Contrary to popular belief, the Neanderthals had language, hunting strategies, sophisticated tools, art, and jewelry. In many ways, they were not dissimilar from us. Having co-existed for thousands of years, there must be more to the story than humans simply wiping them out. For decades, academics have debated and questioned what caused their extinction, conceiving different explanations that interplayed with one another tens of thousands of years ago.

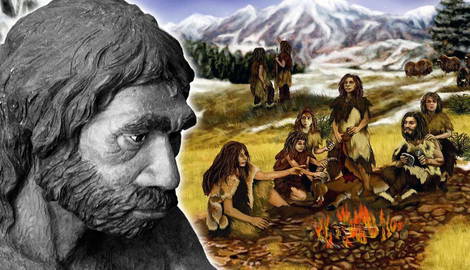

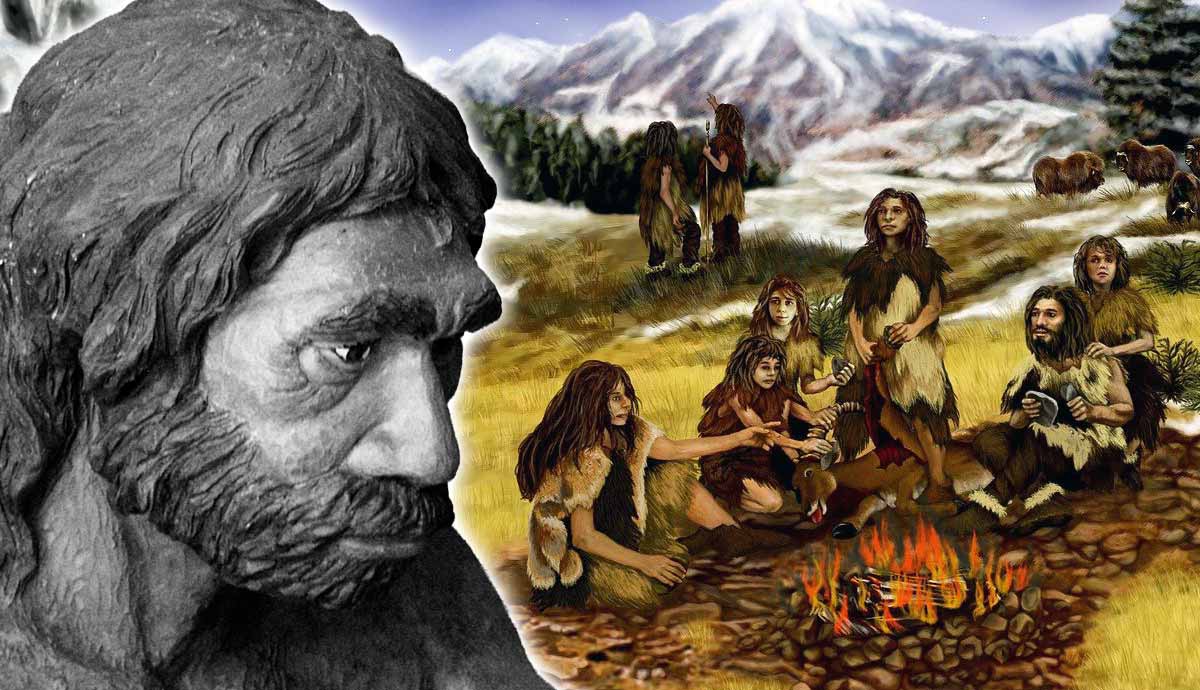

Who Were the Neanderthals?

Our own species, Homo sapiens, diverged from Homo neanderthalensis around 600,000 years ago before evolving separately in Africa and Eurasia, respectively. The first Neanderthal remains to be recognized were found in the Kleine Feldhofer Grotte of the Neander Valley in Germany, their namesake. Since then, we have come to know the species as our closest relatives, even discovering modern humans of non-African ancestry to have inherited 1-3% of their genome from Neanderthals. Remains have been found across Europe and Asia, from Portugal all the way to Siberia.

Neanderthals were stockier and shorter than humans, with larger brains, noses, and brow ridges. Physically, they were more robust and possessed short, powerful forearms that were adapted to the cold climate. They could bring down large herbivores using their strength, including reindeer, bison, and mammoths, to fulfill their predominantly carnivorous diet and high-calorie requirements. Researchers once believed Neanderthals to have been scavengers, incapable of the intelligence and organizational skills needed to hunt as our ancestors did. Today, research shows that groups of Neanderthals cooperated to ambush their prey using close-range thrusting spears before carefully selecting and butchering the carcasses.

Found in the famous Shanidar Cave, the discovery of an elderly Neanderthal, Shanidar 1, signified a trait that had not yet been associated with our “brutish” cousins: compassion. Despite suffering a blow to the head, an amputated arm, and profound hearing loss, the man survived to old age and had signs of healed fractures. Shanidar 1 was likely cared for by members of his social group, as he would have required protection from predators. Though also controversial, some researchers have attributed symbolic traits to Neanderthals, evidenced by burials, jewelry crafted from eagle talons, abstract cave paintings, and ritualistic rings of stalagmites.

When Humans Met Neanderthals

Anatomically modern humans began a significant dispersal out of Africa and into Eurasia approximately 60,000 years ago, where they met and lived alongside other hominins, Neanderthals and Denisovans. However, emerging genetic and archaeological evidence has revealed much earlier dispersals, leading up to the displacement of Neanderthals around 40,000 years ago. Researchers dated a fossilized cranium found in Apidimia Cave in southern Greece to at least 210,000 years ago, the earliest evidence of Homo sapiens in Eurasia.

DNA evidence has established that Neanderthals shared the same version of FOXP2 as humans, a gene involved in language development. It is possible that Neanderthals possessed spoken language, but distinctions between the languages of Homo sapiens and Neanderthals would far surpass any differences between modern ones. Considering the variations between our brains, languages, and behaviors, we can only imagine how these early interactions might have transpired.

Denisovans were more closely related to Neanderthals and interbred in Asia for hundreds of thousands of years. The remains of a young girl, “Denny,” revealed the extent of these interactions. Found to have had a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father, Denny was the first hybrid hominin researchers discovered. While scientists expected the male chromosomes of Neanderthals to appear more like those of Denisovans, genome sequencing revealed their Y chromosomes were closer genetically to modern humans. Neanderthal mitochondrial DNA, which is passed down by the mother, appeared more Denisovan 400,000 years ago. However, in later Neanderthals, the mitochondrial DNA resembled that of a modern human. A human mandible from Peştera cu Oase in Romania, dated around 40,000 years old, was found to have between 6-9% Neanderthal DNA, the highest of any modern human sequenced.

The Consequences of Interbreeding

Genome sequencing shows clear evidence that we interbred with Neanderthals before their extinction. How such interbreeding came about is up for debate. Did mating arise from convenience? Were these interactions violent or peaceful? While details of these early exchanges are largely lost to history, traces remain in the archaeological record. Analysis of a Neanderthal tooth found in El Sidrón contained the genetic signature of Methanobrevibacter oralis, a microorganism found in the mouths of modern humans today. These findings indicate an exchange of saliva, most likely through interbreeding. A variant of human papillomavirus (HPV) dominant in non-African populations, HPV16, was found to have spread to modern humans through sexual transmission from Neanderthal and Denisovan populations in Eurasia.

A reduction in Neanderthals’ breeding with one another, particularly considering their small and scattered groups, could have contributed to a decline in their numbers. If Neanderthals were consistently absorbed into human groups, as the archaeological record suggests, then fertile individuals were essentially removed from the Neanderthal gene pool. It is possible that interbreeding with humans was a contributor to the demise of the Neanderthals.

Small Networks, Big Problems

In addition to interbreeding, researchers have considered the consequences of inbreeding as a contributor to the extinction of Neanderthals. They had small, isolated social groups of around ten to 30 individuals. While anatomically modern humans were more likely to connect with other groups, Neanderthals were much more isolated. In fact, evidence from Siberia shows “mating networks” among early modern humans, helping them to avoid the negative effects of inbreeding and low genetic diversity. Comparatively, genomic analyses have revealed multiple isolated communities of late Neanderthals just before their extinction.

Researchers investigated the effects of inbreeding within a group of closely related Neanderthals found at El Sidrón in Spain, dated to around 49,000 years ago. From the 13 individuals, they observed 17 congenital anomalies, including defects of the rib, spine, and foot. At least four members of the group had congenital conditions. As inbreeding increases homozygosity, which increases the risk of expressing recessive traits, the overall fitness of the population would have been reduced.

As well as higher genetic diversity, bigger social groups offer advantages in battle. Neanderthals had larger builds and sophisticated spears, but modern humans had the advantage in numbers. Bigger group sizes meant humans could leave a battle and absorb the losses, while Neanderthal groups would likely suffer from any reduction in their group size. Networks with more people also have more opportunities to exchange information, supporting the development of complex technologies and the transmission of culture and knowledge from one generation to the next. With a drop in fertility rates, small populations, and low genetic diversity, there is a theory that Neanderthals could not compete with modern humans.

Coping With New Viral Diseases

When Homo sapiens began to migrate out of Africa and into Eurasia, they would have arrived with a range of infectious diseases that Neanderthals were not immune to. Anatomically modern humans co-evolved with pathogens in sub-tropical climates, and the survivors moved into Europe, where Neanderthals had not encountered such pathogens. Living in small groups, it is unlikely that diseases would have spread far among Neanderthal populations, but they would have spread more sporadically. While modern humans may have benefited from interbreeding with Neanderthals due to having a higher genetic resistance, Neanderthals had low genetic variability and a smaller effective population size. As a result, they would have had less immunity to introduced pathogens.

One explanation as to why Homo sapiens carried more infectious diseases than Neanderthals is due to zoonoses from animals such as African primate species. Many viral diseases are transmitted first from animals to humans, often developing in tropical or sub-tropical regions when people encounter wild or domesticated animals. Evidence supports that herpes simplex virus 2 was transmitted from chimpanzees to human ancestors around 1.6 million years ago in Africa and 52,000 years ago in Europe. Many of the infections that Neanderthals would have contracted from humans were chronic diseases that would have reduced their fitness and ability to perform everyday tasks required for survival.

Adapting to the Changing Climate

As the disappearance of the Neanderthals coincided with a period of climatic instability, researchers have considered the effect of the climate on their extinction. During the last glacial period, a series of abrupt, arid climate episodes occurred, known as Heinrich Stadials. These episodes were linked to discharging icebergs in the North Atlantic. In particular, scientists have linked Heinrich Stadial 4, a strong event that occurred around 39,000 years ago, to the extinction. These climatic changes likely reduced Neanderthal populations and their niche, and it is apparent that populations were already declining and becoming more isolated prior to Heinrich Stadial 4.

Scientists analyzed mineral deposits called speleothems from the Carpathian Mountains to reconstruct the climatic conditions at the time. Researchers have observed two prominent intervals with cold and arid conditions between 44,000 and 40,000 years ago. They hypothesize that Neanderthal populations dwindled during the initial cold period and were absorbed into human populations during the second.

Neanderthals developed adaptive strategies to survive multiple climatic shifts, including moving to areas with more moderate temperatures and managing their resources. However, as forest cover reduced, Neanderthals may have been less able to adapt to the grassy plains than Homo sapiens were. Reliance on large game could have meant Neanderthals were more heavily affected when animal populations declined. Comparatively, humans were eating plants, fish, and meat, making them more able to adapt to the changing environment.

So, Were Homo Sapiens the Superior Species?

Previously, there was a widespread belief that Neanderthals were inferior and that humans outcompeted them with better weapons, technological advancements, and intelligence. Early research pushed the ideology that Neanderthals were cruel, brutish, and foolish; a belief paleontologist Marcellin Boule heightened through his publication on the species. Boule examined an elderly, arthritic Neanderthal specimen with a hunched stature, equating these traits to be species-wide. Now, we know that Neanderthals were an intelligent, empathetic, and symbolic species that had sophisticated hunting techniques, language, art, and intentional burials. Much like intergroup conflict observed in chimpanzees, one would expect early modern human and Neanderthal groups to have fought for resources and territories. But, without conclusive evidence, it does not seem likely that warfare played a significant role in their extinction.

Although they are typically considered separate from the megafaunal extinctions, Neanderthals were one of over 100 large mammalian species to have gone extinct globally during the Late Pleistocene. Even before anatomically modern humans arrived, Neanderthals were diminishing in localized regions and suffered a decline in genetic variability. Discussions of their extinction have resulted in a divisive debate within the anthropological community. Many academics are interested in the significance for our own species, as they believe that contributing factors to the extinction of our sister species could reveal why humans were so successful. Regardless of the determining factor, Neanderthals still live on today in our DNA, leaving their legacy behind.