Oliver Cromwell is a contentious figure in the history of the British Isles. In England, he is usually regarded as an effective military leader who led the Parliamentarians to victory against King Charles I’s autocratic government. However, Cromwell’s actions in Ireland during the 1640s and 1650s were particularly notorious. The brutality of the Cromwellian Conquest still affects Ireland today, where he continues to be seen as one of history’s greatest villains.

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

The 1640s and early 1650s in Britain and Ireland were a very bloody time. A series of conflicts, including the Bishops’ Wars, First and Second English Civil Wars, Irish Confederate Wars, Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland and the Anglo-Scottish War devastated the British Isles between the years 1639 and 1653. The conflicts were caused by religious, political, and ethnic differences, with numerous shifting of alliances even within the different factions. At various points nearly every faction had allied with each other in some theater of the conflict, known collectively as the Wars of the Three Kingdoms.

King Charles I of England, Ireland, and Scotland clashed with the English Parliament over his political authority. He also was dealing with religious conflict with Scottish Covenanters and with reformed Protestants in England. Lastly, he faced a widespread uprising in Ireland where Catholic rebels wanted an end to discrimination and desired greater autonomy. The confused fighting left hundreds of thousands dead from not only the war but also disease and famine.

The Parliamentarian forces defeated first the Royalist faction, then the Scottish Covenanters. The last, and some would say, the most vicious, fighting took place in Ireland, where Cromwell is still vilified today. Britain and Ireland would be irrevocably changed by the 1650s. As Lord Protector of England, he ruled over a republican government in England, Scotland, and Ireland known as the Commonwealth, though it was effectively a military dictatorship. The Cromwellian Commonwealth collapsed into anarchy after Cromwell’s death in 1658 and the Stuart monarchy was restored with Charles II in 1660. The restoration was short-lived, as Charles’ brother and successor James II would in turn be overthrown by William of Orange in 1688.

Ireland: Neither Royalist or Parliamentarian

The Catholic Confederation grew out of the 1641 rebellion, an attempt to overthrow Protestant rule in Ireland but which soon embroiled the island in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Felim O’Neill, a relative of the famous Hugh O’Neill, claimed Charles I had authorised him to secure Ireland against his English and Scottish enemies. The uprising went out of control in several areas, particularly Ulster, and numerous massacres were committed on the Protestant settler population. These prompted an English (both Royalist and Parliamentarian) response along with the landing of a Scottish Covenanter army in Ulster.

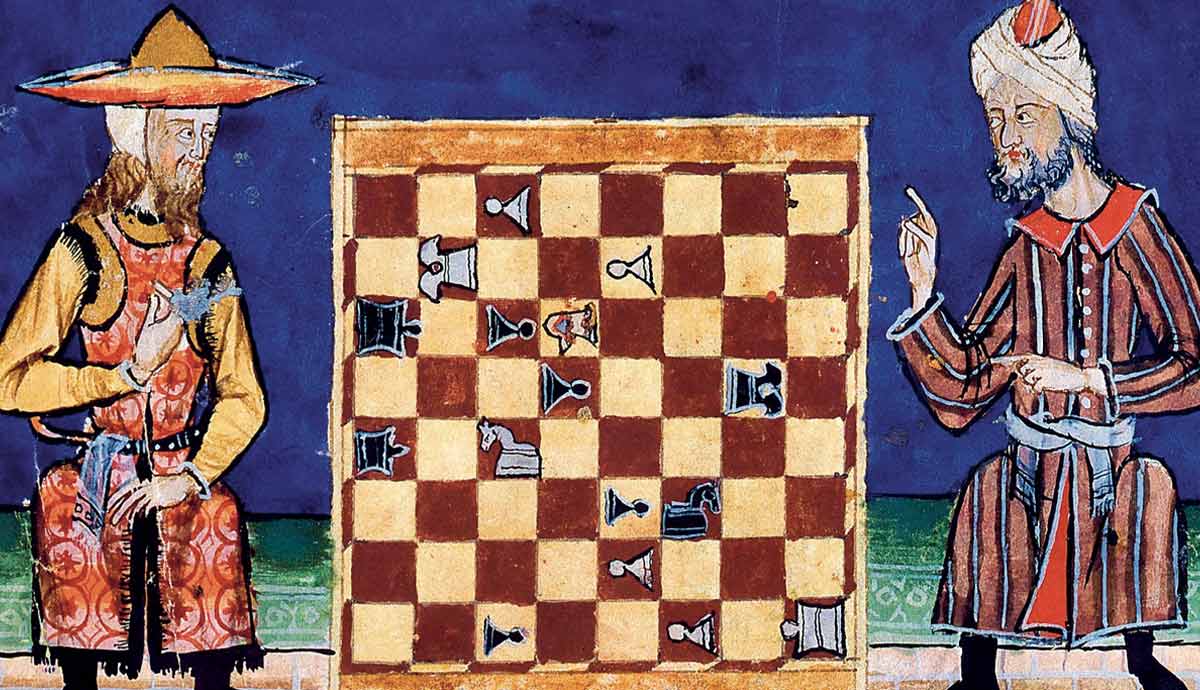

The Confederation was founded in 1642 and was a bizarre mix from the start. It included Catholics of both Gaelic and Old English descent. It had members who wanted revenge for the Plantations and Nine Years War alongside Royalists. The Confederation was recognized abroad and controlled the lion’s share of Ireland but it was hampered by infighting. It fought against the Scottish Covenanters, English Royalists, and Parliamentarians, though the two former groups would eventually ally with the Irish Confederates after the Parliamentarian threat became apparent.

The Confederates achieved some successes, with Benburb in 1646 being a brilliant victory in the field against Scottish troops. Meanwhile, an expeditionary force sent to Scotland to support Montrose ran rampant around the Highlands for more than a year, defeating six different Covenanter armies. Ultimately, the Confederation was its own worst enemy. Its peace with the Royalists and Covenanters came too late to defeat Cromwell’s New Model Army.

The New Model Army

Often seen as the first professional standing army in Britain, the New Model Army was the main reason for the Parliamentarian victory in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, and its ultimate undoing. It was a professional force that could serve anywhere, unlike the local militias or Trained Bands who were reluctant to serve outside their own localities. Officers were forbidden from holding political office and soldiers came from diverse backgrounds.

The army had designated infantry, cavalry, and artillery units. The infantry were armed with pikes and muskets with a ratio of two musketeers per pikeman. Cavalry were the elite of the army, showing remarkable discipline, unlike their enemies who were prone to breaking formation to loot the enemy after a victory. They even earned the nickname “Ironsides” from their enemy, Prince Rupert of the Rhine, whose cavalry had decimated the Parliamentarians in the early stages of the war. The artillery were probably the weakest branch as Cromwell and other commanders were inexperienced in siege warfare and preferred to take towns by storm, a costly endeavour.

Although popularly portrayed as a deeply religious force, the New Model Army was no collection of saints. Puritans in their ranks complained of their fellow soldiers drinking, gambling, and swearing. Mutinies did occur, though generally during lulls of peace. Discipline was tough, Cromwell hanged two of his own soldiers in Ireland for stealing chickens from an old woman. Parliamentarian soldiers were as guilty of atrocities as their Royalist counterparts but the leadership came down hard on unauthorized actions. The New Model Army enforced Cromwellian rule in the new Commonwealth of England.

Rathmines and Drogheda

The first major battle with Cromwellian forces was fought near Dublin. By 1649, nearly all of Ireland was in Confederate hands and Dublin was the last remaining stronghold, willingly handed over to Parliament by the Royalists holding it. A Confederate army was routed at Rathmines by the English garrison, granting Cromwell a safe port to land his troops. He landed two weeks later on August 15, immediately marching to attack the other eastern settlements.

Drogheda is one of the most infamous events of the Cromwellian Conquest. A week-long siege saw the town taken and most of the garrison put to the sword. This savage policy of no quarter was the norm on the continent for a settlement that resisted its besiegers, but it had rarely happened in Britain and Ireland. The Cromwellian forces viewed it as appropriate for Ireland if not England.

Cromwell’s forces sacked Wexford and besieged Waterford. The brutal atrocities had a mixed effect as a terror tactic. Some cities surrendered immediately with terms while others resisted with greater intensity. With the ports secured, Cromwell could rely on steady shipment of supplies and reinforcements from Britain. Charles also came to a separate peace with the Commonwealth, leaving only the most diehard Royalists fighting alongside the Confederates. The scales were rapidly tilting in Cromwell’s favor though there was much fighting yet to be done in Ireland. The Irish cause was not helped by internal divisions and lack of a coordinated strategy.

The Cromwellian Conquest

Cromwell continued his systematic conquest in spring 1650, first securing the final towns in Leinster before pushing into Munster. He took heavy losses besieging Kilkenny and Clonmel but honored terms of surrender with civilian populations and military garrisons. Clonmel is notable as it was a serious, albeit, temporary repulse. The defending garrison included veteran soldiers from the Confederates’ Ulster army. Their defense inflicted heavy casualties and Cromwell faced a near mutiny when his infantry refused to continue storming the breach.

Even after the defeat of the last armies in Ireland, there still remained thousands of armed men in the country, prosecuting public and private wars against the Commonwealth forces. Commonwealth soldiers could only travel safely and in large bodies, and areas were designated free fire zones where anyone found could be killed without penalty. Food stocks were destroyed in several counties, prompting widespread famine. There was also an outbreak of bubonic plague which ran rampant in the countryside, indiscriminately killing both sides. Supply convoys were said to be at risk of attack the moment they were more than two miles from a friendly garrison. The depredations of the partisans prompted several punitive expeditions in an effort to pacify the island.

Cromwell and his senior officers adopted increasingly draconian measures to restore law and order, just as how they had ruthlessly dealt with the Clubmen (hastily formed civilian militias) in England. Local commanders were given cartes blanches to deal with insurrection as they saw fit.

“To Hell or to Connacht”

Ireland was an island on its knees by the 1650s. War, disease, and famine inflicted a heavy toll on soldiers and civilians alike. The last army did not lay down their arms until 1653, motivated by the Commonwealth terms that allowed them to leave Ireland and serve in foreign armies in Europe, similar to the terms granted to Jacobites in the Williamite War. Parliament declared the war over in September 1653 but low level warfare would persist for several years. These tories (from the Irish Tóraí meaning bandit or outlaw) continued to raid and ambush though some were simple brigands motivated by personal gain rather than politics.

The terms of the settlement were harsh. Catholic land ownership fell from 60% to 20% by 1660. Irish landowners were forcibly transported from richer lands in the east of the country to west of the Shannon, the origin of the phrase “to hell or to Connacht.” New plantations were set up as land was granted to veterans of the New Model Army. Thousands of Irish were shipped to the Caribbean and North America as indentured servants.

As shocking as the sacking of Drogheda or Wexford were, the real bitterness comes from the counter-guerrilla tactics carried out by the Cromwellian forces in what is considered to be the most ruthless campaign of the Wars of the Three Kingdoms, though numerous atrocities had already been carried out by Irish, English, and Scottish forces in the 1640s. However, the fighting in Ireland exhibited savagery that was mostly the exception rather than the norm in England and Scotland.