In 1429, a French village girl started experiencing strange visions of saints and angels. They told her that she had to lead the French army to defeat the enemy that had been tearing her land apart for almost a century. The girl’s name was Jean of Arc. Over the centuries since her execution in 1431, Joan of Arc became a symbol of many different concepts—from French patriotism and religious piety to feminist causes and the latest fashions. Read on to learn more about the evolution of Joan of Arc’s image.

1. The Only Image of Joan of Arc From Her Lifetime

The case of Joan of Arc is a remarkable one in Medieval history. Not a single character from that long and eventful era left behind such a vast amount of written sources and mentions. During the Hundred Years’ War, the English monarch, who considered himself the heir to the French throne as well, successfully conquered French territories. The city of Orleans stood in the way of the English army on its way to southern France, but it had limited resources and could not contain the enemy for too long.

In 1429, an unknown woman appeared in Orleans, claiming she had come to save her country. Her name was Joan of Arc, and she was only seventeen years old. Initially suspected to be an English spy, she somehow managed to become the leader of the French army. Soon, she managed to fight off the attack on Orleans and even move forward, freeing some of the occupied territories.

Soon after the unsuccessful siege of Paris, Joan of Arc’s influence almost dissolved. In 1430, she was taken prisoner by the Burgundian allies of the English and soon burnt at the stake on the accusations of public heresy. Formally, the reason for such conviction was Joan’s supposed demonic visions and her preference for wearing men’s clothing. In reality, however, this was mostly a political move aimed at eradicating an influential and powerful figure from the enemy’s side. The only image of Joan of Arc made in her lifetime was a 1429 sketch on the margins of a Parisian parliamentary document. The clerk who drew the portrait never actually met Joan and depicted her with long hair and wearing a dress, contrary to historical evidence.

2. Peter Paul Rubens, 1620

After Joan of Arc’s execution, the memory of her disappeared from written and artistic sources for several decades. The reason for that was her questionable status: no one could tell if she was an ambitious opportunist, a delirious village girl with strange visions, or, indeed, a savior sent to France by God. In 1456, the post-mortem public trial clarified her status, clearing her of heresy charges and announcing her as a god-fearing prophet compared to Jesus Christ.

In the 17th century, during the life of Peter Paul Rubens, Joan of Arc was rarely mentioned in official historical records. In the Early Modern paradigms, history was written by monarchs only and had no place for common people. Still, she often appeared in various publications on famous Frenchmen. The perception of her image suddenly transformed: from a timid, god-fearing Christian girl, she became an active patriotic hero indifferent to traditional womanly duties, willing to destroy every enemy of her land. Instead of Medieval saints, writers and artists compared her to the goddesses of Greek and Roman Antiquity and Amazon queens. The image became more militaristic, reflected in the 1920 painting by Rubens.

3. Pierre Revoil, 1819

The French Revolution once again transformed Joan of Arc in the public view, and not in a favorable sense. Her heroic act became associated not with defending one’s land but with being loyal to the French monarchy. For several decades, the cult of Joan and the calls for her canonization became associated with the outdated social order and the crimes committed by the crown. Pro-revolutionary crowds attacked sculptures of Joan and even called for her complete eradication from history.

It all changed once again in the first half of the 19th century. Jean of Arc returned to art and literature soon after Napoleon came to power. Napoleonic propaganda utilized her image in a secular fashion, representing the heroine not as a saint but as a fearless and honest soldier.

4. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, 1854

Despite four hundred years passing, the true height of Joan of Arc’s visual cult happened in the 19th century. Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, like many other popular artists, ignored the historical evidence of the heroine’s appearance. Painted with long hair, a feminine figure enhanced by strangely shaped armor, and even a long modest skirt that covered her legs, she had little to nothing in common with the real character.

The most remarkable part of Ingres’ work, however, was not the long list of historical inaccuracies but the halo painted around Joan’s head. The canonization of Joan of Arc was a long-standing question, raised for the first time in the mid-fifteenth century. Still, the issue has not been resolved during the artist’s time. Ingres’ commissioner was concerned with the secularization of Joan’s image and deliberately asked to highlight her religious significance.

5. Jules Bastien-Lepage, 1879

Jules Bastien-Lepage was a French painter from Lorraine, the territory annexed by the Germans following the Franco-Prussian War in 1870. Joan of Arc, who was born in Lorraine as well, once again became a national symbol, this time with a deeply tragic undertone. Bastien-Lepage took a step aside from the heroine’s military pursuits and focused on her mystical experience. He painted her barefoot, dressed in simple clothing, standing in her parents’ garden at the moment of a great spiritual revelation. The supposed naturalism of the scene was ruined by the figures of saints and angels hovering behind her.

6. Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1882

Joan of Arc became a popular character among the artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Dante Gabriel Rossetti and John Everett Millais painted the heroine several times, adding her to the gallery of Pre-Raphaelite women, identical in their fairy-like beauty. Previously, in England, Joan of Arc was the subject of ridicule or bitter parody as a military figure representing the long-term enemy. This time, however, her aestheticized devotion became the most remarkable of her traits. Her purity and tragic fate put her into the Pre-Raphaelite canon next to Shakespearian Ophelia and Elizabeth Siddall.

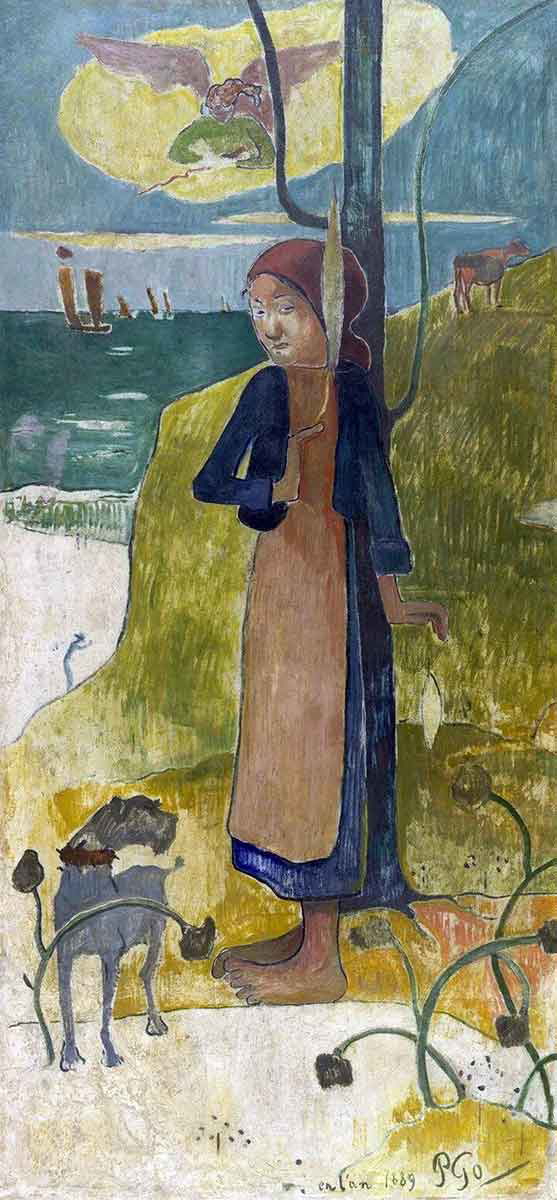

7. Paul Gauguin, 1889

Paul Gauguin was hardly ever interested in history painting, but sometimes he reinterpreted and reinvented religious scenes and figures. This was common for the period he spent in Brittany at the height of his career. For him, Brittany was another exotic location similar to Tahiti. There, Christianity blended with remnants of Celtic paganism. One of the paintings of this period featured a young Breton girl in a traditional dress spinning wool and watching over a cow. An angel with a sword is hovering above her, hinting at the possibility of an average village girl becoming a legendary warrior. The painting was accidentally discovered on a hotel wall under layers of wallpaper in the 1920s. In an 1889 letter to Vincent van Gogh, Gauguin stated he decorated the hotel’s dining room with murals, testing an unfamiliar technique.

8. Albert Lynch, 1903

Perhaps one of the most famous images of Joan of Arc was most likely the closest in terms of historical accuracy. Albert Lynch was a French-Peruvian artist known for his gentle pastel portraits of women. His Joan of Arc was hardly less feminine than in previous artworks, but at least Lynch painted her hair short and dark in accordance with historical testimony. Little is known about the artwork’s origins except that its most famous copy was the engraving published on the cover of the 1903 Figaro Illustré magazine. The original work quickly moved to a private collection and is rarely accessible to wider audiences.

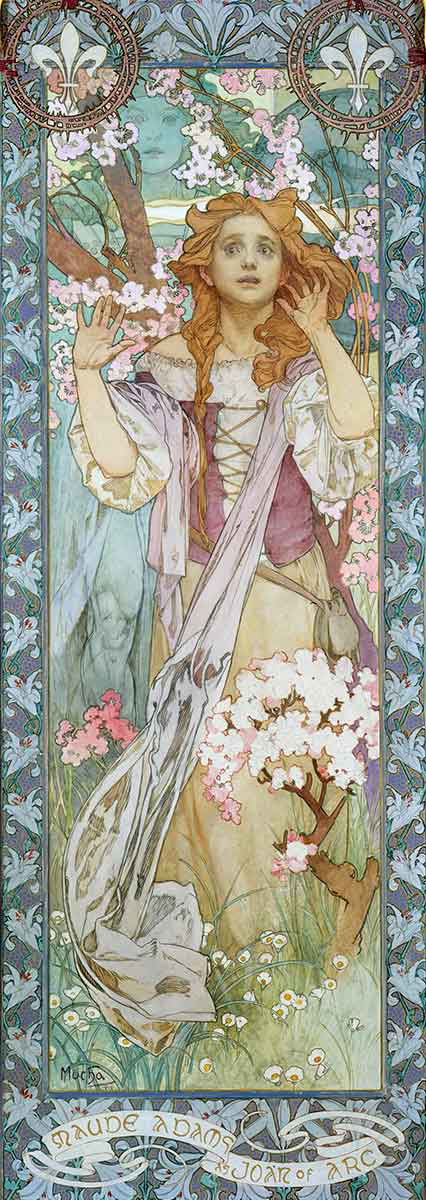

9. Joan of Arc by Alphonse Mucha, 1909

By the beginning of the 20th century, Joan of Arc turned from a political and religious figure into a pop culture character from dramatic plays, films, and advertisements. In 1909, the legendary illustrator Alphonse Mucha designed a poster for a one-time performance of a famous actress called Maude Adams in the tragedy The Maid of Orleans by Friedrich Schiller. Even though Adams was known for her gender-ambiguous roles, Mucha painted her distinctively feminine, surrounded by flowers.

In 1920, Joan of Arc was finally declared a saint. The main motivation for it was World War I, during which her image became once again associated with patriotism, put on propaganda posters and advertisements. Apart from her wartime significance, Joan of Arc gained a surprising group of followers: women who fought for their right to wear their hair short. In 1920s Europe, short hair was considered a marker of depravity and loss of morals. Priests condemned women falling victim to fashion, and fathers locked up their daughters until their hair grew long enough to save them from shame. These women saw Joan of Arc, with her page haircut, as the symbol of women’s liberation and equal opportunities.