Napoleon Bonaparte dominated continental Europe as his French First Empire expanded at the start of the 19th century. Indeed, by 1808, Napoleon ruled an empire extending from Portugal to Poland. Napoleon’s army became the perfect instrument to execute the mobile and offensive style of war that military theorists dubbed “Napoleonic.” The army Napoleon forged was built upon ideas and innovations developed by French military theorists and commanders both before and during the French Revolutionary Wars (1792-1802). However, some of Napoleon’s strategies and tendencies contributed to the army’s defeat and his downfall.

Napoleon Bonaparte & the Royal and French Revolutionary Armies

In the 18th century, France boasted one of Europe’s largest and finest armies. However, defeat in the Seven Years War and mounting debts, stemming in part from France’s participation in the American Revolution, weakened the country’s military capabilities and helped set the stage for the French Revolution in 1789.

Moreover, the Revolution plunged the country’s army into a crisis of command and organization. In the early years of the Revolution, many aristocrats serving as officers resigned or even defected to join one of France’s enemies.

While initially this command shakeup weakened the military, it also paved the way for many capable ordinary soldiers to be promoted based on merit. One such commander was none other than the young Napoleon Bonaparte.

According to historian Gunther Rothenberg, Napoleon’s military strategies and organizational changes blended reforms and innovations suggested by others in the late 18th century (2006, 24). France, both before and during the Revolution, produced several prominent military theorists, including Lazare Carnot and Swiss-born Antoine-Henri Jomini.

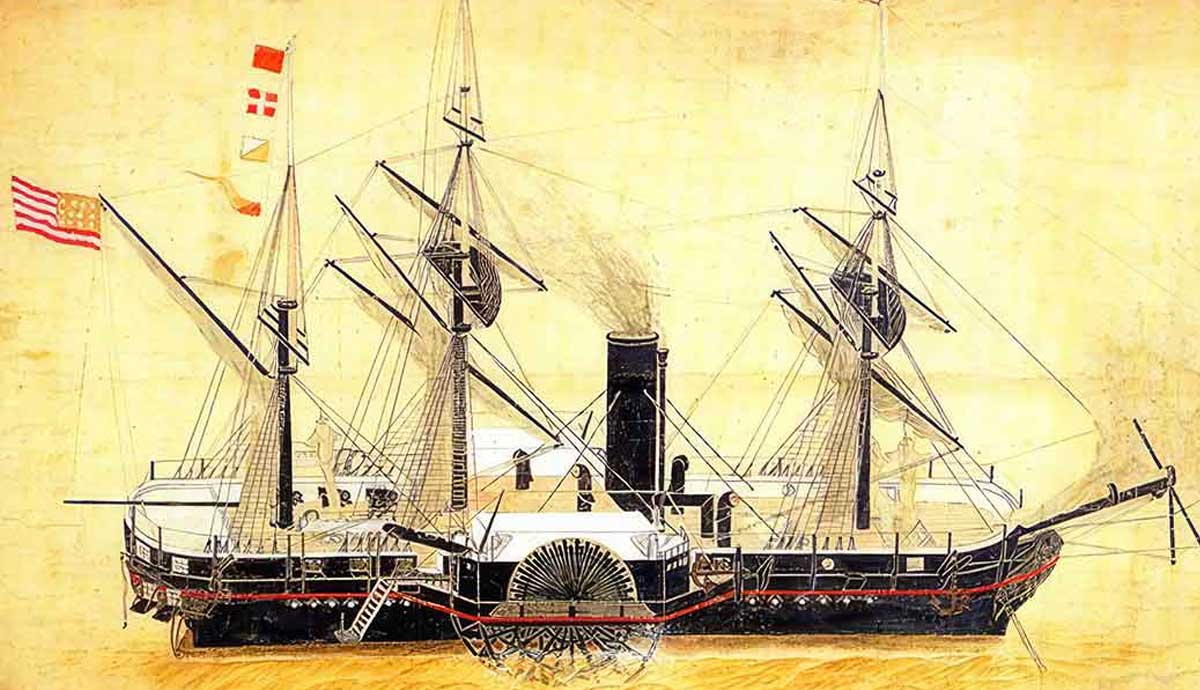

Moreover, French theorists were particularly strong in developing innovative techniques and approaches to artillery, including the Gribeauval system. Napoleon specialized in artillery during his military education.

Revolutionary France also built a modern conscription system to ensure the mass mobilization of French society for war, beginning with the Levée en masse in 1793.

Below, we’ll take a closer look at how Napoleon embraced and modified these earlier proposals as he built the Grande Armée.

Napoleon Bonaparte as Commanding General

Napoleon Bonaparte’s talent as a battlefield commander and propagandist was another crucial factor in France’s military success during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars.

Napoleon was constantly focused on attacking his enemies and staying on the offensive. According to Gunther Rothenberg, the French emperor fought only three battles in his career on the defensive, all of which occurred between 1813 and 1814 (2006, 36).

The success of most Napoleonic campaigns and battles depended on swift, long-distance marches and Napoleon’s ability to win meeting engagements. Historian J.P. Riley explains that a meeting engagement occurs when opposing forces on the march, lacking complete information about one another, unexpectedly collide. Napoleon generally welcomed chaos and confusion in the initial stages of battle (2000, 79).

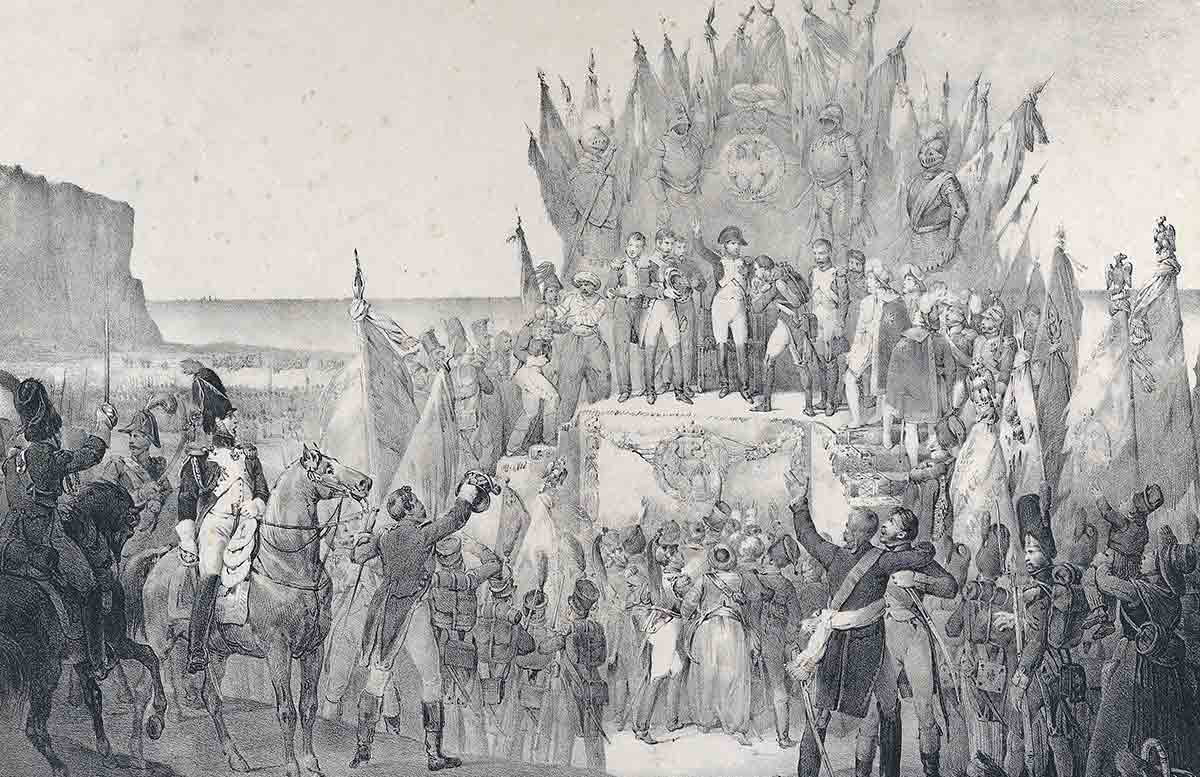

Propaganda was a key ingredient of Napoleon’s success as a commander. According to historian J. David Markham, Napoleon was a master of spin in our modern understanding (2003, 1). Beginning in Italy in 1796 and continuing throughout his career, Napoleon was involved in reporting his army’s exploits. As Markham explains, Napoleon founded a newspaper for his Army of Italy in 1796-1797, where he shared stories to boost troop morale and bolster support in Paris. He continued this tradition through the bulletins he issued as Emperor (2003, 2-3).

While he frequently exaggerated the extent of his victories and minimized his losses, Napoleon’s actual record on the battlefield was impressive. He also encouraged and sponsored engravings, prints, and even monumental art to tell the French people and the world about his exploits.

Organizational Innovations

Historian Gunther Rothenberg noted that the weapons, equipment, and troop types in the armies of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars remained largely unchanged from those of Frederick the Great’s army several decades earlier. What had changed was the size of the armies, their organization, and how armies were deployed (2006, 24-25).

Armies fought more battles in Europe during the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars than in prior conflicts. For example, historian Tim Blanning notes that 713 battles were fought over the 23-year period between 1792 and 1815. There had only been 2,659 battles during the preceding three hundred years (2007, 643). The sheer volume of battles suggests that Napoleon and his opponents sought a complete victory.

According to Gunther Rothenberg, this decisive outcome was dramatically different from the more limited objectives of earlier warfare in Europe. Most wars before the French Revolution ended without many bloody battles due to a lack of funds and resources (2006, 25).

Napoleon adopted new methods of organization, including the establishment of a permanent corps structure. Before Napoleon, commanders used corps temporarily.

A permanent corps structure essentially created miniature armies. This meant that each corps traveled along designated roads and had specific foraging areas to gather supplies. The permanent corps system thus permitted Napoleon to execute rapid, long-distance marches without clogging up roads and exhausting supplies.

In terms of organization, Napoleon benefited from the work of his chief of staff, Alexandre Berthier. Berthier became one of Napoleon’s marshals despite rarely receiving a battlefield command.

Napoleonic Warfare & Wars

The Napoleonic approach to war emphasized mobility, speed, and the concentration of superior numbers. The strategy behind this approach was to quickly and decisively crush enemy armies, thereby securing a rapid victory in a campaign or war.

Napoleon and other French officers of the era favored aggressive tactics. We can see evidence of Napoleon’s method of waging war from the onset of his career as a commanding general during the Italian campaigns of 1796-1797. Here, Napoleon split the opposing Austrian and Piedmontese armies and defeated them separately. In less than one month, Napoleon forced Piedmont to seek peace and laid the foundation for a successful campaign against the Austrians.

However, no campaign captured the essence of Napoleon’s way of war more than the Ulm-Austerlitz campaign of 1805. Historian Tim Blanning points out that the Austrian commander at Ulm, General Karl Mack, estimated it would take Napoleon’s army 80 days to reach his position. In reality, Napoleon’s troops covered the 300 miles (480 km) in just 13 days. As a result, the French achieved complete surprise and forced Mack’s surrender (2007, 655). Napoleon followed up the capture of Ulm with his greatest victory at Austerlitz on December 2, 1805.

Napoleonic strategies had a profound impact on generations of military commanders, especially in the 19th century. For example, Napoleonic strategy and tactics dominated the military thinking and battlefield decisions of American Civil War officers, as well as those of the legendary Prussian commander Helmuth von Moltke the Elder.

Meritocracy and Compromise: The Marshalate

One reason for the success of France’s army and the expansion of Napoleon’s empire was the blending of the egalitarian and republican spirit of the French Revolution with the traditional privileges and structure of the pre-Revolution Ancien Régime (old order).

Historians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher note that when he ruled as First Consul, Napoleon established the Legion of Honor to recognize excellence in various fields, both civilian and military. This award created a sort of nobility, but one based on merit (2004, 28).

Few areas of Napoleonic France experienced this compromise between old and new as strongly as the military. We’ll take one specific example of this fusion as seen in Napoleon’s senior command structure: the marshalate.

The rank of marshal in the French army was a symbol of the Ancien Régime. Fremont-Barnes and Fisher explain that initially, Napoleon nominated 18 generals as marshals. They were selected based on ability, personal loyalty to Napoleon, or because they represented a political faction Napoleon wished to win (2004, 28).

Fremont-Barnes and Fisher point out that Marshal Davout was the youngest of the original appointments. Marshal Bessières was a nobleman who was also intensely loyal to Napoleon (2004, 29-30). Other marshals, including Lannes and Masséna, came from humble origins.

Napoleon’s insistence on a centralized command, however, created problems for his marshals. For example, his orders prevented marshals from acting independently. In an era before instant communication and battlefields shrouded in smoke, Napoleon’s orders could arrive long after the situation a particular marshal faced had changed.

Napoleon’s Soldiers I: Loyalty

Historians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher point out that a popular saying at the time suggested there was a “marshal’s baton in every [soldier’s] knapsack” (2004, 28). Indeed, several of Napoleon’s marshals began their military careers as ordinary soldiers from the ranks.

These words of encouragement inspired the troops of the Grande Armée, the name associated with Napoleon’s main army on campaign from 1805. As we’ve mentioned, Napoleon was a talented propagandist who helped cultivate his public image and legend. He was also a great motivator of his soldiers. According to historian Andrew Roberts, “Napoleon taught ordinary people that they could make history” (2014, 135).

Napoleon’s soldiers also remained loyal followers because of their attachment to the regiment or unit in which they served. Napoleon recognized the value of legends and stories surrounding particular regiments as tools to inspire troops to fight and maintain discipline.

Nevertheless, the life of a Napoleonic soldier was difficult. For example, soldiers often marched 20 miles (32 km) per day on campaign. According to historian Terry Crowdy, soldiers could march even greater distances if deemed necessary to execute Napoleon’s strategy (2002, 26).

Napoleon’s emphasis on troops foraging for most supplies made sense during the lightning campaigns waged between 1796 and 1805. However, French troops suffered due to poor logistical situations in campaigns after 1805. According to historian Digby Smith, French supply systems broke down due to the increasingly larger armies, longer campaigns, and poor road conditions in places such as Spain and Eastern Europe (2010, 13).

Napoleon’s Soldiers II: Conscription

The bulk of Napoleon’s armies were not made up of volunteers, but of conscripts from across the empire. As we’ve seen with various organizational and tactical innovations of the Napoleonic era, conscription had also been utilized with great success during the French Revolution.

Historian Terry Crowdy notes that Jourdan’s Law of 1798 made all unmarried males aged 20-25 liable for military service. As troop shortages became an issue due to the frequent conflicts of the Napoleonic era, it was common for conscripts to be “borrowed” from the following year’s draft class (2002, 6). As a result, Napoleon’s armies grew younger and more inexperienced, particularly in the campaigns of 1813-1815.

Perhaps the most famous conscript class was the Marie-Louises. Crowdy notes that these teenage recruits derived their nickname from Napoleon’s second wife, Empress Marie-Louise, who signed the conscription decree in Napoleon’s absence during the 1812 Russian campaign (2002, 62).

Conscription was deeply unpopular and became a source of resistance in many territories conquered by France. Many Germans, Italians, Swiss, and others were forced to join units attached to the Grande Armée.

Occasionally, resistance to conscription helped fuel revolts against Napoleonic rule. In 1809-1810, Andreas Hofer led an Austrian-backed peasant revolt in Tyrol against Napoleon’s ally, Bavaria. Hofer’s Tyroleans resented Bavarian taxation and conscription policies, which were designed to support Napoleon against Austria, Tyrol’s traditional ruler. However, historians Gregory Fremont-Barnes and Todd Fisher explain that French and Bavarian forces crushed the revolt, and Hofer was executed in 1810 (2004, 144).

The Decline and Defeat of the Napoleonic Empire

Resistance to conscription proved to be one of many problems Napoleonic France faced by the time the Grande Armée invaded Russia in the summer of 1812.

According to historian Digby Smith, of the roughly 325,000 troops in the Grande Armée at the onset of the disastrous Russian campaign of 1812, only 155,400 were French (2010, 18). The size of non-French troops suggests, in part, the extent to which Napoleon controlled vast swaths of Europe. However, it also highlights the immense losses suffered by French soldiers during the years of bloody battles.

Moreover, many of Napoleon’s best French forces were tied down in Spain and thus unable to join the Russian campaign. Spain indeed was another major factor in Napoleon’s eventual defeat. British forces, along with their Spanish and Portuguese allies, defeated multiple French armies in Spain and Portugal.

Napoleon also failed to appreciate that his enemies could emulate his organization and tactics, thereby turning the tables on the French. Once coalition partners like Austria, Britain, Prussia, and Russia could concentrate their forces, it became difficult for French armies to achieve victory, even with a noted military genius like Napoleon as their commander.

Although defeated in successive campaigns between late 1813 and June 1815, Napoleon’s Grande Armée left a lasting impact on modern militaries worldwide. Indeed, Napoleon’s campaigns are still taught in military academies. Moreover, the permanent corps system remains the main form of military organization in the 21st century.

References and Further Reading

Blanning, T. (2007). The Pursuit of Glory: The Five Revolutions that Made Modern Europe, 1648-1815. Penguin.

Crowdy, T. (2002). French Napoleonic Infantryman, 1803-1815. Osprey.

Fremont-Barnes, G. and T. Fisher. (2004). The Napoleonic Wars: The Rise and Fall of an Empire. Osprey.

Markham, J.D. (2003). Imperial Glory: The Bulletins of Napoleon’s Grande Armée 1805-1814. Greenhill Books.

Riley, J. (2000). Napoleon and the World War of 1813: Lessons in Coalition Warfighting. Cass.

Roberts, A. (2014). Napoleon the Great. Penguin.

Rothenberg, G. E. (2006). The Napoleonic Wars. Collins. (Original work published 1999).

Smith, D. (2010). Armies of 1812: The Grand Armée and the Armies of Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Turkey. Spellmount.