From its foundation in the 10th century to the decline of its influence in the early 12th, a program of reform and a renewal of monastic life unfolded at Cluny Abbey that would change Latin Christendom forever.

Cluny Abbey’s Independent Origins

In the heart of Burgundy in eastern France lies the town of Cluny. It seems on the surface a most obscure location, far from the traditional power centers that have driven the course of European history. Yet the Benedictine Abbey that once thrived here was for a long time the beating heart of western Christendom, with influence that spanned across the Latin West. The reforming movement that emerged in Cluny Abbey sparked a tumultuous cycle of Christian renewal whose effects would echo down the centuries.

The abbey of Cluny was founded in 910 (or possibly 909) by Duke William the Pious of Aquitaine. He required the monastery to follow the Rule of St Benedict, the established guide for the regulation of Christian monastic life in the West and insisted that the abbey was free from the imposition of any external authority.

This latter provision was important. Most monastic foundations were owned and controlled by the noble founder, with the appointment of abbots and any internal reforms overseen by said lord. This “Cluniac liberty” would play an important role in Cluny’s unique development, allowing the monks near-complete control of their own abbey.

Over the decades that followed, Cluny’s abbots would use their freedom to appeal to both the pope and the Frankish king for protection and privileges. Both of these figures guaranteed protection for the abbey and the independence of the monks, as well as affirming the monks’ control over the landed possessions belonging to the abbey. In effect, the monks, of whom there were around 100 at Cluny by the end of the 10th century, wielded lordship over the lands on which Cluny was situated just as a count or duke controlled their own lands.

Though medieval monasteries were places that in many ways sought to withdraw from the world, it is important to remember that they were the cultural centers of Christendom. They also had important connections to the nobility. Though Cluny was not tied to its aristocratic founder, the abbots, as at almost all medieval monasteries, were of noble birth, as were most of the monks.

The early abbots of Cluny were particularly well connected. Cluny was, therefore, an institution with important connections throughout the European noble class, and was thus able to generate influence and gain patronage even while being a place of withdrawal from the material world. It also benefited from a snowball effect — as the abbey grew in wealth and prominence, more and more of the nobility were keen to donate to the abbey in return for prayers for their souls.

From the beginning, Cluny sought to impose “renewal” onto other monastic houses as well as maintain a spirit of renewal within its own abbey. The abbots of Cluny used their influence within other houses across western Christendom to encourage reform, and in so doing to bring those houses closer to the central abbey at Cluny.

Papal bulls in the first half of the 10th century explicitly sanctioned the taking over of other monasteries by Cluny for the purposes of reform. “Reform” and “renewal” in this sense meant, paradoxically, looking back to the Rule of St Benedict and ensuring a closer following of this sacred model of monastic life.

A Monastic Revival

Monasticism was in a state of decline in the early 10th century. The early years of Christian monasticism in the deserts of North Africa, and the 6th and 7th centuries in Europe with the birth of the Benedictine Rule and the ascetic influence of the Irish monastic movement, were seen as a lost golden age of monastic discipline. The depredations of Viking raiders and a lack of rigor and discipline seemed to have deprived the monastic movement of that vigor. Cluny’s independence from laity control liberated it from the influences that many saw as depriving monasticism of its sacrality in this period. As the abbey grew in prominence, other monasteries that sought to free themselves from lay influence began to draw toward Cluny Abbey like moths to a light.

Another important contextual feature for Cluny’s rise was the vacuum in central power that existed in 10th and 11th-century Western Europe (and especially Francia). The king of the Franks exercised very little power outside of a narrow ring of territory surrounding Paris, with middling nobles vying for power in the rest of Francia. Meanwhile, the Roman Church had yet to develop the centralized power structure under the pope that would emerge so strongly in the 12th and 13th centuries. There was thus an absence of a structured, hierarchical institution that could bring order and stability to Western Europe. This may go some way to explain why Cluny developed such a strong attraction as it became larger and more influential.

The first century or so of Cluny’s existence saw it undergo a gradual accumulation of influence and renown. Its abbots held sway across numerous other monasteries that were beginning to be brought under the orbit of Cluny. Yet through the 11th century, under the supervision of two long-lived abbots, the monastery would rise to new heights of influence and prestige within Latin Christendom. Odilo (Abbot 994-1049) and Hugh (Abbot 1049-1109) oversaw a transformation in which Cluny, in addition to influencing other abbeys to reform themselves on a Cluniac model, began to develop a defined network of monastic institutions with Cluny Abbey at the center of this hierarchical structure.

Cluny’s independence from external control allowed it to become a “mother house” and take ownership of other monasteries. Scholars have created the term ecclesia Cluniacensis (ecclesia is Latin for church) to describe the new form of monastic order that emerged in the 10th and 11th centuries. Under Abbot Odilo, Cluny began to absorb an increasing number of houses. These houses had begun by adopting Cluniac reforms in their observance of the Rule, but they now became directly subject to the Abbot of Cluny.

Why would a monastery want to do this? In a world where most monastic houses were owned by lay lords, it was perhaps seen as a great liberty to enter a monastic church that was free from the corrupting influence of lay power, especially one that was dedicated to furthering the church and the Christian religion.

Under Odilo’s successor Hugh, the arms of Cluny grew to reach across Northern France, England, and Scotland, and down into Northern Italy and Iberia. In England, the Cluniacs worked alongside William the Conqueror to reform monasticism in England after the Norman Conquest, bringing it into line with practice on the continent. In Spain, the Cluniacs were eager participants in the process of Reconquista.

The pope was an ally in the growth of Cluny, and at the end of the 11th century, a papal bull extended all of the privileges granted to the Cluny mother house to any monastery within the ecclesia Cluniacensis. By the mid-12th century, there were around 700 Cluniac communities across Christendom, of varying size and structure.

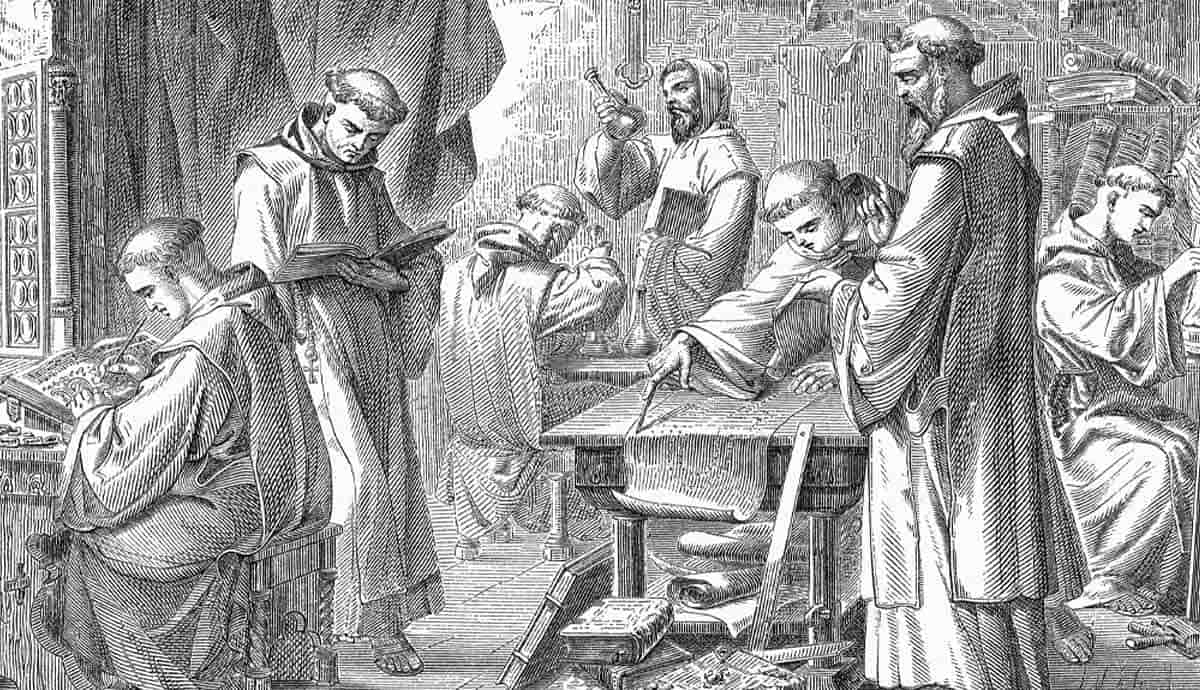

Aside from forging an independent organizational structure for monasteries, Cluny’s mission of reform made it imperative to create and spread a new form of monastic practice. The Rule of St Benedict provided only an outline of monastic life — the details of daily routine differed between monastic communities. Cluny developed its own order of monastic life. It contained specific customs of prayer and liturgy, work and obedience, and the denial of the body and the material world.

In the 11th century, Cluny’s practices began to be compiled into written texts. These were used by those founding new monasteries or reforming pre-existing ones to reshape communities along Cluniac lines.

The abbey itself was famed for the sheer volume of its prayers and services. Liturgies and prayers were constantly performed to remember deceased monks and benefactors. Contemporaries also noted that the abbey would feed hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of the poor every day. The abbots themselves became revered figures.

From Odilo onward the abbots commemorated their predecessors through hagiographies, and saints’ lives of the Cluny abbots became popular around Latin Christendom. A significant part of Cluny’s revered status lay in the status of its abbots, who were thought to embody the spirit of the entire Cluniac order.

Nobility throughout Christendom donated their wealth to Cluny. These donations were made in return for prayers said by the monks of Cluny for the salvation of the donator’s soul, and sometimes for a burial place within Cluny Abbey’s hallowed walls. The more renown that Cluny gathered, the more it became the most highly regarded Christian institution for those eager to access eternal salvation.

Equally, as Cluny became more highly regarded, powerful figures across Christendom were eager to prevent any one individual from gaining disproportionate influence over it. This allowed the Cluniac abbots to remain independent of any one patron and to pursue their own agendas.

The Ecclesia Cluniacensis

In 1088, the construction of a new church began at Cluny. It was to be one that reflected the influence and the prestige of the monastery within Christendom. It also needed to provide space for the 300 monks who by now had joined the abbey.

When constructed, Cluny’s church was the largest church in Western Christendom. It was constructed in the Romanesque style that was popular at the time (before the emergence of Gothic architecture in the later 12th century). The scale of this building solidified Cluny’s place at the center of Latin Christendom. It was the largest church in Western Christendom until the rebuilding of St Peter’s in Rome in the 16th century. Unfortunately, the abbey did not survive the French Revolution, and thus very little of this building can be seen by us today.

The grandiosity of the structure reflected the fact that the Cluniacs, for all their emphasis on individual poverty and simplicity, believed in celebrating the mass in awe-inspiring surroundings to reflect the glory of God on Earth. Later monastic movements like the Cistercians, who grew out of the Cluniac reform movement, would place greater emphasis on austerity in all things.

Cluny had emerged at a time when the Christian world had a vacuum of dynamic leadership. The papacy in the 10th century was the plaything of Roman noble families, and the era of Charlemagne, when great emperors could claim ultimate spiritual and secular leadership over most of western Christendom, was no more (despite the strength of the Ottonian Dynasty in the German lands and northern Italy). The revitalization of Christian leadership demonstrated by the Cluniacs inspired others, however, and in the mid-to-late 11th century, the papal reform movement surged into life.

Reforming popes, determined to transform the Roman church from the inside, were deeply influenced by the way in which Cluny instituted a disciplined hierarchical organization that spread throughout Europe. They took inspiration from how Cluny had sought to simultaneously impose order while fostering genuine spiritual renewal and renewed dedication to piety.

The charismatic leadership of Cluny’s great abbots, particularly Abbot Hugh (1049-1109), also seems to have influenced some of the key papal figures of this time like Gregory VII and Urban II. Indeed, the latter pope, who launched the First Crusade in 1095, was himself a former monk at Cluny Abbey.

Cluny’s Eclipse

The 12th century saw the relative decline of Cluny’s dominance within Western Christendom. A revived, powerful papacy gradually distanced itself from its alliance with the Cluniacs, while new monastic movements arose, attempting to seize the gauntlet of monastic renewal from Cluny. The revitalized Roman Church claimed to be the only mediator of salvation, leaving Cluny isolated. The Cistercians, emerging in 1098 around the abbey of Citeaux in Burgundy, asserted themselves as the new dynamic force in monasticism, dedicated to a stricter and more austere form of observation to the Benedictine Rule.

In addition, the sheer scale of the Cluniac order began to work against it, as the disparate flock of monks and nuns from across Christendom became harder to oversee by a single abbot and mother house. Unity could not be maintained for long and factions began to emerge within the Cluniac church. This was seen during an abbatial schism in 1122 when Abbot Pons was deposed and replaced by a successor who lasted only three months.

The Cluniac order was incredibly dependent upon the person of the abbot, whom some contemporaries even satirized as akin to a monarch. But such reliance upon an individual to hold together and guide such a vast and sprawling network of houses could not last forever. It also meant that the deaths of abbots, particularly long-lived abbots like Hugh the Great and Peter the Venerable, caused great disturbance in the Cluniac church and could sever connections with major nobles that had been reliant upon the abbot’s personal charisma.

Perhaps the last great abbot of Cluny was Peter the Venerable (1122-1156). Peter faced criticism of the Cluniac order from the emergent monastic orders like the Cistercians (including the mighty Bernard of Clairvaux) and played a prominent role in European religious debates, keeping Cluny at the front and center of Latin Christendom. He famously sheltered Peter Abelard, the controversial scholastic philosopher who gained fame and notoriety throughout the Christian world, and he granted him a posthumous absolution. Abbot Peter was also famous for his interest in the writings of the Islamic world, and it was he who published the first translation of the Quran into Latin after mingling with Islamic scholars in the Iberian peninsula.

Perhaps Peter the Venerable’s most important legacy for Cluny was his Statuta, a compilation of abbatial decrees and writings that sought to condense the Cluniac reform movement into a single text. This was composed alongside the holding of a number of general councils and together they sought to fortify the Cluniac order and maintain unity among its many houses and factions.

However, Abbot Peter oversaw the last great era for the Cluniac order. By the end of the 12th century, the Cluniacs had lost their privileged status at the vanguard of monasticism and as the darling of the Papacy. The Cistercians and the Papacy now dominated Latin Christendom, with the former soon to be challenged by another set of strident monastic orders—the Dominicans and the Franciscans—who would emerge in the early 13th century.

The Cluniac order did not fall apart after the death of Peter the Venerable in 1156. If anything it became more bureaucratized and orderly, with councils and mechanisms replacing charismatic abbots at the heart of the Cluniac church’s governance. However, it would never again be at the forefront of Western Christendom, either spiritually or politically. That is to say, the influence that Cluny once held, both as a spiritual model for Christians to admire and aspire to and as a key player at the papal court and the courts of Christian monarchs, was lost by the 13th century.

The Importance of Cluny

Why does Cluny matter? The rise of the Cluniac order can be seen as marking the emergence of Latin Christendom out of the stagnation and fragmentation of the Early Middle Ages and into an era of reform, unity, and confidence that marked the High Medieval Period in Western Christendom. The extent of the Ecclesia Cluniacensis also represents the unity that was a defining feature of medieval Europe prior to the emergence of powerful nation-states.

A monk of the Cluniac order could travel from the north of Britain down to the Pyrenees, and from the Atlantic coast deep into Germany, all the while passing through churches that followed the same practices, prayers, and daily routines, speaking the same language (Latin) and loyal to the same abbot.

The drive of Cluny Abbey to purify and perfect itself, and to lead a movement toward a more unified church, sparked a process that has arguably continued in Europe ever since. The Papacy and the Cistercians followed the Cluniac example, yet these were just the early movers in a cycle of Christian reform movements that ultimately led to the Reformation. In the pretenses of an obscure Burgundian abbey, one can see the factors that would drive European history from the High Medieval Period to the modern day: the relentless drive for self-perfection, the harkening back to a “golden era,” and the efforts to realize that era in the present day.