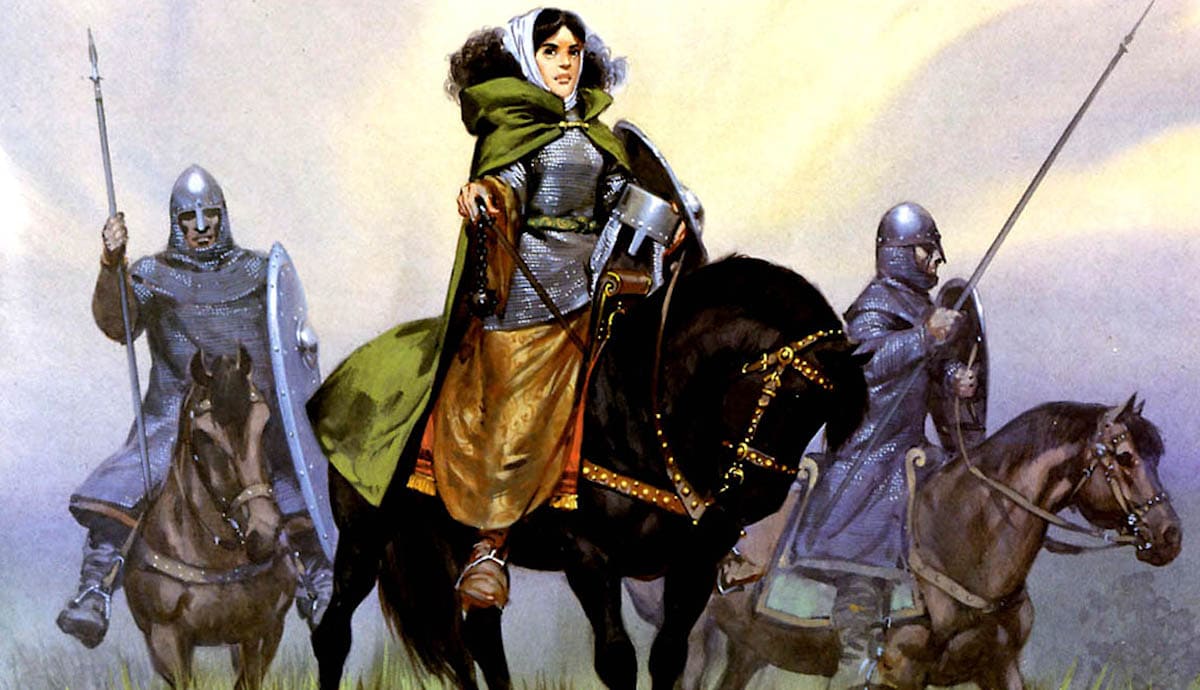

Throughout the Medieval Period (c. 500 CE – 1500 CE), crises, disasters, and war periodically shook societies to their core. When the bonds of feudal power loosened, medieval women frequently seized the opportunity to shed the patriarchal shackles placed upon them. Joan of Arc is the most famous — her transgressive role subverted the gender expectations of her day, which was the prime motivation behind her execution. Here are five more of the fiercest medieval women who led armies.

1. Military Medieval Women: Matilda of Tuscany

The Holy Roman Empire in the mid-11th-century was riven with religious strife, known as the Investiture Controversy. The Holy Roman Emperor and the Pope were at loggerheads over who had the right to appoint bishops and abbots. This was not some mere ecumenical matter — the holdings of the Church were enormous and wealthy, and so bishoprics wielded a huge amount of political power. Some even began to question whether the holy tradition of the Pope crowning the Emperor should be reversed, so that the Pope served the pleasure of the Emperor…

Amidst these religious wars, a teenage girl became the sole heir to the powerful Margraviate of Tuscany, after the assassination of her father, and the suspicious death of her brother. She was to become Matilda of Tuscany, known as ‘La Gran Contessa’ (the Great Countess) — and she would be pivotal in resolving the Controversy once and for all.

Even before she became a ruler in her own right, Matilda of Tuscany made it clear that she would not be governed, repudiating her husband in a marriage arranged by her regent mother — despite the opposition of the Pope. Within two months of each other, Matilda’s mother and her estranged husband had died. Instead of following the Salic law of the time (legally, all of her lands should have passed to Emperor Henry IV), Matilda laid claim to both her own ancestral lands and her husband’s!

Matilda of Tuscany was pitched headlong into the top flight of Holy Roman politics, and she rapidly became one of the Pope’s closest allies. This disgusted the Pope’s enemies, who lodged charges that the Pope had entertained a woman at his table, refusing to even name Matilda of Tuscany. This shows the depths to which powerful medieval women were reviled by their male contemporaries. Matilda’s smart advice (and her powerful army, which she led personally in the field) forced Emperor Henry IV to prostrate himself before the Emperor, walking barefoot in the snow to her castle at Canossa to entreat the Pope for reconciliation. She was only 31!

But this peace would not last. For the next two decades, Matilda would prove herself to be a formidable military leader, frequently donning armor to lead her troops in battle against Henry IV, and for the Pope. By the 1110s, she was the most powerful ruler in Italy besides the Pope, holding a sprawling domain which patronized hundreds of churches, hospitals, and monasteries. Her money was critical in building the famous Cathedral at Pisa. She is today one of only six women buried in the Vatican.

2. Margaret of Anjou

Another strong medieval woman who led several armies was the Lancastrian matriarch, Margaret of Anjou, who contended for the throne of England during the Wars of the Roses. She was the wife of King Henry VI of England, who was a troubled monarch. Beset by mental illness, Henry would frequently lapse into long periods of incapacity, what we would probably describe nowadays as acute depression.

This was an enormous problem for a centralized feudal state like 15th century England, which required the King to be proactive and involved in everyday government — everything that Henry was not. By contrast, Margaret was an extremely adept politician. Richard, Duke of York was the King’s closest male relative and he clearly had long-term designs upon the throne. He was appointed Protector during one of Henry’s bouts of incapacity — a serious threat to Margaret and (she believed), Henry. The country was on the path to war.

Initially, Margaret outmaneuvered Richard, excluding him from the King’s Council and having him stripped of his title of Protector. But Richard was prepared to play his entire hand — he captured Henry IV at the Battle of St. Albans in 1455, installing himself as ruler and leaving Margaret as the sole leader of the royal faction (called the Lancastrians, after Henry’s ancestral House of Lancaster).

Though Richard was actually killed in battle at Wakefield by one of her generals, Margaret frequently assumed command of the Lancastrian forces herself — and she led the Lancastrian army to victory personally at the Second Battle of St Albans in 1461. However, her luck did not last. The Lancastrians were beaten at Towton, and Margaret was forced into exile with her son Edward of Westminster, the last hope she had for regaining the throne. She consistently pursued the restoration of the Lancastrians, re-invading England in 1471 from France at the head of a new army, but her forces were beaten at Tewkesbury, and her son was killed in the battle. Now utterly defeated, she lived out her remaining years as a charity case in the courts of France, dying landless and penniless in 1482.

Margaret’s story is one of overwhelming perseverance in the face of enormous odds — which earns her a place amongst the fiercest medieval women.

3. Tomoe Gozen

The Japanese legend of Tomoe Gozen gives us another medieval woman who led armies. Although she exists on the margins of history, to the extent that many scholars dispute whether she is a historical figure at all, her story is a powerful tale of loyalty and ruthlessness. If she was indeed real, Gozen was a member of the warrior class of samurai. Although they would later become a powerful ruling class in their own right, in the 13th-century samurai were roughly analogous in status to Western knights, warriors who owed their allegiance to specific feudal lords.

Whilst in Europe there was no tradition of medieval women warriors, with knighthoods reserved solely for men, in Japan, the tradition of onna-musha saw female members of the samurai class trained in the use of weaponry alongside the men. Tomoe Gozen was likely not her real name. Tomoe means “patterned”, and likely refers to her armor, and gozen is a title reserved for honorable women. Nevertheless, the surviving literary canon which details her life refers to her as the daughter of Minamoto no Yoshinaka’s wet nurse. Lord Minamoto was a powerful clan general, and Tomoe Gozen quickly became one of his most trusted military leaders.

Tomoe was supposed to have led 800 samurai into battle. Where most onna-musha would fight with a curved naginata spear, she favored the katana sword, usually reserved only for men. Her exploits vary according to which source you choose but the consistent theme is that she was fearless in battle. One source describes her as “a match for a thousand warriors, and fit to meet either god or devil”, and several sources say that she defeated, captured, and ritually beheaded generals with much larger armies. The cultural impact of the legends told of her was significant; she is the subject of one of only 18 Noh plays about warriors, and the only one featuring a female warrior. In the 21st century, her legacy, along with modern archaeological evidence, has forced a re-appraisal of the role of medieval women in feudal Japanese warfare. Even hundreds of years later, she is still winning battles!

4. Lagertha

Much historical debate has swirled about the role of medieval women in Viking society. Traditionalists have always asserted that women, like in more southerly feudal societies, held a subordinate domestic role. But more and more evidence has emerged in recent years to challenge this view. It has long been accepted that there were powerful Viking queens who ruled in their own right, like Queen Åsa, who may well be one of the two women buried in the Oseberg Ship.

Recent DNA analysis has shown that the graves of many warriors, originally assumed to have contained the remains of male Vikings, in fact contain women — or, like the Suontaka burial, individuals who might have had more complex gender identities. As well, the persistence of “shield-maidens” in Viking mythological histories has led many to search for its foundational grain of truth. Frustratingly, many of these women warriors languish in the twilight of the Dark Ages, as we lack any historical confirmation — none more so than Lagertha, warrior-queen of legendary Viking King Ragnar Loðbrok.

According to the 13th-century Danish scholar Saxo Grammaticus, Lagertha was a kinswoman of Siward, a Norweigan King, who was forced into prostitution when the King of Sweden invaded and killed Siward. When Loðbrok set out to avenge the old King, the women took up arms and donned men’s clothing, fighting fiercely against the Swedes. Mightily impressed, Loðbrok wooed Lagertha, who bore him three children. Saxo writes elsewhere of Lagertha personally commanding 120 ships, driving off rebellious Danes with a counter-attack.

Lagertha’s story is beset with the many problems of Viking scholarship in general. The Christian scribe Saxo was writing of the distant pagan past partly from a genuine attempt to collate real history — but also with a definite moral standpoint. Christian writers of the era may well have been misogynistically satirizing the pagan waywardness of the Vikings (a woman military leader! Ridiculous!), who permitted ‘weak’ medieval women to rule them. Loðbrok himself remains a similarly unconfirmed figure — although several of the figures who claimed to be his sons are attested historical fact. If she existed, Lagertha remains just out of our grasp.

5. Khawla bint Al-Azwar

The last of our medieval women who commanded their own armies is Khawla bint Al-Azwar, one of the Companions of the Prophet Muhammad, and a serious contender for the title of the finest warrior woman in history.

The Arabian peninsula had been united under a single Islamic government under the Prophet Muhammad, but his death in 632 CE threw the project into uncertainty. Rather than lapsing, the Rashidun inheritors of the government in Medina launched a spectacular series of military campaigns, resulting in one of the largest empires in history in only 25 years. Khawla’s family were amongst the earliest converts to Islam — she is recorded as the daughter of the chief of the Banu Asad tribe, one of the peoples living in what is now Saudi Arabia during the first half of the 7th century CE. She learned sword fighting from her brother Dhirar, who was a member of the elite Mubarizun, who were champions that engaged in ritualized single combat. Khawla apparently didn’t get the memo about the “ritualized” or “single” bit, as she charged a Byzantine rearguard alone to rescue her brother at the Siege of Damascus (643 CE).

For much of her military career, she concealed her identity, fearing the prejudices of senior commanders — but in her ferocity and skill, she was frequently mistaken for Khalid ibn Walid, the general of the entire military campaign. Shurahbil ibn Hasana, commander of a Rashidun army, said of her “This warrior fights like Khalid ibn Walid, but I am sure he is not Khalid”. Like all of the medieval women we have examined here, Khawla bint Al-Azwar has left a lasting impact behind her, being commemorated as one of the leading warriors in early Islam — for example, the United Arab Emirates’ first female military staff training college is called the Khawlah bint Al Azwar Training College.

Medieval Women: Not to Be Trifled With

If the stories of the medieval women who commanded armies tell us anything, it’s that medieval women were infinitely more smart, resourceful, and brave than surviving patriarchal histories give them credit for. When the opportunity to become agents of their own destinies presented itself, medieval women wrested power away from broken systems and left their indelible stamp on history.