During the Middle Ages, Christian Europe was immersed in a totalizing culture of violent, oppressive antisemitism. In the Muslim world, however, life looked far different for Jewish communities. Throughout the centuries of the Islamic Golden Age, peaceful and prosperous coexistence between Muslims and Jews was the norm. What did that coexistence look like? Keep reading to find out.

What Was the Islamic Golden Age?

The periodization of the Islamic Golden Age varies. Some place it in the period from roughly 750 CE until 1258 CE, from the founding of the Islamic Abbasid Dynasty until the destruction of the Baghdad House of Wisdom. Others argue for a wider conception, starting as early as the 500s CE and ending as late as the 1500s CE. For the purposes of this article, we will focus on the years 750-1238 CE, the most consistent and significant period of flourishing throughout the Islamic world.

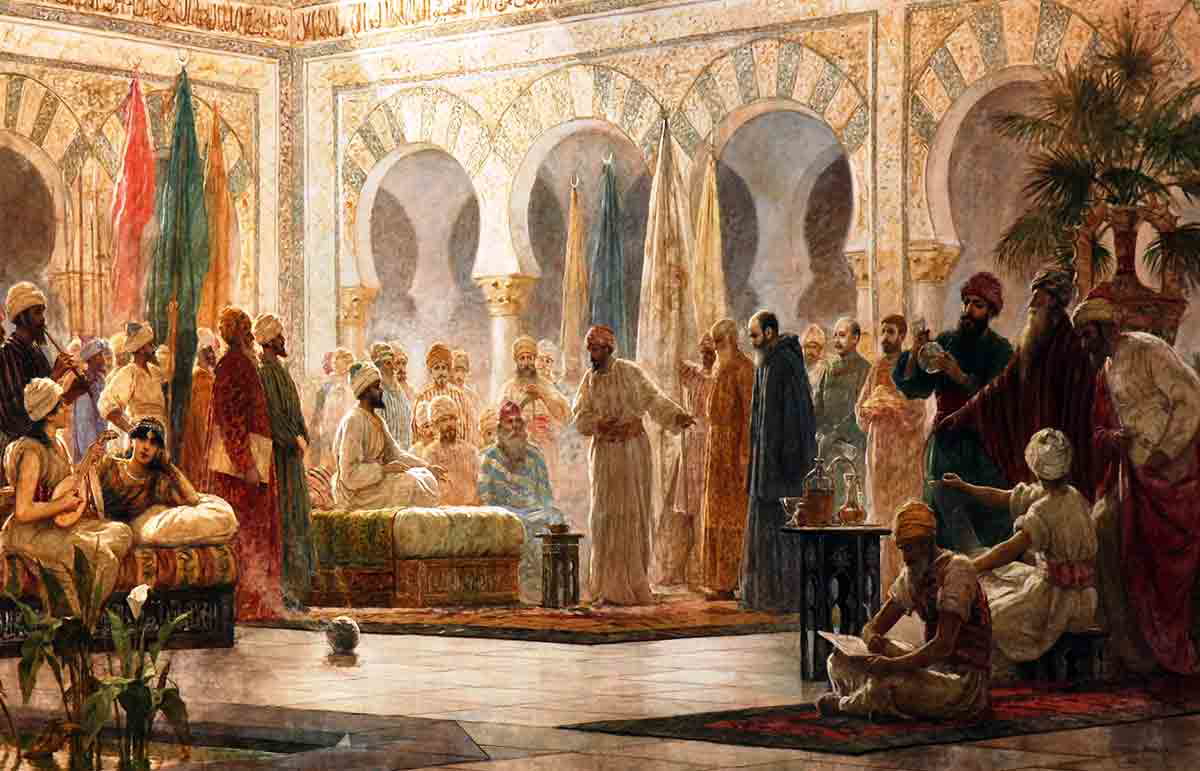

The Muslim world at its height was massive. It spread throughout much of the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain, across several different dynasties — the Abbasid Dynasty, centered in Baghdad, the Fatimid Dynasty, centered in Cairo, and the Umayyad Dynasty, centered in Cordoba. Each dynasty was ruled over by an Islamic religious and political leader known as a Caliph.

The Islamic Golden Age was characterized by the importance placed on learning, leading to incredible achievements in the arts, sciences, and philosophy. With the great Baghdad House of Wisdom as the locus of intellectual development, great strides were made in the realms of medicine, astronomy, mathematics, and so much more. Numerous forms of education were on offer, such as in schools, libraries, and observatories.

Governance during the Islamic Golden Age was based on Islamic religious and juridical principles. Islamic scholars carefully studied religious texts such as the Qu’ran and the Hadiths to create the laws governing Islamic society. For instance, interest-free loans were provided for the poor, following Islamic principles condemning usury.

Politics in the Muslim world was guided by a religiously informed vision of peace and justice. Outside of specifically Islamic influences, the philosophical underpinnings of Islamic political and social life were based above all on Greek philosophy and science, as well as Persian and Indian thought.

Muslim imperial rule further allowed for a notable degree of cultural diversity within unity, distinguishing the Islamic world from the oppressive and suffocating Christian rule in Europe. The greater inclusivity of Muslim society was a central reason for the rapid advances made in the arts and sciences.

The Islamic Golden Age suffered a slow decline as a result of the Crusades, the Mongol invasions, and a number of other political and economic factors. Eventually, Christian Europeans seized many Muslim territories, oftentimes through brutal means.

Spain was conquered by the Christians at the end of the Spanish Reconquista in 1491. Amongst the Jewish communities forcefully expelled by newly Christianized Spain in 1492, a nostalgia for the much-preferable conditions of Muslim rule began to develop. This nostalgia was the original basis for the utopian conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age.

The Utopian Conception of Jewish-Muslim Relations

Modern historiographical studies of the lives of Jewish people during the Islamic Golden Age began in the early 19th century, led by the scholarship of Jewish historians. These scholars, living in the midst of horrific Western European antisemitism, dreamed of a world free of antisemitic violence and oppression. Taking cues from the previously expelled Jews of Spain, they found evidence that such a world is possible in their study of the Islamic Golden Age.

These historians envisioned the Islamic Golden Age as a sort of utopia for Jewish people, relative to the horrors of the Christian West. In the Islamic Golden Age, they saw a model for widespread Jewish flourishing.

According to these historians, the Muslim world during the Islamic Golden Age was uniquely tolerant of Jews and Jewish life as a whole. They cite the political and cultural achievements of Jews in the Muslim world, as well as evidence of widespread social integration, to make their point.

Following the popularization of Zionism among historians in the 20th century, especially among Jewish historians, there was a tremendous backlash to the utopian conception forwarded by the early historians. These 20th and 21st-century scholars argued for a highly pessimistic view of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age — the polar opposite of the utopian conception.

The Pessimistic Conception of Jewish-Muslim Relations

During the 20th century, Jewish-Muslim relations steadily declined under the pressure of mass Zionist immigration to Palestine. Violence broke out between Jews and Muslims throughout the Middle East. Indigenous Jewish communities, such as those in Yemen, were increasingly persecuted by Muslims. Zionist settlers in Palestine stopped integrating into pre-existing communities and engaged in increasingly intense violence against their new majority-Muslim neighbors.

In this context of ratcheting tensions between Jews and Muslims, some scholars began to argue for a pessimistic conception of Jewish life during the Islamic Golden Age. According to the pessimistic conception, Jewish life under Muslim rule was not unlike Jewish life under Christian rule: violently antisemitic and persecutory as a rule.

Unsurprisingly, there is some truth in both the utopian and pessimistic conceptions of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age. Both, however, err too far in one direction or another. So, what did the reality look like?

Jewish Legal Status During the Islamic Golden Age

Throughout the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish communities submitted to an overall condition of Muslim rule in exchange for protection against targeted persecution and oppression.

Jews were allowed general cultural and political freedom, within some limitations, which were largely the same as the limitations imposed upon Christians. Both Jews and Christians, as non-Muslim monotheists, were legally categorized as dhimmi, a special legal category literally meaning “protected person.” Dhimmi were not subject to forced conversion, following the principle of non-compulsion laid out in the Qur’an (Sura 2:256). They were socially and territorially mobile.

Unlike in the Christian world, dhimmi Jews were allowed to govern many of their own matters of religion, as well as family and personal matters, according to their own precepts. They could select many of their own leaders and jurists. For example, many Jewish communities maintained their own Rabbinical courts in order to adjudicate internal disputes.

Some of the limitations imposed upon all dhimmi included prohibitions against constructing new religious sites, bans on public engagement in religious rituals, wearing clothing differentiating them from Muslims, and acknowledging Muslim rule. In these senses, Jews were discriminated against by the Muslim world, as were other dhimmi.

However, these discriminatory practices did not amount to active, targeted persecution of the kind practiced throughout the Christian West. As other dhimmi were discriminated against in a similar manner, there was no specifically anti-Jewish intent behind the discrimination. Moreover, restrictions placed upon Jews were often ignored by local Muslim rulers. So long as Jewish communities did their duty as dhimmi, above all by paying special poll taxes and accepting Muslim superiority, many of the restrictions placed upon them were often relaxed.

Jewish Intellectual and Cultural Life During the Islamic Golden Age

The mobility of Jews in the Islamic world created ideal conditions for the dissemination of Jewish culture on a much wider scale than seen anywhere else. Jewish communities could share cultural developments, exchange goods, and teach each other about unique beliefs and practices.

Jews were increasingly urban throughout the Islamic Golden Age, with many moving to Baghdad. In Baghdad, two great rabbinic academies were established under Muslim rule as the centers of Jewish intellectual life. Jews from all throughout the Muslim world learned at the academies. Thousands of letters the academies sent to Jewish communities—from the Mediterranean to North Africa to Spain—are preserved to this day. The letters instructed Jewish communities on important matters of law and practice.

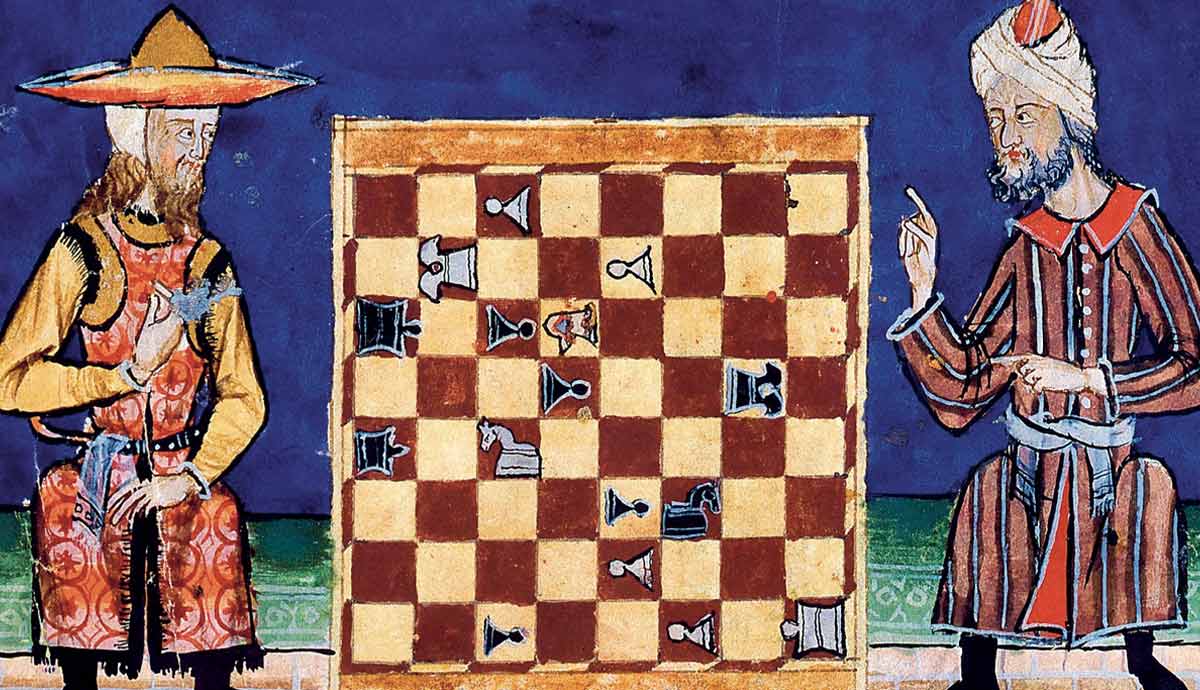

Jews and Muslims commonly inhabited the same public spaces and lived side-by-side in harmony. Cross-cultural pollination between Jews and Muslims enriched the intellectual and cultural traditions of both. Jews in Baghdad, as well as other cosmopolitan centers of learning, such as Cordoba, worked in close conversation with their Muslim peers to advance the arts and sciences. Jewish thinkers developed everything from medicine to linguistics to poetry.

They read and wrote in both Arabic and Hebrew, maintaining their own cultural tradition while not segregating themselves from the Muslim world around them. Arabic texts were frequently translated into Hebrew and vice-versa. For instance, the famed Jewish philosopher Maimonides was highly successful in Muslim Spain. He engaged heavily with both Hebrew and Arabic texts during his philosophical career. Thinkers such as Maimonides were accepted and honored by their Muslim peers.

Jewish Economic Life During the Islamic Golden Age

Jews in the Muslim world were full participants in economic life. They were allowed to engage in economic activities with few restrictions, in stark contrast to the Jews of Christian Europe. They commonly worked with Muslims and other non-Jews as equals, in a variety of industries.

During the peak of the Islamic Golden Age, Jewish traders and merchants became heavily involved in economic life, especially in the great city of Baghdad. They were further integrated into the court of the Abbasid Dynasty in Baghdad, playing significant roles in commerce and economic administration.

Other Jewish communities earned their livelihoods as everything from craftsmen to physicians to farmers to pharmacists. Many Jewish craftsmen were especially successful, producing goods for Muslims and non-Muslims alike.

Jewish-Muslim economic integration helped Jewish communities maintain positive, mutually beneficial connections with Muslims. It allowed individual Jews to hold significant positions of power throughout the Muslim world and to access the wealth needed to live well.

Jewish-Muslim Conflict During the Islamic Golden Age

Jewish subjects of Muslim rule were rarely singled out and targeted by Muslims specifically as Jews. Most of the conflict between Jews and their Muslim sovereigns and neighbors resulted from Jews’ status as dhimmi.

Some Muslims were suspicious of dhimmi. While dhimmi were far preferable to polytheists in the eyes of Islam, they still believed in corrupted versions of the truth and failed to accept the authority of the Prophet Muhammad. These facts led to varying degrees of distrust of dhimmi motives and actions among Muslims. However, this low-level interpersonal conflict was not universal and did not result in systematic persecution or oppression.

Throughout the Islamic Golden Age, some individual Caliphs imposed limitations on Jews and other dhimmi participants in political life. Typically, these Caliphs attempted to unilaterally remove some or all dhimmi from public office. However, dhimmi were too critical to the successful administration of imperial power to be removed from all public offices, and they held significant positions of power throughout the Islamic Golden Age.

Episodes of large-scale violence against Jews were exceedingly rare, but not unheard of. One 11th-century Muslim ruler, the Fatimid Caliph al-Hakim, destroyed a number of Jewish religious buildings and forcefully converted Jews in Egypt and Palestine to Islam. Another, lesser Muslim ruler attacked Jewish communities in Spain and North Africa before forcefully converting their inhabitants. Although these horrific episodes seriously harmed Jewish communities, they were not provoked by specifically anti-Jewish sentiment. Both also targeted Christians. Most infamously, Caliph al-Hakim ordered the total destruction of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre and other Christian religious sites alongside Jewish ones.

The most infamous occasion of Muslim persecution of Jews during the Islamic Golden Age was the Grenada massacre of 1066 CE. The massacre was instigated when an ambitious Jewish high official was accused of trying to overthrow the Muslim government in Granada from within. Other Grenadan Jews were suspected of being involved in the official’s plot.

One afternoon, after the accusation was made in public, a crowd of Muslims gathered together at the official’s home. They murdered the official, then marched through the streets killing Jews and destroying Jewish property. Anti-Jewish riots and massacres sporadically occurred under similar circumstances elsewhere in the Muslim world.

However, these outbursts of anti-Jewish violence and persecution were the exception, not the rule. The utopian conception of Jewish-Muslim relations during the Islamic Golden Age is an exaggeration, but it gets far closer to reality than the pessimistic conception. Jewish-Muslim relations throughout the Islamic Golden Age were overwhelmingly characterized by peaceful and prosperous co-existence within a culture of mutual acceptance and appreciation.