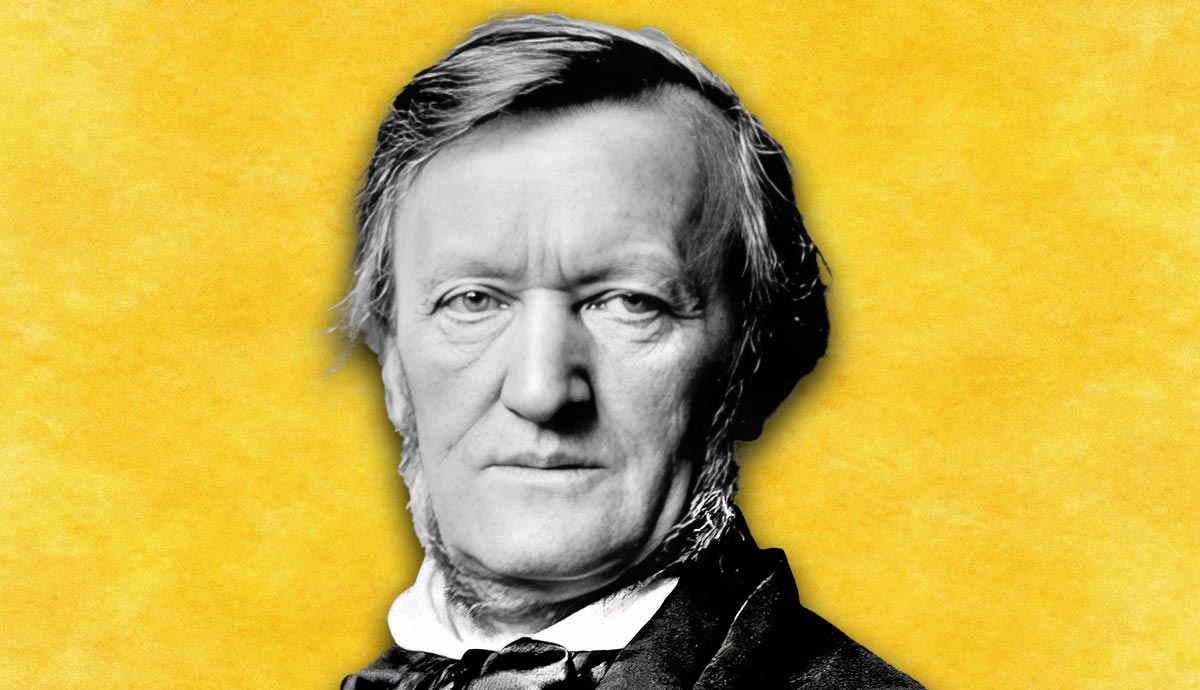

Few composers in history have had as widespread and controversial an influence as Richard Wagner. Eventually celebrated as the genius behind the music and libretti of works whose impact spread beyond the opera world to inspire poets and painters, Wagner struggled for many years to find an audience. He spent many formative years in exile following his revolutionary action, developing theories about art and society that were as seismic in their impact as his music.

Richard Wagner’s Early Years

Richard Wagner hailed from Leipzig, Germany. In the 18th century, it had been the home of J.S. Bach, who wrote many of his most celebrated works while employed at St. Thomas Church. Leipzig would also be the source of the Bach revival in the 19th century, when another native of the city (and a composer Wagner came to see as a great rival), Felix Mendelssohn, conducted Bach’s St. Matthew Passion oratorio.

Born in 1813, Wagner’s early life was dominated by passions for the theater and the music of Ludwig van Beethoven. His immersion in theatrical life came through his stepfather, Ludwig Geyer, an actor and playwright, who married Johanna Wagner when her son, Richard, was just a few months old. Wagner grew up believing, erroneously, that Geyer was his real father and that he was Jewish.

Despite an early education in music and theater, Wagner’s first attempts at composing operas were fairly fruitless. Die Feen (1833) and Das Liebesverbot (1836) were in the Romantic vein popular at the time, but Wagner quickly discovered the unpredictability of the opera world, where employment posts were fleeting and debts racked up all too easily.

Das Liebesverbot is notable because Wagner wrote it while working in Magdeburg, where he fell for and married the actress Minna Planer. This marriage, however, was also to be an education in unpredictability and tempestuousness.

Now living a peripatetic life, traveling between appointments in various centers of music, Wagner built up experiences that shaped his later ideas. In Paris, struggling to make a name for himself amidst the glitzy productions of successful French composers, Wagner formed strong opinions about the irreconcilability of commerce and art, and about French people.

He wrote articles and short fiction to get by. The story A Pilgrimage to Beethoven distills his ideas about the French capital as a place of greed and philistinism, where even Beethoven’s greatness is ignored.

At this time, Wagner also began to conceive anti-Semitic notions about the supposed dominance of Jewish people in Paris’s operatic circles. For Wagner, this was part of the reason that contemporary opera was all commerce and no art—and, of course, this must be why he struggled to get his operas staged.

Actually, Wagner was being disingenuous. The Jewish composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, one of the most successful opera composers of the 19th century, lent strong support to Wagner, enabling him to stage his third opera, Rienzi, in Dresden in 1842.

1848-49: A Turning Point

Wagner was still in Dresden in 1848, a pivotal year across Europe. After moving there in 1842, he had composed The Flying Dutchman and Tannhäuser, works which showed the beginnings of a departure from his early style. His art was evolving. However, for Wagner, art and revolution went hand in hand, and in 1848/1849, he got the chance to put his principles into action.

Throughout Europe, a wave of revolutions broke out whose causes could be traced to the French Revolution of 1789, with its demonstration of the ability of ordinary people (what Marx would, in 1848, call the proletariat) to rise up against institutions such as the monarchy and aristocracy and claim democratic freedoms.

Following the French Revolution, aspirations to create freer and more just societies were brewing all over the continent. In Germany, these aspirations were focused on the unification of the states then known as the German Confederation into one nation.

Wagner, a fervent German nationalist, also passionately believed in the revolutionary call for democracy, feeling that he had been treated unjustly in the hierarchic world of opera, where aristocratic patronage seemed to be essential to success.

He wrote articles in Dresden’s left-wing newspaper and mixed with figures such as the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin. When violence broke out in May 1849, Wagner was a prominent instigator, and a warrant for his arrest was issued. He consequently spent the next 12 years in exile, heading to Zurich in Switzerland.

This was a turning point for Wagner because, in exile, he gained two things. Firstly, the notoriety that made him a popular cause for fellow composers such as Franz Liszt to take up (Liszt defiantly staged Wagner’s next opera, Lohengrin, in Weimar in 1850), and, secondly, the space to undertake profuse writings about his theories on art.

The Art-Work of the Future

In 1849 and 1850, Wagner wrote essays such as Art and Revolution, The Art-Work of the Future, and Opera and Drama. Contemporary opera was, as he had complained before, too commercialized, and this prioritization of money, above all, damaged opera as an art.

Looking back to Ancient Greek theater, Wagner dreamed of a Gesamtkunstwerk in which all the arts—music, poetry, dance, painting—would come together. Operas would no longer be structured around one or two show-stopping arias, when the audience would leave off their private chatter to listen in awe to the diva of the hour. They would be sung through; every element of the music meticulously considered to complement the libretto, and vice versa.

The music, too, would be like nothing anyone had heard before. Zukunftsmusik, or “music of the future,” was a term Wagner’s detractors were already using against him by the 1850s. The meaning of the term varied depending on who was using it. Zukunftsmusik could refer to Wagner’s innovation of techniques such as the leitmotif (a musical phrase which corresponds with a character or idea, woven throughout the drama) and endless melody, in which musical phrases do not reach a cadence, or resolution, but continuously overlap, unsettling the harmonic progressions on which music was traditionally constructed.

Endless melody was one of the reasons Wagner’s detractors found his music unpalatable, even offensive. To his supporters, it was a necessary step beyond the popular insistence on catchy melodies, which had led to operas in which second-rate libretti were paired with scores containing a handful of tunes which audiences could hum to themselves afterwards.

In the 1850s, Wagner sketched out works—initially called music dramas, to emphasize the union of art forms he hoped to achieve—which put these theories into practice, and would become his best-loved works: Tristan and Isolde and the Ring cycle.

He also wrote the essay Jewishness in Music, a diatribe giving full rein to his anti-Semitic beliefs. In the essay, he not only suggested that Jewish composers pandered to commercialism, but that German-Jewish composers, such as Mendelssohn and Wagner’s former supporter Meyerbeer, could never write truly “German” music.

Published under a pseudonym, the essay was supposed to be considered objectively, not associated with Wagner personally, but its motivations could hardly have been more personal. Wagner’s views were a combination of the casual, unchallenged prejudice of his time and a bitter hatred amounting to persecution mania, stemming from artistic frustration and rejection, which found an all too easy target.

Richard Wagner and King Ludwig II of Bavaria

Given Wagner’s antipathy for the practice of aristocratic patronage and commitment to meritocracy (an artistic hierarchy based solely on artistic genius), it is ironic that his return to Germany and triumphant staging of his mature works came about thanks to a monarch.

King Ludwig II ascended to the throne of Bavaria aged 18, and was already what was coming to be known as a Wagnerite: a devotee of Wagner’s music dramas and writings. His offer to patronize Wagner, in 1864, came at an ideal time.

The 1850s had seen the composer’s music and theories surge in popularity. He went to England in 1855 and conducted concerts in front of Queen Victoria. This period was also intellectually stimulating, as he elaborated his libretto for Tristan and Isolde by combining the original Arthurian legend with the pessimist philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer.

At the same time, the decade had also been full of personal drama. Wagner’s marriage to Minna was buckling under the pressure of their exile and dire finances, as well as his infidelity. His infatuation with Mathilde Wesendonck, whose husband helped to financially support Wagner, inspired much of Tristan and Isolde, which has a love triangle at its center. Minna left Wagner in the early 1860s, though not before the affair with Mathilde had come to a tortuous end.

These personal circumstances, along with the newly completed Tristan under his belt, Wagner welcomed King Ludwig’s overtures. Ludwig’s interest in Wagner was intensely romantic, not merely philanthropic, and it seems that Wagner recognized the ulterior motive and let it pass.

After all, here was a young king, blessed with more money than he could ever reasonably spend, offering to bankroll all of Wagner’s music dramas and encouraging him to write the story of his life. Titled Mein Leben, the work would take 20 years to write, spanning four volumes and more than a thousand pages. Ludwig would also soon start building Neuschwanstein Castle, which had rooms decorated with murals depicting scenes from Wagner’s works.

Although in his letters to Ludwig, Wagner reciprocated the king’s words of ardent longing, his heart was elsewhere. He had fallen for a woman named Cosima, daughter of Franz Liszt and wife of Hans von Bülow, a prominent conductor who promoted Wagner’s work. In April 1865, just two months before von Bülow conducted the premiere of Tristan and Isolde, Cosima gave birth to Wagner’s child: a daughter called Isolde.

The Ring Cycle and Bayreuth

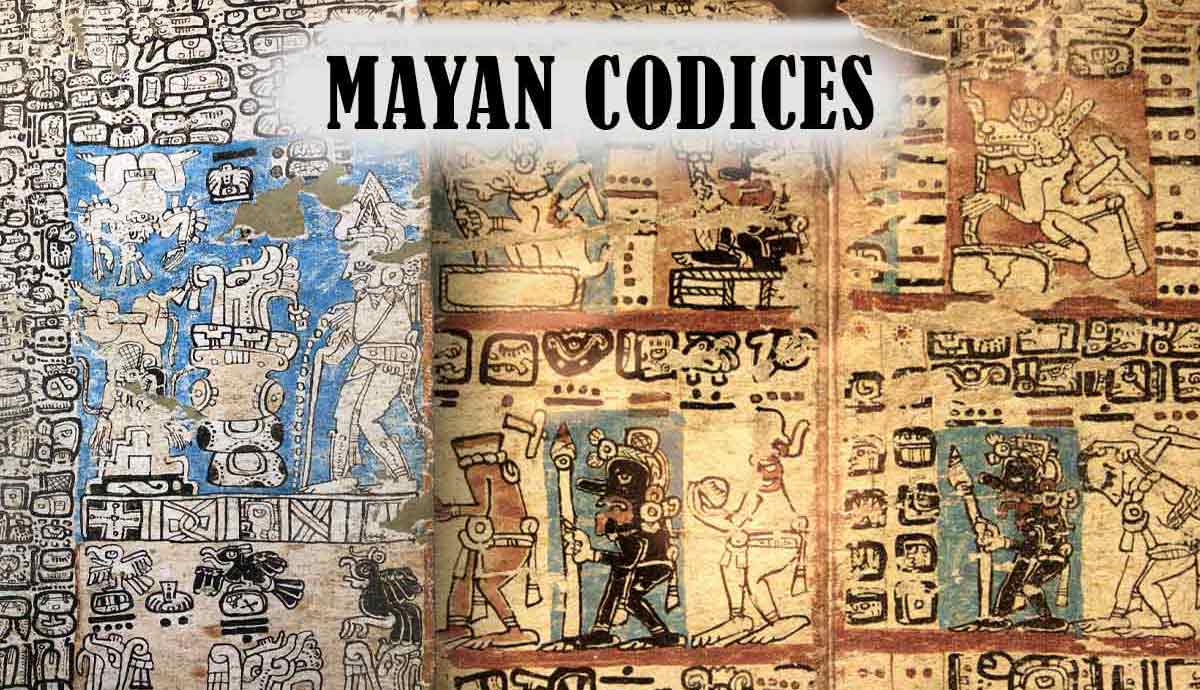

By 1876, Wagner had completed a cycle of four operas which, since the beginning over 20 years previously, he had envisioned as his masterwork. The tetralogy was called Der Ring des Nibelungen (The Ring of the Nibelung) and was based on old Germanic and Norse epics. In line with Wagner’s fervent nationalism and wish for the German states to be unified as one country (and, he hoped, one race), the cycle was meant as a foundational work for the German people.

The first drama, The Rhinegold, sets up the events of the tetralogy: the theft of the mythical gold from the River Rhine, the enslavement of the Nibelung people, and the all-powerful god Wotan, who fashions a ring from the gold.

In the sequel, The Valkyrie, we are introduced to the incestuous siblings Sieglinde and Siegmund, whose child, Siegfried, is destined to be a hero, and Brünnhilde, a warrior goddess who will help save him. The third and fourth dramas, Siegfried and The Twilight of the Gods, show Siegfried’s quest for the ring, Wotan’s vengeance, and Brünnhilde’s self-sacrifice.

Along with these dramas, conceived as total works of art in which music, words, and visual art were perfectly blended, Wagner had the idea of building a theater solely for performances of the Ring. Financed by Ludwig II, the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, or festival theater, was purposely built in an out-of-the-way village, rather than in one of the major centers of German music.

Every aspect was designed to enhance the performances of Wagner’s work, from the way the sound reverberated in the auditorium to the hidden orchestra pit and wedge-shaped seating arrangement, which gave every audience member an equal view of the stage.

Work on the theater at Bayreuth began in 1872, with the intention of opening in time for the premiere of all four works in the Ring cycle. Wagner did not quite get his way—the first two parts of the cycle were premiered individually a few years earlier—but when Bayreuth opened in 1876, its first performance was the premiere of the Ring in full.

In 1882, an annual festival having been established at Bayreuth, it hosted the premiere of Wagner’s final music drama, Parsifal. At last, he had found a way to avoid the jostling and negotiations with the music industry that had so infuriated him. With Bayreuth, he could stage his works exactly as he liked, keeping all the revenue for the continuation of the theater, and bringing audiences to him rather than condescending to try and attract them.

The Case of Nietzsche

The Ring and Wagner’s other works were steeped in philosophy, from Schopenhauer to mysticism and Christian theology. In 1868, he met a young, up-and-coming philosopher, who would influence Wagner and be influenced by him in turn: Friedrich Nietzsche.

1872’s The Birth of Tragedy chimed with Wagner’s interest in Ancient Greece as the ideal civilization, with Nietzsche meditating particularly on music in envisioning his influential dichotomy between the Apollonian (order and form) and Dionysiac (chaos and disorder). Nietzsche wrote the book at the instigation of Wagner (and Cosima, now married to the composer), and it specifically name-checked the composer’s works as modern embodiments of the Greek ideal.

Nietzsche’s relationship with the Wagners was close and personal. It is a matter of speculation whether Nietzsche was more enamored with Richard or Cosima. He certainly wrote about having fallen in love with the latter, but was this an effect of her closeness to the composer? Commentators from Sigmund Freud onwards have read a certain amount of repression into the philosopher’s relationships with men. Nietzsche appears to have idolized Wagner, who, as with Ludwig, encouraged and probably quite enjoyed the admiration.

By 1888, though, Nietzsche had repudiated Wagner—not privately, since the composer had died back in 1883 and their relationship had cooled before then—but publicly. In the essays The Case of Wagner and Nietzsche Contra Wagner, the philosopher took a radical new stance against his former idol, albeit one which many readers shared.

By the fin de siècle, many saw Wagner and his music as dangerous, its endless melody and lack of rhythm exerting a hypnotic effect on listeners, leaving them open to pernicious suggestions by this dictator-like figure pulling all the strings.

Nietzsche continued to admire some things about Wagner, but no longer saw him as the redeemer of German music. Instead, he was a sign of decadence and moral decline. For Wagner’s supporters, Nietzsche’s diatribes would be invalidated by the fact that the philosopher succumbed to a mental breakdown just a year later, but the posthumous battle over the significance of Wagner in German culture had begun.

Wagnerism: From Decadent France to Nazi Germany

The cult of Wagner, after his death in 1883, went far beyond what he could have imagined—or, maybe, it was exactly the scope he had always dreamed of. Wagnerism spread across Europe, like a virus, some said, infecting just about every art form, from poetry to painting to architecture. His terminology around “music of the future” infiltrated beyond the arts, as people at the end of the 19th century envisioned a politics of the future, inventions of the future, men and women of the future, and so on.

In late-19th-century France, his name was nearly inescapable in artistic circles. Painters such as Van Gogh and Cézanne, poets such as Mallarmé, and novelists such as Proust all aimed for Wagnerian effects in their work. Championing the German Romantic in the wake of the Franco-Prussian War was an act of counter-cultural protest for many of these artists. But three decades into the 20th century, Wagner ceased to be an anti-establishment figure.

What had been latent and not widely recognized in Wagner and his works soon rose to the surface and became indelibly associated with him. Writings such as Jewishness in Music and his private anti-Semitic comments had been known only in a few circles during his lifetime, and the idea that his dramas contained anti-Semitic caricatures was not yet a common interpretation.

When the Nazis came to power, however, they celebrated Wagner as the pinnacle of German culture, thanks to his portrayal in the Ring of what they saw as the pure essence of the ancient German spirit. Music by Jewish composers was suppressed, and the Bayreuth Festival flourished. Winifred Wagner, who was married to Richard’s son Siegfried, was a personal friend of Adolf Hitler and often welcomed him to the Wagner residence at Bayreuth.

This is why Wagner has remained a controversial figure. The question of performing his music in Israel is still highly contested. Meanwhile, the Bayreuth Festival continues to be a mecca for devotees, with an intimidatingly long waiting list for tickets.

His ambition to transform music and drama completely was fulfilled, with his work still striking audiences as avant-garde and challenging. His Ring cycle was a clear influence on later epics such as Lord of the Rings, and the interest in mythology, which he helped revive, is thriving today.

Some argue, therefore, that Wagner’s influence has been so broad and varied (he has even been reclaimed by Jewish artists, for instance) that he need not be solely associated with the darker side of his legacy. For others, he remains an eternally contentious figure.