The German legacy in Namibia, like many colonial ventures in Africa, is one of brutality and mass murder on a genocidal scale. Nevertheless, Germans also left behind a series of beautiful colonial buildings. While it has to be said that the infrastructure they left behind was not built out of any sense of altruism to Namibians, the architectural remains of Germany’s colonial ambition are nonetheless interesting as they provide a window to a difficult era of Namibia’s past.

An often controversial subject, the German architectural legacy is a widespread feature of Namibia’s urban landscape.

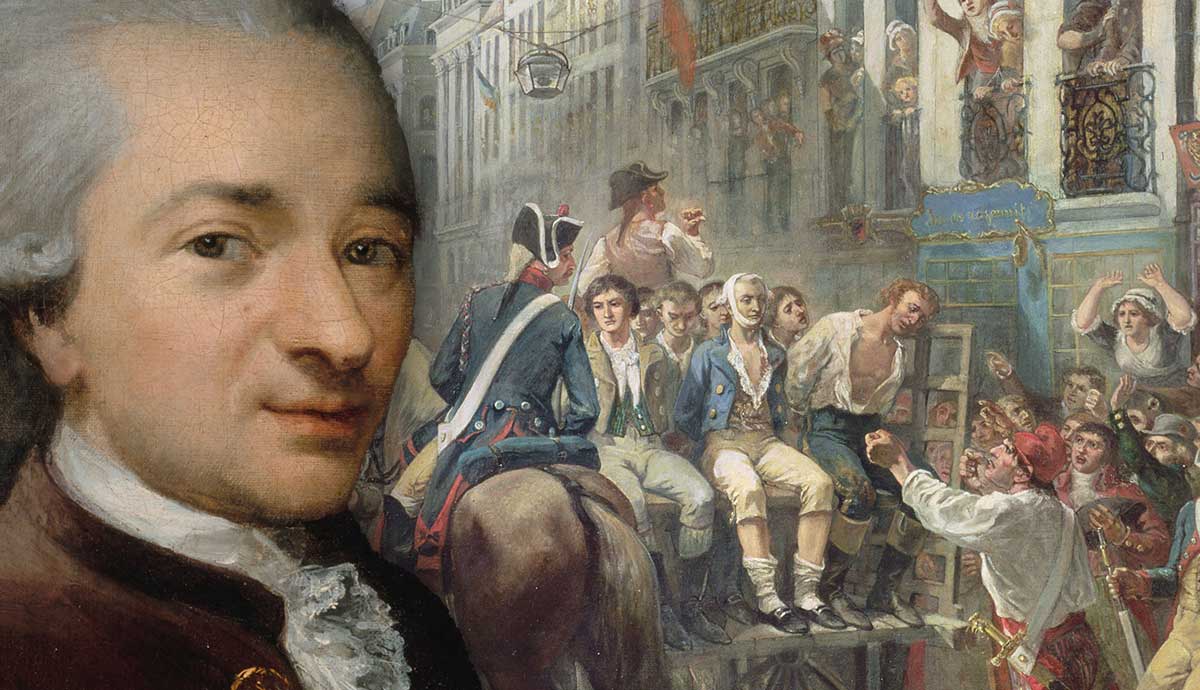

A (Very) Brief History of German South West Africa

In 1840, the London Missionary Society handed over its activities to the German Rhenish Missionary Society in what would become German South West Africa. Churches were established while farmers and merchants began setting up operations. Thus started the German colonial legacy that would be built over the next seven decades.

In the early 1880s, Germany staked its imperial claim on the territory, and from 1884 to 1885, these claims were agreed upon by other European powers at the Berlin Conference, which was held to partition the continent between the colonial powers of Europe.

Soon after, the Germans sent troops to consolidate their political gains, and fighting broke out between the colonizers and the local people, most significantly the Nama (or Namaqua). Ongoing conflict would characterize the colonial endeavor for many years to come.

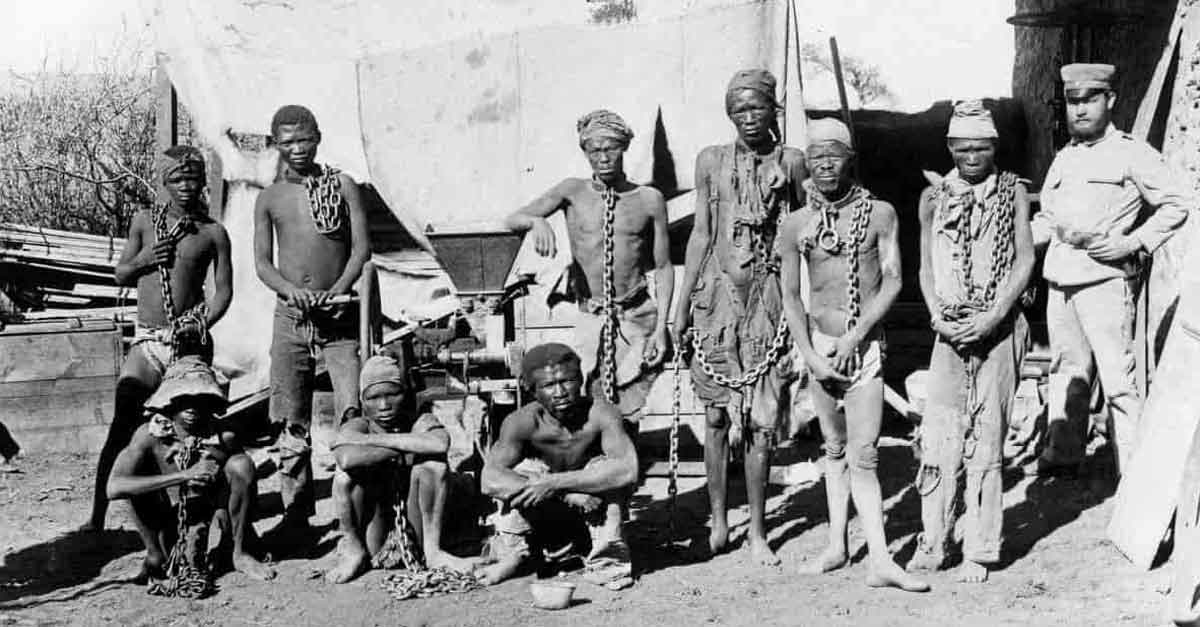

At the beginning of the 20th century, German immigration to German South West Africa increased, especially after the discovery of diamonds in 1908. The period around this time was marked by rebellions of the native people, and vengeance meted out by the colonial forces. So severe were the reprisals that today it is considered a genocide. According to the Wiener Holocaust Library, between 1904 and 1907, it is estimated that between 50,000 and 65,000 Herero people were killed, while another 10,000 Nama people were added to this harrowing statistic.

The Germans built concentration camps and subjected the Herero and Nama people to such severe conditions that the majority of those imprisoned died of disease, abuse, starvation, and exhaustion. Experiments were carried out in a similar fashion and mindset used by the Nazis four decades later.

It was only in 2021 that a formal apology was issued by the German government and €1.1 billion was agreed to be paid in reparations over the course of the next 30 years.

In 1915, during the First World War, South West Africa was invaded by forces of the Union of South Africa, who put an end to German rule in the territory. This, however, was not an end to oppression but the beginning of a new one, as South West Africa remained under South African control until 1990, when it became the independent country of Namibia. For much of this time, the country was subjected to the harsh apartheid laws that governed South Africa.

Form and Function

German colonial architecture at the time of German presence in South West Africa is indicative of a Wilheminian style that existed from 1870 to 1914. It can be considered neo-Baroque, with large rooms and windows and stucco ceilings. With its distinctive style, this form of architecture stamped German presence on the territory in an overt way. Of course, architecture from the colonial period is not singular and displays a variety of influences. Even elements of Art Nouveau can be found in Namibia’s colonial structures.

The buildings themselves were obviously not just decorative. They filled important functions from housing to bureaucracy and everything in between. There are military buildings, hotels, lighthouses, prisons, business buildings, libraries, and many other interesting buildings that reflect the desires of German colonial ambition at the time. Some of these buildings are still used for their intended purpose, while others have been repurposed.

Prime Examples

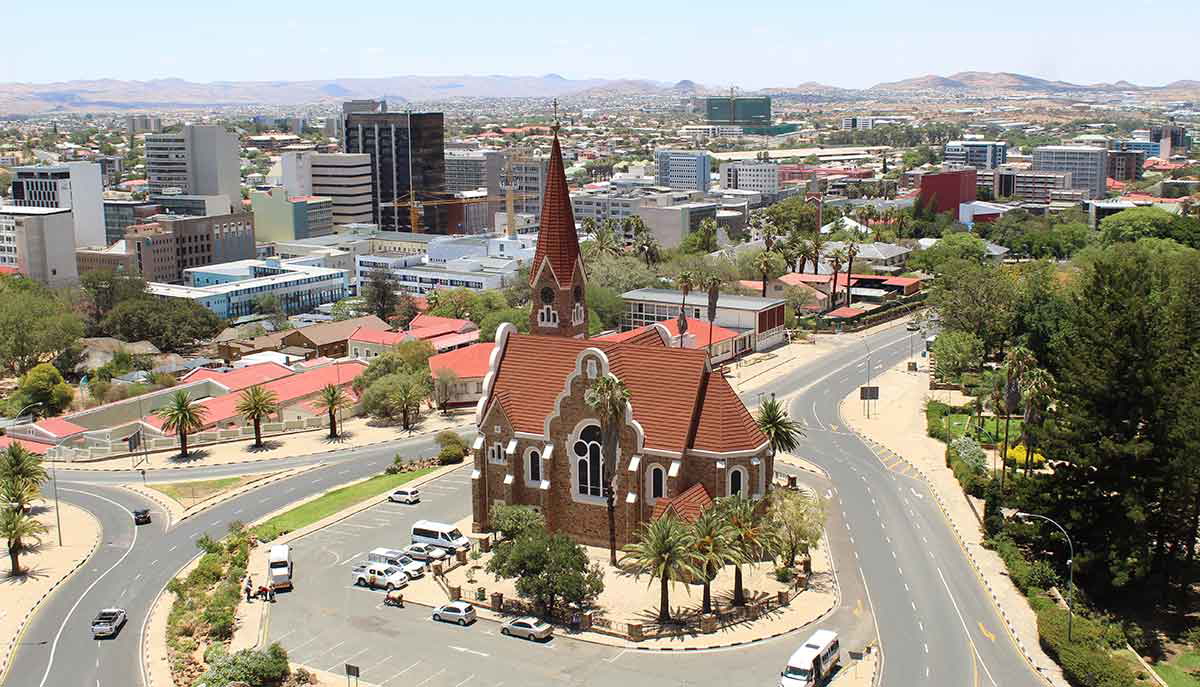

German culture and its architecture can be seen throughout Namibia, both on the coast and much further inland. Of major importance was the capital city of Windhuk (now Windhoek), which served as a seat of power for German administration over the territory. With a current population of just under half a million people, Windhoek remains the capital and biggest city in Namibia.

The city is filled with famous landmarks. One such building is a small castle called Schwerinsburg. It started out as just a tower in 1891 and was sold by the army to an architect in 1904, who converted the construction into a beer garden. In 1913, the tower changed hands again. It was bought by Dr. Hans Bogislav Graf von Schwerin, who employed the former owner to convert the tower into a castle. Today, the castle serves as the home of the Italian Ambassador to Namibia. In the nearby vicinity are two other castles, Sanderburg Castle and Heinitzburg Castle, the latter of which now serves as a hotel and restaurant.

One of the most famous German colonial buildings in Namibia is a fort called the Alte Feste, which began construction in 1890 and was intended as a headquarters for the colonial military force (Schutztruppe). After South West Africa was taken over by South Africa in 1915, the fort served as a headquarters for the South African Union Army in the region. In 1990, South Africa relinquished control over South West Africa. The Alte Feste became a home for the historical collection of the National Museum of Namibia. The building, however, was closed to the public in 2023 and has been in desperate need of renovation.

The Tintenpalast, which serves as Namibia’s parliament building is also of special note with its Neoclassical façade. It was built between 1912 and 1913 with the use of Nama and Herero slave labor. It served as an administrative building for the German colonial government.

The city of Swakopmund is well-known for its German heritage in its architecture, and evidence of German colonial history can be seen throughout the city. The Altes Gefängnis (Old Prison) was built in 1909 and still serves as a prison today. Woermannhaus, built in 1905, housed trading company offices before becoming a school hospital and then a hostel for sailors. Today, it serves as a library and is a striking landmark in the city, as it stands on high ground and has a tower from which visitors can get impressive views of the urban area and the sea.

Arguably, the most impressive building in Swakopmund is the Hohenzollernhaus, with its neo-Baroque façade. Built in 1909, it served as a hotel during colonial times but now houses private apartments. Similar to the Alte Feste in Windhoek, Swakopmund is also home to a fort called Die Kaserne, which was built in 1905 and served as a barracks for soldiers who fought in the Herero Uprising and helped build the town’s infrastructure.

On the southern coast of Namibia in the ǃNamiǂNûs constituency is the town of Lüderitz, founded in 1883. With labor provided by Herero and Nama slaves, many of the town’s iconic structures were built over the following years. Among such buildings are the Deutsche Afrika Bank, which was proclaimed a national monument in 1980, and the Felsenkirche, a German Evangelical Church built between 1911 and 1912 that overlooks the town. The church, built in the vertical Gothic style, has been an official national monument since 1978.

Famous not for its original intention but for its unique appearance today is the ghost town of Kolmanskuppe (or Kolmanskop). Founded in 1908 when diamonds were discovered nearby, the town was typified by German architecture and had many amenities. As the diamond mine became depleted, the population of the town diminished, too, until Kolmanskuppe was completely abandoned in 1956 and left to the sands and desert winds.

What remains is a bleak and empty vestige of German colonial enterprise—a fitting representation of Germany’s colonial fate. Now, the town hosts tourists and has become a unique location in the film and television industry. Kolmanskop served as one of the locations for the 2024 television series Fallout.

Mixed Feelings

The topic of German architecture and buildings in Namibia today is one that generates much debate. The German occupation was one in which genocide happened. As a result, there is a level of national trauma associated with the visual representation of German control. This trauma extended past German control and into many decades of control and oppression by apartheid South Africa.

Despite being painful reminders of the past, German colonial buildings are considered part of Namibia’s cultural heritage. Determining the validity of individual sentiment becomes problematic when attempting to forge a unified identity with such a troubled past. While some may not be affected by negative feelings at viewing such structures, others perceive the need for visible change. The debate thus moves to what should be preserved and what should be removed.

One such example, in Windhoek, is the Reiterdenkmal, a statue of a German colonial officer which was removed in 2009 to make way for the building of the Independence Memorial Museum. The statue had been a subject of fierce debate over the years since independence. After it was placed in 2010 in front of the Alte Feste, a German fortress and museum, protests continued. The statue was finally moved into storage at the Alte Feste. Where the statue once stood is now a statue of Sam Nujoma, Namibia’s first president—a clear sign of the nation reclaiming its identity.