Christianity began as a small offshoot of Judaism, concentrated on a small eastern province of the Roman Empire. Initially persecuted by Roman authorities, the early Christians still spread their message, in spite of near-certain death and martyrdom if caught. Over the centuries, the faith grew, and more people were converted to the once ostracized religious sect. Eventually, Christianity was adopted as the official religion of the Roman Empire and spread throughout Europe. Today it has over two billion adherents around the world.

Humble Beginnings & Internal Strife

Around the year 33 CE, a radical Jewish preacher named Jesus of Nazareth was executed by crucifixion in the Roman-controlled territory of Judea. Rather than dying, Christ’s message was carried on by his followers, who continued to preach. Centered around twelve of Jesus’ closest disciples, communities of believers began to spring up. For the most part, these groups were small and limited in scope. The new movement was still seen as an offshoot of Judaism, and converts still followed Jewish laws and cultural taboos, including dietary restrictions and the requirement that males be circumcised. Because of this, there was little reason to preach to Gentiles, and little incentive for non-Jews to join. Most of their preaching was done in areas that already had a large Jewish population.

This began to change over time, especially with the conversion of Saint Paul. Originally called Saul, Paul was an avid prosecutor of Christians, believing them to be heretics. According to tradition, Paul was on the road to Damascus when he saw a vision of Christ, who told him to stop persecuting his followers. Immediately, he changed his name to Paul and began preaching the message of Christ. Unlike the other apostles, who focused on their fellow Jews, Paul traveled widely around the Roman Empire, preaching to anyone who would listen. Most shocking of all, he did not require Gentiles to convert to Judaism or fulfill any of the other cultural requirements exclusive to them.

According to Church tradition, around this time, Saint Peter, one of Christ’s original disciples, had a vision in which he saw animals that were considered unclean according to Jewish law. He then heard God command him to eat, stating that these animals were no longer unclean. Shortly after, Peter baptized Cornelius, a Roman centurion, regarded as one of the first non-Jews to be baptized into the new faith.

These incidents changed Christianity from not a sect of Jewish belief into its own religion. With these barriers removed, the faith was now much more inclusive than exclusive, and anyone who professed belief was welcome, regardless of their background. This opening of the faith to a broader population did anger some in the burgeoning community, but they could not stop the march of “progress.”

The Persecuted Faith

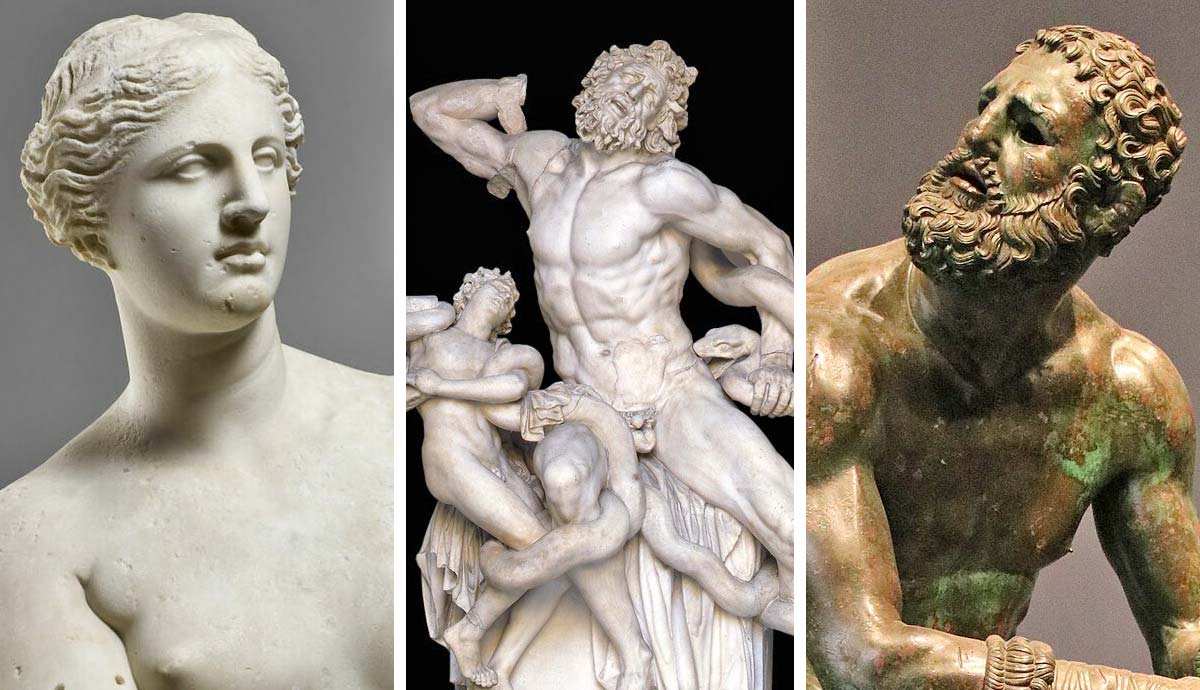

Generally, the Roman Empire was tolerant of a wide range of religious beliefs. More concerned with maintaining stability, they allowed any number of local beliefs to continue, so long as the citizens and subjects kept the peace and made sacrifices to the emperor. The Jews were given special consideration. Their strictly monotheistic belief system prevented them from making sacrifices to the emperor. As a compromise, the Romans allowed the Jews to make sacrifices to their God on behalf of the emperor. Since Judaism was an ancient religion, the Romans respected its longevity and (usually) didn’t press the issue much further.

In contrast, the new Christian faith not only did not make sacrifices to or on behalf of the emperor, but did not make sacrifices to any god at all, believing that Christ’s crucifixion was the final, ultimate sacrifice. They also adamantly refused to worship or acknowledge the emperor as a god. To compound this, the Romans mistook some Christian practices for social taboos. For example, the bread and wine used for communion are believed to become the body and blood of Christ. This was interpreted as human sacrifice and cannibalism. The habit of Christians referring to each other as brother and sister, and then marrying, also led to the mistaken belief that they were practicing incest, a major violation of Roman law and social norms. All of these factors together made Christians outcasts within Roman society. Still, the number of early Christians was small and generally overlooked.

This changed in the year 64 CE. After a fire devastated the city of Rome, the Emperor Nero needed a scapegoat, and these strange quasi-Jewish cultists were perfect for this. Christians around the empire, but especially those living in Rome, found themselves executed by crucifixion, being thrown to wild animals, or being burned alive. In spite of these trials, Christianity still continued to spread. After the initial wave of persecution died down, for the most part, members of the new religion were left alone. General imperial policy was to ignore them unless they made a nuisance of themselves; however, there were smaller, localized persecutions throughout the empire. There were empire-wide persecutions in the 3rd century under the emperor Decius and the last great persecution under Diocletian. By this point, Christianity was so well established that Diocletian would look out of his palace in Rome and see churches being openly built in the city. Christianity would be legalized in the empire with the Edict of Milan in 313 CE.

How Did It Happen?

So, how did a radical sect from the far fringes of the Roman Empire not only survive persecutions but eventually replace the pagan traditions to become the largest religion in the world? For the most part, it was a bottom-up effort. According to the belief, all were equal in God’s eyes, whether one was a slave or freedman, rich or poor, male or female, all were the same and had equal standing within the faith. This was directly at odds with the strictly hierarchical and patriarchal Roman society. This egalitarian belief appealed to the lowest members in the Roman world, slaves, the impoverished, and women, who embraced the new faith. Furthermore, there was no need for sacrifices, which were expensive and often not available to the lowest economic strata. A simple communal meal or even a silent prayer was enough. This made the new religion not only appealing, but also accessible. What mattered was faith and conviction, not monetary status. The Christian emphasis on charity and helping the needy also helped grow its reputation among the less fortunate.

Early Christians also engaged in aggressive missionary work and would preach the new faith to anyone who would listen. Many modern scholars also attribute the rapid spread of the ideology to so-called “sharing pyramids,” or early pyramid schemes. Generally, Christians would live and pray in small, tight-knit communities for mutual support. While they tried to keep a low profile to avoid unwanted attention from authorities, they would still try to attract new members. If each Christian helped convert two or three former non-believers, who then did the same, the numbers could grow very quickly.

While most Christians, like much of the population, tended to stay in one place, there were many who went on the road, literally. The Roman Empire was famous for its elaborate road network that connected all points of the Empire. These roads were built for the legions to move rapidly in the event of a crisis, but were also used by merchants and other travelers. Using these arteries, as well as shipping lanes, the word was able to spread. By the end of the 1st century, most Christian centers were in the Holy Land, as well as western and central Anatolia, Syria, Athens, and other coastal Greek settlements, and a small population in Rome itself. A century later, it had spread to much of Anatolia and the Levant, as well as large portions of Greece and the Balkans, Central Italy, Egypt, North Africa, Gaul, and Spain. With each generation, more and more of the Roman world was becoming Christianized.

Imperial Support

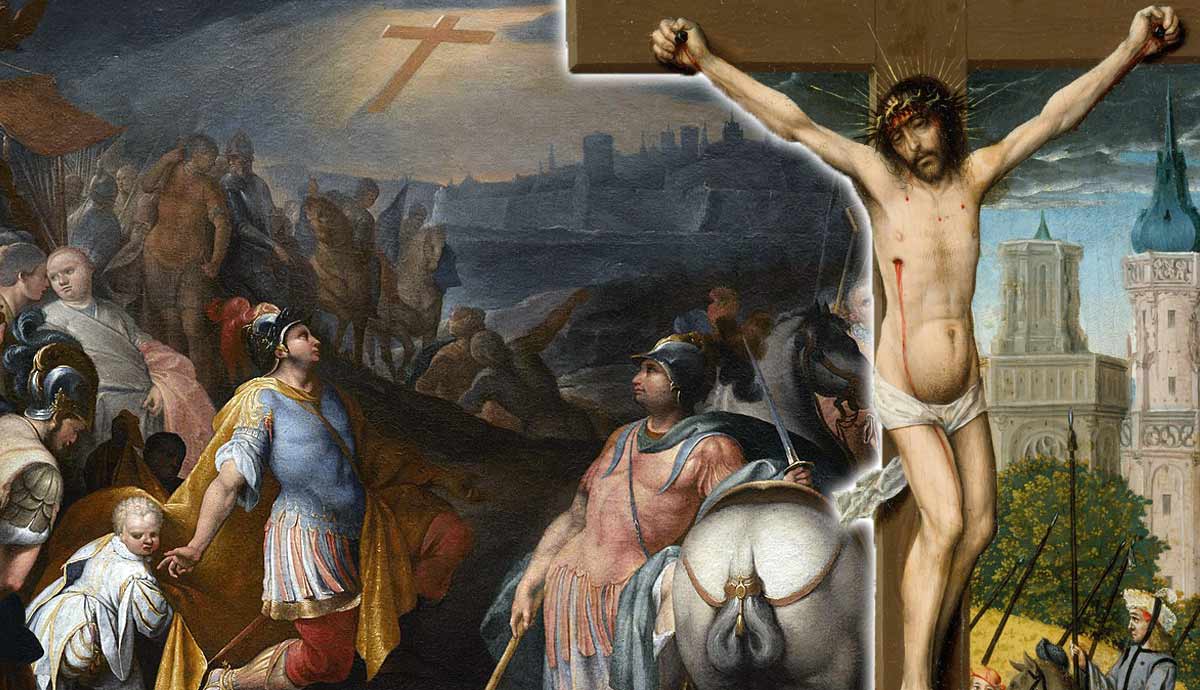

In the early 4th century, the Roman Emperor Diocletian initiated the Great Persecution, a widespread purge of Christianity throughout the Empire. Despite these efforts, the religion continued to flourish, and under Diocletian’s successor, Galerius, Christianity was granted official status as a protected belief system. Shortly after, the Empire was torn apart by civil war, in which Constantine embraced Christianity. According to Church tradition, before a battle, he saw a vision in the sky which gave the words “In hoc signet vicens,” or “by this sign, conquer.” Constantine ordered his soldiers to paint a Christian symbol on their shields. There is debate over the exact symbol, either a cross or a Chi Rho, the first two letters of Christ in Greek. In either event, the following battle at the Milvian Bridge saw Constantine victorious, making him ruler of the Roman Empire.

Historians doubt the validity of this tale, citing that no contemporary source mentions it. There is also doubt about how devout Constantine was and whether his views on Christianity were genuine or a cynical ploy to centralize power. Regardless, Constantine did favor Christianity heavily and issued the Edict of Milan, codifying Christianity as a protected religion. He was an avid patron of the monotheistic faith, sponsoring church constructions and even participating in the Council of Nicea, which resolved many of the specific controversies within the burgeoning Church.

Ironically, Constantine was not baptized until his deathbed, for reasons that are still debated. In spite of not being fully Christian, he continued to support the faith and turned away from earlier pagan beliefs. The Edict of Milan granted religious tolerance to the Roman Empire, but as his reign progressed, Constantine turned away from his earlier beliefs and began to suppress paganism. After Constantine, Rome was firmly Christianized, with the exception of a brief time under Julian the Apostate. From there, the religion would advance across Europe and the rest of the world.

Christianity Beyond Rome

One of the main tenets of Christianity is missionary work, and believers spread out into the world to gain converts. Although the conversion of the Roman Empire was arguably the most important geopolitical event in the history of the Christian religion, other nations and peoples also played a significant role. Armenia is credited as the first Christian kingdom. Their king Tiridates III converted in 301. Nearby Georgia became Christianized a short time later, probably around 319. There were also missions to India, Central Asia, Ethiopia, the Arabian Peninsula, and other places outside of the control of Rome.

As the Roman Empire began to crumble, it was overrun by Germanic tribes, many of whom were already Christian converts. For example, when Rome fell to the Goths in 410, the “barbarians” were already Christian and respected holy places while they pillaged the rest of the city. When Rome’s centralized government fell apart, the Catholic Church took on much of the administration necessary to keep society running. One of the Church’s missions during this time was to spread Christianity throughout the rest of western Europe. Clovis, the King of the Franks, converted in the early 6th century, marking a major milestone in the history of Christianity and European history, and laying the groundwork for the formation of the Carolingian Empire under Charlemagne.

Ireland was famously brought into the fold by the efforts of Saint Patrick in the 5th century, and missionaries from Rome and Ireland helped turn Anglo-Saxon England from paganism a century or so later. The Norse encountered Christianity and had a hostile relationship with the monotheistic faith, but gradually converted to the new faith over several centuries. In Eastern Europe, the Slavs in modern-day Ukraine and Russia became Christianized in the late 10th century thanks to contact with the Byzantine Empire and the efforts of Prince Vladimir the Great.

Conversion: The Easy Way, or the Hard Way

Conversion usually occurred on an individual level, with an increasing number of people in a population becoming Christian until a critical mass was reached, or when the monarch converted, which brought the rest of his subjects into the faith, whether willingly or not. Church traditions often depict the process as simple, with a declaration of the king being made, and that’s it, mass conversion in an afternoon. In reality, it was a gradual process that spanned several generations. Missionaries would often take a soft-handed approach, using the traditions of the local area to help spread their beliefs. For example, if a group of pagans were praying around a tree, they would consecrate the tree in the name of Christ and encourage the pagans to pray the same way, but to a new singular deity. In this way, they chipped away at resistance.

If necessary, however, force could be used. Charlemagne fought a brutal series of wars against the Saxons of Northern Germany. In these wars, he sought to subjugate the population and convert them to Christianity by any means necessary. At the Massacre at Verden in 782, Charlemagne captured and ordered the execution of around 4,500 Saxon heathens and the destruction of the Irminsul, a wooden pillar sacred to the Saxon pagans. After claiming Saxon territory, he ordered the death penalty for any unbaptized person, though he did relent from this uncompromising policy towards the end of his reign.

With this carrot and stick method, Christianity became the dominant faith in Europe by the end of the early Middle Ages. The last pagan holdouts were the Wends along the Baltic coast, who fought a series of wars with German kingdoms in the late 12th century. With this last pagan enclave gone, Christianity was the sole religion in Europe. Centuries later, during the Age of Exploration, Christian explorers brought their faith along with their search for gold and glory. As before, the use of both force and faith was applied, making Christianity the largest belief system on Earth, influencing the lives of billions around the world. This was a far cry from the obscure cult that developed on the fringes of the Roman Empire millennia ago.