summary

- Thucydides’ Melian Dialogue: The 5th-century BCE historian recalls a supposed exchange between the Athenian army and the besieged people of Melos during the Peloponnesian War.

- Melian Argument: Melos argues that Athens’ attack on the neutral city is unjust.

- Athenian Argument: The Athenians argue that their superior power gives them the right to pursue their interests at Melos’ expense.

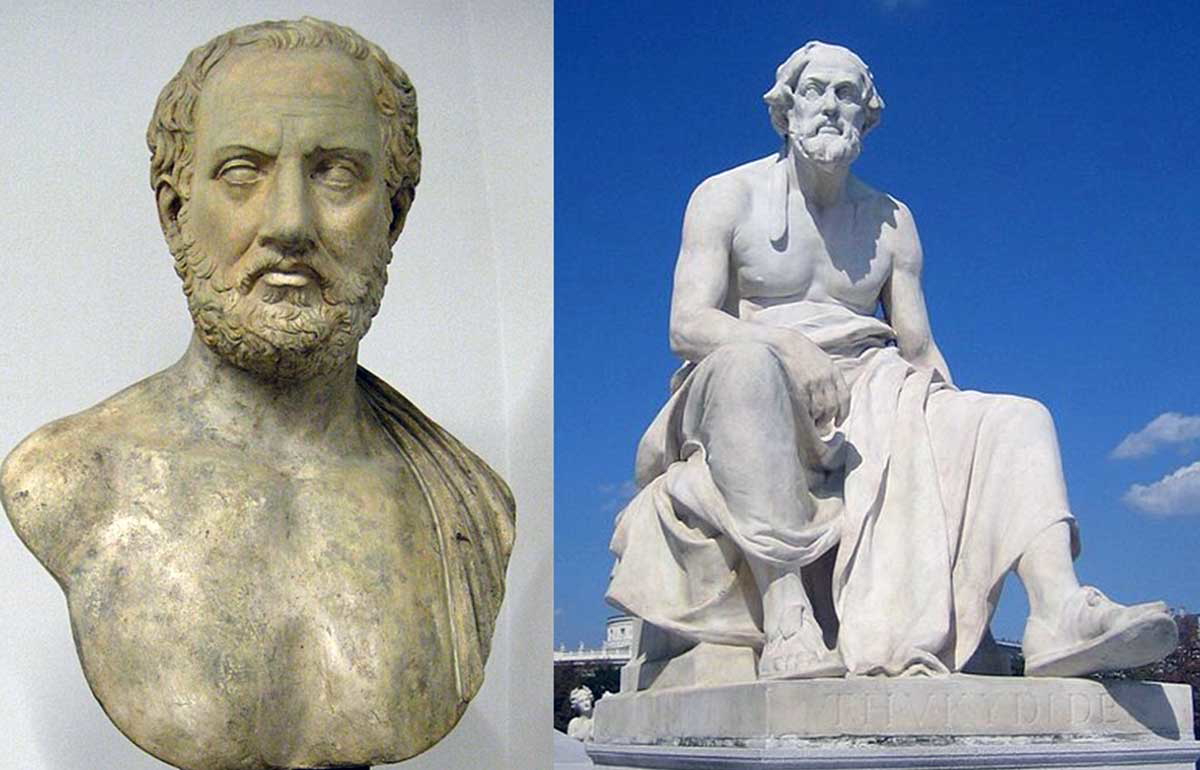

The 5th-century BCE Greek historian Thucydides is often called the father of scientific history. Unlike earlier historians, who based their accounts on legends and hearsay, Thucydides used a historiographical approach for his History of the Peloponnesian War, analyzing the evidence with impartiality. His analysis of the Peloponnesian War raises questions about the nature of international politics that we continue to debate today. One episode, known as the Melian Dialogue, poses the question: Does might make right?

Context of the Melian Dialogue: The Peloponnesian War

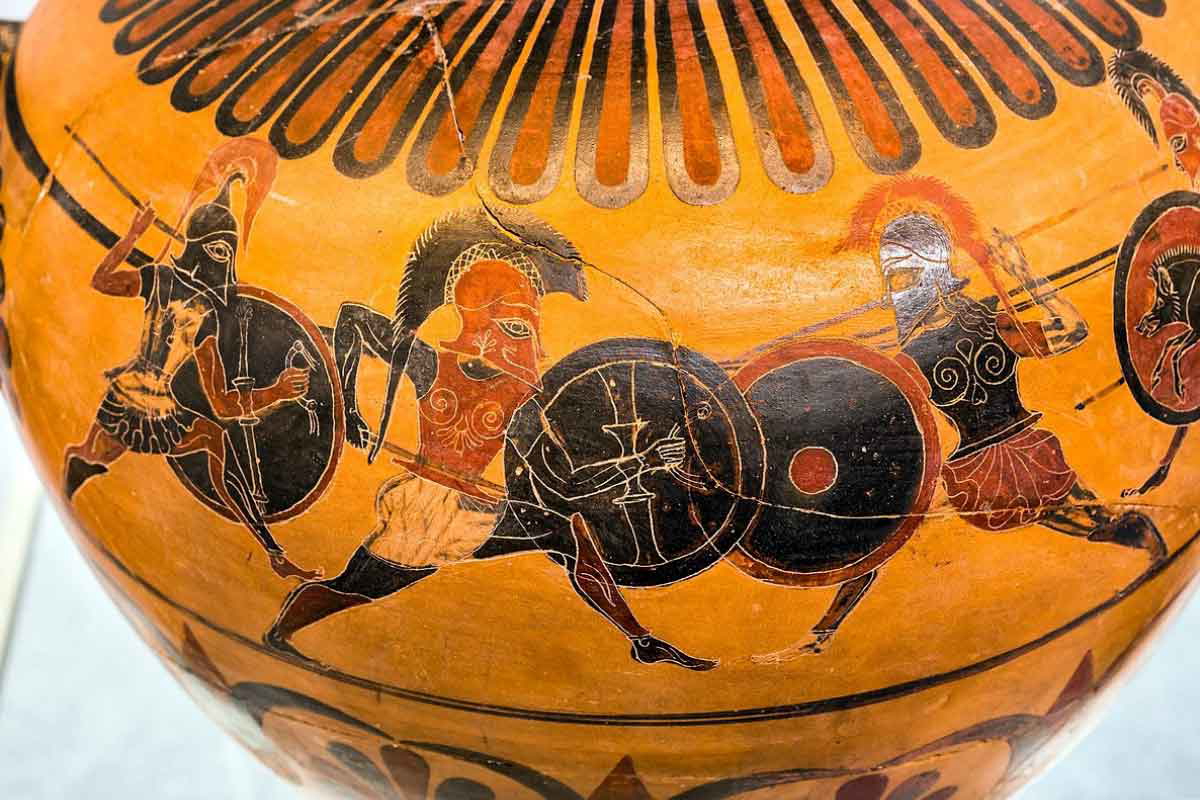

The Peloponnesian War was a conflict that engulfed the Greek world between 431 and 403 BCE. The war was fought between the two most powerful Greek city-states and their allies: Athens and the Delian League versus Sparta and the Peloponnesian League.

The war was characterized by long periods of stalemate. Athens held supremacy at sea, guaranteed by its capable navy, while Sparta enjoyed the military advantage on land, secured by its formidable army of professional citizen soldiers. The war impacted almost every corner of the Greek world, which sprawled across the Mediterranean. For instance, Athenian forces ventured as far West as Sicily, where they suffered a crushing defeat in 413 BCE. Meanwhile, Spartan forces embarked on an expedition to the northeast, where they captured Byzantium in 411 BCE.

In the final phase of the war, between 414 and 404 BCE, the Persians, who had grown wary of Athens’ maritime power, granted Sparta financial support, which enabled the Spartans to build a capable fleet of their own. In 405 BCE, under the skilled Spartan Admiral Lysander, the Spartans sailed to the Dardanelles to cut off Athens from vital grain shipments. The Athenian navy was forced to pursue but was decisively defeated at the Battle of Aegospotami. Without the ability to import food, the Athenians were forced to surrender, and the war ended with the Peloponnesian League victorious.

The Siege of Melos

In the middle of the conflict in the summer of 416 BCE, Athens invaded Melos, an island in the Aegean Sea. The events that would transpire there would be among the most infamous in the war. The Melians, a Doric people, shared ancestral ties with Sparta but maintained neutrality during the war.

Nevertheless, the Athenians demanded that Melos submit and pay tribute to Athens. The Melians, not wanting to give up their political autonomy and freedom, refused. The Athenians besieged the island’s capital city. The Melians surrendered in the winter, but the Athenians showed them no mercy. All the adult men were put to the sword, and the women and children were enslaved. This is sometimes considered an example of ancient genocide.

The Melian Dialogue

Thucydides’ account of these events is heavy with pathos. The Melian Dialogue is given before his account of the siege itself, when the Athenians are trying to persuade the Melians to submit to their power. The Melians refuse, and the dialogue consists of the back-and-forth arguments made by both sides.

The attraction of the Melian Dialogue is that both sides make strong points, but are coming at the debate from fundamentally different ideological perspectives. The debate that unfolds reflects modern political debates over international relations.

The Melian Argument

When confronted by the Athenian ultimatum, the Melians appeal to justice and morality. They tell the Athenians: “We trust that the gods may grant us fortune as good as yours, since we are just men fighting against unjust.” Such an argument speaks to a sentiment that there is a natural sense of universal justice that should underpin relations between nations.

The Melians also present more grounded arguments in terms of cause and effect. They assert that the unjust attack of the Athenians upon a neutral city-state would compel others to react, namely the Spartans, who shared kinship with the Melians and were already at war with Athens. The Melians declared that “what we want in power will be made up by the alliance of the Lacedaemonians, who are bound, if only for very shame, to come to the aid of their kindred.”

The Athenian Argument

In Wassermann’s estimation, “It is a typical aspect of Athenian character that even at this moment of strength, and, as the latter treatment of the reluctant island shows, supreme ruthlessness, the Athenians try not only to conquer, but to convince.” To this end, the Athenians tell the Melians that they need their city for their own purposes, as it was the only island in the Aegean not under their control. They urge the Melians to surrender to their more powerful force in the interest of self-preservation.

From the outset, the Athenians banish all moral sentiments from their arguments, saying to the Melians: “since you know as well as we do that right, as the world goes, is only in question between equals in power, while the strong do what they can and the weak suffer what they must.” In other words, the Athenians have a right to treat the Melians however they wish because they enjoy greater power. It is the argument that might makes right.

“The Strong Do What They Can and the Weak Suffer What They Must…”

The arguments presented in the Melian Dialogue transcend the Peloponnesian War and pose questions about the inherent nature of international politics. The Athenian approach to foreign affairs, which is rooted in security and power, closely mirrors the tenets of realist political thought, for which it has become a case study.

Realist theory supposes that in international politics, there is no moral authority above the state, resulting in anarchy. In this anarchic landscape, all states are motivated by fear and mutual distrust and must therefore seek power and security to safeguard their continued existence. In the words of the realist thinker Hans Morgenthau, a statesman necessarily “thinks in terms of interest defined as power.”

This type of ideology clearly underpins the Athenian argument. W. Julian Korab-Karpowicz asserts that “Since such an authority above states does not exist, the Athenians argue that the only right in the world of anarchy is the right of the stronger to dominate the weaker.” In such a world, the appeal of the Melians to justice matters not, as indeed the Athenians “explicitly equate right with might, and exclude considerations of justice from foreign affairs.”

Realism and the Peloponnesian War

The tenets of realism can be identified elsewhere in the work of Thucydides. His assessment of the cause of the war is often cited as a classical example of realist thought and the balance of power theory. According to Thucydides, “It was the rise of Athens and the fear that this inspired in Sparta that made war inevitable.”

The balance of power theory posits that states ensure their survival by preventing any single state from acquiring overwhelming military power. When one state becomes significantly stronger, the theory predicts that it will exploit weaker neighbors, compelling them to form a defensive coalition.

Evidently, Sparta was concerned with the balance of power in the Greek world. The continued growth of the Athenian empire was perceived as a threat to Spartan security, to other city-states, such as Corinth, and even the mighty Persian Empire, which was motivated to support Sparta due to wariness of Athens’ growing power. These anxieties made a war with Athens “inevitable,” as Thucydides put it.

The Thucydides Trap

Given the universal themes explored in Thucydides’ account of the Peloponnesian War, it is no surprise that it continues to be influential today. American political scientist Graham T. Allison even coined the term “Thucydides Trap”. This relates to the tendency for emerging powers and great powers to go to war, especially when there is a risk that the latter will be displaced by the former. A study conducted by Allison found that out of 16 historical cases in which an emerging power rivaled an established great power, 12 of them resulted in conflict.

In recent years, the Thucydides Trap has attracted interest in discussions concerning the rise of China and the challenge it could pose to the United States as the world’s ruling hegemon.

Athens’ treatment of Melos faced criticism at the time. But the Athenian rhetorician Isocrates stated that it was necessary for Athens to be as brutal as its enemies, citing the massacre committed by the Spartans at Plataea, an Athenian ally, in 429 BCE. They killed the defenders, including a small group of Athenians, and razed the city. The Athenian historian Xenophon noted that at the end of the war, Athens would suffer the same fate as Melos at the hands of the Spartans.