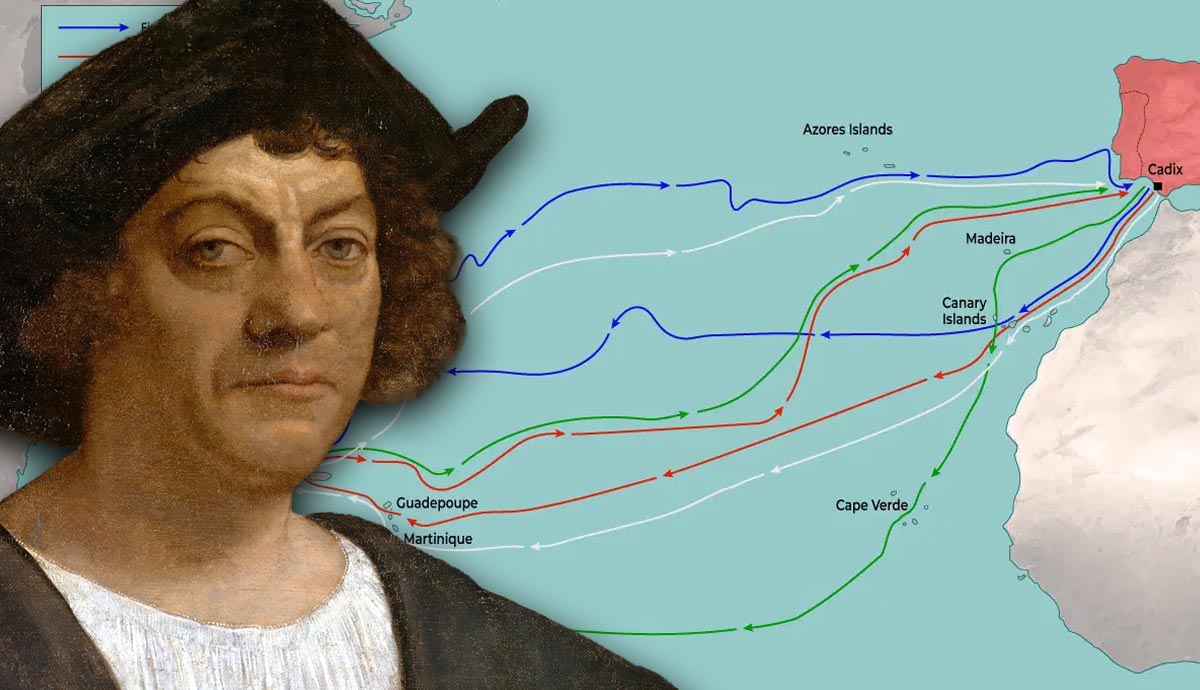

In 1492, Italian-born navigator Christopher Columbus, one of the most famous explorers of the Age of Exploration, set sail from Spain with the aim of finding a westward sea route to the East. Landing on an island in the present-day Bahamas, he was convinced to have made landfall in China, still unaware of the existence of a continent between Europe and Asia. Over the following years, he made three other voyages to the West Indies, hoping to find gold and secure his fame. Read on to discover more about Christopher Columbus and his four voyages.

The Spice Trade, World Maps, and Calculations

Portugal’s expeditions to the African continent’s west coast were driven by a series of factors, including the desire to explore, a Christian missionary fervor, and the hope of finding a sea route to the East and its spice islands.

In the Middle Ages, spices were among the most lucrative and sought-after luxury products. “High prices, a limited supply and mysterious origins fueled a growing effort to discover spices and their source of cultivation. Thus, spices were a global commodity centuries before European voyages,” explains Yale University Professor Paul Friedman.

While the spice trade was a “global economic network,” medieval Europe had only a vague sense of where the spices came from and how they were harvested. While accounts from European travelers, such as Marco Polo and John Mandeville, expanded the geographical knowledge of the East, their travel books were still full of fabricated information. Indeed, many medieval world maps often placed India close to the Garden of Eden, as cartographers combined Biblical and prophetic stories with inaccurate accounts.

When Marco Polo visited the East, the pax mongolica (Mongolic Peace), a period of stability during the height of the Mongol Empire, allowed for relative freedom of travel. As a result, in the 13th and 14th centuries, people, ideas, and goods were exchanged through Central Asia, giving the Europeans an unprecedented opportunity for travel and trade.

As the Mongol Empire weakened and the Ottomans conquered Constantinople (1453), leading to the fall of the Byzantine Empire, the traditional trade routes became hard to access for European merchants. As a result, by the 15th century, the European spice trade became dependent on a network of markets and routes largely controlled by Muslim powers. Over the following decades, the European powers began to search for alternative routes that would lead them directly to the East and its spices.

In 1487, Bartolomeu Dias sailed around the present-day Cape of Good Hope. Ten years later, Vasco da Gama followed the same route to reach India, securing Portugal’s monopoly on the spice trade. The desire to challenge the Portuguese hold was a significant factor in Queen Isabella’s decision to back Columbus’ voyage, an enterprise that sought to find a way to reach China and Japan by sailing westward through the Atlantic Ocean.

In the 15th century, the leading advocate for a sea route west to Cathay (China) was Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli, a Florentine mathematician and geographer. “From Lisbon directly westward there are in the chart twenty-six spaces, each one of which contains 250 miles, as far as the great and noble city of Quinsai [present-day Hangzhou], as well as at Cipango and Cathay,” claimed Toscanelli in a 1474 letter that Columbus consulted before his voyage.

Besides being unaware of the existence of another continent between Europe and Asia, Toscanelli’s calculations underestimated the actual distance between Lisbon and Japan, believing it consisted merely of 6,500 miles. Toscanelli based his theory on the Greco-Roman astronomer and geographer Ptolemy’s idea that the Earth has a small circumference. Combining these erroneous calculations, Columbus reduced the distance between Japan and the Canary Islands by about one-third.

Who Was Christopher Columbus?

Christopher Columbus was born Cristoforo Colombo in 1451 in the Italian seaport city of Genoa. His father, Domenico Colombo, was a merchant and wool worker. After Cristoforo, Domenico and his wife, Susanna Fontanarossa, had four other children: Bartolomeo (Bartholomew), Giovanni Pellegrino, Giacomo (also known as Diego), and Bianchinetta.

Little is known about Columbus’ youth, and even his origin is disputed, with some claiming he was of Catalan or Portuguese descent, rather than Genoese. According to a group of researchers who studied a DNA sample taken from his tomb, Columbus was a converted Jew from Spain. The vast majority of scholars, however, believe the explorer was born in Genoa, citing as evidence archival documents from Genoa’s Archivio di Stato (state archive), especially his 1498 testament.

Around 1477, Christopher and Bartholomew moved to Lisbon, where they worked as chartmakers and trade agents for the Genoese firm Centurione. In 1478, Centurione sent Columbus to Madeira, where he bought sugar, a sought-after product at the time. The following year, he married Felipa Perestrello e Moniz. In 1480, the couple had a son, Diego. Around 1488, Columbus fathered a second son, Ferdinand, with his mistress, Beatriz Enríquez de Harana of Córdoba.

By then, Portugal had already explored the west coast of Africa. In the first half of the 15th century, Prince Henry “the Navigator,” with the assistance of a group of skilled geographers and seamen, launched a series of expeditions that brought the Portuguese to Madeira, the Azores, and the Cape Verde Islands.

In the 1480s, Christopher Columbus made several trips to tropical West Africa, trading on the Guinea and Gold Coast and gaining knowledge of the Portuguese navigation system. However, when he asked King John II of Portugal to fund his project of finding a westward sea route to the East, the Portuguese monarch refused. In 1486, the Genoese navigator began seeking patronage at the Spanish court.

Six years later, in January 1492, he finally succeeded in securing the patronage of King Ferdinand of Aragon and Queen Isabella of Castile. By the terms of the Capitulations of Santa Fé, signed in April, Columbus was named “Admiral of the Ocean Sea,” viceroy and governor general of all the lands he would “discover” on his journey.

The First Voyage

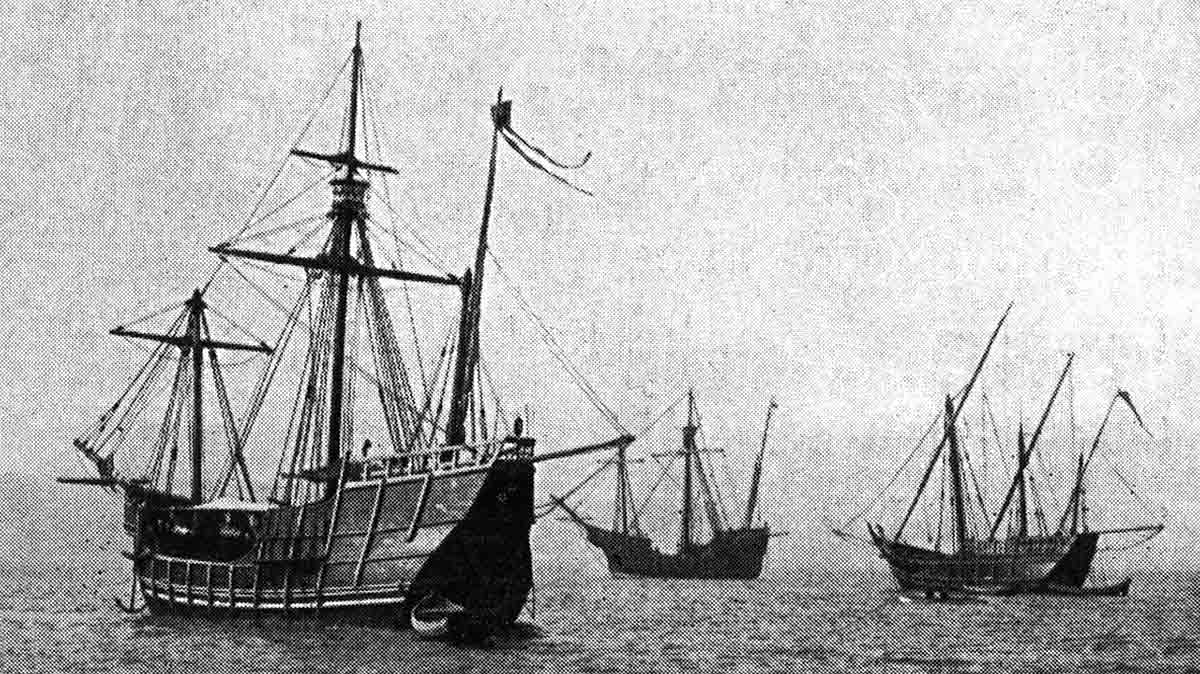

On August 3, 1492, Christopher Columbus sailed from Palos with a fleet of three ships, the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María. Not unlike the Spanish monarchs, the Italian-born navigator was driven by a mix of desire for adventure and prestige and a Christian missionary fervor. Just seven months earlier, the fall of Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian Peninsula, had ended the Reconquista, creating a wave of religious euphoria among Christians.

Columbus, who was present at the siege of Granada, directly referenced the Reconquista in the letter opening the journal of his first voyage: “I saw the Moorish King come forth from the gates of the city and kiss the royal hands of your. Highnesses, and of the Prince my Lord.” He then commented on the missionary aim of his voyage, declaring that the monarchs “resolved to send me, Cristobal Colon, to the said parts of India to see the said princes, and the cities and lands, and their disposition, with a view that they might be converted to our holy faith.”

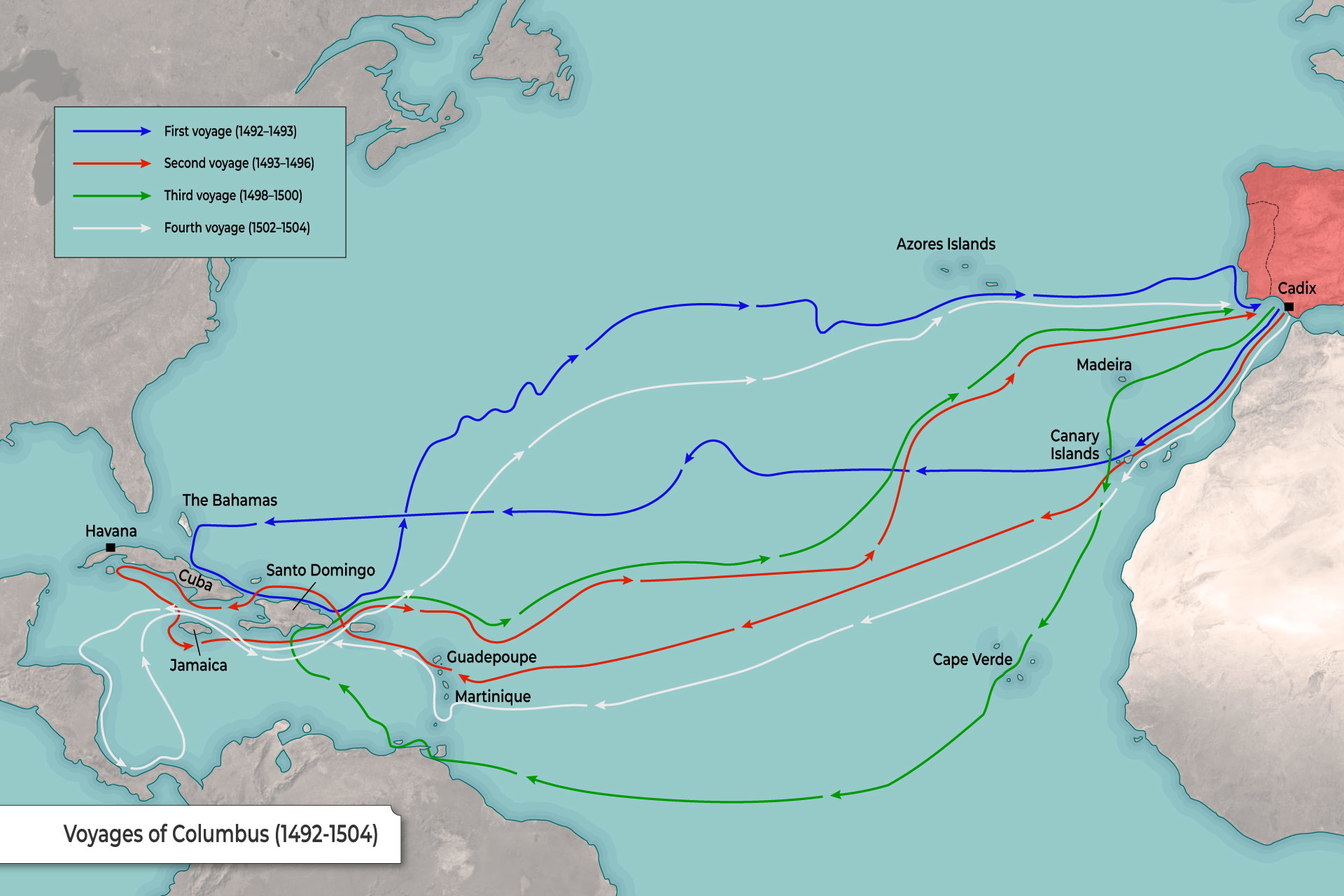

After sailing to the Canary Islands, Columbus began his crossing of the Atlantic Ocean on September 6, 1492. More than a month afterward, when the crew had begun to feel restless and provisions were low, Columbus finally sighted land on October 12, making landfall on one of the islands of the Bahamas, most probably San Salvador.

On October 28, the fleet arrived in present-day Cuba, a location Columbus initially believed to be Cipangu (Japan). He then became convinced it was actually Cathay (China). Over the following months, Columbus searched for the city of Zaiton (Quanzhou), China’s greatest and most famous port in the 13th and 14th centuries, when Marco Polo traveled throughout Asia. In December, adverse winds carried the navigator and his fleet to present-day Haiti, renamed by Columbus La Isla Española (Hispaniola).

On the island, Columbus found gold with the help of the Taìno, the native inhabitants of Hispaniola/Haiti and one of the most numerous indigenous peoples of the Caribbean. After setting up a stockade and leaving 39 men to guard it, Columbus began his return voyage on January 16, 1493. A few days earlier, the Pinta, commanded by Martín Alonso Pinzón, had joined the rest of the fleet after a less than two-month desertion. This event was not the only instance of tensions between Columbus and his crew, whose men often resented the explorer’s autocratic leadership.

After a difficult journey, during which a storm forced the Niña to seek harbor in the Portuguese-controlled Azores, where the crew was imprisoned by Portuguese authorities, Columbus landed in Palos on March 15, 1493. Upon reaching Navidad, the stockade built a year earlier, the admiral was shocked when he found it in ruins and the garrison left to guard it dead.

After spending the following year exploring the Cabo Valley, the Cuban coastline, and Jamaica, Columbus returned to Hispaniola in 1495 and began a ruthless conquest of the island, causing widespread devastation among the local Indigenous people.

The Second Voyage

While Christopher Columbus had failed to find the fabled gold- and spice-laden cities of the East, the amount of gold, spices, exotic birds, and captives he paraded upon his return was enough to convince the Catholic Monarchs to fund a second voyage to the “Indies.”

On September 25, 1493, Columbus sailed for a second time to the West Indies. On that day, a fleet of at least 17 ships left the port of Cádiz (Spain). The crew included about 1,300 men. Among them was also a group of friars, a testament to the underlying missionary aim of the voyage.

After sailing to the Canary Islands, the fleet landed in Dominica in the Lesser Antilles on November 3, 1493. Twenty days later, Columbus was back in Hispaniola. His harsh methods of governance also provoked resentment among his crew, with many complaining about his lack of trust, inflexibility, and an autocratic attitude fueled by the belief that he was the bearer of a divine plan destined to expand the borders of Christendom.

During his second voyage, Columbus also made his men swear that Cuba was, beyond any doubt, mainland China—an indication that, while he needed to prove the success of his expeditions, not all agreed with him.

After leaving his brothers Bartholomew and Diego in charge of the Spanish settlement in Hispaniola, Columbus set sail for Spain in March 1496. On June 11, he returned to Cádiz and immediately began lobbying for a third voyage.

The Third Voyage

While Columbus’ second voyage yielded less than satisfactory results, Ferdinand and Isabella decided to fund a third expedition. By then, the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas had divided the Atlantic Ocean between Spain and Portugal, giving Spain the lands west of a line 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde Islands. However, the agreement did not cover the opposite side of the globe, where West and East were supposed to meet.

On May 30, 1498, Columbus left Spain to sail across the Atlantic for a third time. The main goal of this third voyage was to find a strait that would lead to Cuba—believed to be Cathay (China)—to India. On July 4, the six ships under the admiral’s command left from Sâo Tiago in Cape Verde for Hispaniola.

After stopping at Trinidad, the fleet then reached the Gulf of Paria, where Columbus planted a Spanish flag on the Paria Peninsula. Over the following months, the El Corréo explored the Grande River, and, seeing the amount of fresh water flowing into the Gulf of Paria, Columbus guessed the existence of a new continent nearby. However, he failed to find a strait leading to India and returned to Hispaniola.

Upon his return, the island was experiencing a wave of political instability, with Indigenous people and Spaniards growing frustrated by Columbus’ brothers’ autocratic rule. While the navigator tried to put an end to the rebellion, Francisco de Bobadilla, the Spanish chief of justice, was sent to the colony to investigate the situation and address the complaints against the Columbus brothers.

In his report of the second voyage, Columbus blamed the tense atmosphere on sickness, a lack of provisions, and the resistance of the natives to Spanish rule. However, the exploitation system set up by Christopher and Bartholomew must also be taken into account. Indeed, under their rule, the Tainos were enslaved and forced to mine gold or shipped to Europe. During his governorship, Bartholomew increased dissent among the natives by taking direct charge of the mining activity, replacing the previous policy that tasked local chiefs with delivering a certain amount of gold.

When Francisco de Bobadilla arrived at Hispaniola, he ruled against the Columbus brothers, who were then sent back to Spain in irons. They landed at Cádiz in October 1500.

The Fourth Voyage

During the return voyage, Christopher Columbus wrote a lengthy letter to Ferdinand and Isabella, in which he presented his exploration of the West Indies in biblical terms. He even claimed to have found the location of the Earthly Paradise while sailing to Trinidad and the Gulf of Paria, as the weather became mild and the polestar’s rotation gave him the impression of sailing upwards. In his missive, Columbus also defended his actions as governor and declared he was close to finding the gold-landen realms near the Paradise.

Upon his return to Spain, Columbus managed to secure his release, and in December 1500, he was granted an audience with Ferdinand and Isabella. While the monarchs did not reappoint him as governor, they agreed to back a fourth voyage to the West Indies. In October of the following year, Columbus was busy preparing for the upcoming trip. Meanwhile, he began compiling the Book of Prophecies, a compilation of apocalyptic revelations, and the Book of Privileges, a list of his family’s titles and claims.

In the midst of this religious fervor and desire for glory, Columbus sailed with four ships from Cádiz on May 9, 1502. About two months later, he reached Martinique, but when he demanded entry to Santo Domingo on Hispaniola, his request was refused. He then sailed southward, exploring the coast of Jamaica, Cuba, Honduras, the Mosquito Coast of Nicaragua, and Costa Rica between July and September 1502.

In February 1503, he began to establish a trading post on the Belén River. However, he was soon discouraged by the hostility of the natives and the poor conditions of his two remaining ships. He thus decided to sail back to Hispaniola. During the return voyage, however, disaster struck, and he had to beach his ships on the Jamaican coast. Castaway by June 1503, Columbus and his men did not see any rescuers until June of the following year.

Disappointed by the outcome of his fourth voyage, Columbus returned to Spain on November 7, 1504, only to discover that his main patron, Queen Isabella, was close to dying.

The Legacy of Christopher Columbus’ Voyages

Until his death in May 1506, Columbus always declared to have made landfall in the East by sailing across the Atlantic. Whether he actually believed this or was, in fact, defending his reputation as an explorer and navigator is unclear. In 1521, when Juan Sebastián Elcano, Ferdinand Magellan’s second in command, completed the circumnavigation of the globe, Columbus’ claim to have reached China by sailing westward was once and for all disproven.

Nevertheless, Columbus was long celebrated as the “discoverer” of the Americas across Europe, where, as a result of his four voyages, the leading powers began building colonial empires in the “new continent.” More recently, however, the public and scholarly discourse has called for a more nuanced depiction of Columbus’ enterprise, emphasizing its disastrous effects on the Indigenous populations of the Americas.