Every culture has an idea of how the ideal man should look. Nowadays, we see beautiful people on social networks, television, catwalks, and walking the red carpet. We tend to see them as an ideal of beauty, creating a standard by which to judge whether or not other people are attractive. It was similar in the past, in each period of our history there existed an idea of how the ideal man should look. In this article, we will explore the idea of the perfect man and male beauty standards as viewed through European history, in ancient Greece and Rome, the Medieval Period, and the Renaissance Era.

The Ideal Man: Youth Equals Beauty

Our story begins in the 6th century BCE in Greece. Attica in particular was a region with strong artistic traditions and excellent sculpture. Here we can find numerous statues of young men in serious, uptight poses nicknamed the “kouros”, meaning “youth”.

The pose of these statues was most likely derived from ancient Egyptian art and provided a clear and easy-to-understand formula for viewers to interpret. They represented a small revolution since before the 6th century BCE, the basic style of art was geometrical, and human figures were mostly painted or depicted in highly stylized, almost abstract, forms. However, these kouros figures demonstrated an idealized version of young men without individual personalities. Their mysterious smile, left foot forward, arms at their sides, and slim bodies were very similar. Rather than depicting individuals, they symbolized a general idea of youthful beauty.

The connection between youth and beauty was important, conditioning the place of the individual in society, who had to live up to the ideal of “arete”, a combination of moral and physical beauty and nobility. Kouros were used as both dedications to the gods and as grave monuments. In time, Greek sculptors abandoned strict Egyptian geometry and began to study human musculature, thus creating a new “ideal”.

Muscles and Brains in the Ideal Man

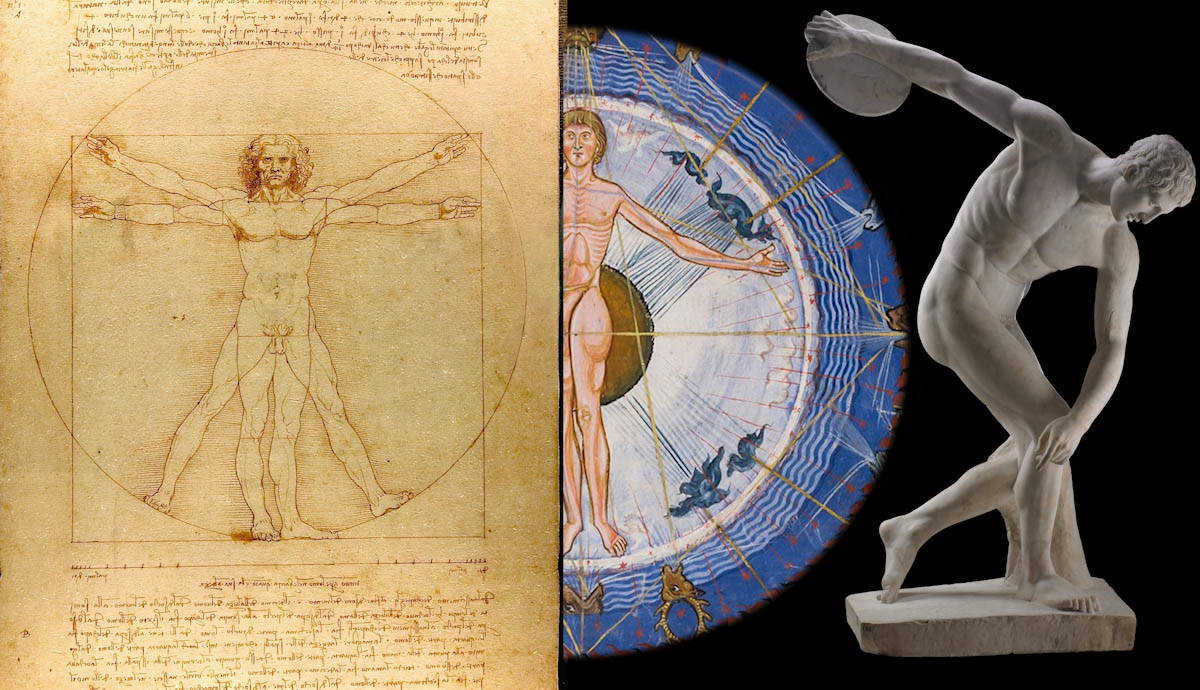

After the transition from more geometric-oriented art toward the naturalistic depiction of the human body, we can observe one of the most famous and precise depictions of the naked male body in ancient art. Statues of athletes and deities even nowadays represent an ideal of the muscular male body. We need to keep in mind that the musculature was not to be overdone, since the ideal was an athletic healthy body. One exception was Heracles (or Hercules), whose strength and life were determined by physical power, thus his over-the-top muscles defined his character. Young men were encouraged to compete in gymnasiums and during sports games, to demonstrate their physical fitness.

Fun fact: If you have ever wondered why penises on athletic Greek bodies are smaller than average, there is a reason for that — a large penis was a symbol of the barbaric wilderness and uncontrollable desires. Since an ideal man was supposed to be beautiful not only from the outside but also from the inside, a need to distinguish oneself as civilized had to be demonstrated on the outside. Knowledge together with a healthy, beautiful body was a symbol of perfection, and nudity on sculptures was not seen as something vulgar or inappropriate — on the contrary, it was viewed as a demonstration of an ideal every man should aim to achieve.

Worldviews began to change especially during the reign of Alexander the Great, when there was a mixture of beauty standards. Later, during the Roman period, the idea of ideal beauty was not the same. With the rise of powerful individuals who were not perfect in the sense of physical beauty, an idea of political power began to emerge. Thus, many portraits from the Roman era were surprisingly realistic, depicting bodily faults, signs of old age, or various “deformities”. Beauty could be “covered” with wealth and power, something that we will see again during the renaissance period.

The Medieval Period: The Divine Body and Cosmic Man

Quite unexpectedly, a new religious movement rose to power during the late years of the Roman Empire: Christianity. With ideas derived from the Middle East and Jewish heritage, these new ideals differed from the ones established by the Classical civilizations of Greece and Rome. The nudity appreciated by both the Greeks and Romans was seen as something shameful that had to be hidden. Of course, there were exceptions — as you can see in depictions of the crucified Christ or John the Baptist, dressed only in a loincloth or animal skin. A naked body itself was not a mark of shame if painted or sculptured in the right context.

The body of Jesus Christ was supposed to be perfect since he was the son of God. Therefore, an ideal man was not a muscular or intellectual man like he was during antiquity, but someone representing spiritual perfection. Jesus Christ was also considered to be born as a perfect man, which is why he was depicted as a full-grown man in numerous Medieval paintings of the Virgin Mary and infant Jesus.

A famous medieval drawing from the mystic Hildegarde of Bingen depicts a man in harmony with the universe. It was not important to show perfect musculature, but perfect symbolism. A man was in the center of the cosmos and his soul was the most important part of his beauty and grace, within a larger cycle of life and the divine plan. Of course, that does not mean that artists during the Medieval Period could not appreciate the beauty of the body, it was just that their focus shifted to the inner human world rather than its external demonstration. People were encouraged to care for their souls more than their bodies, inspired by portraits of Christ and the saints who were seen as ideal men, not because of their outside, but because of their insides. External beauty was still much appreciated, but not so much in visual art.

Vitruvius and Geometry

The scientific observation of the human body and the world around us encouraged renaissance men to resurrect interest in the human body as an example of perfection. One of the greatest polymaths of his time, Leonardo da Vinci, drew a perfect man, nowadays known as the Vitruvian man. A standing nude male with a frowning face, two pairs of arms, and legs are drawn in a perfect circle and a square. It was viewed as an homage to the ancient Roman architect Vitruvius. However, Leonardo’s observations were based more on scientific evidence and his studies of human anatomy. His unique approach combined mathematics and art to demonstrate his understanding of proportion and an attempt to relate man to nature.

His notes, written in mirror writing, state that the drawing was a study of the proportions as described in Vitruvius’s work De Architectura. When we look closer at the text and compare it to Leonardo’s drawing, we can see a few differences in the height of the raised arms and the square and circle centered at the man’s groin. It appears that Leonardo da Vinci improved the model based on his observations, using his incredible skill set.

Male Beauty Standards: Perfection is Hidden in Imperfections

Another famous example of the ideal man from this period is Michelangelo’s David. A tall marble statue (more than five meters/16 feet), of the biblical David shows a young nude man, most likely in preparation for a battle with his giant foe, Goliath. His contrapposto pose, with one leg holding his full weight while the other leg moves slightly forward, gives us an impression of the Classical ideal of beauty. Despite this ideal, the body itself is not perfect when we look at David’s proportions. His head and hands are exaggerated compared to the rest of the body, while the penis is smaller in accordance with the ancient Greek idea of civilization. It could also have been due to David’s historic nickname “strong hand”, or because the viewer had to look at the statue from below.

Overall, the statue has an unusually slender torso, legs, and neck — yet, Michelangelo was a master sculptor and we should not see these disproportions as unintentional. On the contrary, he was aware of them and they played in his favor — after all, David is one of the most recognizable statues in the world to this day. We can see that the ideal man did not need perfect mathematical proportions like the Vitruvian man, but more importantly, his pose, his gesture, and his importance determined whether or not he was considered as an ideal man. This philosophy was also applied to civil portraits at that time, with the ideal shifting from physical or inner beauty to a demonstration of wealth and power.

The Ideal Man: Power and wealth

You are rich and powerful and you are not afraid to show it — this life motto can be applied to nobility during the renaissance era. It was not a shame to demonstrate your power through wealth, and they did not need to idealize their appearance too much in portraits. If we look back, it was a similar philosophy to that held during the Roman Republic, when realistic busts were fashionable.

The powerful middle class began to rise in power and accumulate their wealth, investing in art and talented artists. They were not interested in being portrayed as idealized men, but rather their powerful selves. Their intention was to be individually recognized and not to represent some generalized idea of beauty and perfection. Demonstrations of wealth and power were at the center of painting and brought power to the personalities of their subjects.

The ideal man shifted from a perfect youth to a mature man. This can also be seen outside Italy, as we can observe in the artworks of Jan van Eyck, Hans von Holbein, and Albrecht Dürer. Of course, Jesus Christ or ancient sculptures were still admired and in their view seen as “ideals”, as we can see in early renaissance painting and frescoes with religious scenes, supplemented by patrons who commissioned artwork. Yet, they were aware of their imperfection as well as their power. A portrait was meant to depict the unique appearance of a person with symbols and backgrounds emphasizing a man’s strength. This shift meant that the ideal man was not recognized as a mere symbol, but as an individual who had power in his hands. A focus on inner or outer beauty was overshadowed by individual strength.

To summarize the ideal man concept, we can apply these ideas to current society. How would an ideal man from the periods mentioned above look on modern social media? In the first case, he would be working out in a gym while reading Plato, while the Medieval ideal would be a spiritual man trying to connect with his inner beauty and self (and ideally be slim), and the Renaissance man would show his wealth and success. In time, the idea of a man was individualized and hard to keep track of, but I believe that the ideals of Classical Greece, Medieval spirituality, and Renaissance naturalism are up to this day three cornerstones that define the male ideal.

References and Further Reading:

Picón, Carlos A. 2007. Art of the Classical World in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: Greece, Cyprus, Etruria, Rome. no. 67, pp. 70–71, 419, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Zanker, Paul. 2016. Roman Portraits: Sculptures in Stone and Bronze in the Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 3, fig. 3, New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

https://www.namuseum.gr/en/collections/

http://www.hildegard-society.org/p/liber-divinorum-operum.html

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/ropo/hd_ropo.htm

https://www.gallerieaccademia.it/en/node/1582

National Portrait Gallery Learning: In focus: Hans Holbein the Younger. Available: https://www.npg.org.uk/assets/files/pdf/learning/NPG_HansHobein_09.pdf

Jack Ford: Divine Love in the Medieval Cosmos

The Cosmologies of Hildegard of Bingen and Hermann of Carintiha https://cjh.uchicago.edu/issues/spring17/8.5.pdf