Chinoiserie is characterized by the widespread use of Chinese motifs such as pagodas and dragons and an abundance of natural elements in European artistic and decorative styles. While this synergy arose from increased trading and diplomatic relations with China, Chinoiserie has been noted as an idealized European interpretation of Chinese culture. It was a glimpse into the Orient based on how diplomats, missionaries, and traders viewed China. Let’s delve into the unique development of Chinoiserie and explore how it became one of the most prominent artistic styles of its time.

Introduction to Chinoiserie

From the French word chinois, the term Chinoiserie means Chinese or relating or belonging to China. An entirely European creation, Chinoiserie reflected the sensibilities of a time when travel was reserved for a select few in society. In the 17th century, travelogues, artworks, and ceramics were the few sources of information for the layperson to understand a faraway, foreign culture. As such, Europeans did not have a complete picture of what constituted authentic Chinese culture. Often, they pieced together Chinese, Indian, and Japanese elements, forming a tapestry of orient culture. Generations of designers depended on second-hand information from publications as key references. Among these were the 1665 travelogue remarkable voyages & travells into ye best provinces of ye West and East Indies by Dutch traveler John Nieuhoff and the 1754 trade catalog The Gentleman and Cabinet-maker’s Director by English designer Thomas Chippendale.

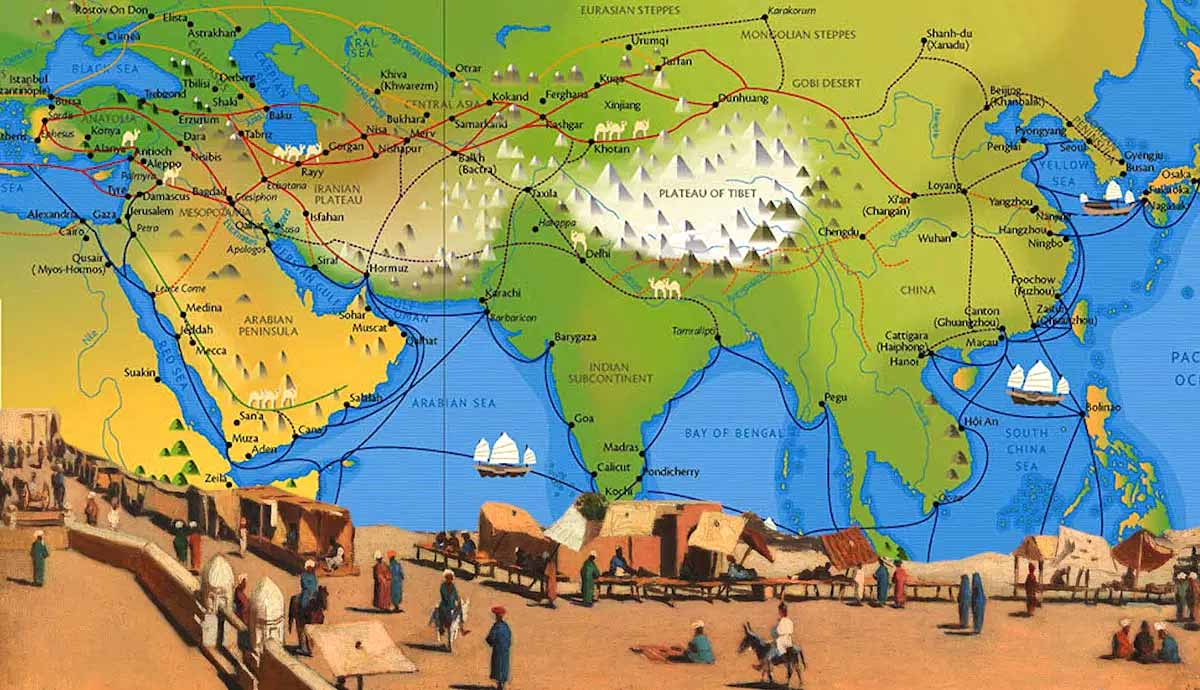

The Role of Trade in Popularising Chinoiserie

Historically, China had established robust trading relations with Europe owing to a network of complex and ever-changing trade routes known as the Silk Road. From the early 16th century, Sino-European trade further expanded, and an influx of Chinese goods such as silk, porcelain, and lacquerware entered Europe. This allowed the Europeans to imitate Chinese designs and magnify “oriental motifs” such as exotic flora and fauna, eastern-looking infrastructures, and mythical beasts. These Chinoiserie creations went hand in hand with the popular Rococo designs of the time, as both styles featured lavish decorative elements.

Rococo: Chinoiserie’s Equally Exuberant European Cousin

From the French word rocaille, which means rock or broken shell, Rococo is best characterized by its liberal use of exuberant decoration, asymmetry, and curves. A reaction to the severity of the Baroque style, Rococo looked to nature and featured leisurely and pleasurable pursuits in a pastoral setting. Given its subject matter, Rococo was strongly associated with aristocracy, emphasizing its frivolity and privilege. Rococo first took root in France and later gained prominence across Europe in northern Italy, Austria, southern Germany, and Russia. Its profound influence has since remained etched in the arts, music, theater, and literature to this day.

Rococo came into vogue in the early 18th century, around the same time Chinoiserie became popular. This meant that Rococo artists had Chinoiserie elements at their disposal to incorporate into their works, creating a unique fusion of Chinese and Rococo aesthetics. French painter François Boucher was best known for promoting this synergized art style. Boucher worked as a head painter in the royal court of Louis XV of France and was favored by his mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Despite having never traveled to China, Boucher’s works, such as Festin de l’empereur de Chine (1742) and Chinoiserie (1750), even with inaccuracies, gained celebrity in his lifetime and beyond.

Motifs Associated With Chinoiserie

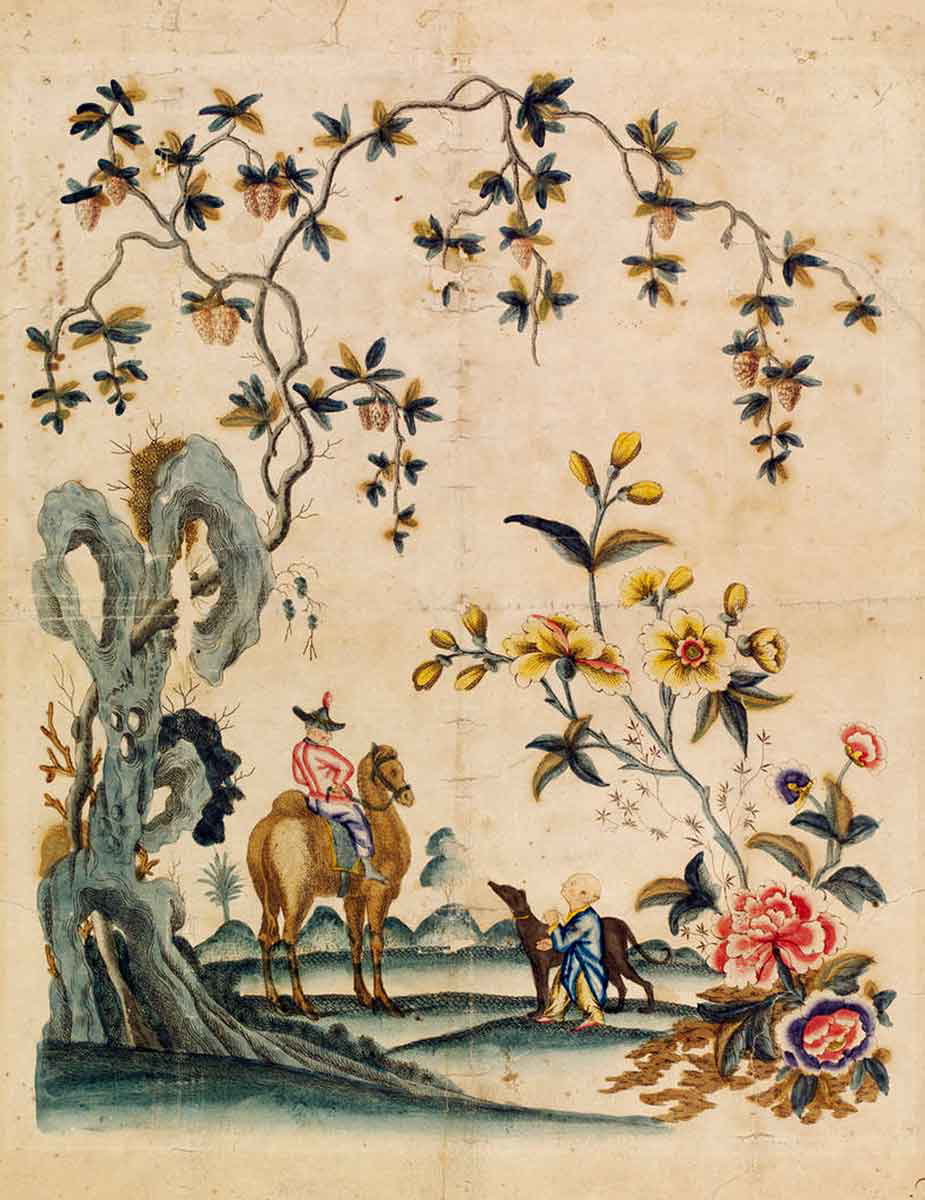

Among the intricate elements of Chinoiserie were dragons, phoenixes, foo dogs, pagodas, and an abundance of flowers. Representing all things auspicious, dragons and phoenixes have long held a symbolic place in Chinese culture. They were synonymous with imperial power, appearing on the robes, furnishings, and thrones of Chinese royalty. Thought to have mythical powers to protect official buildings, foo dogs—also called Chinese guardian lions—were also a popular Chinoiserie motif. Towering Chinese pagodas, most associated with Buddhism, too, were often depicted in paintings and wallpapers alongside peonies, azaleas, and chrysanthemums.

A Royal Obsession With Chinoiserie

European aristocracy and members of high society saw Chinoiserie elements as a symbol of status and wealth. A testament to its popularity, Chinoiserie inspired the extravagant décor for many royal properties. In 1670, Louis XIV of France ordered the construction of what was to become Europe’s first Chinoiserie building—the Trianon de Porcelaine, located within the Palace of Versailles. Decked out in the quintessentially Chinese blue and white ceramic tiles, the building was inspired by the Ming-era Porcelain Tower of Nanjing in China.

In 1748, Louis César de La Baume Le Blanc, a French nobleman, added a Chinese Salon in his Château de Champs-sur-Marne in France. The décor of the Chinese Salon featured large panels of oriental floral and fauna. It also displayed imagery of men with Asian features riding horses, playing pole archery, and even hunting ostriches (which isn’t exactly a Chinese practice).

English royals were equally enamored by Chinoiserie. King George IV of England incorporated elements of it within the rooms in Buckingham Palace, as well as in the Royal Pavilion at Brighton, his seaside residence. The Frogmore House, located within Queen Charlotte’s Windsor Castle, was another fine example of Chinoiserie. Three of its rooms—the Japan Room, the Green Closet, and the Black Japan Room—showcased numerous furnishings imported from the Far East. It was said that some of the finest gifts presented to King George III by Emperor Qianlong in 1793 were also housed here, including imperial-grade porcelain, jade, red lacquer caskets, and silk.

Collecting Chinoiserie: A Predominantly Feminine Pursuit?

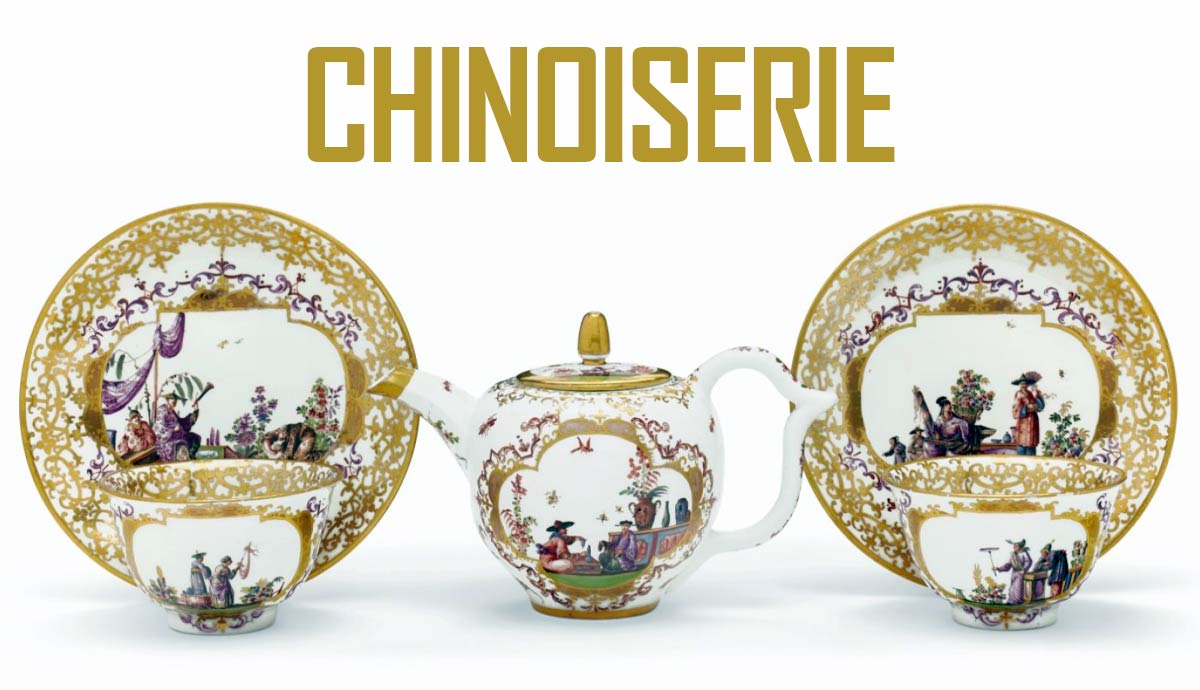

European elite, especially women, were fascinated by the elegance and intricacies of Chinoiserie and imported Chinese goods. Henrietta Howard, the Countess of Suffolk, and Catherine II of Russia were both known for their vast collections of Chinese porcelain and artifacts. From porcelains and silks to lacquerware and wallpapers, these exquisite markers of luxury and class were amassed as décor for dressing rooms. Here in these spaces, women hosted their guests and showed off their luxury Chinoiserie collections. As they fuelled the Chinoiserie craze, it, too, contributed to the growing stereotype of women being frivolous buyers easily swayed by trends and the exotic.

Coincidentally, this came at a time when tea-drinking evolved to become a common pastime, particularly in Britain. Between 1700 and 1704, more than 200,000 pounds of tea arrived on British shores via large ships called East Indiamen. English women, whether of upper or middle classes, indulged in adorning their drawing rooms with imported Chinese tea ware and European-made copies. In 1734 alone, Britain imported more than one million pieces of Chinese porcelain. Greater demand for porcelain tableware quickly spurred local imitations. The Chelsea Porcelain Factory in London, established in 1745, successfully produced luxury soft-paste porcelains suited for the taste of the well-heeled.

Criticism and Dwindling Popularity of Chinoiserie

Despite its popularity, Chinoiserie was criticized for being a vulgar and superficial style that was lacking in logic and reason. Robert Morris, one of the most influential 18th-century British writers, opined that Chinoiserie consisted of “meer [sic] whim and chimera, without rule or order,” adding that “it requires no fertility of genius to put in execution.” Outlandish and fraught with inaccuracies, some saw Chinoiserie as a mockery of genuine Chinese culture. A few even went as far as to make a connection between women and their mindless collection of Chinese and Chinoiserie items. British essayist and poet Joseph Addison was one such vocal critic.

“But in the last place, Chinaware is of no use. Who would not laugh to see a smith’s shop furnished with anvils and hammers of China? The furniture of a lady’s favourite room is altogether as absurd: you see jars of a prodigious capacity that are to hold nothing.” – Joseph Addison, The Lover, 17 March 1714

By the 19th century, British imperial ambitions had extended far into Asia, with the colonization of India and the establishment of trading outposts across Southeast Asia. A key factor contributing to the waning interest in Chinoiserie was the First Opium War in 1839 between Britain and China. It was a conflict sparked by the Chinese government’s ban on the illegal opium trade, which was Britain’s most lucrative commodity trade at the time. As several naval battles ensued, the conflict eventually ended in China’s defeat and the signing of the Treaty of Nanking, which the Chinese regarded as the first of many unequal treaties. Economically, political tensions dealt a significant blow to international trade, restricting Chinese imports, which had been the key driver of the Chinoiserie craze in Europe.

20th Century Revival of Chinoiserie

Despite a lull in the 19th century, Chinoiserie enjoyed a popular resurgence in the early 20th century. The Jazz Age in America precipitated the liberation in women’s fashion. Chinese coat designs, characterized by wide sleeves and armholes, had a profound influence on Western fashion, which was undergoing an overhaul. Instead of a suffocating corset, the women of the 1920s opted for the emancipating loose tubular dresses.

The Chinese Room also made a comeback as oriental décor became a popular interior choice. Lush Chinese carpets, red lacquered furniture, Buddha ornaments, scarlet upholstery, and wallpapers featuring generic Chinoiserie motifs adorned homes. While the splendor might have created the illusion of 18th-century grandeur, the reality was far from it. Given the ongoing political upheavals, the lavish use of Chinoiserie was perceived as a delusional nostalgia for simpler, romanticized times, unburdened by warfare and violence.

A Critical Look at the Legacy of Chinoiserie

The history of Chinoiserie has been complicated by political turmoil, and often, it hovered precariously between cultural appreciation and appropriation. At its core, Chinoiserie manifested as an idealization of the East, largely a figment of the Westerners’ imagination of the exotic Orient. The dangers of homogenizing diverse cultures, as well as reducing civilizations of over 5,000 years to mere superficial motifs, remain two compelling arguments against Chinoiserie. On the flip side, some have given credit to how Chinoiserie “initiated an artistic dialogue between Europe and the East, resulting in a creative fusion that combined elements from both cultures.” Questionable as its origins might have been, Chinoiserie has left an indelible mark on decorative arts, architecture, literature, theatre, and music. With the benefit of increased cultural understanding and caution against appropriation, Chinoiserie continues to influence contemporary design and inspire cultural cross-pollination today.