Before the 16th century, Portugal played a major role in maritime trade as a hub of exchange between the Mediterranean, Atlantic, and Northern European markets. By the late 16th century, Portugal not only grafted itself onto the pre-existing Indian Ocean trade, but also created new trade flows and established new structures of power to protect their commercial interests.

Al-Lixbûnâ

Before becoming one of the dominant Christian empires in the Indian and Atlantic oceans, Portugal had lived under Muslim rule for several centuries. Along with present-day Spain and Southern France, Portugal comprised part of the Muslim-ruled ‘al-Andalus,’ or ‘country of the Vandals,’ beginning in the 8th century (Disney, p. 53).

Al-Lixbûnâ, the Arabicized name of Lisbon, was part of the “first global age” during the 11th century (Lains, p. 201). The port city prospered as part of a network of exchange that circulated silk, copper, jewels, citrus, textiles, and other items arriving from maritime trade routes connecting East Asia to the Arabian Peninsula. These objects filtered into the Mediterranean via Muslim traders in present-day Turkey and the Levant or in North Africa.

Lisbon acted as the midway point between merchants coming and going from the Mediterranean and Northern Europe, seeing as it was positioned facing the open seas of the Atlantic. A Flemish shipping list from the 12th century lists over 34 countries with shipments coming to Bruges, as well as their products—liquor and almonds from Navarre, saffron and rice from Aragon, and dried fruit, honey, and leather from Portugal (Lains, p. 201). It is likely many of these objects arrived on merchant ships coming from Lisbon.

Age of Crisis to Age of Exploration

Muslim rule came to an end in Portugal beginning in the 12th century. The 1147 Siege of Lisbon, the only Christian victory of the Second Crusade, saw the city return to Christian rule. The event consolidated the rule of Afonso Henriques, who proclaimed himself the first king of Portugal several years earlier. Armed with its own language (however with many words borrowed from Arabic), a Kingdom, and under the umbrella of Christianity, Portugal became a nation. Over the following centuries, Christian kingdoms in the Iberian Peninsula gradually conquered al-Andalus from its Muslim rulers as part of the Reconquista.

However, Portugal’s fortunes wavered during its initial period of independence. The kingdom was heavily impacted by the spread of the Black Death, which likely entered the country through Lisbon in 1348. Like many European cities, it lost almost one-third of its population. Following the plague, Portugal was hit by several other disasters ranging from civil wars, famines, and earthquakes. The 14th and early 15th centuries in Portugal are referred to as an “age of crisis” (Disney, p. 108). How then, did Portugal become one of the largest global maritime empires by the end of the 15th century?

Portugal turned towards trade as a viable source of income after the economic losses of the Black Death. The Iberian peninsula became more integrated, with trade flowing between Portugal, Castile, Aragon, Valencia, Catalonia, as well as commercial cities further afield, such as Florence. The latter had a revolutionized banking system that created a new class of people with the capital to purchase goods coming from long distances. At the same time, Portugal was slowly building a strong navy.

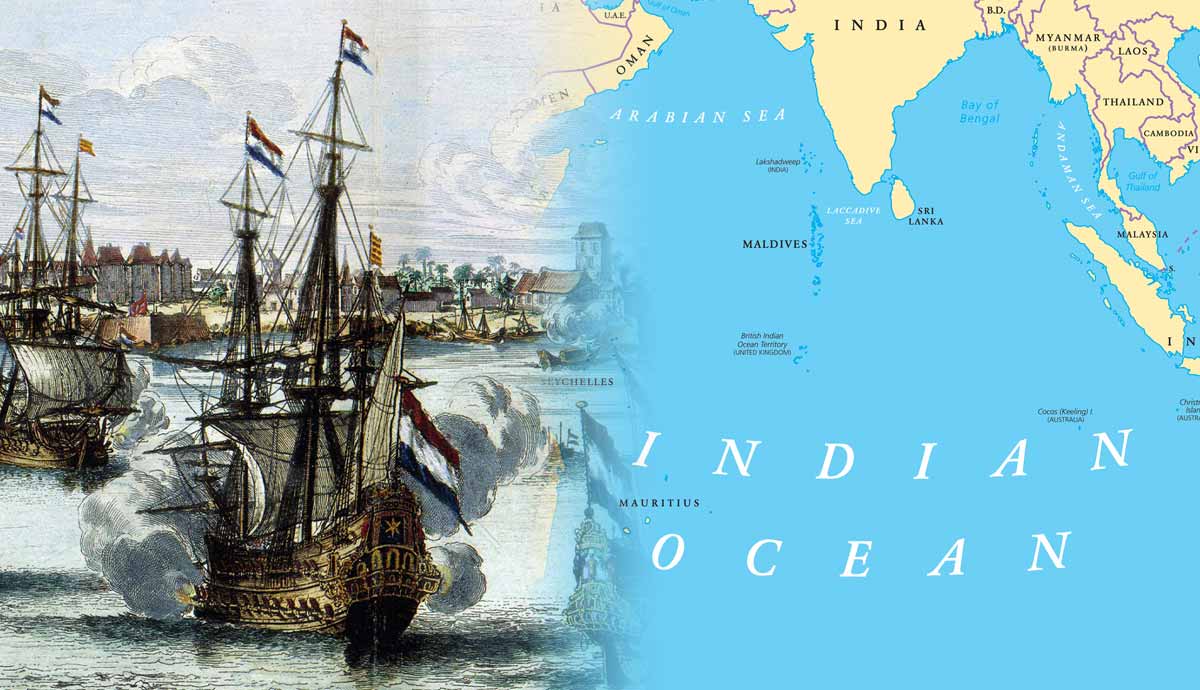

The ability to build and maintain a formidable fleet of ocean-going ships enabled Portugal to embark on the ambitious project of finding an alternative route to India, the center of the vast Indian Ocean trade network. The cannon placed on Portuguese ships would also put them at an advantage against the largely unarmed merchant ships in the Indian Ocean.

Further, due to a long-standing relationship with Arabs, via al-Andalus, and continued trade with Arab and Muslim nations in the Mediterranean, the Portuguese acquired the sailing technology employed by merchants of Arabia and Persia who routinely sailed across the Indian Ocean along trade network between East Africa and China known as the ‘maritime Silk Road.’ A desire to be directly involved in this trade, and the potential wealth they could accumulate by cutting out middlemen, was one of the guiding forces behind Portuguese maritime expansion in the 15th and 16th centuries.

Portugal and the Spice Trade

The spice trade was one of the dominant forms of trade in the Indian Ocean. This included pepper, cinnamon, ginger, cloves, nutmeg, and mace. Until the 19th century, the last three grew only in the humid environment of the Maluku Islands in present-day Indonesia, adding to their value. The spice trade was especially lucrative due to their various uses in medicine, cuisine, perfumes, and religious rituals.

Prior to the 16th century, pepper was brought into Europe primarily through the Venetians. The spice would travel from Southeast Asia to the Malabar Coast (southwest India) before being brought to Cairo by Gujarati and Arab merchants. From Cairo it would travel to Alexandria, where it would be acquired by Venetian merchants who carried it into Europe. However, after the 16th century, Portugal secured a stronghold in Malacca (Malaysia), one of the main entrepots for spices from Indonesia. This caused ripples in the supply chain for spices, especially pepper, that circulated the Indian Ocean and eventually Europe.

Portugal became one of the largest suppliers of pepper in the 16th century, with 60,000-70,000 quintals annually by the end of the 16th century (Hancock, p. 227). This is the equivalent of around 7.8 million pounds or 3.5 million kilograms. The dominant Portuguese presence in Malacca caused merchants to establish new trading posts elsewhere, changing nearly 200 years of trading history in the port city. In the case of spices, merchants circumnavigated Portuguese power by diverting to other ports, such as Sumatra and Java in Indonesia.

Portugal and Sino-Japanese Trade

Once Portuguese sailors reached Malacca, they didn’t stop there, but continued eastward towards China, where they were allowed to establish a trading post in Macau (southern China) by the Ming Dynasty (1368 to 1644 CE). However, during a voyage in 1543, winds blew merchant ships to land unexpectedly on the island of Tanegashima in Japan. This moment ushered in the beginning of trade between China and Japan, with Portugal as the mediator. The Ming Dynasty had placed a trading ban on Japan, which had been active for almost a century. Acting as intermediaries, Portugal reconnected two regions that had been previously detached.

Portugal regularly facilitated the movement of silver from Japan to China. Silver was highly desired by China because it functioned as one of its main forms of currency, especially for taxes, but was one of the few natural objects it couldn’t produce itself. Meanwhile, Japan desired silk from China, perceived as the ideal material for kimonos, book bindings, and samurai cloaks. This role as intermediary came at a time when massive silver deposits were found in Japan in Iwami Ginzan in 1526 (Hancock, p. 229). The flow of silver from Japan to Macau was accompanied by the export of gold, porcelain, and silk from China in increasing quantities to Portuguese trading posts throughout the Indian Ocean, which then made their way to European markets.

Cowries as Currency in the Transatlantic Slave Trade

Cowries from the Maldives, the archipelago southwest of present-day Sri Lanka, were used in cultures throughout the Indian Ocean as adornments, everyday objects, materials for rituals or ceremonies, and also as currency. Cowries even travelled as far as West Africa as early as the 7th century, carried along the caravan route of the Trans Sarahan trade network. The Portuguese early in the 15th century increasingly developed their presence in West Africa—after all, Portugal already had a strong maritime presence as traders between North Africa and Europe via the Atlantic Ocean.

The Portuguese presence in Africa, West Africa in particular, expanded during the 15th century following the exploration of lands further south down the West African coast. This was facilitated by the development of Portuguese colonies in the Cape Verde Islands in the 1450s, a project financed by Prince Henry the Navigator. The son of King John I of Portugal, Prince Henry’s ventures were motivated by the desire for trade expansion, the legend of the Christian king Prester John, and the prospect of spreading Christianity to new converts. While Henry rarely went to see himself, he invested heavily in the early voyages of discovery that earned him his nickname.

Once the Portuguese made it past India and encountered the Maldives, they most likely recognized cowries as the highly prized shell of West Africa. From 1515, the Portuguese began to bring a steady stream of cowries to the Bight of Benin, which was eventually used as currency to buy enslaved Africans. Cowries, people, gold, tobacco, alcohol, sugar, and textiles all changed hands in the Transatlantic Slave Trade, of which Portugal was an instrumental participant.

Indian Ocean and Atlantic Worlds Collapse

The Portuguese were the first Europeans to establish themselves in the Indian Ocean, and they would soon be followed by the Dutch, and subsequently the English, French, and Spanish. While these colonial powers were establishing their commercial and political presence in the Indian Ocean, they were simultaneously destroying and constructing new worlds across the Atlantic in the Americas.

Once the dust had settled on the dismantling of indigenous American socio-political systems, the Americas became ripe environments for the Portuguese and Spanish to replicate the cash crop system they had employed in West African islands since the 15th century. However, this time would be on a much larger scale. The Portuguese had commercial interests around the world, and the commodities produced in the Americas through enslaved labor from West Africa disrupted existing trading relationships in the Indian Ocean.

For example, sugar grown in Portuguese-ruled Brazil by enslaved West African labor would be brought as far as China, in addition to ivory, gold, and other commodities sourced from Portuguese colonies. These would be exchanged for porcelain, silk, and other Chinese goods.

The Portuguese and Spanish colonization of the Americas developed links between the Americas and Asia in many ways, but particularly in the form of cuisine. Peppers, tomatoes, peanuts, and potatoes were all brought to ports in Southeast and East Asia, where they became staple foods. In one case, the introduction of ‘exotic’ foods such as potatoes into China even helped decrease mortality, leading to a population boom during the Ming Dynasty (Wang, p. 99).

Portugal’s Impact on Indian Ocean Trade

The Portuguese also dramatically changed the landscape of Indian Ocean trade by enforcing a trade pass known as a cartaz that could only be administered by the Portuguese. They were mainly registered in Goa, which became the capital of the viceroyalty of Portuguese India in 1530. Being found by a Portuguese ship without a cartaz could result in the confiscation of cargo, burning of ships, or in some cases, the death of its crew members. The cartaz system allowed the Portuguese to control and regulate maritime trade, a major departure from centuries of unmonopolized trade in the Indian Ocean. However, Portuguese dominance of the Indian Ocean trade would be challenged by the Dutch from the 17th century.

Grotius and the Freedom of the Seas

The presence of Portugal in the Indian Ocean trade network would also have an effect on early modern law. At the beginning of the 17th century, Dutch traders announced their presence in the Indian Ocean and challenged Portuguese dominance of the trade network.

In 1603, a Portuguese ship, the Santa Caterina, was captured by the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in the Singapore Straits. Nearly all of its cargo was stolen. Portugal claimed that the maritime straits were under their jurisdiction due to their control of Malacca. Thus, according to Portugal, the actions of the VOC were illegal. To defend themselves, the VOC hired Hugo Grotius, a prominent philosopher, political theorist, and lawyer.

Grotius posed a challenge to the Portuguese cartaz system and events of the Santa Caterina fleet by declaring the sea as ‘mare liberum,’ a concept known in English as freedom of the seas. This stated that the ocean could not be under the jurisdiction of any one country or empire because the sea itself was international territory. All regions were free to trade in it openly. This would create the foundation for what would become international maritime law in the early modern period.

From Europe to the World

Portugal, a country the size of the US state of Maine, was able to disrupt a long-established trading system in the Indian Ocean. Backed by a strong fleet, a tradition of commercial expertise, and enough capital to fund trading missions to India, Portugal became a commanding force in the Indian Ocean.

Further, Portugal helped streamline the flow of objects from Asia into Europe, connected products and people to both Europe and the Indian Ocean, and even helped shape international law. Portugal left a lasting legacy in both the Indian and Atlantic oceans as well as the modern world.

Sources

Disney, A. R. (2009). A History of Portugal and the Portuguese Empire: From Beginnings to 1807. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hancock, J. F. (2021). Spices, Scents And Silk: Catalysts Of World Trade. Cab International (Centro Internazionale Per L’agricoltura E Le Scienze Biologiche).

Heath, B. (2016). Commoditization, Consumption and Interpretive Complexity: The Contingent Role of Cowries in the Early Modern World. Presented at Society for Historical Archaeology, Washington, D.C.

Lains, P. (2024). An Economic History of the Iberian Peninsula, 700–2000. Cambridge University Press.

Wang, Q (2015). Edward. Chopsticks: A Cultural and Culinary History. Cambridge University Press.