The myth of the Phoenix is closely identified with stories from ancient Greek and Roman literature, although there are Egyptian and Persian counterparts that may have outdated and influenced these. What is less well known are the references to the phoenix and phoenixlike birds from the poetic and prophetic sections of the Hebrew Old Testament and the Jewish Apocrypha. Christian popes and poets have interpreted these as symbols for key New Testament doctrines, such as spiritual regeneration and bodily resurrection, but especially the resurrection of Jesus from the dead.

The Ancient Middle East and the Phoenix

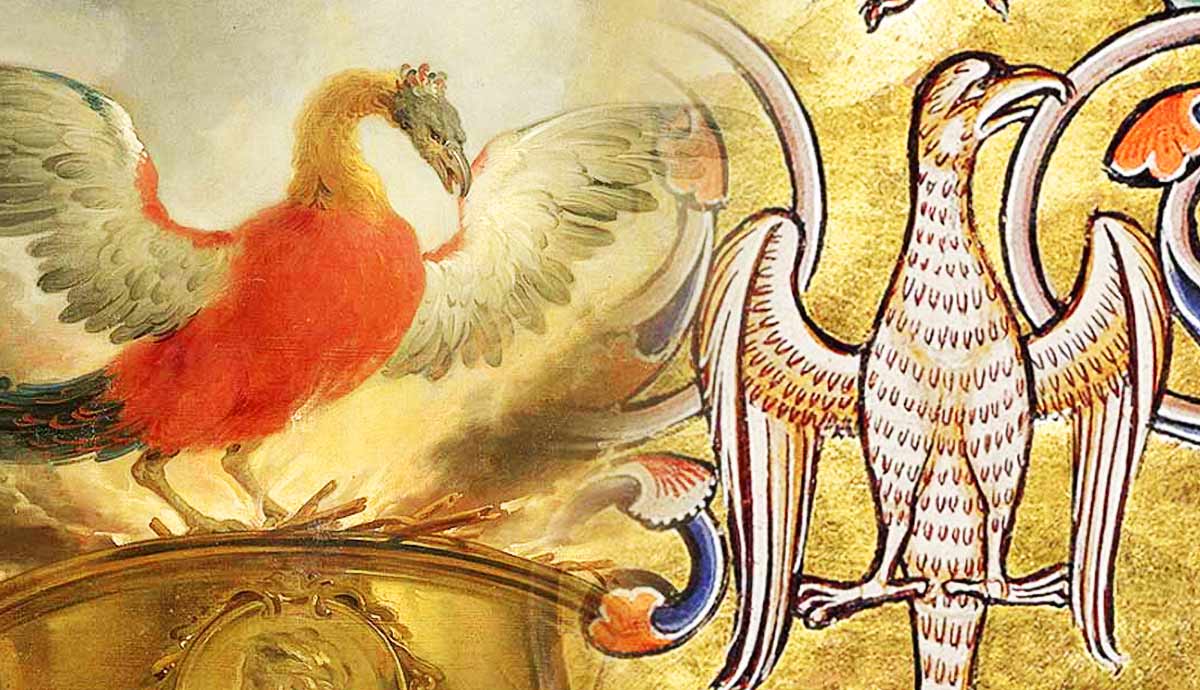

The Phoenix is a legendary bird from the folklore of ancient Greece associated with fire and rejuvenation. The first reference to a phoenix in Greek literature is in an 8th-century BCE poem by Hesiod called the Precepts of Chiron. Chiron, the wise centaur that mentored Achilles, tells of the phoenix that far outlives human lifespans. Possibly the most significant telling of the phoenix tale is by Herodotus in his Histories (5th century BCE), who calls it a sacred bird of the Egyptians.

There is debate among scholars about the direction of influence between Greek and Egyptian conceptions of the phoenix. The Egyptians had their own version of a solar bird related to rebirth called the Bennu. There is also a Persian version of the phoenix called the Simurgh—a benevolent, eagle-shaped bird that lived a long life before immersing itself in flames. Since these myths predate the Greek version and were contemporaneous with the ancient Hebrews, they may have had an influence on biblical literature, and ultimately on Christian symbolism.

Much later on (1st century CE), in his Natural History, the Roman naturalist Pliny the Elder described the phoenix as an eagle-sized bird, purple in color, with a golden neck and a crested head. Pliny does admit that an alleged phoenix sent to Emperor Claudius in 47 CE was likely a fake. The Latin author Claudian (4th century CE), in his poem The Phoenix, wrote that the bird has a mysterious fire that “flashes from its eye” and that its crest “shines with the sun’s own light.” It seems neither of them takes the phoenix story as literal fact.

Is the Phoenix in the Book of Job?

It is fitting that the major biblical reference to the phoenix may be found in the Book of Job. Job is generally considered to be the oldest book of the Old Testament and contains material with a primeval feel, such as encounters with ghosts and celestial beings (chapters 4 and 33). More relevant here, it contains the most detailed references in the Bible to other mythic creatures, especially Behemoth (Chapter 40) and Leviathan the sea monster (chapter 41).

There is a verse in Job that has proved controversial to translators and scholars. It is found in Job 29:18:

“So I thought: ‘I will die in my nest, and multiply my days as the sand.’”

The Hebrew word for sand is “chol.” A minority of Bible versions interpret this final word in the verse as “phoenix” rather than sand. They make this claim from the parallels they find between Job and Ugaritic texts. They also argue that this interpretation makes more sense in light of the reference to a nest in the first part of the verse. The JPS Tanakh (a Jewish translation of the Hebrew Bible), the New American Bible, and the New Revised Standard Version all translate it as “phoenix.”

Phoenixlike Birds in the Psalms and Prophets

While there are no other texts in the Bible that could be argued to name the phoenix, there are verses that seem to refer to a phoenixlike bird, one that possesses the power of regeneration and eternal youth. This bird is usually designated as an eagle. However, we should be careful not to impose our modern, scientific taxonomy of species on these ancient texts.

Psalm 103:5 blesses God for all the benefits he has bestowed on the poet, including satisfying his soul with good things so that his “youth is renewed like the eagle’s.” Some commentators take this as an allusion to the ancient belief that eagles renew their youth with their new plumage. Others take it to mean the soul of the psalmist is refreshed in strength and given the vigour of an eagle, often pointed to in the Bible as one of the most powerful of creatures with its ability to soar in the skies.

This imagery, language, and association of ideas is repeated in Isaiah 40:31:

“Those who hope in the LORD will renew their strength. They will soar on wings like eagles; they will run and not grow weary, they will walk and not be faint.”

Here, again, the eagle is a metaphor for strength, and not just any strength, but a renewed life-force. The Hebrew word for renew here means to change for the better, to pass from one state to another. It also means to show newness, like when a tree puts forth fresh shoots.

Finally, some find an indirect reference to phoenixlike images in Malachi 4:2, which pictures “the Sun of Righteousness rising with healing in its wings.” In some versions of the phoenix myth, it is from the sun that the bird gains its power to rise above the gravity of time and heal its own body from old age.

Is the Phoenix a Class of Angel?

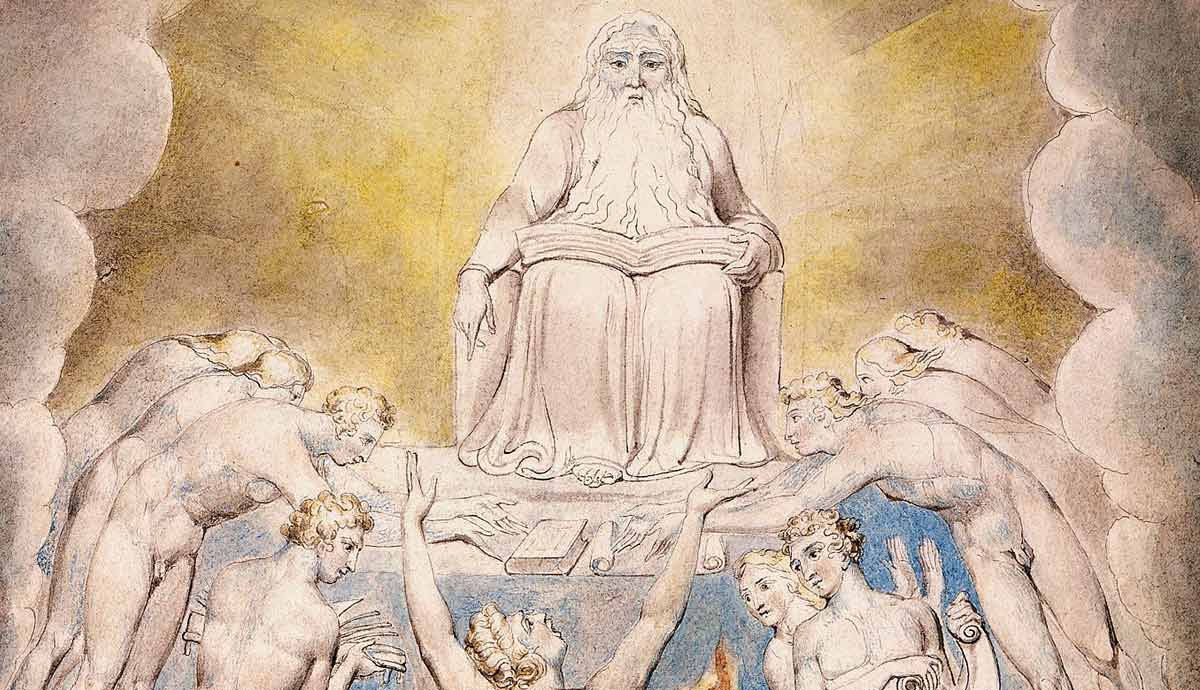

The Second Book of Enoch is a book of the Jewish apocrypha written in the 1st century CE. Chapters one to 22 describe the journey of the patriarch Enoch as he is translated at the age of 365 from Earth to the highest heaven, where God is enthroned. This journey takes him through multiple heavens, ten in total, with a variety of cosmic and celestial phenomena associated with each level.

The fourth heaven contains the Sun and the Moon. Myriads of angels follow the circuit of the Sun, while others with six wings keep it lit. Then, in Chapter 12, the author writes this.

“And I looked and saw other flying elements of the sun, whose names are Phoenixes and Chalkydri, marvellous and wonderful, with feet and tails in the form of a lion, and a crocodile’s head, their appearance is empurpled, like the rainbow; their size is nine hundred measures, their wings are like those of angels, each has twelve, and they attend and accompany the sun, bearing heat and dew, as it is ordered them from God.”

Both before and after the mention of these heavenly creatures, angels are mentioned, and not just angels, but angels of different varieties and functions. This has led some scholars to classify the Phoenixes and Chalkydri as two further possible angelic orders, close to each other in kind, since they are described together.

While some point out their difference from the phoenix of Greek myth, there are also similarities, such as their winged form and their close association with the sun, and especially, with the sunrise and morning time. According to Enoch, the Phoenix breaks out into singing at the start of every new day, making birds stir and flutter their wings on Earth. And so, it is associated with both newness of life and feathered creatures.

Clement of Rome on the Phoenix

In his Letter to the Corinthians, the early Christian leader Clement of Rome explicitly referred to the legend of the phoenix, which he called an “emblem” and “sign” of the Resurrection. The context is Clement’s attempt to show that nature shows analogies of the Resurrection, such as sunrise from night and springtime from winter. Then, in Chapter 25, he tells the story of the phoenix, a bird from eastern lands. This story is essentially a retelling of Herodotus.

The phoenix, Clement wrote in the first century CE, is unique and lives up to 500 years. When death beckons, it makes a nest of spices and dies. As its body decays, a worm is produced that is nourished by the juices of its dead parent. It eventually grows in strength and sprouts feathers. When it is fully grown, it flies off and carries the bones of its predecessor to the city of Heliopolis, where it places them on the altar of the sun before returning home.

“Do we then deem it any great and wonderful thing for the Maker of all things to raise up again those that have piously served Him in the assurance of a good faith, when even by a bird He shows us the mightiness of His power to fulfil His promise?”

The Phoenix in Old English Poetry

There are many literary references to the phoenix in the works of well-known English authors such as Shakespeare and D.H. Lawrence. However, it is in a more obscure and ancient work that the phoenix receives perhaps its greatest Christian treatment in this language. This is in an anonymous poem in Old English called The Phoenix. Since it is found in the Exeter Book—a large, hand-written manuscript of Old English poetry—it was probably written around the 9th or 10th century CE.

The poem consists of two parts. The first half is a description of the perfect Garden of Eden, and a beautiful Phoenix that watches over it, ruling other birds, growing old and dying, then undergoing a rebirth from the ashes of its old self. The second half is an allegorical exploration of Chris’s death and resurrection. Here, the Phoenix not only symbolizes Christ, but also death and rebirth of Christians in this life (spiritual regeneration), and the next (bodily resurrection).

“Now just so after death, through the Lord’s might, souls together with body will journey—handsomely adorned, just like the bird, with noble perfumes—into abundant joys where the sun, steadfastly true, glistens radiant above the multitudes in heavenly city.”

This poem has various sources. While the first half uses Genesis for context, it is largely an adaptation of the Latin poem De Ave Phoenice by early Chrisitan author Lactantius (3rd to 4th century CE). The second half is more explicitly based on the Bible, especially Job 29:18 and heavenly imagery in the Book of Revelation.

C.S. Lewis on the Phoenix

C.S. Lewis is a modern author who has used the phoenix in a wide variety of literary forms. In his children’s fantasy series The Chronicles of Narnia, a wonderful bird—larger than an eagle with a golden-colored breast, scarlet crest, and purple tail—roosted in an Edenic garden (The Magician’s Nephew). Later on, in The Last Battle, it is identified as a phoenix, or rather “the Phoenix.”

Lewis also wrote three poems that make reference to the phoenix and make use of its symbolic significance. Victory is a humanist poem that laments the death of legend while celebrating the “yearning, high, rebellious spirit of man.”

“Though often bruised, oft broken by the rod,

Yet, like the phoenix, from each fiery bed

Higher the stricken spirit lifts its head

And higher-till the beast become a god.”

The Turn of the Tide is a Christmas poem by Lewis that makes the Incarnation of Christ—rather than the Resurrection—the turning point for change in all of human history. “In his green Asian dell the Phoenix from his shell / Burst forth and was the Phoenix once more.” But it is in his lesser-known poem The Phoenix that Lewis most clearly uses the mythic bird as a symbol of Christ, similar to Aslan in Narnia. Here he seems to beg his readers to look upon that fabulous wonder, and not to break his heart by fixing our eyes “on me, not on the Bird.”

“The Phoenix flew into my garden and stood perched upon

A sycamore; the feathered flame with dazzling eyes

Lit up the whole lawn like a bonfire on midsummer’s eve.”