Conversation has fascinated intellectuals from all historical periods. We can follow the history of this interest. Beginning with some passages from the work of Marcus Tullius Cicero (106 – 43 B.C.E.), this narrative goes through the Renaissance and Enlightenment, etiquette manuals, and arrives at the recent discussions of the political dimension of human communication, such as Habermas’s theory of communication. However, the truth is that a single and complete art of conversation never existed.

What we do find in the writings of many intellectuals are sparse reflections that, when put together and compared, reveal many commonalities and contradictions. Through that comparison, we can contemplate many insightful perspectives about this seemingly unimportant act, one whose potential is often underestimated.

But before we begin, we need to clarify some concepts. We will start with a definition of conversation itself and its art. However obvious these may seem to the reader now, I think it’s worth taking a closer look at them.

“Neither the luxury of conversation, nor the possible benefit of conversation, is to be found under that rude administration of it which generally prevails. Without an art, without some simple system of rules, […] no act of man nor effort accomplishes its purposes in perfection.”

– Thomas de Quincey, Conversation

What Did Cicero (and Other Thinkers) Say About the Art of Conversation?

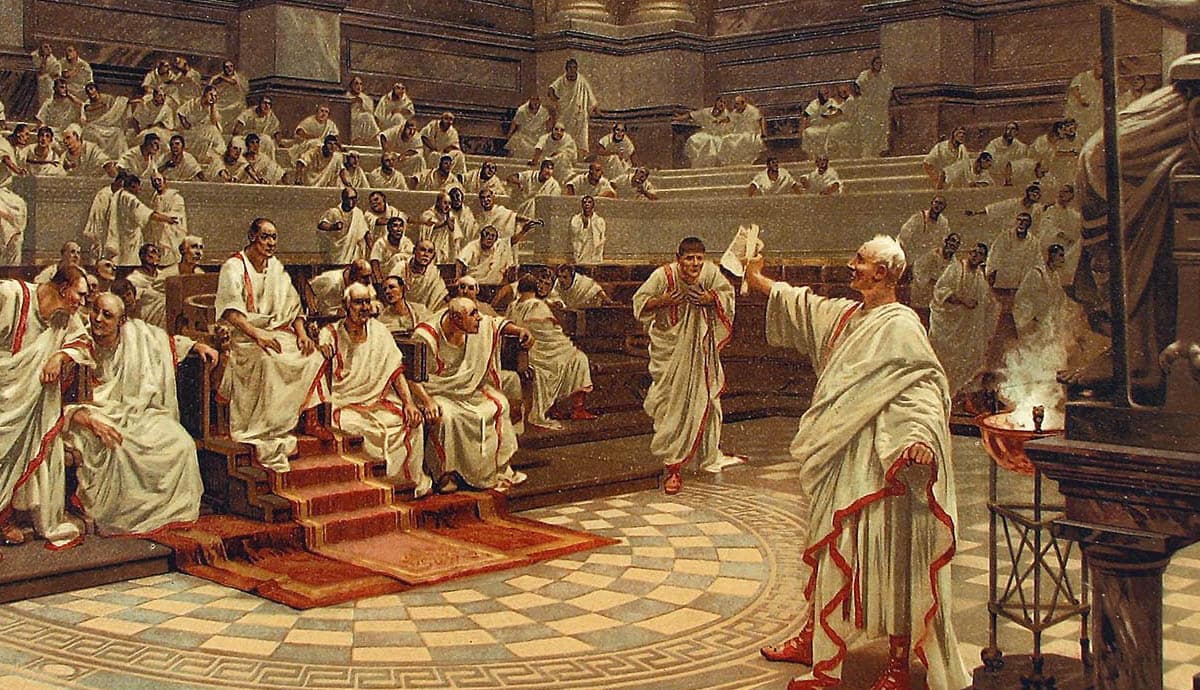

Two millennia ago, Cicero, in his On Duties, claimed that “Guidance about oratory is available, provided by the rhetoricians, but none about conversation, although I do not see why that could not also exist”. The lack of a specific guide did not need to mean that we cannot find any guidance, as Cicero himself stated: “However, such advice as there is about words and opinions will be relevant also to conversation”.

With the word “conversation”, according to Henry Fielding (1707 – 1754) in his An Essay On Conversation (1743), “…we intend by it that reciprocal interchange of ideas by which truth is examined, things are, in a manner, turned round and sifted, and all our knowledge communicated to each other”.

The conversation of intellectuals surely does fit this definition. For the most part, however, human conversation is much less pretentious. Conversation, to delineate a more precise definition than Fielding’s, is a form of communication that involves two or more interlocutors, who take turns in the roles of speaker and listener.

This definition, however, doesn’t say anything about what types of conversation there are. Here, I think that the classification proposed by Mortimer Adler in How to Speak, How to Listen (1997) can be useful. For Adler (and here he is echoing Cicero), there are two general types of conversation: the serious ones and those that are just for the sake of entertainment. The latter is also known as social conversation, which, as Adler says, is “enjoyable for its own sake, and not pursued for any ulterior purpose”.

According to Adler, there are three types of serious conversations: personal, intellectual, and practical (or deliberative). Each one has its own objective. Personal conversations are about emotions and personal problems and conflicts; intellectual conversations are about ideas, the truth or plausibility of some claim, and evidence and arguments; finally, practical conversations are about decisions that have to be made consensually by two persons or more.

These distinctions are important if we want to discuss the idea of the art of conversation. As it is implied in all of the texts I’m going to mention in this article, our objective is to isolate principles and rules that guide us towards excellence in conversation and teach us the patterns of action that best satisfy each of the objectives of the different types of conversation.

In what follows, we’ll take a look first at some principles for social conversation and, after that, I’ll expose some principles for intellectual conversations. In that way, I hope to offer a brief view of the history of the idea of an art of conversation and some of the main (and very basic) points of convergence in the literature about it.

The Rules for Social Conversation

It’s easy to underestimate the importance of an ordinary thing such as conversation. Concerning conversation in general, the Spanish philosopher Baltasar Gracián Y Morales (1601 – 1658) warned the reader of his The Art of Worldly Wisdom (1647) that “No human activity calls for so much discretion, for none is more common”.

Michel de Montaigne (1533 – 1592) also took conversation to be very important to human life. As he put in his essay On The Art of Conversation, a text that is part of his famous Essays (1580): “To my taste the most fruitful and most natural exercise of our minds is conversation. I find the practice of it the most delightful activity in our lives.”

The social conversation aims at pleasure. But the pleasures of social conversation vary in degrees, because it can be pleasurable in many different ways and because each pattern may be more or less adequately realized. Additionally, context also has its bearing. Usually, the intellectuals mentioned here tried to describe the patterns of action that lead to a good conversation in most everyday contexts.

But none of them suggests that possessing this art assures us of its intended results. There are always multiple people taking part in the conversation, and this means that having a good conversation is not entirely up to just one person. You can have the skills and that may compensate for what your partner lacks; but sometimes that just isn’t sufficient.

Concerning what is up to us, one absolutely important thing is the act of paying attention during conversations. Giovanni Della Casa (1503 – 1556) says, in his Galateo: The Rules of Polite Behavior (1558), that not paying attention is the safest way of assuring your interlocutor that you do not esteem his company. And, as Andre Morellet (1727 – 1819) wrote in On Conversation (1812):

“The obligation to listen is a social law that is incessantly broken. Inattention can be more or less impolite, and sometimes even insulting, but it is always a crime against society. However, it is very difficult not to become guilty of it with fools; but this is also one of the best reasons one can have for avoiding them because one avoids at the same time the occasion of hurting them.”

According to William Hazlitt’s (1778 – 1830) description of a good listener in his On the Conversation of Authors (1820), they had to be capable of listening to whatever was being told to them as if that was something that mattered to him in a personal way. In Hazlitt’s words: “He lends his ear to an observation as if you had brought him a piece of news, and enters into it with as much avidity and earnestness as if it interested himself personally”.

We say of someone that he is loquacious when he talks a lot. Gracián recommends that we take the caution of not talking too much. Instead, we should focus on being brief most of the time: “Brevity is pleasant and flattering, and it gets more done. It gains in courtesy what it loses in curtness. Good things, if brief: twice good. Badness, if short, isn’t so bad”.

Later, he adds: “To speak to yourself is madness; to listen to yourself in front of others, doubly mad”. Andre Morellet also condemns loquacity. This is the fifth conversational error that he addresses in his essay, which he calls despotism in conversation or the spirit of domination. In his own words:

“I call despotism in conversation at the disposal of certain men who are never at ease except in societies in which they dominate and in which they can assume the tone of a dictator. Such a man seeks neither to instruct himself nor to amuse himself, but only to give a high idea of himself. He intends to form, alone, the entire conversation.”

About the subject of conversation, that is, that of which we talk about, there is no general formula of adequacy. This doesn’t mean that there is no relevant rule about this matter. For example, Della Casa suggests that we should avoid themes of human suffering, especially at the table and at parties.

Philip Stanhope (1694 – 1773), 4h Earl of Chesterfield, in one of his famous Letters to his son (1774) recommends more than once to him that he should talk about what is interesting to others, not something that he finds amusing.

As Lord Chesterfield wrote: “Of all things, banish the egotism out of your conversation, and never think of entertaining people with your own personal concerns or private affairs; though they are interesting to you they are tedious and impertinent to everybody else”. Swift agreed:

“Of such mighty importance every man is to himself, and ready to think he is so to others; without once making this easy and obvious reflection, that his affairs can have no more weight with other men, than theirs have with him; and how little that is, he is sensible enough.”

In fact, the second conversational mistake that Swift addresses in his essay is that of those who always try to talk about themselves. In his own words: “Some, without any ceremony, will run over the history of their lives; […] will enumerate the hardships and injustice they have suffered in court, in parliament, in love, or in law”.

An especially acute way of harming one’s reputation through egotism in conversation is the habit of trying to elevate the opinions about oneself covertly. Jean de la Bruyère (1645 – 1696), author of The Characters (1688), exposes the hypocrites that wish to be seen as honest, as well as flatterers and arrogants that try something similar. About honesty, he writes:

“He who continually affirms he is a man of honor and honesty as well, that he wrongs no man but wishes the harm he has done to others to fall on himself, and raps out an oath to be believed, does not even know how to imitate an honest man. An honest man, with all his modesty, cannot prevent people from saying of him what a dishonest man says of himself.”

Finally, it is wise to be careful with humor. Baldassare Castiglione (1478 – 1529) in The Book of the Courtier (1528) advises caution with jokes: “But at all times attention should be paid to the disposition of those who are listening, for jokes can often make those who are suffering suffer still more, and there are some illnesses that only grow worse the more they are treated”. Keep in mind that this is advice for ordinary social conversations, not for stand up comedians.

Fielding also thought that we need to be careful with humor. There are those, however, that shouldn’t try to tell jokes or be funny, because it just isn’t a skill they have. That’s why Fielding says that humor “is a weapon from which many persons will do wisely in totally abstaining”.

What Are Intellectual Conversations?

In general, a good intellectual conversation (or intellectual debate) happens when there is mutual comprehension, when every proposition and argument put forward is discussed in light of the adequate criteria of epistemic evaluation. The best outcome is the gaining of important knowledge about the issue, not necessarily the formation of a consensus.

A derailed debate may be called a dispute. William Cowper (1731 – 1800), in his poem Conversation, states: “Preserve me from the thing I dread and hate, / A duel in the form of a debate”. We all know too well how stressful a debate can be.

Centuries before the theory of controversies of Marcelo Dascal (1940 – 2019), Morellet developed a simple criterion to distinguish between disputes and debates: “I call debate the allegation of reasons and arguments which support two opposing opinions, while it confines itself to combating the opinion itself, quite apart from the person, and I see it degenerate into dispute the moment any offensive allusion is introduced into it”.

But it is Montaigne who best exemplifies the true spirit of debate. Again, in his essay On the Art of Conversation: “When I am contradicted it arouses my attention not my wrath. I move towards the man who contradicts me: he is instructing me. The cause of truth ought to be common to us both”.

There are many things to say about intellectual conversations. In short, to be successful, they need to be performed according to certain rules. Most of the time, we ignore this in our daily discussions. But for a long time, philosophers have been stressing the importance of the method of human communication, in explaining why democratic debate needs structure to be fruitful.

In that regard, it is worth mentioning the work of German philosopher Jürgen Habermas (1929 – ). Although he wasn’t theorizing about conversation, his theory of communication, and specifically his ethics of discourse, have many points of contact with previous (and much simpler) reflections on the importance of structure in intellectual debates.

Habermas emphasized the three levels of rules that should be observed for a good debate to happen. He proposed we should share the same set of linguistic and logical rules, but also be sincere and maintain integrity; communication should also be guided by rules against coercion and inequality.

Habermas’ theory of communication offers various insights into the current collapse of communication between groups with different opinions. In that regard, his work is quite close to the subject of this article

From Cicero to Habermas: The Importance of Conversation for a Good Life

The importance of conversation is something that we tend to forget. Be it social or serious, conversation can provide us with many good things in life: from reinforcing the bonds with people who matter to obtaining important knowledge (don’t forget that Socrates did philosophy through dialogue), this ordinary act is full of potential, both for the good and the bad.

Much has been said about the consequences of the different styles of communication (think about the current discussions on nonviolent communication, for example) on our personal lives. And much has been said of the present state of public discussion. However, the idea of the art of conversation still seems to many a waste of time. Of course, in our world full of gurus and self-help books of questionable quality, this concern has some merit. But that’s not the whole picture.

As I tried to show, many of the greatest minds in history thought that this subject deserved more attention. We also live in a time when many sciences have grasped the knowledge about the workings of patterns in communication. Considering all that, for my part, I’m with Cicero: I don’t see why we shouldn’t have a clear and precise art of conversation. I think its history can inspire us to search for a more scientific one in the future.