Friedrich Nietzsche was one of the most controversial philosophers and writers of the 19th century, and his work continues to exert an enormous amount of influence over later philosophers. This article will focus primarily on one of Nietzsche’s most important essays, ‘On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense’.

The point is not to distinguish these concepts from one another, or to assess Nietzsche’s conceptualization of truth, but simply to explain how he draws his seemingly radical conclusions. We will begin with a discussion of Nietzsche’s life, the relationship between his life and his work, and the importance of distinguishing great philosophical personas from their ideas. Nietzsche’s polemics against knowledge moves to his concept of dissimulation, explores the notion of truth as access to the reality in itself, discusses the contingency of language in Nietzsche’s work, and finally concludes with an analysis of the role of art in Nietzsche’s thought.

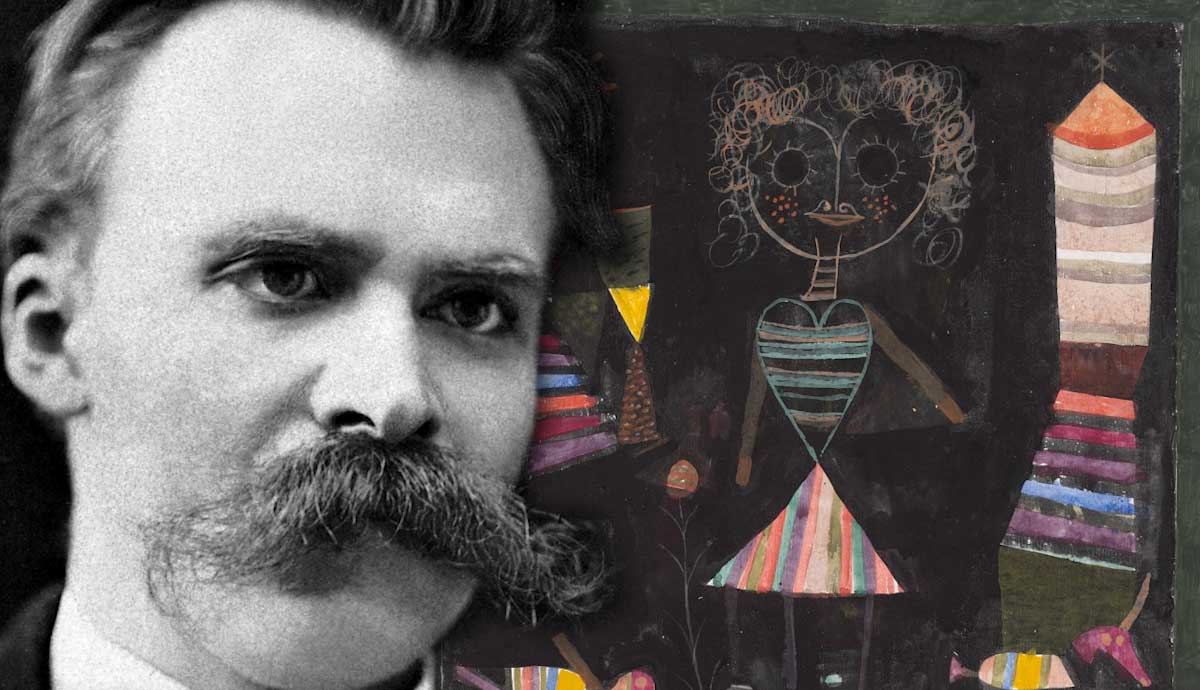

Friedrich Nietzsche: Life and Work

Most modern-day philosophers are academics, and academics tend to be relatively quiet, moderate, uninteresting people. However, Friedrich Nietzsche is one of a relatively small group of philosophers whose personality often seems to overshadow the contents of his thought.

His life epitomizes the intensity and loneliness of the stereotypical genius: from becoming the youngest full professor in Classics ever, at the age of 24, to his early retirement from academia and the intellectual isolation which followed, to his illness and his madness. Yet Nietzsche’s life was not, in the last analysis, so greatly dissimilar to many well-off, 19th century intellectuals. He cannot claim, as certain other philosophers can (strangely, John Rawls among them), that his philosophy is informed directly by certain extraordinary experiences.

His life story is interesting and it is tragic, but not uncommonly so. Despite the cultish misunderstandings which have followed Nietzsche and his work since his death, it might be better to leave aside any biographical interlude and focus intently on what he actually said.

1. Friedrich Nietzsche on Knowledge

‘On Truth and Lie’ begins as a polemic against knowledge, observing that knowledge is intrinsically related to human life and no other part of it, and that there are eternities on either side of human existence which are impassive towards all parts of that existence, including human knowledge.

“Once upon a time, in some out of the way corner of that universe which is dispersed into numberless twinkling solar systems, there was a star upon which clever beasts invented knowing. That was the most arrogant and mendacious minute of ‘world history,’ but nevertheless, it was only a minute. After nature had drawn a few breaths, the star cooled and congealed, and the clever beasts had to die. – One might invent such a fable, and yet he still would not have adequately illustrated how miserable, how shadowy and transient, how aimless and arbitrary the human intellect looks within nature.”

What Nietzsche feels the need to emphasize at the outset is that the concept of knowledge (or, at the very least, the significance often attributed to it, especially by philosophers) is an act of ego as much as it is an act of judgment. He observes that, “this intellect has no additional mission which would lead it beyond human life. Rather, it is human, and only its possessor and begetter takes it so solemnly – as though the world’s axis turned within it. But if we could communicate with the gnat, we would learn that he likewise flies through the air with the same solemnity,1 that he feels the flying center of the universe within himself.”

The philosopher is the culmination of this more general human tendency; Nietzsche describes the philosopher as the ‘proudest of men’ precisely because he is “telescopically focused on his action and thought”. Much of Nietzschean thought is anti-Platonic, and this clearly runs against one of the most famous Socratic maxims). Nietzsche appears willing to contest the view that the ‘unexamined life is not worth living’.

2. Dissimulation and Metaphor

In spite of dissimulation, the drive for mutuality, for existence ‘with the herd’ leads to a version of truth, which is effectively adherence to the conventions of language:

“… a uniformly valid and binding designation is invented for things, and this legislation of language likewise establishes the first laws of truth. For the contrast between truth and lie arises here for the first time. The liar is a person who uses the valid designations, the words, in order to make something which is unreal appear to be real. He says, for example, ‘I am rich,’ when the proper designation for his condition would be ‘poor.’ He misuses fixed conventions by means of arbitrary substitutions or even reversals of names.”

The upshot of this is the replacement of truth in itself with a kind of truth which is comprehensible only in relation to the conventions of language at a certain point. Truth cannot transcend the linguistic (and therefore social and cultural) context in which it arrives, nor even gesture at something beyond that context.

Nietzsche wants to clearly distinguish his approach to truth from that which holds that language allows us access to things beyond language, to things “in themselves”, and that it is that access which allows us to distinguish certain sentences as ‘true‘.

“The various languages placed side by side show that with words it is never simply a question of truth, never a question of adequate expression; otherwise, there would not be so many languages. The ‘thing in itself’ (which is precisely what the pure truth, apart from any of its consequences, would be) is likewise something quite incomprehensible to the creator of language and something not in the least worth striving for. This creator only designates the relations of things to men, and for expressing these relations he lays hold of the boldest metaphors.”

Metaphors are what carries over from different spheres of perception; that is the transference of sense, or some version of it, across the various senses. For Nietzsche, this is an explicitly physical process, and he defines it in distinctly biological terms: “to begin with, a nerve stimulus is transferred into an image: first metaphor. The image, in turn, is imitated in a sound: second metaphor. And each time there is a complete overleaping of one sphere, right into the middle of an entirely new and different one.”

3. Truth as ‘A Mobile Army of Metaphors’

In spite of the ephemerality of the ‘in itself’, Nietzsche argues that the manner in which we delude ourselves into mistaking the contingencies of language for the certainties of reality lies in the manner by which we arrange the conventions of language.

In making this point, Nietzsche also offers one of his many subtly different definitions of truth (in ‘On Truth and Lie’ and elsewhere) which has proven the most influential, particularly for philosophers in the latter half of the 20th century. It is as follows: truth is “a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms—in short, a sum of human relations which have been enhanced, transposed, and embellished poetically and rhetorically, and which after long use seem firm, canonical, and obligatory to a people: truths are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are; metaphors which are worn out and without sensuous power; coins which have lost their pictures and now matter only as metal, no longer as coins.”

It is the double movement by which language is first developed into an extravagance which looks like it might transcend beyond itself, and then all of those particular embellishments are stripped away in time, that construct the appearance of truth which speaks to reality itself.

4. Nietzsche on Metaphor and Art

How does Nietzsche suggest we cope with the realization that what we call truth is utterly contingent? He does not, as other philosophers might, feel that abandoning the concept of truth is so unthinkable as to preclude consideration even when it might seem appropriate to do so. In fact, he advocates precisely the opposite approach; an immersion in the self-consciously untrue realm of art.

In the Gay Science, Nietzsche argues that “if we had not welcomed the arts and invented this kind of cult of the untrue, then the realization of general untruth and mendaciousness that now comes to us through science—the realization that delusion and error are conditions of human knowledge and sensation—would be utterly unbearable. Honesty would lead to nausea and suicide. But now there is a counterforce against our honesty that helps us to avoid such consequences: art as the good will to appearance”.