In ancient Greek mythology, Helios was the embodiment of the sun and drove across the sky every day in his golden chariot, creating the day-night cycle. As the god of the sun, Helios was also associated with light, life, and truth. From his place high in the sky, he was said to see and hear everything his light touched. While he was a major cosmic force, Helios had very few temples across the Greek world compared with other gods. Over the centuries, he came to be increasingly identified with Apollo, who eventually overshadowed him completely in the Greek world.

Centers of Worship for Helios

Helios was worshiped throughout the Greek world, but his cult was less prominent than other Greek gods. In Athens, his priests were part of the harvest festival dedicated to Demeter and Persephone, owing to his role in the growth of crops. Yet, the ancient Greeks seem almost to have been neglectful of the god.

In Aristophanes’ play Peace, Helios and his sister Selene are represented as outsiders among the pantheon. This attitude was, in part, a repudiation of the Persians, who practiced a more naturalistic form of religion. Their main deities were those of the sun and moon, as opposed to the Greek pantheon, which was anthropomorphic in nature.

“Know then, that the Moon and that infamous Sun are plotting against you, and want to deliver Greece into the hands of the barbarians. […] Because it is to you that we sacrifice, whereas the barbarians worship them; hence they would like to see you destroyed, that they alone might receive the offerings.” (406-413)

However, there was a prominent center of worship for the sun god on the island of Rhodes. Helios was the patron deity of the island and was said to be the progenitor god of the Rhodians. Their coins were minted with his likeness. They also built a massive statue in the god’s image, the Colossus of Rhodes, which became one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Unfortunately, it was toppled by an earthquake 66 years after its construction. An oracle told the Rhodians not to reconstruct it, but even in ruins, it was considered a wonder. In Rhodes, they also celebrated a festival to Helios called the Halieia. The festival was celebrated around the temple to the god, where horse and chariot races were held.

Appearance & Iconography

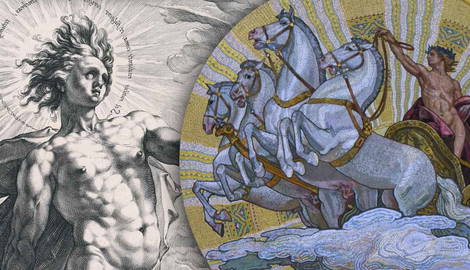

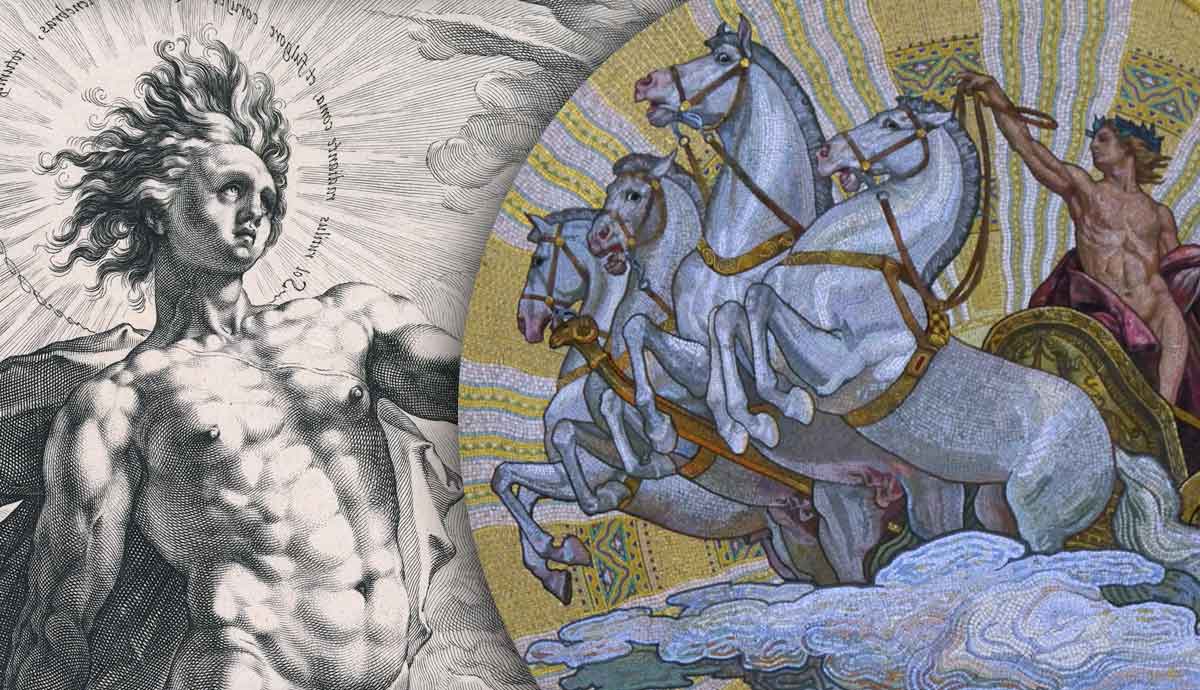

The Homeric Hymn to Helios provides the main literary description of the god. In it, he wore a golden helmet, and bright rays of light shone from him. He had golden hair that framed his face, and his clothes glowed and fluttered in the wind. His chariot was also golden and pulled by a team of four stallions.

There were rarely any sculptures of Helios, except for the Colossus of Rhodes, so most images of him come from vase paintings. Helios was typically depicted with a radiant halo or disc above or behind his head. He was also commonly shown riding his four-horse chariot out of the sea, from where he was said to rise every morning.

One of the few examples of a sculpture of Helios was on the east pediment of the Parthenon. There, Helios was located on the left side of the pediment, in the corner, coming out of the sea with four horses carved almost in the round. Although not much of the actual sculpture survives, the iconography of a chariot emerging from the sea is unmistakable, identifying it as Helios.

Helios’ Family

According to the 7th century BCE poet Hesiod, Helios was the son of the Titans Hyperion and Theia. He was one of three siblings, the others being Selene, goddess of the moon, and Eos, goddess of the dawn. Together, the three were said to shine their light upon all those on earth and the gods in heaven.

Helios had several children, the most notable of which were his son Phaethon and his daughters Circe and Pasiphae. Circe was featured in the Odyssey as the lone inhabitant of the island of Aiaia. She aided Odysseus by offering him guidance to get past the monstrous Scylla and Charybdis. She also warned him about his inevitable landing on the island of Thranicia, telling him not to eat the cattle he found there.

Pasiphae was the wife of King Minos and the mother of the Minotaur. Helios also had some children who were kings of various cities, although they were of lesser importance in the greater mythological tradition. All of Helios’ children were easily identifiable because they were said to have golden, flashing eyes just like their father.

Helios in Greek Mythology

Helios’ track across the sky, creating the day-night cycle, was his main purpose in mythology. He had a palace in the east, where he started his journey, as well as one in the west, where he finished. He then traveled the ocean in a golden cup to reach his palace in the east and begin the cycle again.

Helios plays only a minor role in various Greek myths. His light was said to shine upon everything, which led to the idea that he was witness to everything. In the story of Ares and Aphrodite’s affair, Helios was the one who saw the infidelity and told Hephaestus about it. He was also witness to Hades’ abduction of Persephone. In the Homeric Hymn to Demeter, when Demeter came asking after her daughter, Helios told her what happened and tried, poorly, to console her.

“Yet, goddess, cease your loud lament and keep not vain anger unrelentingly: Aidoneus, the Ruler of Many, is no unfitting husband among the deathless gods for your child, being your own brother and born of the same stock: also, for honor, he has that third share which he received when division was made at the first, and is appointed lord of those among whom he dwells.” (82-87)

A common theme associated with Helios’ role in mythology revolves around his cattle. The Gigantomachy, a war between the Olympians and the Giants that took place after the Titans had been defeated, began when the giant Alcyoneus stole Helios’ cattle. In Homer’s Odyssey, Odysseus and his crew land on Thranicia, the island where the god kept his cattle. Odysseus was warned not to eat the cattle, but when poor weather waylaid their journey home and his men started starving, they slaughtered the cattle and ate them. Helios reported the incident to Zeus, and when Odysseus and his men were finally able to sail off the island, Zeus struck their ship with a thunderbolt, killing everyone except for Odysseus.

The most prominent myth associated with Helios pertained to his son, Phaethon. He convinced his father to let him drive the chariot he used to cross the sky for a day, but he wasn’t able to keep control of the horses, who left their usual path. They first passed through the heavens, setting it ablaze, and created the Milky Way. After, they galloped down towards the earth, setting the lands on fire. Zeus stopped the chariot by killing Phaethon with a thunderbolt. Phaethon fell to the earth, landing in the Eridanus river, which is today the Po river.

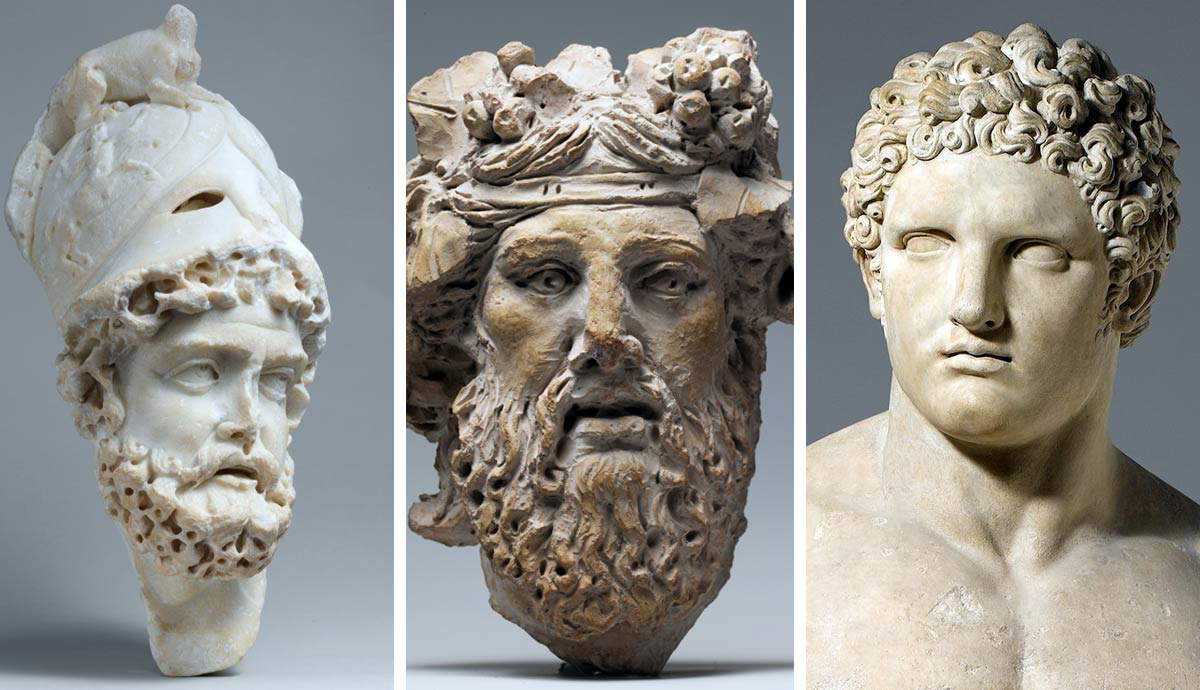

Helios Versus Apollo

By the Hellenistic period, Apollo had taken over many of the roles traditionally ascribed to Helios, to the point where Apollo completely overtook Helios in the role of sun god. Apollo was much more prominent after Alexander the Great’s conquests in the 4th century BCE. However, there is evidence that this was already happening in the 5th century and possibly even as early as the 6th century BCE. By the Roman era, Apollo had fully subsumed Helios’ place as sun god, as proven by Ovid’s version of the myth of Phaethon, where he was Apollo’s son instead of Helios’.

An early connection between Apollo and the sun comes from the 5th-century BCE tragedian Aeschylus. In The Seven Against Thebes, the playwright described the underworld as a sunless place “where Apollo does not walk.” Similarly, in the Odyssey, when Helios complained to Zeus that Odysseus and his crew had slaughtered his cattle, he threatened Zeus that he would descend into the underworld and shine upon the dead, implying that the underworld is a place he does not frequent. Clearly, in Aeschylus’ mind, and likely in the mind of the audience, there was a connection between the two deities to the point where they were interchangeable.

In one of Aeschylus’ lost plays titled The Bassarai, the general plot of which was recounted in Eratosthenes’ Catasterisms, the Thracian hero Orpheus stopped worshiping Dionysus for Helios, “whom he also called Apollo,” calling him the greatest of the gods. Here, there is an outright identification of Apollo as Helios.

The story of Hermes’ birth also borrows certain tropes from the myths of Helios. Recounted in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, the newborn Hermes raided the cattle of Apollo and hid them away in a cave in Pylos. There are parallel stories concerning cattle being driven to Pylos. During Heracles’ labor to drive off the Geryon cattle, he traveled to Erytheia, a land in the west where Helios was said to keep his cattle, using the cup that Helios used to travel the ocean at the end of his path through the sky. These cattle were then stolen from him by Neleus and driven to Pylos, where they were kept in a nearby cave. Neleus’ son Nestor also stole cattle from a descendant of Helios who ruled in Elis, driving them to the same cave in Pylos.

With this connection between Pylos and the cattle of the sun, we can infer Hermes’ theft of Apollo’s cattle belongs to this same tradition of theft of the cattle of the sun. Given that the Hymn expressly differentiates Apollo and Helios, it is likely that Apollo already possessed some identification with the sun, and thus, artists and poets could freely interchange the two to suit their needs.

Influence on Later Culture

Helios’ direct parallel in Roman culture was the god Sol, also known as Sol Invictus, the invincible sun. Sol shared the same iconography as Helios, with a solar disc around his head and riding in a four-horse chariot. However, even among the Romans, there was a tendency to equate Sol with Apollo. By the late Empire, the cult of Sol Invictus was the preeminent cult of Rome. It was only when the emperor Constantine had a vision of the Christian god and converted to Christianity that the imperial religion began to shift.

Christianity adopted many features of the cult of Sol Invictus, such as the halo, which is still used in many Christian images to depict divinity. The date of Christmas, December 25, can also be linked with Sol. This date was originally a celebration feast for Sol Invictus, placed on the winter solstice as the turning point in the year when the days begin to lengthen. Christ gradually subsumed the role of Sol Invictus in the state religion.

References

Bilić, T. (2021) “Early Identifications of Apollo with the Physical Sun in Ancient Greece: Tradition and Interpretation,” Mnemosyne, 74(5), 709–736.

Arnold, I. R. (1936) “Festivals of Rhodes,” American Journal of Archaeology, 40(4), 432–436.

Jeffrey M. Hurwit. (2017) “Helios Rising: The Sun, the Moon, and the Sea in the Sculptures of the Parthenon,” American Journal of Archaeology, 121(4), 527–558.

Segal, C. (1992) “Divine Justice in the Odyssey: Poseidon, Cyclops, and Helios,” The American Journal of Philology, 113(4), 489–518.