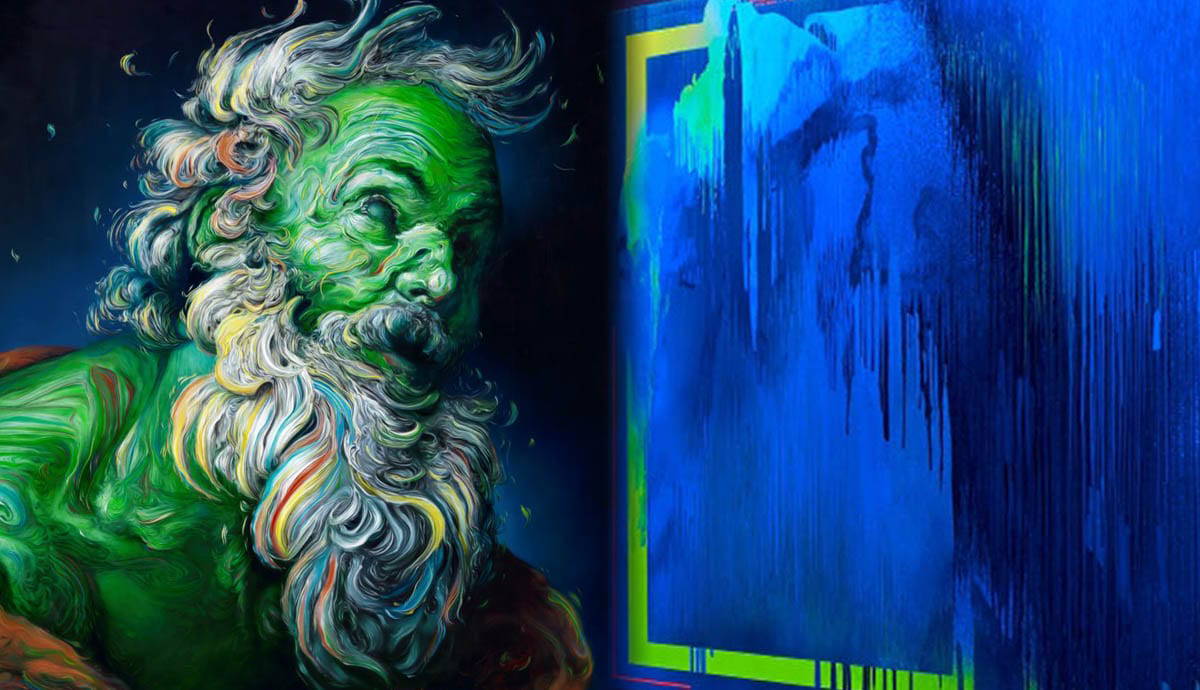

Digital painting is a marriage of opposites, uniting the gooey mess of paint with technology’s clean, polished veneer. With information technology at the tip of our fingers and screens lighting up our daily lives it is perhaps little surprise to see painters examining how they can be embedded into their artistic practice. From rudimentary printers and photocopiers to the latest computer coding, animation programs, or fluorescent paint, today’s digital paintings are ingeniously inventive, exploring the many ways computerized effects can be incorporated into a painted surface. Combining these digital techniques with an expressive, painterly language is a trope many of these artists have adopted, to remind us that beneath the glowing aura of digital light we are still messy, imperfect humans after all.

The History Of Digital Painting

Since the invention of photography in the late 19th century, painting has held a tricky relationship with technology. Expressive and abstract painting styles first emerged as an antidote to photography, proving paint could have an identity that was entirely separate from the shackles of representation, one that was innately tied to the subjective human experience. It wasn’t until the 1960s, with the advent of Pop Art and Photorealism that artists began to explore the concept of digital painting. One of the first to embrace a digital aesthetic was the Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein, who introduced the ink-saving ‘Ben-day’ dots of comic books into his art, enlarging them into dizzying patterns of color and light. His cool, detached language of mechanical dots appeared entirely machine-made but was in fact painstakingly hand-painted with flat magna paint through a metal stencil.

In the painting Brushstrokes, 1965 Lichtenstein enlarges the fragment of a comic book story titled ‘The Painting’, by Dick Giordano. The abstract design of his composition resembles that of New York’s Abstract Expressionist painters of the 1950s, but Lichtenstein deliberately parodies their supposed originality by rendering his abstract composition and dripping paint entirely synthetic.

In the wake of American Pop Art, an alternate group of artists who called themselves Capitalist Realists emerged in West Berlin, heralding themselves as “Germany’s first Pop artists.” One of the most prominent members to emerge was Sigmar Polke, who mined the worlds of media, advertising and popular culture for subject matter. But in contrast with the clean languages of American Pop, Capitalist Realists took a grittier and messier approach, combining the Expressionism of Germany’s past with elements of mass media imagery to create their own brand of digital painting.

Like Lichtenstein, Polke loved dots because they represented the printed page, but he took his from the deliberately cheap, messy process of enlarged photocopying. Polke pasted, printed, and painted these dots into many of his paintings, turning them into his own cheeky trademark style, as demonstrated in the painting Untitled (figure), 1963.

German painter Gerhard Richter was closely associated with Polke and the Capitalist Realist movement, sharing with Polke a mutual fascination in how the printed surface could be incorporated into painting. Richter is perhaps best known for his trademark blurred, photoreal paintings that mimic the softly focused lens of photography so well it is often hard to tell if they are really painted at all. His work was closely aligned with the American Photorealists of the 1960s and 1970s, who sought ways of painstakingly rendering the sharp realism of photography in painting.

But Richter took a more experimental approach, mixing photographic and painterly effects together to express his admiration for both mass media and the tactility of paint. In the 1970s, Richter began taking photographs of his own expressive, abstract paintings and making new paintings based on these photographs. As can be seen in Abstract Painting No. 439, 1978, the liquid fluidity of paint is merged with the glossy, pristine surface of the photograph to create a truly digital painting. Both Richter and Polke have had a particularly profound impact on today’s contemporary painters, who continue to expand on their playful, experimental approaches.

Found Imagery And Photography

Many of today’s painters take their subject matter from found photographic sources rather than direct observation, an attitude that reflects the infiltration of printed media into our daily lives. Some of today’s most adventurous painters deliberately highlight the digital nature of their source material, emphasizing the textures and surfaces of the original printed image and its cut or torn edges.

British artist Dexter Dalwood makes paintings that are based on his own small collages, deliberately reproducing sharply cut scissor lines or jagged rips with paint on canvas. Although his paintings often depict strange, illusionary places, as seen in Bay of Pigs, 2004, the jumbled up, cut and paste language of collage that constructs them reminds us that painting is still essentially a flat, two-dimensional object.

Like Dalwood, British artist Neil Gall enjoys rooting through the visual ephemera of daily life and working out how it can be incorporated into painting. His photoreal canvases are an eclectic and confusing mix of references, but we can often identify the crumpled pages of a glossy magazine nestled in amongst other random detritus from his studio. In Seen and Not Seen, 2013, magazine excerpts featuring women’s faces are almost visible, while he painstakingly copies in paint the sharp crumples of paper onto his photoreal surface.

Computers, Printers, And Photocopiers

Since Polke’s pioneering use of messy photocopies in the 1960s and 1970s, artists have continued to experiment with the playful dichotomy between digital printing and painting. American artist Wade Guyton makes works that typify the term digital painting, printing onto sheets of canvas with a large format Epson Stylus Pro 9600 inkjet printer. His trademark geometric designs of squares, x’s and grids are planned on a computer before being printed onto canvas, but what he enjoys most are the technical glitches that happen with the printer beyond his control, when the canvas gets stuck and has to be pulled out, or ink bleeds and overruns. These surprisingly painterly accidents reveal the creative, improvisatory possibilities within the supposedly clean, perfected language of inkjet printing.

Contemporary German painter Charline von Heyl works from found images, which she then obscures and abstracts through the process of painting. Since 2001, she has been experimenting with photocopiers and how they can distort and transform pre-existing imagery and provide her with an endless array of new material to work from to create her own brand of digital painting. She sometimes generates new images by painting on top of photocopies, as seen in the painting on paper, Untitled, 2003, which is an energized flurry of activity that seems part digital, part painted.

Screens And Moving Imagery

One of the most exciting artists making digital painting today is the American painter Jacqueline Humphries, whose paintings illustrate the digital languages of captcha codes, emojis, and computer programs. Her intricate repeat patterns of dots, dashes, x’s, and emoticons are painted through an industrial stencil cutter, which she then interweaves with expressionistic streaks of paint, marrying together digital painting with the unpredictable strokes of her hand. She compares this process of layering with the multi-screen activity of a computer, where we can view several pages simultaneously together, one on top of the other.

Her famous series of ‘black-light’ paintings further mime the aesthetic of glowing computer screens, painted with ultraviolet paint onto huge canvases that can only be seen in a darkened room lit by ultraviolet bulbs, lending her paintings what she calls a “cinematic quality.”

American abstract painter Amy Sillman is perhaps best known for her loose, improvisatory canvases made from networks of layered lines, shapes, and vividly hued colors, but she has also made spirited animations that bring her visual language to life. The animation work, Thirteen Possible Futures: Cartoon for a Painting, 2012 was made using an iPad drawing app, tracking the many different directions one of her paintings might take with a playfully humorous language. Sillman then printed out each frame of the animation and made them into a huge installation, allowing us to peek behind-the-scenes at the extensive decision making that goes into producing a single work of art.

The Future Of Digital Painting

As we move into a future of increasing technological development, there is little doubt that the scope of digital painting will continue to expand in new and exciting directions. British artist Glenn Brown sees the future role of painting as one that recycles and rehashes the art history of the past, remolding it into something new. His paintings copy and rework previous paintings old and new by a wide array of artists from Rembrandt van Rijn to Frank Auerbach, but he filters them through a digital screen, lending them an eerie atmosphere of digital light. He asks us to consider what the future function of painting can be in the post-digital age when we are so entirely surrounded by screens, but still have so much to gain from experiencing the raw physicality of a real painting.