The human brain, the most complex object known to us, has always been a source of fascination and mystery. Throughout our history of trying to understand it and ourselves, we have consistently relied on metaphors—often borrowed from contemporary technology and science—to grasp its intricate workings. Examining the use of metaphors in brain science reveals their profound influence on our understanding in positive and negative ways.

The Ever-Changing Metaphors of the Brain

Our comprehension of ourselves is inevitably shaped by what we know, even when it may not be related to reality. Like how technology and culture shape our fiction, our scientific explanations are also constrained by our current understanding. Descriptions of the world are not effective unless they are comprehensible. Metaphors, as simplification tools, are evident in our attempts to make sense of the complex brain and its induced behaviors.

This simplification is not intended for the layman; it is a tool for science, making objects and concepts graspable in their complexity so that tests and theories can be made.

The brain has always been an object out of the grasp of understanding, always shrouded in darkness, not illuminable by a cohesive explanation. This makes it the perfect target for the use of metaphors, an effective tool for trying to make sense of black boxes.

The Heart as a Brain

In ancient civilizations, the heart, with its central position and vital role in the body, was often considered the seat of the mind. While not a metaphor, this shows that what we understand and what makes the most sense based on current knowledge can easily be accepted as the truth, even without much evidence.

This idea was influenced by the heart’s intricate network and association with warmth and movement, the seeming properties of life. As air and water were the intuitive mediums for propagation, blood was a natural alternative for the propagation of thought and emotion. It shows that what is evident to us today couldn’t always have been so, and even lacking evidence, we try to create stories that make sense.

Even when experiments showed that the brain was the center of thought, it didn’t kill the continuation of this hydraulic metaphor for propagation, either centered around the heart, as believed by Aristotle, or the brain, based on the findings of the anatomist Galen.

Animal Spirits and Hydraulic Automata

Galen’s findings shaped another metaphor—that of animal spirits being in the ventricles of the brain and traveling through the blood. Similarly, this view had no evidence but simply made sense based on previous sensibilities and new observations of the brain’s anatomy.

The brain produced these animal spirits from vital spirits, which were generated from the heart and derived from food. These animal spirits then flowed through hollow nerves as messengers to carry out functions. While ludicrous today in its emphasis on the ancient Greek notion of humors and spirits, it is not that far off reality. This may have helped to propagate versions of it and its influence well into the 17th century.

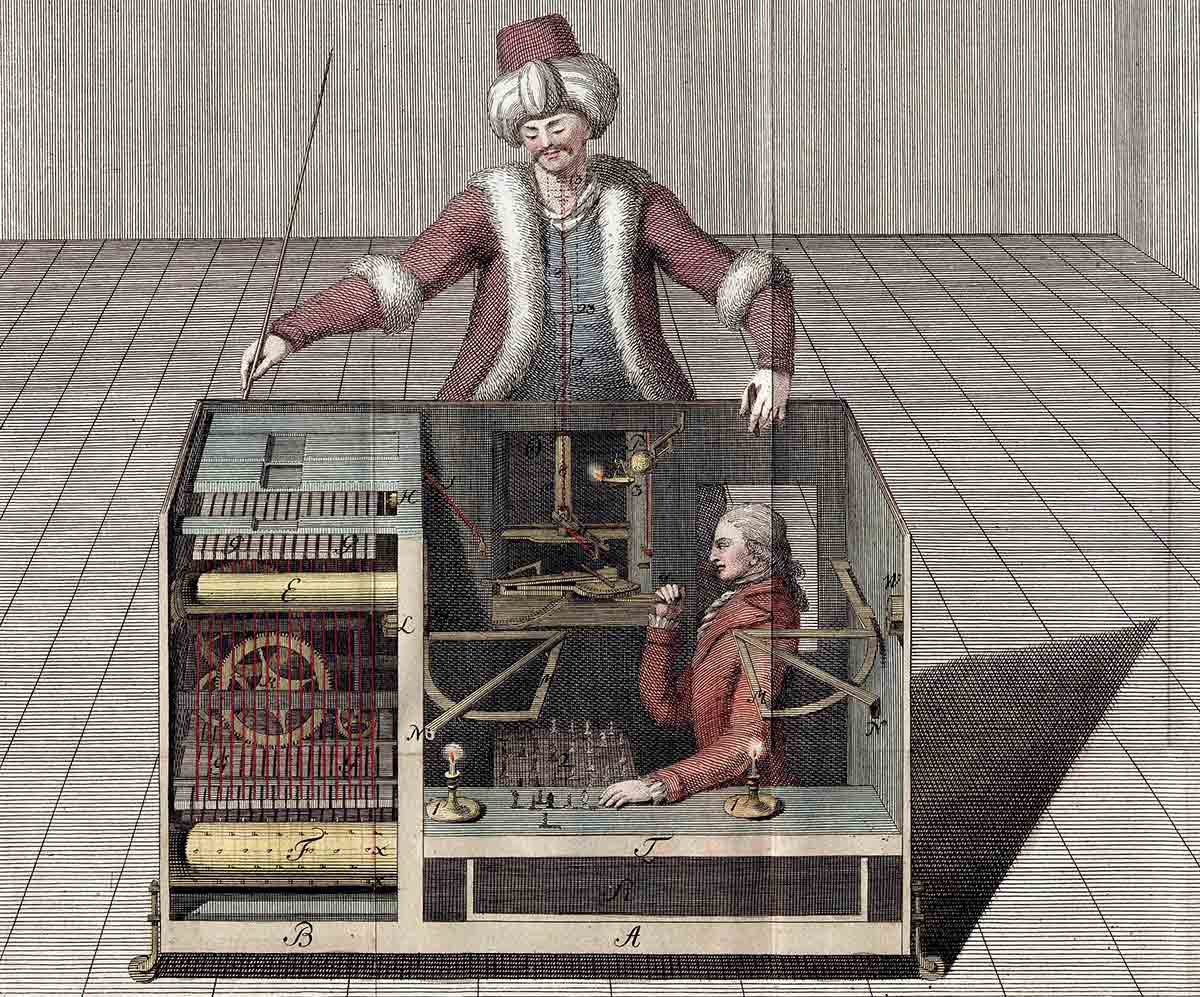

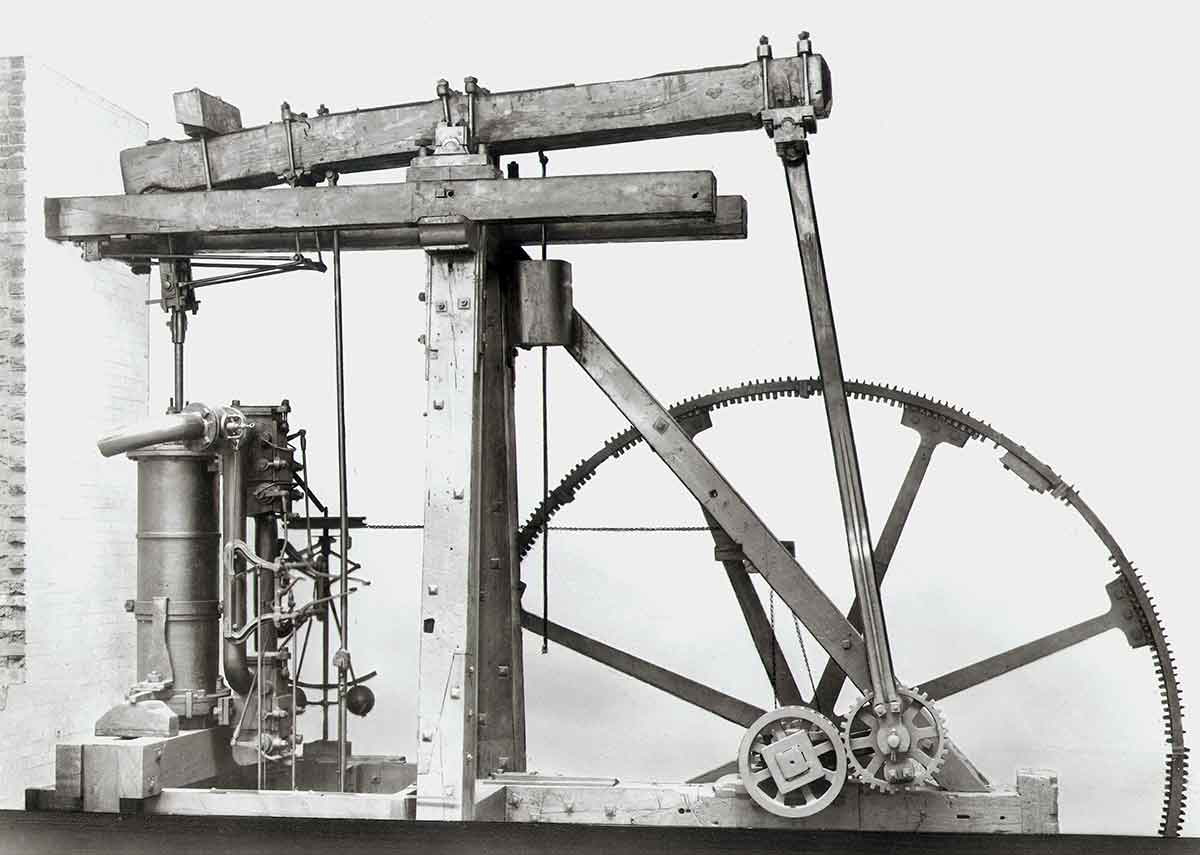

With advancements in anatomic knowledge and technology during the Renaissance, new and more precise metaphors emerged. Inspired by hydraulic automata, Descartes envisioned the brain as a system of fluid-filled pipes and valves, with the pineal gland as the control center between the material and immaterial. While more precise about the mechanisms, these ideas were as well evidenced as the previous ones, yet sensibilities, interpretations, and stories had changed.

The Brain as a Machine

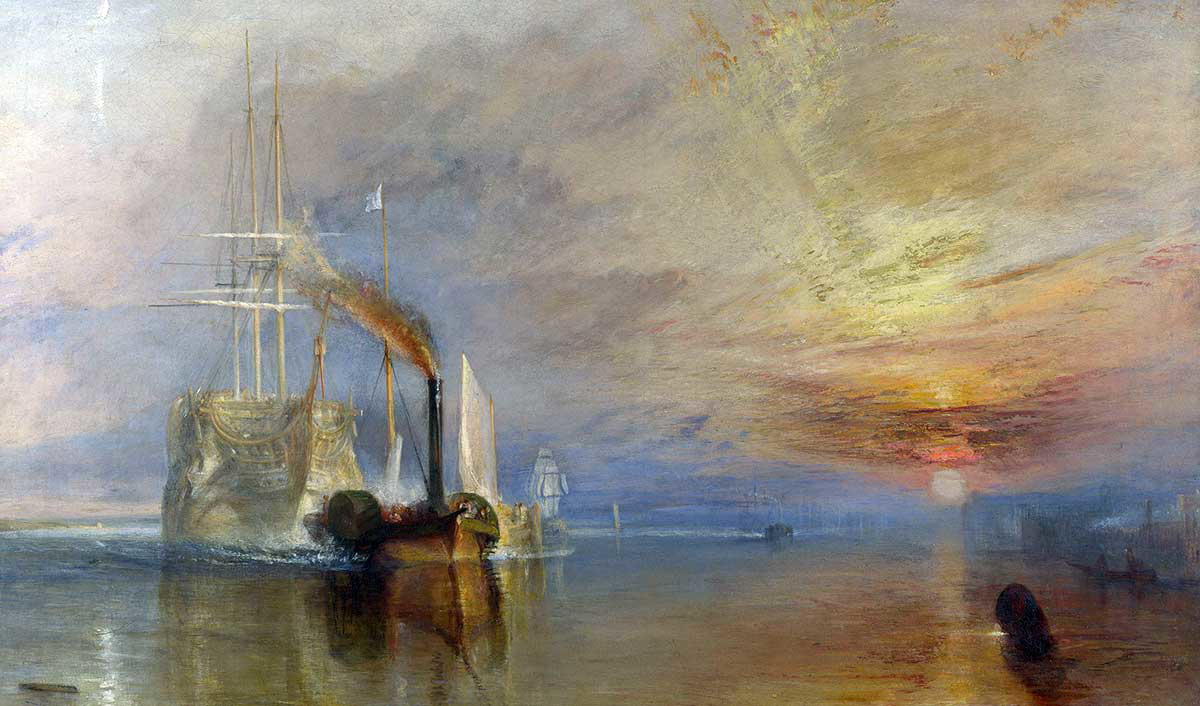

From the Industrial Revolution came an abundance of metaphors based on machines, like pistons, hydraulics, and clockwork. These metaphors shifted our perception towards a more material one, seemingly influenced by the complexity of the machines. Anatomical evidence and experiments disproved both Descartes’s view and the previous hydraulic one. Yet there was no replacement, so both proliferated thanks to their popularity and well-conceived stories.

The propagation replacement and its first explanation came through the commonplace occurrence of electricity. Electricity fits much better into nerve propagation, but it still couldn’t explain everything.

Information networks like the telegraph, with its network of wires transmitting signals, became powerful metaphors for the nervous system and how it is controlled. This metaphor evolved to that of the telephone switchboard system, with the brain imagined as the operator, controlling the inputs and outputs with cells as relay units.

With the start of our capacity to produce our complex machines and information networks, we started a faster evolution of our metaphors. Similarities and explanations could be made from these complex systems that we could understand.

The Computational Brain

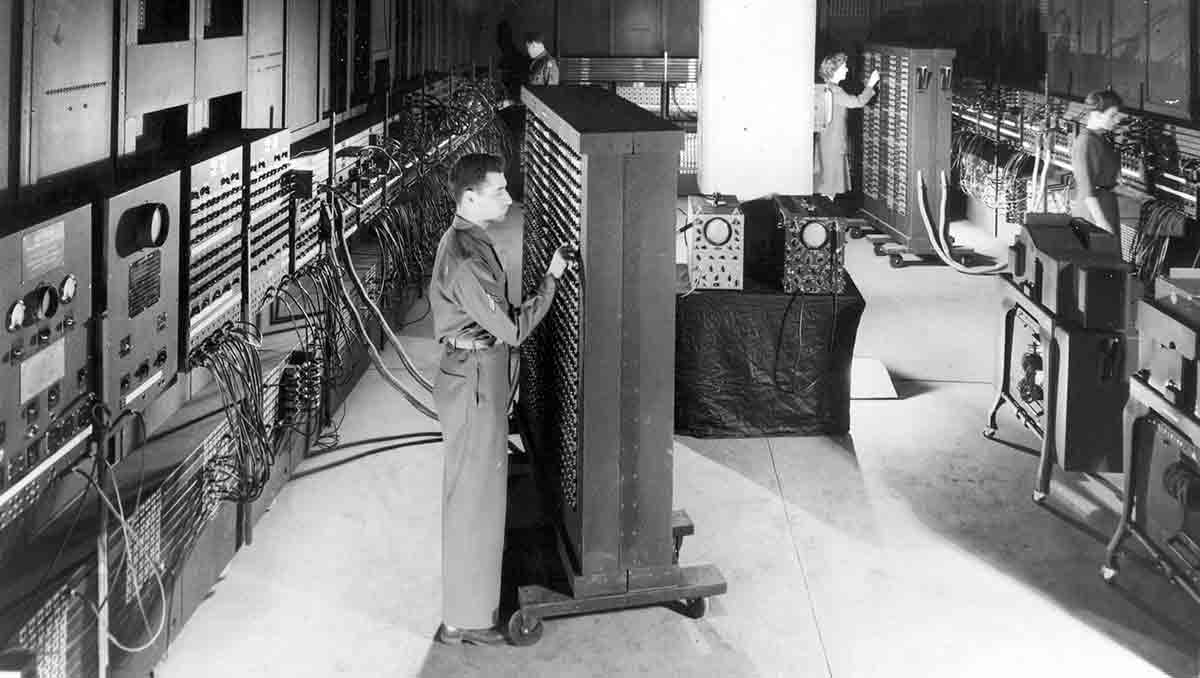

The advent of computers revolutionized our understanding of information processing, leading to the metaphor of the brain as a computational device. Even though the digital computer was first fashioned as a machine as a brain, this was later reversed, and the brain is seen as a computer, but the fact that it can go both ways shows its potency as a metaphor.

The digital computer is different from all the previous metaphors because it is a separate information processing system with components, electricity, and memory, together with the distinction between software and hardware. It gave a metaphor to explain the distinction between physical instantiation and mental. Even in the modern age, this metaphor has been incredibly pervasive, specifically in the fields that deal with this distinction, not neurology.

The field of cognitive science sprouted out from it, essentially taking the brain to be an information-processing machine just like the digital computer. It adopted symbolic computing and many of its concepts to try to explain what the brain does. It took brains to operate as programs and algorithms and assumed them to be computational and digital. The cognitive study of brains is essentially a field sprouted from a metaphor.

Metaphors in Modern Science

Even in modern times, we continue to use old metaphors and introduce new ones. As we still lack an understanding of the brain, metaphors are employed to try to understand how it operates and what it is. An example is Van Gelder’s example of Watt’s centrifugal governor, a conceptual metaphor to try to explain how simple dynamic systems can produce complex behavior without operating on computational principles.

One could also argue that modern computational models operate on metaphors, like attractors in dynamic systems and prediction or surprise in the Bayesian brain, which in itself is a metaphor of the brain as a Bayesian inference engine.

While metaphors are still employed to reduce the complexity of the brain, even computational models are meant to try and describe the brain. Newer metaphors are more complex in that they are computational models meant to directly explain the brain, even if simplified. Older metaphors were a technology employed in the hope that they would give some insights.

Bridging the Physical and Mental With Metaphors

With the idea of the brain as a machine and biological evidence, the material view of the mind began to steadily take root. With this view, things like the localization of functions in the brain also flourished. This led to lesion studies and phrenology. This sort of idea made more sense in the light of the machine metaphor, where certain modular components serve certain functions.

When all you have is behavior and anatomical evidence, both entirely disjointed, a metaphor might be as well as you can do to try and bridge it. It also allows a bridgehead to be set to try and explain the brain, starting from nothing, the brain is impossibly complex. Comparing it to metaphors shows the similarities and dissimilarities.

This can still be seen today, as we still largely consider the brain akin to a digital computer on the system-wide level, even though we know the biological reality is different. Using biological evidence from the ground up to the system level of the entire brain or even subsections of the brain is still far from our understanding. So, our understanding of it as a whole still relies on metaphors.

The Power and Peril of Metaphors

Metaphors are not mere literary devices; they have profoundly influenced how we interpret and investigate the brain. They provide intuitive frameworks for understanding complex phenomena, guiding research directions, and even sparking new fields of inquiry. However, this influence goes both ways and may mislead as much as aid us.

Moreover, metaphors can become so deeply entrenched that they are no longer recognized as such, influencing scientific discourse and shaping our interpretations. For instance, digital concepts like “information processing” or “neural codes” in the brain, while initially helpful, have been criticized for their limitations in capturing the nuances of neural activity. Similarly, our metaphor towards digital computers may have led us to neglect the analog nature of the brain.

An apt metaphor may help give some intuition or understanding of how our behaviors could be instantiated, yet it typically lacks any insights into the actual mechanisms. If the explanation fits decently well, it may become sticky in the discourse and remain until something definite replaces it, regardless of how real it is. Over time, biological insights have typically disproved the metaphors. Yet, metaphors die slowly as they give us a broader understanding than the neurological minutia until it is understood in a broader context.

For example, Von Neuman concluded that the brain is not a computer when working on the digital computer, but the metaphor continues to be incredibly prevalent.

Metaphors typically tap into one similarity, like switches acting like neurons. The similarity is essentially only in the binary aspect. This may help get an initial grasp on how neurons work abstractly. The problem becomes that this notion takes root and may be assumed to be true.

The Future of Metaphors in Brain Science

As technology advances and our understanding of the brain deepens, new metaphors will inevitably emerge. The rise of artificial intelligence and machine learning has already sparked new analogies, though in a much more two-way sense.

Metaphors may be necessary to make sense of overwhelmingly complex systems while our understanding is slowly built up, brick by brick.

The age of metaphors may soon be behind us, or so one would think, but most likely, they will continue until we have an acceptable holistic explanation of the brain. Considering its complexity, it would most likely only come in the shape of mathematics or computation—which, in a way, is a descriptive model that offloads the complexity of the brain in a way similar to a metaphor. These sturdier metaphors are being empirically tested and are metaphors you can simulate. Until they become more popular, it seems likely that computer metaphors will continue, and AI ones will increase in their pervasiveness.

References:

Cobb, M. (2020). The idea of the brain: A history. Profile Books.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1985). Metaphors we live by (5. [Dr.]). Univ. of Chicago Press.

Mudrik, L., & Maoz, U. (2015). “Me & My Brain”: Exposing Neuroscience’s Closet Dualism. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 27(2), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00723