Through expanded trade with Qing China from the 16th century, Europe developed a fascination with Chinese culture. This birthed Chinoiserie as a decorative style in the late 17th century, referring to the use of Chinese motifs such as pagodas, dragons, flora, and fauna in Western art. Rococo, with its roots in 18th-century France, is best known for emphasizing ornamentation and elegance. With a shared focus on exuberant decorative elements, Chinoiserie and Rococo have several overlaps. How did these styles develop, and what are the key differences between them?

1. Chinoiserie Predates Rococo

Chinoiserie emerged in the late 17th and early 18th centuries owing to heightened trade and cultural exchanges with China. Derived from the French word chinois, Chinoiserie means “Chinese” or “relating or belonging to China.” An entirely European creation, Chinoiserie was created by Europeans for Europeans, based on how they imagined China or the Far East to be. However, while Chinese-looking motifs featured heavily in European arts, fashion, textiles, ceramics, and décor, they sometimes risked looking stereotypical and even artificial. Nonetheless, during a time when international travel was rare, Europeans indulged in the craze of collecting Chinoiserie—a pastime regarded as a status symbol. European elite, especially women, were known to be avid collectors of Chinoiserie and imported Chinese goods, which adorned tea rooms and dressing rooms.

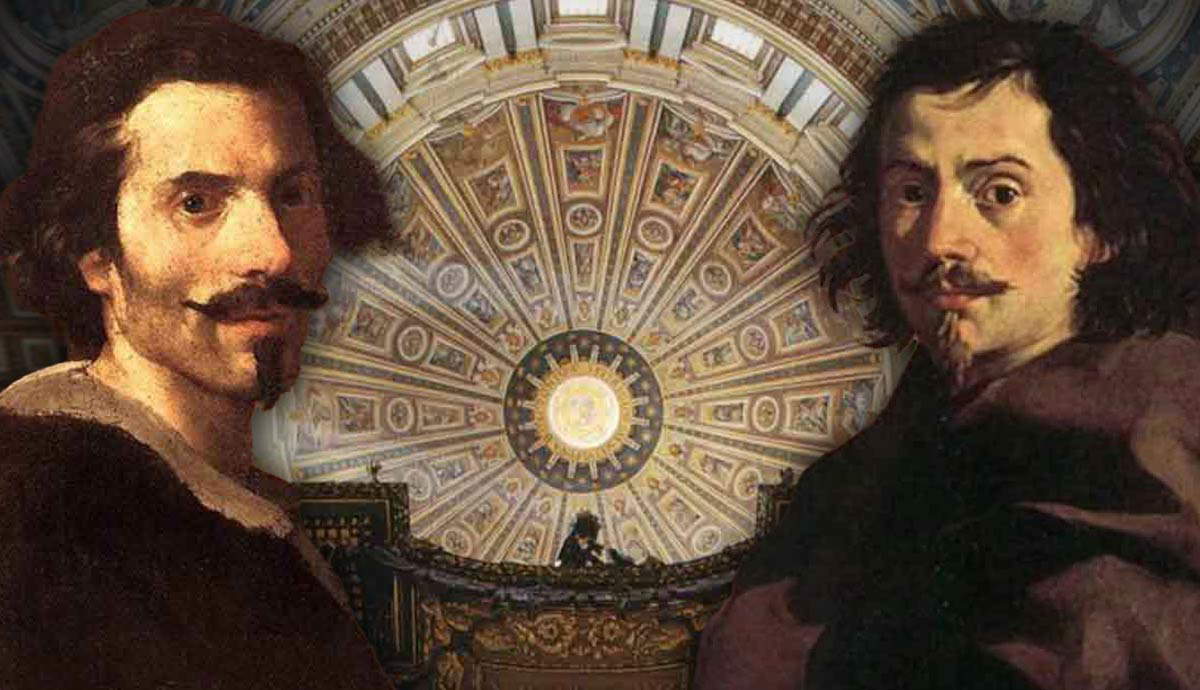

2. Rococo Came Next

In the early 18th century, somewhere around the 1720s, Rococo came into vogue, originating from France as a reaction to the severity of the Baroque style. Derived from the French word rocaille, which means “rock” or “broken shell,” Rococo features exuberant decoration, asymmetry, and curves. Sometimes perceived as frivolous, it was a style favored by aristocrats. It emphasized natural elements and leisurely pursuits in pastoral, idyllic settings. The style has also been described as theatrical, as Rococo interiors tend to focus on elaborate moldings and gilded accents. Proponents of the Classical styles did not appreciate Rococo, which was seen as superficial, degenerate, and illogical.

3. Chinoiserie Was About an Idealized China

At its core, Chinoiserie was all about the Europeans’ idealized view of China and what they thought China was. What they assumed to be Chinese culture was, in reality, far from the truth. Without the ease of travel and access to knowledge, European designers relied on their imagination and the limited information derived from travelogues and hearsay. This formed a warped, superficial view of China and the Far East, which was often a mish-mash of random Chinese, Indian, and even Japanese elements.

Europeans did not often make the conscious distinction between these individual cultures and centuries-old civilizations. In fact, it was a time when few could pinpoint where these countries were on the world map. Inadvertently, when viewed through the critical lenses of modernity, it is challenging to disassociate Chinoiserie from the broader, more controversial topics of Orientalism and Western imperialism.

4. Rococo Promoted Elegance and Sophisticated Pleasures

On the opposite end of the spectrum lies Rococo, which epitomizes the pleasurable, sometimes removed, lifestyle of 18th-century European elites. Apart from emphasizing exuberant decoration, asymmetry, and curves, a key characteristic of Rococo is its often idealized and idyllic pastoral settings. Rococo works espoused a romanticized notion of rural life, often depicting unrealistic scenes such as elegantly dressed aristocrats seemingly involved in farm work. François Boucher’s work The Love Letter (above) shows two well-dressed women lounging in the lush countryside, enjoying each other’s companionship. They were believed to be shepherdesses, judging from the flock of sheep and the dog nearby. However, as with most Rococo pieces of the time, work was of the least concern as the ladies preferred to occupy themselves with collecting flowers and sending letters.

5. Rococo Motifs Included Shells, Flowers, and All Things Pastoral

Exuding a sense of playfulness and delicacy, Rococo featured motifs such as shells, flowers, ribbons, and vines, usually in a rustic countryside setting. Rural lifestyles were heavily romanticized and completely far from what reality entailed for the masses. In Rococo works, its gardens appeared manicured and ornate, and its shepherds and shepherdesses looked too poised to be working on peasant farms. Apart from the aristocracy, another common subject found in Rococo works were the putti or cherubs, who often appeared as chubby, naked babies, sometimes with wings. They represented innocence, purity, love, and playfulness—all quintessential Rococo elements. L’Amour Moissonneur by François Boucher depicts a group of putti or cherubs in a wheat field as an allegory of summer.

6. Chinoiserie Motifs Included Dragons, Pagodas, and Chinese-Inspired Elements

Common objects found in Chinoiserie included fantastical landscapes, bizarre-looking pavilions, fanciful Chinese pagodas, and a bunch of mythical creatures such as dragons and phoenixes. The abundance of floral motifs, including peonies, azaleas, and chrysanthemums, was also a popular addition. Sometimes, Chinoiserie pieces featured what appeared to be Chinese or Asian-looking figures, which somehow looked rather bizarre or uncanny compared to works originating from China. This, again, goes back to the lack of travel opportunities and access to knowledge. As such, European designers often took traditional Asian or Asian-like symbols and modified the scale and proportion in a bid to accommodate Western tastes and aesthetics.

7. Rococo Declined in the Late 18th Century

Largely depicting the lifestyles of the rich and privileged, Rococo struggled to appeal to the masses. Condemned for its decadence and superficiality, the movement gradually declined towards the end of the century with the emergence of Neoclassicism. Just as Rococo had been a reaction to the severity of Baroque, Neoclassicism was a stark contrast to the excesses and frivolity of Rococo. Depicting subjects associated with Ancient Rome and Ancient Greece, Neoclassicism promoted the principles of simplicity, symmetry, and order. This was in tandem with the Age of Enlightenment, which emphasized morality, reason, and rationality. From the 18th century through to the 21st century, Neoclassical styles have continued to be influential, especially in architecture.

8. Interest in Chinoiserie Waned in the 19th Century

Like its Rococo cousin, Chinoiserie was criticized for lacking in logic and reason. Its association with royalty, such as King Louis XV, made it synonymous with the decadence that was increasingly frowned upon. The absurd inaccuracies in European imitations also angered those who saw them as mocking authentic Chinese culture. More significantly, Chinoiserie fell into decline with the outbreak of the First Opium War in 1839. Fought between Britain and China, the conflict began when the Qing government banned the illegal opium trade, which was the most profitable commodity trade for the British Empire in the 19th century. Heightened political tensions between the two countries had a devastating impact on international trade. This led to restricting Chinese imports, which had long been the key driver of the Chinoiserie craze in Europe.

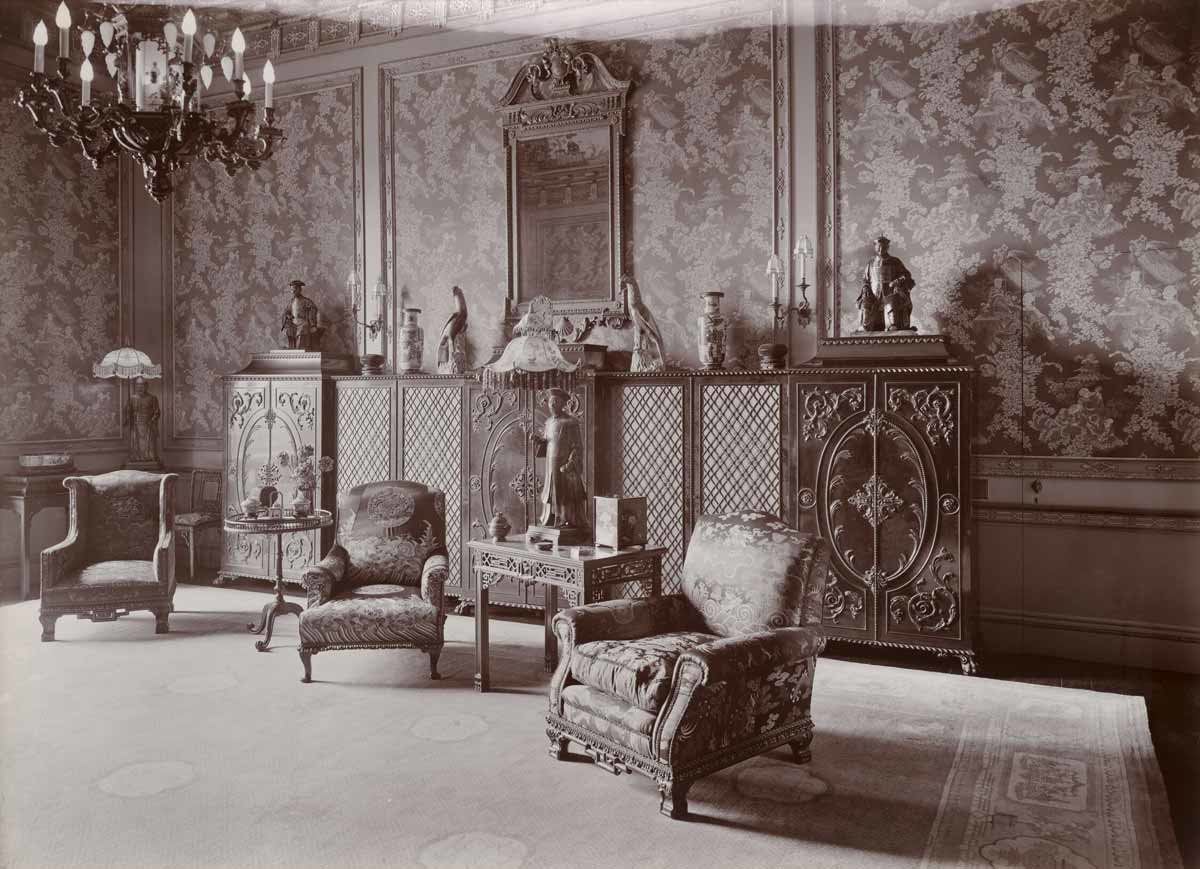

9. Both Rococo and Chinoiserie Enjoyed a Revival

Less than a century after its decline, Rococo reinvented itself in the 1820s, this time as a movement called Rococo Revival. It sought to revive the 18th-century grandeur and opulence of Rococo but with a modern twist. While semblances of the Rococo Revival style were evident in paintings and decorative objects, the revival focused primarily on furniture and interior design. With the availability of new technology, such as plywood lamination, which used steam and pressure, curves in furniture were achieved more easily. Mahogany and rosewood were also quintessential Rococo Revival elements, accentuating the lavishness that had once taken Europe by storm. However, unlike its predecessor, Rococo Revival was not limited to Europe as its popularity spread and soared in the United States as well between the 1840s and 1860s.

By the start of the 20th century, Chinoiserie was in vogue again. This coincided with the rising influence of Chinese coat designs, characterized by wide sleeves and armholes, in Western fashion trends. Women began ditching the restricting corsets for the emancipating loose tubular dresses popular during the Roaring Twenties. It was a time of increased consciousness with the accelerated momentum of the women’s rights movements. Oriental décor featuring Chinese carpets, red lacquered furniture, Buddha ornaments, scarlet upholstery, and wallpapers also became sought-after interior design choices. Though the 20th century hailed the comeback of Chinoiserie, some have argued that the resurgence was mere nostalgia for simpler, romanticized times. Others believed it was a coping mechanism for the upheavals and political tensions plaguing the Western world then.