The Church of the Holy Sepulcher is one of the most important sites in Christianity. According to Christian belief, it encompasses the place where Christ was crucified, buried, and resurrected. As such an important location, the church built on the location has become a focal point for Christian belief and a holy relic of the highest magnitude. Over the centuries, especially during the crusades, countless pilgrims visited the location, and many have risked their lives to defend it. This is the history of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

Humble Beginnings

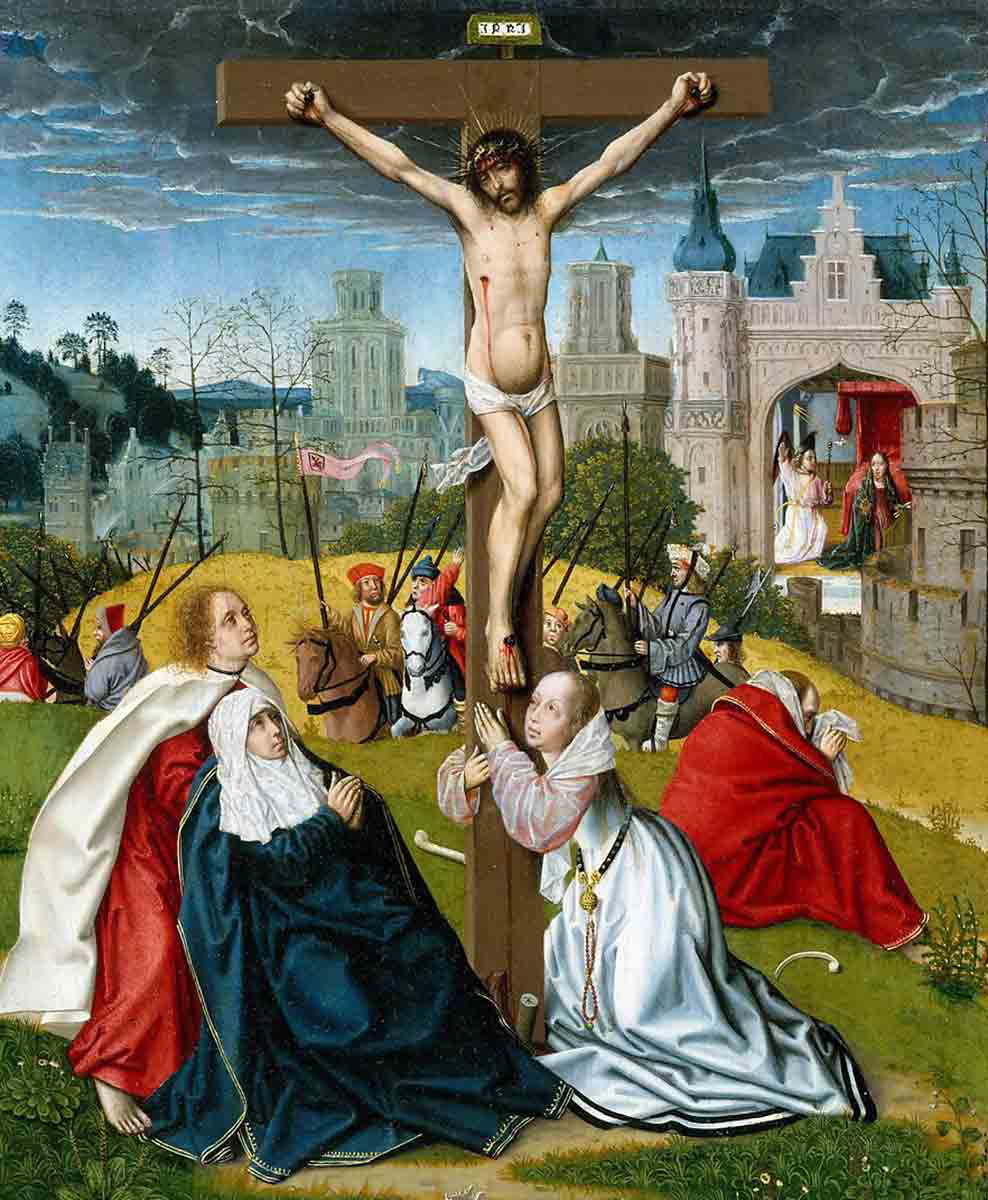

Around the year 33 CE, revolutionary Jewish preacher Jesus of Nazareth was executed by crucifixion. According to the Bible, this took place at a location known as Golgotha, or the Place of the Skull, which was believed to be a disused stone quarry just outside the walls of the city of Jerusalem. His body was then placed in a nearby tomb hewn out of rock, where he was said to have resurrected after three days. While Christ’s followers spread the word of his teachings, the Roman Empire, which ruled the region, had other concerns for Jerusalem.

In the year 70 CE, the Romans captured Jerusalem in response to a Jewish revolt, bringing utter destruction to the city. Decades later, in 130 CE, the Emperor Hadrian ordered the construction of a pagan temple on Golgotha. This temple, dedicated to either Jupiter or Venus (the sources vary), stood on the spot for several centuries. At the same time, Christians were slowly gaining influence throughout the empire. In 313 CE, Emperor Constantine issued the Edict of Milan, ending the persecution of Christians. In 326 CE, the pagan temple was replaced by a church on the site where it was believed Christ was crucified and buried, which was consecrated in 335 CE.

In 614, the Sassanids invaded Jerusalem and destroyed the Church, which was subsequently restored by the Byzantine emperor in 630. When Jerusalem fell to Islamic forces in 637-638, the Sepulcher was respected and undamaged by the conquering forces. Over the next few centuries, it was damaged by earthquakes and several fires, but was rebuilt each time. The worst damage occurred in 1009 when the Sepulcher was destroyed by the caliph of the Fatimid Caliphate. In 1048, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX restored the church, despite Jerusalem not being part of the Byzantine Empire. The style of the building was changed, and it was rebuilt as a smaller structure with a number of separate chapels instead of one large structure. Although Jerusalem was under Islamic control, the actual Sepulcher was overseen by Christians and remained a major pilgrimage site for devout Christians.

The Crusades

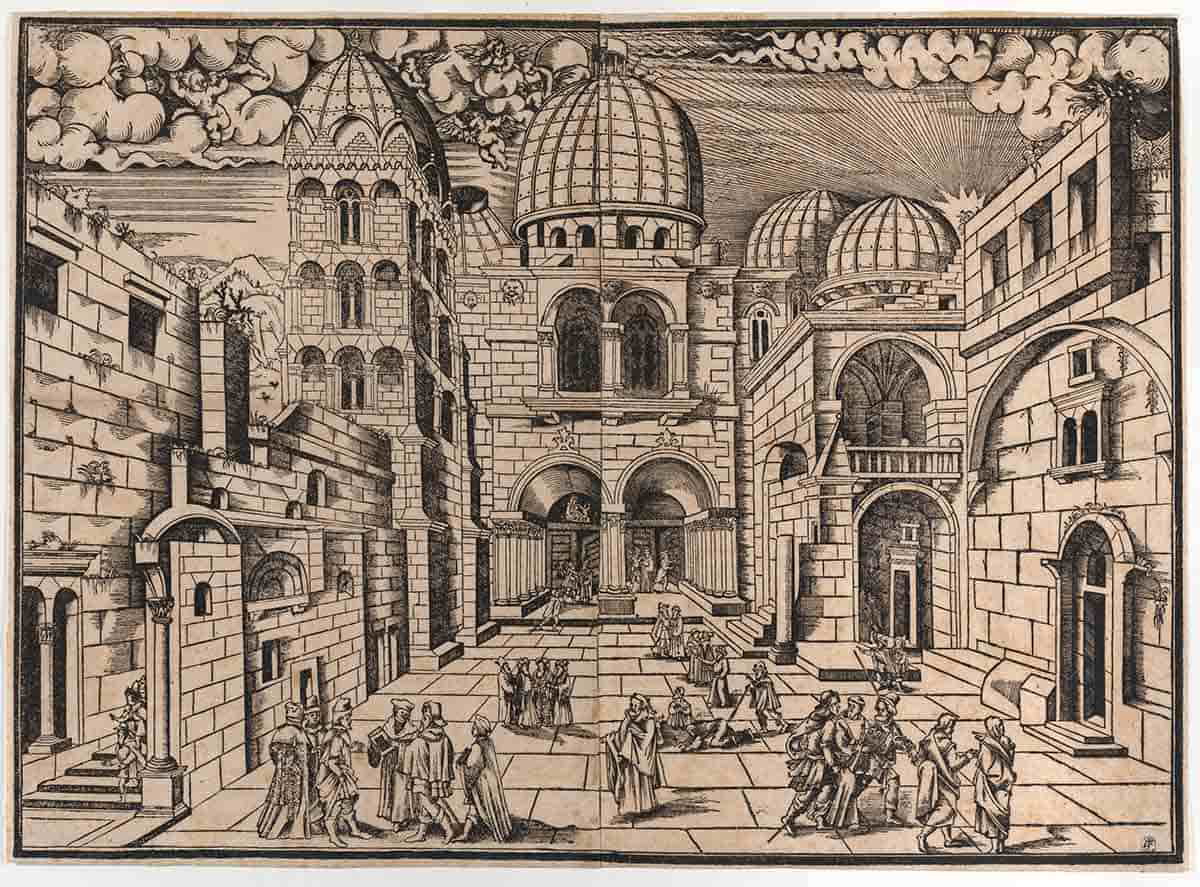

In 1095, Pope Urban II called for the First Crusade, ostensibly to help the Byzantine Empire against pressure from the Seljuk Turks. As the armed pilgrimage was underway, the target became liberating Jerusalem for Christendom. In 1099, after a brutal siege, the city fell to the crusaders. Rather than surrender control of the site to the Byzantines, the Catholic crusaders seized control of the location. Once securely in power, they began rebuilding the Sepulcher in the style of a Romanesque cathedral, a design that was popular in western Europe at the time. The new cathedral was larger and more elongated than the rounder Byzantine structure. It was also shaped in the form of a cross, a common motif found in Catholic churches. The new Church of the Holy Sepulcher was finally consecrated in 1149.

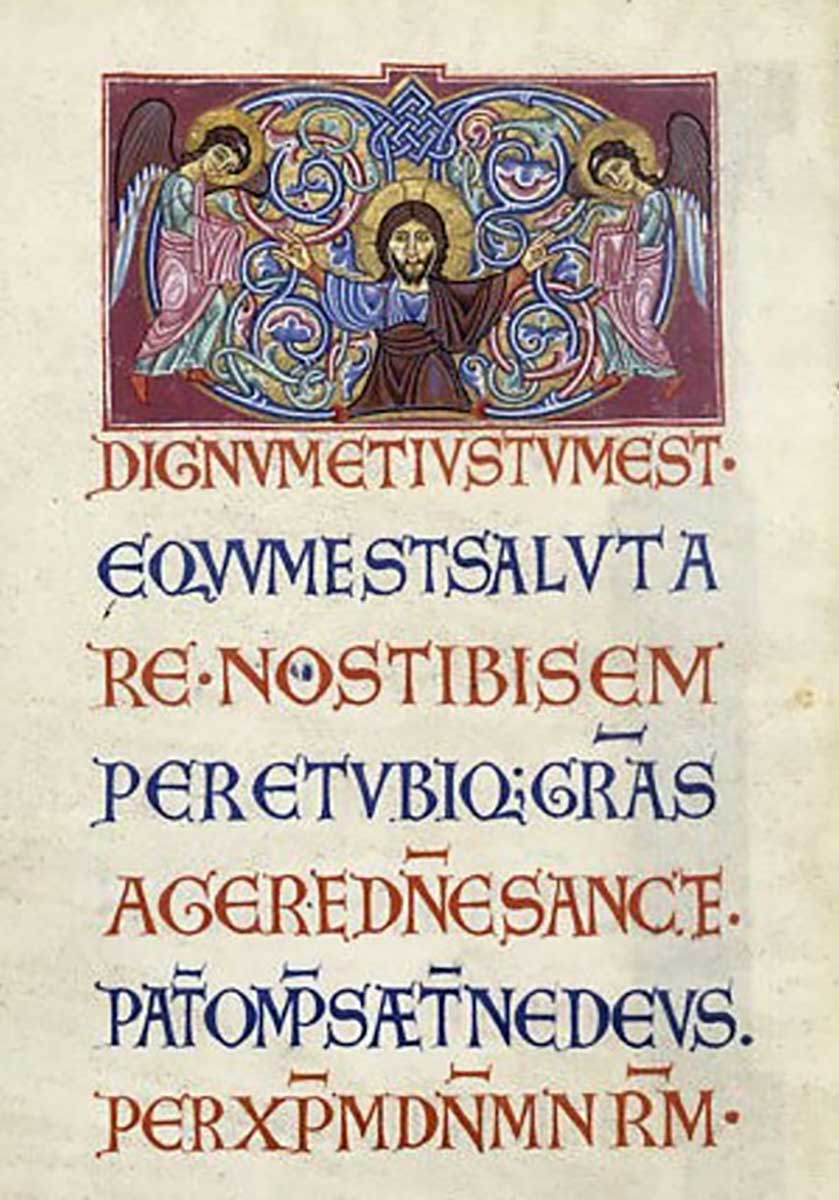

With the Sepulcher and Jerusalem under the control of Latin Christianity, it once again became a major site of pilgrimage. It was also made the seat of the Latin Patriarch of Jerusalem and housed the kingdom’s Scriptorium, the place where monks would transcribe books, a time-consuming and laborious task before the invention of the printing press. The sepulcher was also the burial location for at least eight of the Kingdom of Jerusalem’s monarchs, though these graves have been lost to history, probably destroyed by a fire in 1808.

Christian control over both the kingdom and the Sepulcher would eventually come to an end in 1187, when Islamic forces under the leadership of Saladin invaded the Kingdom of Jerusalem and captured the city. In response, European kings organized and launched the Third Crusade, aiming to regain control over Jerusalem. This would ultimately fail, though a treaty would allow pilgrims to travel to and worship at the church.

Knights of the Sepulcher

After the First Crusade captured the city of Jerusalem, the foundations of a new militant holy order were laid. The leader of the crusade, Godfrey of Bouillon, became the first ruler of the newly established Kingdom of Jerusalem. Godfrey, however, refused to be crowned king in the same place where Christ walked, so he settled on a much more humble title, Advocatus Sancti Sepulchri or Advocate of the Holy Sepulcher. He spent much of his short reign consolidating his kingdom and fending off outside threats, such as the Fatimids in Egypt. To help him in these difficult tasks, Godfrey instituted the Order of the Canons of the Holy Sepulcher. With Godfrey’s death in 1100, the throne would pass to his brother Baldwin, who was crowned king. In 1103, Baldwin assumed command of the Order, which was recognized by the pope in 1113.

The Equestrian Order of the Holy Sepulcher of Jerusalem was a militant holy order similar to other militant orders, such as the more famous Knights Templar and Hospitallers. All of these groups protected the Holy Land against outside threats, but the Knights of the Holy Sepulcher gave higher priority to defending the Sepulcher and other holy sites, rather than the broader mission of protecting pilgrims traveling from Europe. Their heraldry features a red Jerusalem cross, a variant of the cross that has a perpendicular cross piece at the end of each bar, surrounded by four other red crosses.

Although most of the Order’s operations were centered in the Holy Land, they also established priories throughout Europe to attract more recruits. During the turbulent history of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, the Knights of the Sepulcher fought in many battles and campaigns to protect the kingdom. Their direct guardianship over the Sepulcher ended in 1187 with the capture of the city by Saladin. The order continued to exist, but in a greatly reduced capacity, until 1291, when the last crusader stronghold in Acre fell. Though some knights participated in the Reconquista in Spain, for the most part, the militant activities of the Order ceased. The Order was revived, but with a mission based on charity, advocating for the rights of Christians in the Holy Land, and fostering religious and spiritual devotion, which it continues to this day.

Layout of the Sepulcher Today

After the Crusaders were driven from the Holy Land in 1291, the Sepulcher continued to be visited by Christian pilgrims, but the heyday of European pilgrimages was long over. The Romanesque building of the 12th century serves as the basis for the current structure, although major renovations were undertaken in the 16th century. In 1808, a major fire destroyed much of the building, including the collapsed dome, which required an extensive rebuilding project. An earthquake in 1927 also necessitated major renovations. Since then, the Church has, and continues to require, extensive maintenance to keep the nearly millennia-old structure intact.

The Church of the Sepulcher is believed to contain the locations where Christ was crucified, his body anointed, and buried before the resurrection, all in the same building. After passing through the gate on the outside, a visitor enters a courtyard flanked by chapels, with the main entrance located to the north. Almost directly in front of the entrance is the Stone of Anointing, where Christ’s body was prepared for burial. To the left is the Rotunda, where, surrounded by numerous chapels, the focus of the Sepulcher, and arguably all of Christianity, is located: the Tomb of Jesus. To the right of the entrance, there is a set of stairs that lead to the second level, and to Golgotha, or Calvary, the place where Jesus was crucified. The exact location can be seen today as a hole carved into the stone to accommodate a wooden cross underneath a Greek Orthodox altar.

Around the rest of the Sepulcher are many separate chapels, each one believed to be a location where significant portions of Christ’s crucifixion occurred. These include the place where Christ was kept as a prisoner with two thieves, where lots were cast for Jesus’ garments, and where the True Cross was found by St. Helena, the emperor Constantine’s mother. There are also chapels dedicated to various saints, such as Mary Magdalene and St. Longinus, as well as the tomb of Joseph of Arimethea. Directly under Golgotha is the Chapel of Adam, where tradition states that the blood of Christ dripped down onto the skull of Adam, the first human. The rest of the Sepulcher is divided into numerous chapels, monasteries, and other sacred locations.

Control of the Sepulcher and the Immovable Ladder

There are many Christian denominations today, so which one controls the Sepulcher today? Unfortunately, there is no easy answer. Currently, the denominations that claim control over the church are the Catholic Church, the Greek Orthodox Church, the Armenian Apostolic Church, the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the Coptic Church, and the Syriac Orthodox Church. Each one has claimed the Sepulcher as theirs to oversee, leading to near-constant bickering. This, for the most part, ended in 1852 due to a proclamation by the Ottoman Empire that divided the building between the sects, a state of affairs called the Status Quo. Some of the buildings are universal, owned collectively, while smaller chapels, monasteries, and annexes are controlled by each sect individually.

Generally, peace and tranquility are the norm in the church, with a complex series of rituals and procedures about who can travel to which section and under what circumstances. Still, tensions flare, and this can lead to outright violence. In 2002, a brawl broke out between the Coptic and Ethiopian monks over ownership of a part of the roof. To stake their claim, the Copts rotate a monk who sits in a chair to watch the roof. However, on a blisteringly hot day, the monk assigned to this role moved the chair about eight inches to find shade. This was taken as a violation of the Status Quo, and both sides came to blows, and eleven monks were sent to the hospital.

Then there’s the Immovable Ladder. It is a common wooden ladder, placed against an outside second-floor window sometime in the 1700s. No one knows who put it there or why, but to prevent an incident, it has remained propped against the wall, since one denomination moving it would be seen as a violation of the Status Quo. It’s not entirely immovable, having been moved several times, twice after being stolen, and once by mutual agreement to accommodate scaffolding during renovations. Each time it was removed, it was placed back exactly where it was, and will remain there for the foreseeable future. This otherwise innocuous ladder has become a symbol of the division over the Holy Sepulcher and Christianity as a whole.

With this internal fighting, the keys to the Sepulcher are in the most unlikely of hands. The keys to the most holy location in all of Christianity are held by a pair of Muslim families, who have held this position since at least the 12th century. Since they are not Christians, they are generally seen as a neutral party and can be trusted to be impartial. This is purely a symbolic gesture, but it demonstrates the complexity of the question of ownership of the Sepulcher.

This state of affairs has lasted for centuries and will almost certainly continue to do so for years to come. The center of Christian faith is at the forefront of division, an ironic state of affairs for the holiest place in the spiritual life of billions.