Throughout the centuries, the word “Teutonic” has had multiple meanings. Originally, it was just the name of a Germanic tribe that fought a bloody war with the Romans. After this encounter, the word began to be used to describe the ferocious Germans more generally. In the Middle Ages, a knightly order bore the name, and the word Teutonic came to represent their chivalric values. In the modern era, the word Teutonic still holds a place in the lexicon, reflecting the enduring legacy of an ancient tribe of barbarians on the outskirts of Rome.

Who Were the Teutones?

About 3000 BCE, Indo-Europeans migrated from their home along the Pontic-Caspian steppe, reaching what is now modern-day Germany. Over the following millennia, they divided into various tribes, all of which shared similar cultural and linguistic identities. One of these tribes was the Teutons, who inhabited the region of northern Europe on the Jutland peninsula. Some time in the 2nd century BCE, the Teutons and a nearby related tribe, the Cimbri, migrated southeast. The reason for this migration is a matter of debate. It could have been due to flooding, famine, or competition from other tribes. As they journeyed, the combined Teuton-Cimbri migration displaced some of the Celtic tribes they encountered, including the Boii and the Scordisci. They continued south until they reached the Danube River, where they displaced the Taurisci, another Celtic tribe. However, the Taurisci were an ally of the Roman Republic, setting the stage for a clash between the Teuton-Cimbri and Rome.

For the most part, historians and scholars believe that the Teutones were Germanic, a distinct ethnic and cultural group from the Celts. However, there is some debate over this. The name presumably originates from the Proto-Indo-European word tewteh, meaning “tribe” or “people.” Early writers labeled them as Celtic, although these Roman chroniclers did not bother to make a distinction between Germanic and Celtic, which only adds to the confusion. It is possible that they were a primarily Germanic tribe, but incorporated Celtic elements and members into their society as they migrated.

The Cimbrian War

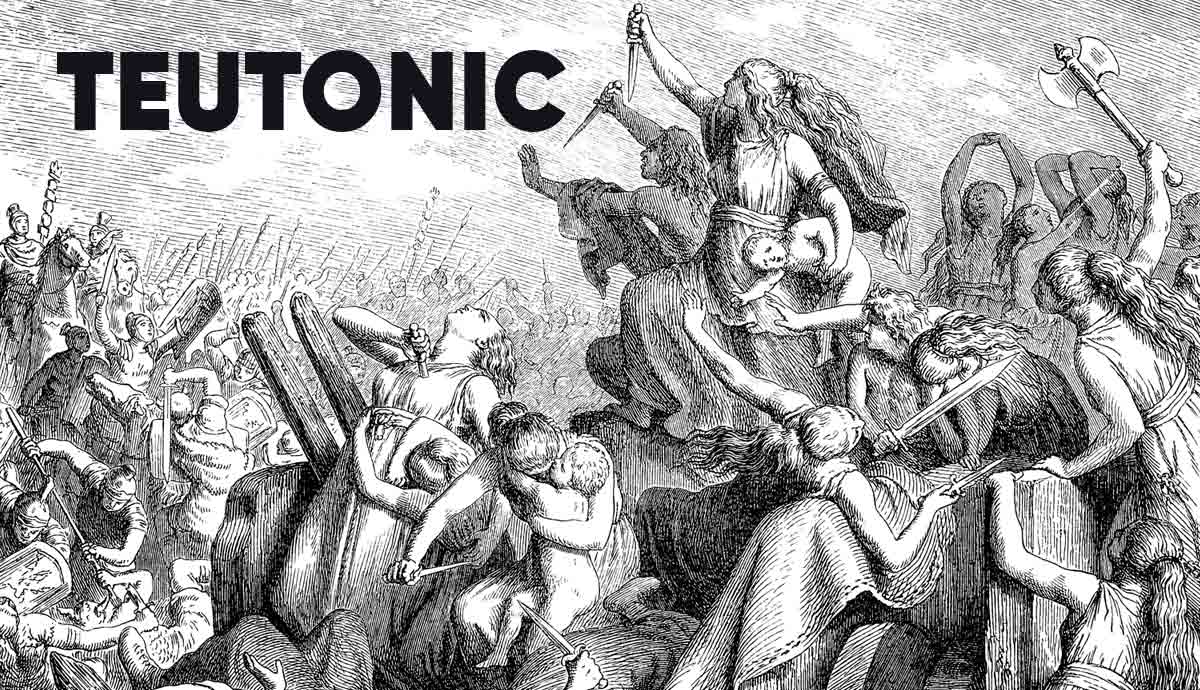

In 113 BCE, the Teutones and the Cimbri, along with other Germanic and Celtic tribes such as the Tigurini and the Ambrones, marched into Gaul and attacked the local tribes and clans, some of whom were allied with Rome. In response, the Roman Republic sent the consul Gnaeus Papirius Carbo with an army north to deal with the situation. They wanted a show of force to intimidate the invaders, which initially worked. The Germans gave in to Roman demands, but then Carbo bit off more than he could chew. He attempted to ambush the Teutones and Cimbri, likely a ploy to gain military glory. Enraged by the treachery, the Teutones attacked the Romans, smashing their army, killing tens of thousands in one of the worst disasters in Roman military history. Carbo managed to escape but was placed on trial for his failure and committed suicide rather than face exile and humiliation. With the way open, the Germanic tribes had a clear path to Rome itself.

Instead of taking advantage of this situation and marching on Rome, the Teutones and Cimbri turned west and entered Gaul. They continued to roam, gathering tribal groups in the area to their cause, and causing havoc among those who would not submit to them. The Romans sent other armies, but the Teutones and the Cimbri, along with their allied tribes, smashed them as well. Wanting to end the threat, the Romans sent the largest army since they fought Hannibal.

In 105 BCE, they met the Germans on the field at the battle of Arausio. Once again, the Teutones and their allies broke the back of the legions sent after them, inflicting one of the greatest defeats in Roman history. After the battle, the tribes split, with the Cimbri marching against Hipania and the Teutones remaining in Gaul. No one knows why they did this, or why they didn’t march on the now vulnerable Rome.

Desperate, the Romans recalled Gaius Marius, a successful military leader and former consul, who was reelected under extraordinary circumstances to take command of the war. He changed recruiting rules to raise a new army to meet the threat. Under Marius’ leadership, the Roman policy of allowing only landowners to serve in the military was abolished, paving the way for a professional standing army, a hallmark of Roman success in later centuries. With his new army, Marius faced the Teutones at Aquae Sextiae in 102 BCE. He crushed the Germans and captured their king, Teutobod. The next year, the Cimbri were also destroyed, ending their threat once and for all.

The Teutons Following Defeat

After the crushing defeat at Aquae Sextiae, the Teutones’ power was broken. Though some Teutones were taken as slaves and later participated in the Third Servile War, they had no major direct impact on Roman history. The remnants of the Teutones and the Cimbri that remained in Jutland continued to exist, but were eventually absorbed by the Jutes and Saxons centuries later, ending their unique cultural identity. They would have remained a footnote in history, a threat to Rome that was eventually put down, if it were not for a linguistic trick.

Though the city of Rome was never directly threatened by the Teutones or the Cimbri, they gave the Roman Republic and later empire nightmares about giant warriors from the north, savage barbarians who were poised to descend on civilization, slaughtering everything in their path. This paranoia played a significant role in Julius Caesar’s campaign in Gaul, decades after the Cimbrian War, and during the later wars under Emperor Augustus. For the rest of Roman history, these Germani, as they were collectively called, were always on the edge of Roman territory, sometimes acting as adversaries, sometimes allies. Migrations in later centuries caused the Germani to descend on the dying Roman Empire, their actions being a major contributor to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire.

Although they were no longer a threat, the Teutones had a disproportionate influence on the Roman psyche. Since the encounter with the tribe, the name Teutones, sometimes rendered as Teutons, became used interchangeably with the word Germani. After Rome fell, the Catholic Church assumed much of the responsibility for maintaining society, and the Church’s language, Latin, became the lingua franca of Europe. By the 8th century or so, Teuton became conflated with the word “Theodisc,” which was a vernacular group of German languages in the eastern portion of Charlemagne‘s empire. Over time, Teuton became the medieval Latin word for German, the language and ethnic group, not a political entity.

The Middle Ages and Modern Day

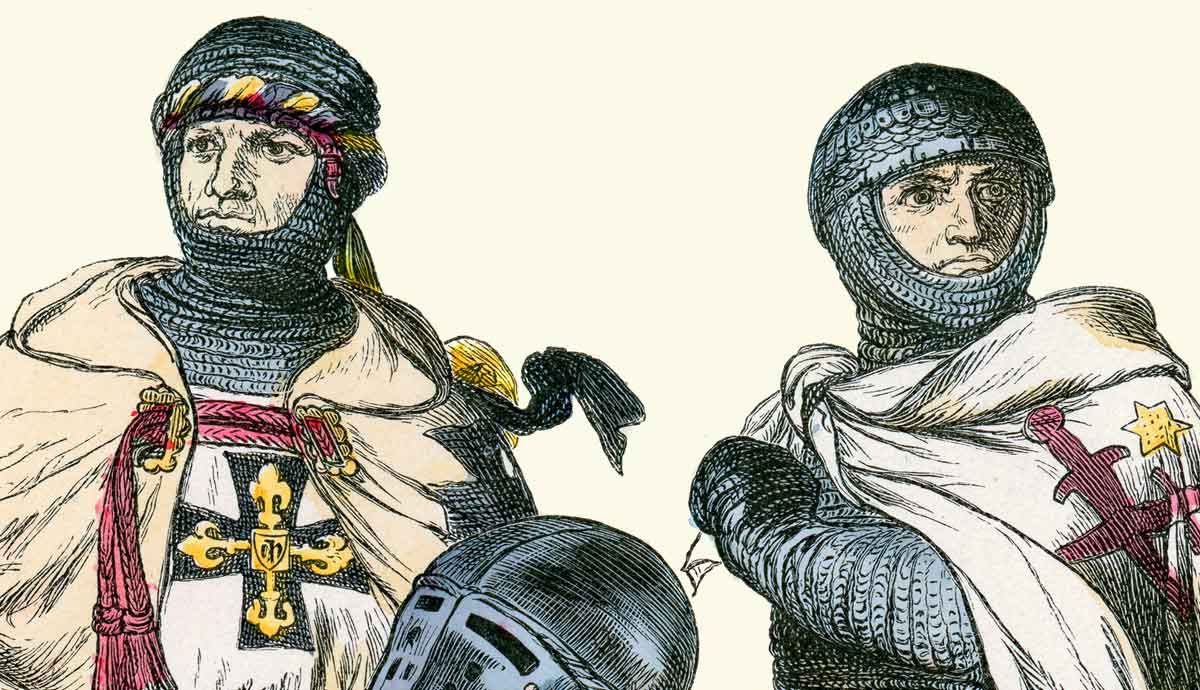

During the Crusades, a group of German merchants and knights founded a hospital in Acre in the Holy Land and dedicated the building to the Virgin Mary. In 1198, the group was transformed into a militant Holy Order, organized along the same lines as the Knights Templar. The Germans referred to their order as the Brethren of the German Hospital of Saint Mary. In Latin, this was translated as Fratres Domus hospitalis sanctae Mariae Teutonicorum. Their name was shortened to simply the Teutonic Knights, and they spent the next few centuries campaigning in the Holy Land and later along the Baltic coast, fighting the Church’s enemies. They would establish states in Prussia and Livonia. Through the foundation of the Prussian state, they heavily influenced European history in much later centuries. The Teutonic Knights were related to the original Teutones geographically, as both were from Germany. Their fame solidified Teuton as a word to describe the Germans in general.

Even after the Middle Ages and the dissolution of the Teutonic Knights, the word Teuton continued to be used as a descriptor. In the English Language, the word “German” was and still is used to describe the ethnic, cultural, and linguistic group from Central Europe, but “Teutonic” was still used as an adjective to describe qualities and stereotypes of the German people. For example, many writers attribute the stereotypical orderliness of German culture to their “Teutonic nature.” This is often done as a pejorative and was commonly used in propaganda during the World Wars. Ironically, these Teutonic traits, such as orderliness, discipline, and respect for authority, were rarely associated with the actual Teutones, a group the Romans had nothing but scorn for.

Today, the term has fallen out of favor and is seen as archaic. Still, when there is a need to describe the German lands in an evocative way, Teuton is ready to fill the need. The metal band Accept named a hit song “Teutonic Terror,” where they fight enemies and “give ’em the axe!” The hit strategy game Age of Empires II features many civilizations from across the medieval world. The faction that represents Germany is called the Teutons, with a unique unit of Teutonic Knights being one of the most durable and hard-to-kill in the game. These are just a few ways that the memory of the Teutons survives into the modern age. Not a bad legacy for one of many Germanic tribes on the fringes of the Roman Empire.