Mieroop, 2024). Although these great powers were, at times, adversarial, they were more often engaged in peaceful trade and diplomacy with each other. Therefore, land routes were needed to move troops, merchants, and diplomats. The Egyptians primarily traveled along the coastline with their adaptable ships, but a system of roads was needed to connect the Delta to the Levant. The Egyptians solved this problem by developing a road system known as the Waut Horu, or “Ways of Horus” (Gardiner, 1920).

The Ways of Horus was primarily one road that went from the fortress of Sile near the Pelusiac branch of the Nile River to Gaza. The route followed near the Mediterranean coastline for almost 100 miles before terminating in the southern Levant (Redford, 1993). By Egypt’s 19th dynasty, at least a dozen way stations were located along the route, in addition to numerous garrisons.

Neo-Assyrian Roads: Near Eastern Connections

The Assyrians were among the most powerful Near Eastern peoples in the Late Bronze Age and early Iron Age, becoming prominent through efficient and brutal warfare. The era that modern scholars have termed the “Neo-Assyrian Empire” (934-610 BCE) was the apex of Assyrian power in the region. Ambitious and capable Assyrian kings, such as Ashurnasirpal II, Esarhaddon, and Ashurbanipal, created the largest empire in the Near East at that time. The empire covered more land and had more people than any other previous empire, so reliable and efficient transportation networks were needed (Haywood, 2005).

Most major Assyrian cities were located along the Tigris River, so boats could connect troops, diplomats, and merchants with central Mesopotamia and the Persian Gulf. Although river and sea travel was efficient, the Assyrian Empire stretched north into Anatolia and west into the Levant, and even briefly into Egypt. A network of roads was developed to connect the Assyrian heartland with the Levant and Anatolia.

As with their Egyptian predecessors, the Assyrian roads probably started as little more than commonly used paths. Later, the Assyrian authorities put more effort into developing the system. General maintenance was probably the responsibility of provincial governors. The larger routes probably had way stations where those who were authorized could rest and exchange their tired mules for a fresh team. The facilities could only be used by those who had a royal document of authorization (Haywood, 2005).

Achaemenid Persian Empire: The Royal Road

It is likely the Assyrian roads outlived their empire. After the Assyrian Empire collapsed in the late 7th century BCE, the Achaemenid Persians filled the void by creating an even greater empire in the 6th century BCE. Stretching from Bactria (modern-day Afghanistan) to Egypt, the Achaemenid Empire needed a state-of-the-art road system to keep it connected. Although there were many different roads, the Royal Road went from Sardis to Susa. The capital cities of Pasargadae, Persepolis, Susa, Babylon, and Ecbatana were connected on a highway network that was roughly a quadrilateral. The 5th-century Greek historian Herodotus gave a detailed description of the Royal Road in his Histories.

“At intervals all along the road are recognized stations, with excellent inns, and the road itself is safe to travel by, as it never leaves inhabited country. In Lydia and Phrygia, over a distance of 94 ½ parasangs – about 330 miles – there are 20 stations. . . Thus the total number of stations, or posthouses, on the road from Sardis to Susa is 111.”

It is believed that between the two foremost Achaemenid cities of Persepolis and Susa, there were 20 fully-equipped stations. As with the earlier Assyrian roads, access was controlled, and travelers on the Persian roads were required to have permits. In addition to the primary Royal Road that connected Sardis and Susa, several other roads could allow a traveler to go from India to Egypt (Briant, 2002).

Although the Persian road system was far more extensive than that of their Egyptian and Assyrian predecessors, it was still primitive by modern standards. The roads are described in Greek accounts as hamaxitos or “wheel worthy,” which means they were wide enough to accommodate chariots and carts. The roads could become unusable if there were too much rain, but water itself was not a barrier. Herodotus noted in his Histories (1.186) how there was at least one bridge that crossed the Euphrates River in Babylon before the Achaemenid Persians arrived.

All Roads Lead to Rome

Geography played a major role in the lack of significant road building in classical Greece. Because Greece is a land of islands, peninsulas, and archipelagos, the ancient Greek states were Thalassocracies like their Near Eastern predecessors and contemporaries. The Romans, on the other hand, developed Europe’s first complex road system.

Influenced by the Etruscans before them, the Romans built a number of roads throughout northern Italy during the Republic. Beginning about 300 BCE, they built upon this nascent transportation system by concentrating a series of roads, known as “vias,” that emanated from Rome (Sitwell, 1981). This was the origin of the term “all roads lead to Rome.” The Roman road system was just as extensive as the Achaemenid Persian system, and it was much better built and, therefore, more enduring.

Roman roads were more durable than Persian roads because they employed a combination of cement, stone, and rubble in several layers. The roads varied in width from three feet to 23 feet, with the wider roads located in more populated areas. The roads were originally built by and for the military. Professional engineers would survey routes, develop plans for bridges, and oversee construction. Once the roads were completed, the public was free to use them and local communities were generally responsible for maintenance.

The Appian Way: Queen of Roads

Among the greatest and most important of all Roman roads was the so-called “Queen of Roads,” the Appian Way. The Appian Way was named after the Roman statesman Appius Claudius Caecus (c. 312-279 BCE), the censor who was credited for the project. Construction on the Appian Way began in 312 BCE with the idea of connecting Rome to Capua in the south. The road was intended to develop the economically underdeveloped southern part of Italy. Before the Appian Way, the region around Capua was almost exclusively agrarian, but Appius hoped to transform the area into one where commerce played an equal role (Staveley, 1959).

It is notable that not long after the Appian Way was built, the silver denarius, Rome’s standard coin currency, was first produced. The Roman Republic became the premier military and economic power in the western Mediterranean thanks to its road network. Commodities could be relatively easily exported along the Roman system alongside legions who were constantly expanding Rome’s borders.

Many notable events occurred along the Appian Way during the Republic and Empire (Hamblin and Grunsfield, 1974). The Queen of Roads was witness to battles during the Pyrrhic War (280-275 BCE), the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE), and the Third Servile War (73-71 BCE). The Appian Way also played a role in the development of early Christianity. According to Christian tradition, the Apostle Peter left Rome on the Appian Way. Peter then turned back north before he was captured by Roman soldiers and ordered to be crucified by the emperor Nero.

The First Silk Road

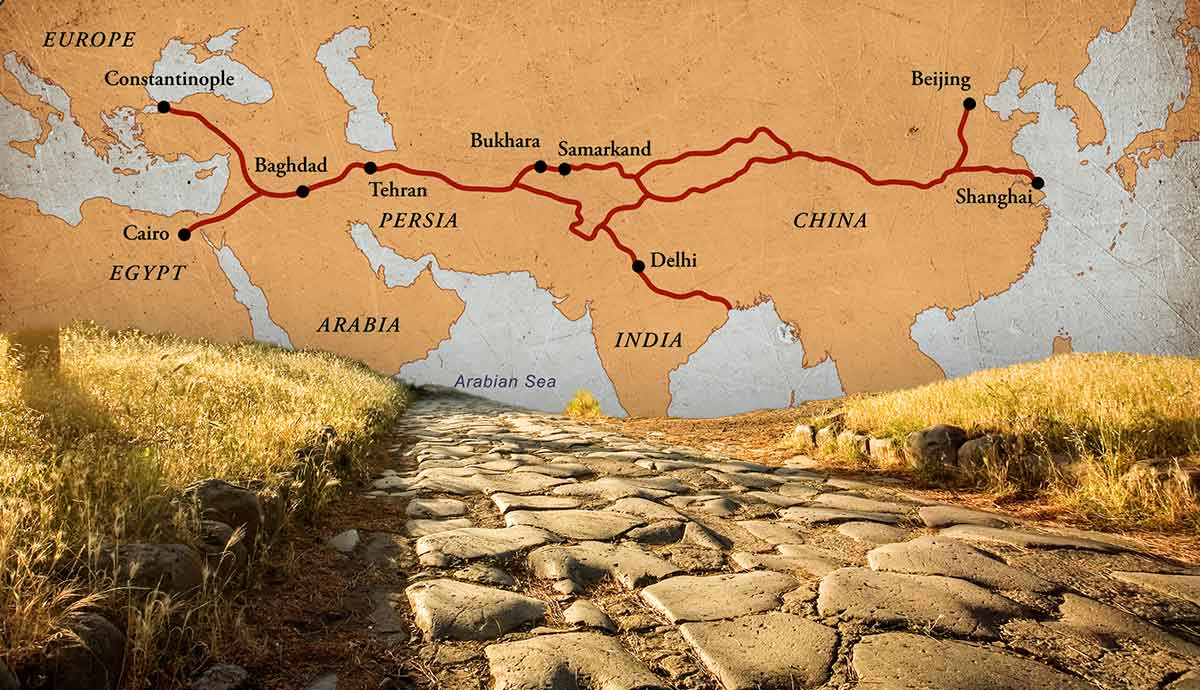

One final notable ancient road system worth mentioning is the First Silk Road. Although the Silk Road is generally considered a medieval system, the first iteration was created from the late 2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE. The First Silk Road was actually a number of different routes that connected Han China, Parthian Persia, the Kushan Empire, and Rome (Benjamin, 2018).

Some of the routes were partially sea-based, though they connected with land routes. Many of the overland routes in the Near East were even upon the same paths as the Achaemenid and Assyrian roads. The routes of the Silk Road were primitive when compared to Roman roads, yet they proved to be effective conduits for trade and ideas. In particular, Buddhism, Christianity, and Islam made their way with monks and pilgrims along the Silk Road as they proselytized in new lands.

Ancient people built roads out of necessity to facilitate the movement of troops and trade. Eventually, though, as governments grew and technology improved, so did roads. Road networks became more expansive, and the roads themselves became more stable and enduring. Eventually, ancient roads were used to transport ideas as much as material goods, providing a template for how roads have been utilized since.

Selected Bibliography

Benjamin, C. (2018) Empires of Ancient Eurasia: The First Silk Roads Era, 100 BCE-250 CE, Cambridge University Press.

Briant, P. (2002) From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire, Eisenbrauns.

Gardiner, A.H. (1920) “The Ancient Military Road between Egypt and Palestine,” The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 6.2: 99-116.

Haywood, J. (ed.) (2004) The Penguin Historical Atlas of Ancient Civilizations, Penguin Books.

Hamblin, D.J. and Grunsfeld, M.J. (1974) The Appian Way: A Journey, Random House.

Redford, D.B. (1993) Egypt, Canaan, and Israel in Ancient Times, Princeton University Press.

Shaw, I. (ed.) (2004) An Oxford History of Ancient History, Oxford University Press.

Sitwell, N.H.H. (1981) Roman Roads of Europe, St. Martin’s Press.

Staveley, E.S. (1959) “The Political Aims of Appius Claudius Caecus,” Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 8.4: 410-433.

Van de Mieroop, M. (2024) A History of the Ancient Near East ca. 3000-323 BC, Wiley.