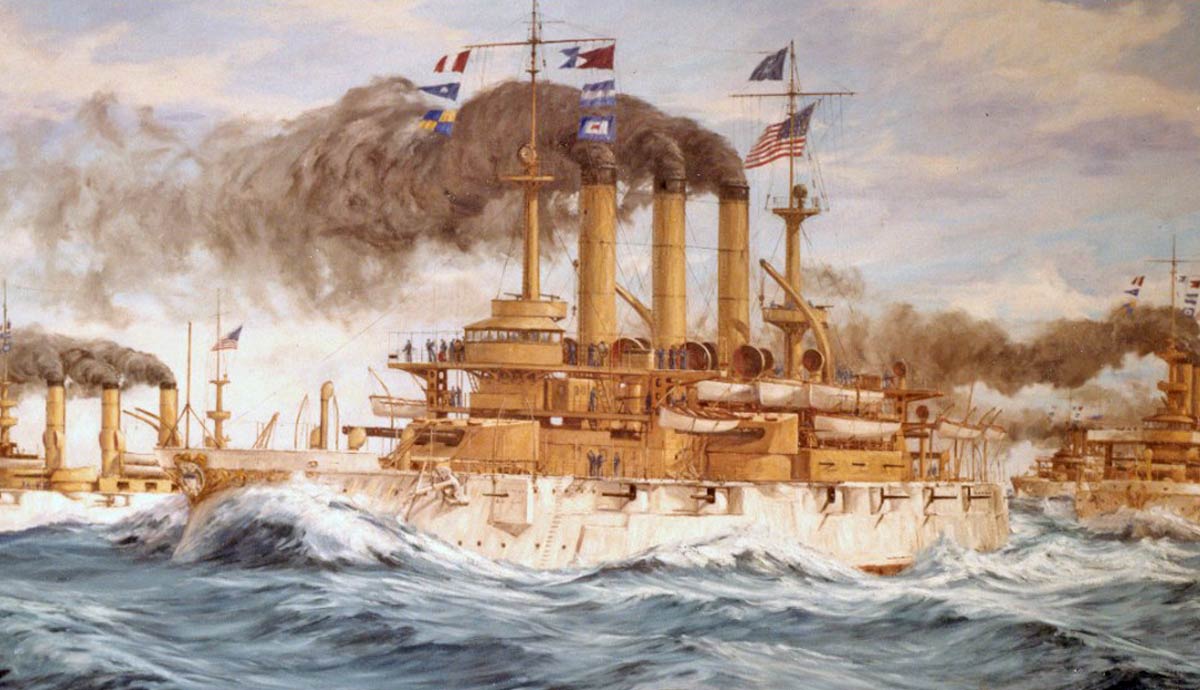

From 1907 to 1909, President Theodore Roosevelt sent a fleet including 16 capital ships around the world as a demonstration of American power. This so-called Great White Fleet voyage helped solidify the United States’ reputation as a prominent naval power at the beginning of the 20th century. It also gave the US Navy valuable experience in fleet operations.

Roosevelt’s Belief in Naval Power

Ever since he was a young man, Theodore Roosevelt had always expressed an interest in American naval power. He had long been a proponent of the belief that the United States needed to project military force abroad in order to display its strength. As Assistant Secretary of the Navy, he established a close relationship with Admiral Alfred Thayer Mahan, who was a major proponent of the idea that naval power defined a nation’s capabilities. Roosevelt incorporated Mahan’s ideas into his policies during his presidency.

When Roosevelt was inaugurated following the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901, the US Navy had 160 warships available for combat operations. Senior politicians and admirals had ambitions for an even larger fleet. Roosevelt had been impressed by the US Navy’s performance against the Spanish and he hoped to demonstrate to other European countries that the United States was a world power. Additionally, there were tensions between the United States and Japan after the Japanese blamed Roosevelt’s mediation of the 1905 Treaty of Portsmouth to end the Russo-Japanese War for denying them reparations from Russia. The administration believed that a visit by the US fleet bearing gifts would cool down some of the anger from the riots.

Naval expeditions to show strength were not a new concept in American history. In 1838, several American vessels sailed across the Pacific as part of the Exploring Expedition to conduct scientific research. This expedition, however, would be one of the largest in American history to date in terms of tonnage. It provided an opportunity for American sailors to conduct fleet maneuvers and practice long-distance sailing procedures.

Preparing the Fleet

While the navy had a large number of warships available for the expedition, it faced some major logistical challenges. There was a lack of coal stations available, meaning that the fleet would have to stop at British coal stations on its voyage. Additionally, some of the ships in the fleet were not fully seaworthy by the scheduled date of departure. Nonetheless, Rear Admiral Robley D. Evans, the first commanding officer of the fleet, was determined to sail on his scheduled date and contracted several colliers (ships designed to carry coal) to join his ships. Evans, an experienced veteran of the Civil War and Spanish-American War, had the confidence of much of Washington to accomplish his mission.

The fleet was scheduled to leave Hampton Roads in Virginia in December 1907. Every ship had been built after the war against Spain, but all were technically outdated because they were pre-dreadnoughts. Nonetheless, they packed a potent punch and could carry sufficient supplies for the voyage. 16 capital ships were part of the fleet, led by the USS Connecticut, the lead ship of the Connecticut class of pre-dreadnoughts. The battleships were organized in four divisions, all led by a rear admiral, with auxiliary ships bringing up the rear. During the voyage, some ships were detached for additional duties.

Roosevelt was determined to see the expedition sail, even against congressional opposition. Maine Senator Eugene Hale, a fellow Republican, announced he would oppose any funding for the fleet, arguing it was a waste of money. Roosevelt responded by saying that the fleet would sail anyway.

The Fleet Sets Sail

On December 16, 1907, the USS Connecticut led the first ships of the Great White Fleet out of Hampton Roads. The fleet’s departure was a memorable sight as thousands of onlookers gathered to watch. President Roosevelt himself watched from the presidential yacht Mayflower, remarking, “Did you ever see such a fleet and such a day?” The ships sailed several hundred yards apart from one another, maintaining a tight formation. Admiral Evans hoped to make good time as the fleet sailed into the South Atlantic.

The fleet’s plan was to sail around Cape Horn and get to San Francisco by the spring of 1908. Despite the notorious winds and storms routinely striking the cape, enough sailors had gone around it so that future crews could avoid the worst conditions in the area. Despite no pilot showing up to help the fleet through the Magellan Strait, Admiral Evans ordered the fleet to sail. No ships were lost or seriously damaged during this passage. In February 1908, the fleet arrived in the Chilean port of Valparaiso and continued northward to Callao, Peru.

Part of the voyage’s purpose was to train officers and crews in large fleet maneuvers. Before entering Callao’s harbor, Admiral Evans ordered the fleet to execute a “gridiron” turn. This involved all the ships in tight formation turning sharply together. After visiting Peru, the fleet continued on to Mexico and arrived at San Francisco on May 6, 1908. The first leg of the trip had been completed successfully.

From California to Manila

From May to July, the fleet steamed up and down the Pacific coast, attracting massive crowds along the way. When it arrived at Seattle, some 400,000 people gathered to watch it enter the harbor. In late May, the fleet returned to San Francisco to prepare for its voyage across the Pacific to the Philippines. At this point, Admiral Evans had fallen ill and had to be replaced by Rear Admiral Charles Sperry. Sperry was a less experienced officer than Evans but was still considered capable enough to carry out Roosevelt’s mission.

When the fleet left San Francisco for the second time in July 1908, its composition had changed slightly. The battleships Maine and Alabama had to remain in port because of engine problems that had bedeviled them on the first part of the voyage. They were replaced by the ships Nebraska and Wisconsin which had been scheduled to return to the East Coast regardless of the Great White Fleet’s scheduled stop. While on the West Coast, 129 men deserted, a relatively low number for the time.

Later in the month, the fleet stopped in Hawaii, at this point a territory of the United States. The major facilities that came to define Pearl Harbor had not been developed yet, so Admiral Sperry could not remain long. The next leg of the trip was the longest stretch without docking. After stopping in New Zealand and Australia, the fleet went on to the Philippines, recently conquered from Spain in the Spanish-American War, and called at Manila.

The Last Leg Home

The fleet’s time in Manila was marred by a cholera outbreak in the city, meaning that all leave was canceled. After a week, Admiral Sperry ordered his ships to sail on to Yokohama harbor in Japan. Roosevelt had insisted the fleet stop there as a courtesy in order to tone down the tensions between the United States and Japan. Japan reciprocated, pulling out all the stops to welcome Admiral Sperry and his crews. After a week in Japan, the fleet split in two, with one squadron headed to Amoy (Xiamen), China, and the rest headed back to Manila.

Relations between the Chinese and the Americans were tense because of the fear that the United States wanted to take control of a Chinese port. While these concerns were justified, since several European colonial powers had obtained concessions in Chinese ports during the latter half of the 19th century, American officers sought to convince Chinese officials that they had good intentions, and no major incidents occurred during the brief stay. On December 1, the reassembled fleet left Manila after performing some battle drills. They stopped in Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and headed through the Suez Canal to the Mediterranean.

Their time in the Mediterranean Sea coincided with a major earthquake off the coast of Messina in Sicily, causing major damage and devastation to the island. Several ships were detached to provide supplies to the victims, including the flagship USS Connecticut. Other vessels were sent to visit different ports in the region as a courtesy call before the fleet went back to Hampton Roads. When the fleet reassembled at Gibraltar, two captains were relieved of duty. On February 22, 1909, the Great White Fleet reentered Hampton Roads after braving severe storms in the Atlantic Ocean.

Aftermath and Legacy

By sailing a major fleet around the world, the United States showcased the ability to project force far from its borders. The expedition was a manifestation of Roosevelt’s Big Stick Policy: the idea that by making a great show of force, the United States would not have to resort to it. He also hoped that the United States would take Great Britain’s place as the world’s predominant naval power, a process that would take place gradually over the first half of the 20th century.

The expedition highlighted important strengths of the navy, such as the sailing proficiency of its crews and low desertion rates. It also exposed some weaknesses. The ships, while all were recently built, were outdated by new dreadnoughts appearing in other navies. The lack of resupply stations abroad meant that the fleet was reliant on resupply from other countries. Additionally, none of the warships got involved in combat while sailing. This meant that some deficiencies were not addressed until WWI.

As the fleet circumnavigated the globe, the first dreadnoughts in the US Navy were undergoing sea trials. The start of the 20th century saw a massive shift in the projection of naval power. More ships were armed with heavy guns and bigger engines. When the US Navy joined the Allied fleet in the North Sea to blockade German ports during the First World War, it was manned by crews who had learned from the Great White Fleet on how to conduct fleet maneuvers at sea far from home.