Summary

- The Last Great Pharaoh: Ramesses III (20th Dynasty) reigned for 30 years and was the last great pharaoh before an extended period of decline and foreign rule.

- Warrior King: He successfully defeated Libyan tribes and the Sea People to secure Egypt’s borders during the Bronze Age Collapse.

- Great Builder: Ramesses built a great mortuary temple for himself, Medinet Habu, and conducted a census of Egypt’s temples, restoring many.

Ramesses III was the second pharaoh of the 20th Dynasty during the New Kingdom, coming to power when Egypt was in a period of decline. During his roughly 30-year reign, he was able to slow this decline by defeating the Sea People and the Libyans, as well as pursuing an impressive building program. After his reign, the kingdom of Egypt fell into turmoil due to internal fighting and an inability to capitalize on the innovations of iron during the Iron Age. Following the death of Ramesses III, the New Kingdom slid into decline and foreign rule, which is why he is known as the last Great Pharaoh.

Ascension and Early Reign

Ramesses III (1184-1153 BCE) directly succeeded his father, Setnakhte (1186-1184 BCE), in the line of succession. Not much is known about Setnakhte, but he seemingly had no relation to at least the previous two Pharaohs. He may have been a usurper, perhaps related to the famous pharaoh Ramesses II the Great (1279-1213 BCE). Moreover, he only ruled for a maximum of three years.

The Ramesside Dynasty started successfully, but like the preceding 18th Dynasty of Akhenaten (1352-1336 BCE) and Tutankhamun (1336-1327 BCE), which fell apart, the 19th Dynasty fell to infighting. Like Horemheb (1323-1295 BCE) nearly a hundred years before him, Setnakhte, a military commander, took the crown, starting the 20th Dynasty. When Ramesses III succeeded his father, he consolidated his kingship by modeling himself on Ramesses the Great. He named his sons the same and gave them identical positions at court.

In year five of his reign, Ramesses III’s strength as a ruler would be tested. An amalgamation of Libyan tribes, including the Meshwesh and the Seped people, attacked Egypt. A similar conglomerate had attacked 25 years earlier during the reign of Merenptah (1213-1203) and was defeated. These Libyan tribes had been allowed to live in settlements at the western fringe of Egyptian territory in exchange for military service. They were now attempting to settle in the Nile Delta. Ramesses met the invading alliance and reported killing and circumcising 12,535 enemies and capturing 1,000 more.

The Sea People

Three years later, Egypt would have to defend itself again, and this time against a much greater adversary. When Ramesses III came to power, many coastal cities and old powers were suffering economic problems, natural disasters, and falling to a largely unknown foe. This period is now known as the Bronze Age Collapse. Ugarit, parts of Cyprus, the Mycenaeans, Palestine, and the Hittite empire had all been defeated by a group known as the Sea People, who fought both on land and at sea.

In year eight of Ramesses’ reign, the Sea People attacked on two fronts: one group moved by land toward the Delta from the northeast on their way from battles in Palestine, and the other moved via ships to the main mouth of the Nile. Ramesses prepared by issuing a nationwide conscription and sending these men to the mouth of the Nile, while the trained army met the Sea People at the Delta.

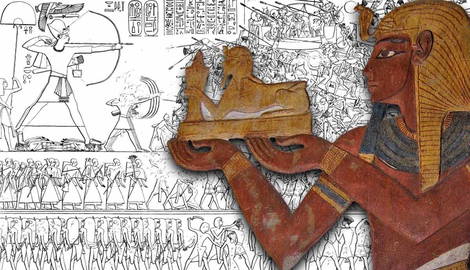

According to contemporary sources, Ramesses had archers positioned on shore, and naval warships met the Sea People in open water. The Sea People had ships designed to carry hordes of people, not fight at sea. Once the enemy ships were in range, arrows rained down on the Sea People. They seemingly tried to retreat away from the shoreline, only to meet the Egyptian ships. As the Egyptian armada was much better equipped for seafaring battle, the Sea People’s troop carriers were easily capsized, and hundreds drowned.

The land battle may not have been so successful. Interestingly, the sources simply state that the encounter was an Egyptian victory without details. Scholars typically cite this as evidence of heavy Egyptian losses.

Building Works

Ramesses then dealt with a larger uprising from the Libyan tribes, reportedly intercepting a horde of 16,000, killing 2,175 foes and capturing 2,052, as well as 43,000 animals, preventing the Libyans from settling in the Delta. With this threat put down, Ramesses III could turn his attention to construction projects.

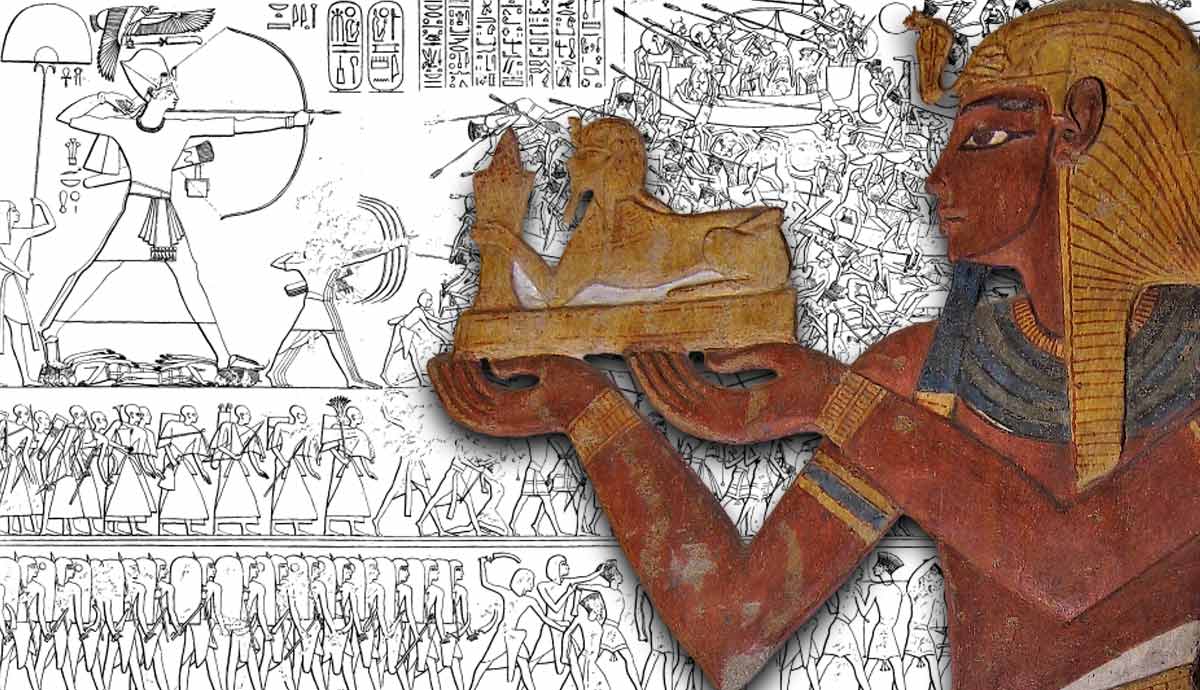

Ramesses III began construction on his mortuary temple, which was modeled after his great predecessor Ramesses the Great. The “Mansion of Millions of Years of Ramesses III, United with Eternity in the Estate of Amun,” or “Medinet Habu,” as it is known today, recorded many of the king’s achievements through great reliefs and carvings. In addition to extensive imagery showing his military successes, Ramesses had himself rendered in scenes of hunting and within the royal harem surrounded by women.

This magnificent work of architecture and art is also the last great monument of ancient Egypt. Later pharaohs chose to build smaller chapels on the site. Furthermore, the site was continuously occupied until the 9th century CE, with Coptic Christians erecting multiple churches within the mortuary temple.

Honoring the deities was arguably the most important role of the pharaoh in ancient Egypt. Ramesses adhered to this standard not only by constructing his own monuments but also by ordering an inspection of temples across Egypt. The way rites and rituals were performed was monitored and corrected to the Pharaoh’s standards. Moreover, the state of temples and their contents was recorded in intense detail, enabling restoration plans. The Luxor Temple was refurbished, the Temple of Seth in Nubt had a new shrine, and a new temple for Khonsu was constructed at Ipetsut.

Equally as impressive were Ramesses’ expeditions in search of foreign goods. He sent men to Sinai for turquoise, to Timna for copper, and to Punt for incense and myrrh. Punt was likely in modern-day Somalia, and trade with Punt had not been seen since the reign of Hatshepsut 300 years earlier. Ramesses was noticeably harking back to the glorious building programs and foreign exploits of the infamous 18th Dynasty.

Economic Turmoil and Unrest

However, Ramesses’ achievements were slightly undermined by economic instability. Unsurprisingly, fighting off foreign invasions was expensive, and as a result, the Egyptian treasury suffered. While temples were heavily stocked with exotic goods, the granaries were noticeably exhausted. Moreover, general commerce with the Near East was relatively poor since the Sea Peoples had sacked most trade centers.

Overt evidence of this economic turmoil manifested in what became the first recorded strikes in history. The necropolis workers of the Valley of the Kings received their wages, which also included their food, a month late. Temporary measures were put in place but were ultimately neglected due to preparations for the Pharaoh’s 30-year jubilee. The craftsmen, who lived in a specialist village called Deir el-Medina, received their next wages late and late again. They waited over two weeks before stopping work and marching to Ramesses’ mortuary temple and then orchestrating a sit-in at the temple of Thutmose III.

The strikes became bolder, with protests occurring at the Ramesseum, and even saw the workers preventing access to the Valley of the Kings. This meant mourners could not visit the deceased and maintain sacred rituals. It was apparent that local officials had no idea how to respond to the strikes and refused to tell the pharaoh, so as not to ruin the upcoming celebrations. The strikes were on and off for around three years before the officials could routinely pay the workers on time.

Although Ramesses was unaware of the strikes, they demonstrated the uncertainty of the economic state of Egypt during his reign. Likewise, the incidents exhibited the cracks growing within the government and failings within the organization of administration. Overall, the common people and local economies were overlooked to keep up appearances, as Ramesses was very conscious of the dwindling grain reserves.

Death and Conspiracy

The harem of the Egyptian pharaohs was a notable feature since at least the Old Kingdom. Female members of the kings’ families, as well as many wives and concubines, all lived together in a facility with its own administration. The harem essentially functioned as a second court with various political factions. After Ramesses’ jubilee in 1157 BCE, his deteriorating health was palpable to those within the harem and presented an opportunity to gain power.

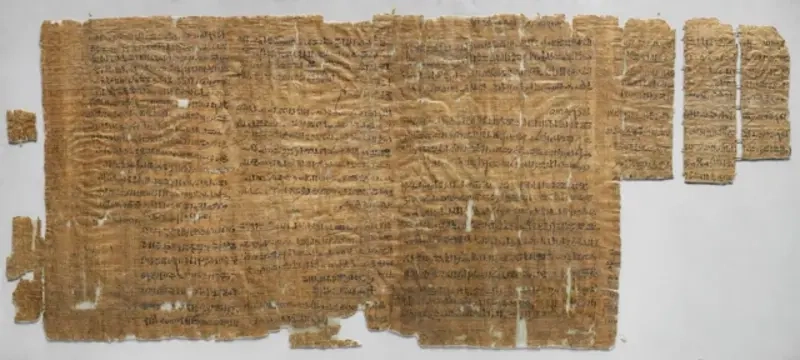

Thanks to the Judicial Papyrus of Turin, the transcripts from the trial of the harem conspiracy survive to the present day. A secondary wife of Ramesses, called Tiy or Tiye, conspired to have the pharaoh and his heir assassinated and her son, Pentaweret, installed on the throne. The plan was complex and involved multiple members of the harem and courtiers, including butlers, the Chief of the Royal Chamber, and the Head of the Treasury. One woman sent word to her brother, a military leader, to stage a mass mutiny to distract Ramesses. What ensued has been debated. It was long thought that Ramesses survived the attack, at least briefly, as the papyrus begins with him addressing the court. It states that he appointed twelve trusted officials to investigate.

However, further in the transcripts, Ramesses III is referred to as “The Great God,” a title only used for dead kings. While his mummy exhibited no obvious signs of assault, in 2011, the body was CT scanned, which revealed a wound on his neck going through to the bone; a wound that scientists stated was impossible to survive.

The 38 conspirators were found guilty. Some were forced to take their own lives, while others faced heavy mutilations for remaining silent on the affairs.

Legacy of Ramesses III

Ramesses III’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings (KV11) is one of the largest in existence and symbolic of his successes as pharaoh. His military victories, particularly against the Sea People, who destroyed many of Egypt’s contemporary states, were undoubtedly impressive despite potentially heavy losses. Additionally, his restoration of multiple religious centers and efforts to reinstate foreign trade displayed his attempts to strengthen Egypt after a period of instability.

Ramesses’ reign was not without its failings. Frequent wars set against an unpredictable political backdrop set the Egyptian kingdom up for economic turbulence. This economic instability continued throughout the reign of his son Ramesses IV (1153-1147BCE). Under his successor Ramesses V (1147-1143 BCE), raiding parties from Libya increased, and the pharaoh was ill-equipped to deal with the matter. The dynasty continued to decline until the death of Ramesses XI (1099-1069 BCE). Smendes (1069-1043 BCE) proclaimed himself pharaoh, but his weak position saw power increasingly shared with the powerful priests of Amun in Thebes, and then the rise of the Libyan dynasty (945-715 BCE).

Ramesses III’s son and successor had his father’s exploits detailed in the Great Harris Papyrus. This document is 41m long and the longest known papyrus from Egypt; an appropriate way to memorialize the Last Great Pharaoh.