The Gutenberg Press revolutionized how information was produced and disseminated, marking a milestone in the history of book production in Europe. Produced in the mid-15th century by Johannes Gutenberg in Germany, this innovative press combined the movable metal type with a screw press mechanism, making it possible to print books. This offered an alternative to manuscript-making, as before this, book-making was a laborious and slow process that was usually reserved for the specialized monastic scriptoria. This invention fueled major events such as the Protestant Reformation and the Scientific Revolution.

Europe on the Eve of the Gutenberg Printing Press

Europe, before Johannes Gutenberg’s invention, was a place eager for advancement yet limited by resources, technologies, and accessibility. Even though the culture was rich and the appetite for reading existed, books and manuscripts, in general, were luxury objects as they required the work of several people over a long period of time before they could be completed and used by readers. This limited accessibility meant that literacy was also localized and reserved for certain social groups, such as the clergy, the intellectuals, and those who could afford to learn and buy such items.

The most common item used for knowledge communication in this period before the invention of the press was the manuscript. Since the Middle Ages, when it came to manuscript production the monasteries were the main centers which were in charge of the production of manuscripts. The monastic scriptoria were spaces designated specifically for the purpose of copying texts, thus circulating knowledge inside the monastery and outside of it as well. Another factor that encouraged the expansion of knowledge and prompted a need for easier transmission was the university as an institution. Universities rose during the 12th and 13th centuries in important cities in Europe, and by the 16th century, most regions of Europe had at least one university. This steady growth of universities created an increased demand and appetite for books.

Who Was Johannes Gutenberg?

Johannes Gutenberg (c. 1398-1468) was born in Mainz in modern-day Germany and was the son of a well-to-do merchant. Unfortunately, not much information is available regarding his early life and youth, but he most likely began an apprenticeship in metalworking and goldsmithing as a young man. This would explain his great familiarity with this type of work, a familiarity which contributed to the invention of the printing press. Around 1440, Gutenberg began developing prototypes for the printing press. The press he was trying to complete didn’t succeed from the prototypes but needed several years of work until a functional prototype could be completed. This lengthy process meant that Gutenberg ended up investing most of his personal funds in this project.

When word of his printing press prototype began to spread, the businessman Johan Fust was interested in investing in Gutenberg in hopes of getting a high return from this once the press was completed. Gutenberg and Fust planned to complete the press and then print books in a faster and cheaper way, essentially gaining a monopoly over the manuscript market. The aim of this was to use this monopoly to shift the buyers towards printed books as they were more affordable and faster to create. This dream was achieved in 1455 with the printing of the Gutenberg Bible, probably the most well-known publication of the Gutenberg Press. However, due to delays in finishing the press, Gutenberg lost his rights to the press over Fust, and the business went on without him.

Printing Press Before Gutenberg

Before the Gutenberg Press and beyond monastic scriptoria, other printing techniques were developed in Europe and outside of it. To better understand the world in which the Gutenberg Press came to be, a summary of the printing techniques existing up to the 15th century is necessary. In Europe, printing as an idea appeared during the 14th century when block printing was introduced from East Asia. This technique functioned by sculpting text on wooden blocks, dipping the blocks in ink, and then pressing them on paper. This was similar to a technique used by the Chinese since the 6th century. In East Asia, the moveable type press appeared around the 11th century and used ceramic elements that could be moved around to print the desired text. Despite its similarity to the Gutenberg Press, this invention didn’t have a lasting impact.

The Islamic world didn’t have a type of printing press. A popular method of imprinting something on paper was stenciling. However, this was used mainly for decoration purposes and not for text. From what can be gathered, in the eastern part of the world, Chinese block printing was the most prominent printing technique. Block printing had been popularized in Central Asia as well in India where it was in use much earlier than in Europe.

How Did the Gutenberg Press Work?

The Gutenberg Press functioned with the help of individual letters made out of metal, such as durable alloys made out of lead, tin, and antimony. This ensured that each letter was reusable and moveable, making it possible for them to be arranged in any desired order to create a text. Once the necessary number of letters was selected, the next step was typesetting. During this step, a compositor (someone who was in charge of the process of arranging letters) made sure that the metal letters were placed in a frame that would correspond to the desired page layout. One of their most important tasks was to make sure that the text was placed in the correct orientation and that the letters were aligned and had the right spacing between lines. Once these two first crucial steps were in place, the Gutenberg press could be used.

This press had a screw press which was similar to those used in the process of making wine. The press was designed to include a flat plate where the frame with the page layout was placed after it was inked. The inking was done by applying a specially formulated oil-based ink with the help of leather-covered ink balls. The final stages included pressing the inked type on the sheets of dampened paper while the flat plate was pressed using a screw system. After the paper was printed, the operator unscrewed the plate, removed the sheets, and hung them to dry.

Operating a Printing Workshop

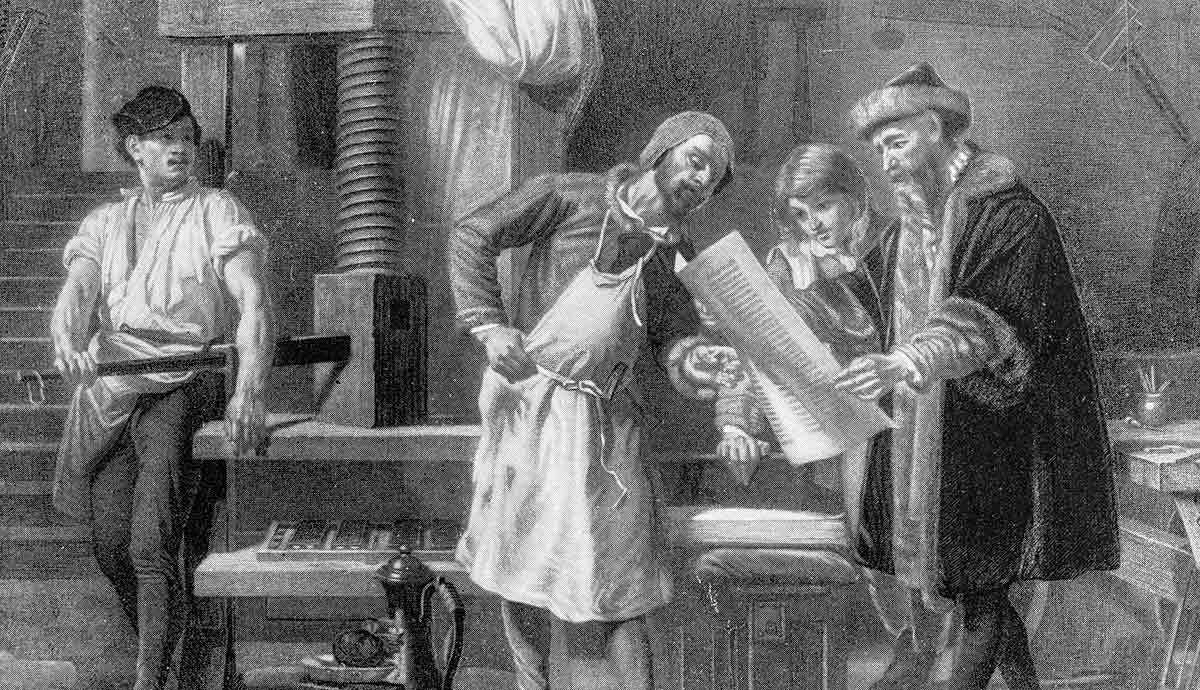

To operate a printing workshop was no simple matter, as the process of printing, although quicker than manuscript making, was still a complex one. To run a workshop, one would need from 5 to 20 people to operate the printing press and ensure a smooth production. The first and most important position within a printing workshop would be that of the master printer, who played the role of the manager. Most of the time, the master printer himself was familiar with the printing press and was able to manage the other workers and solve any problems that may have arisen with the press. Besides him, compositors were responsible for arranging the letters on a page, and press operators who mounted the pages on the printing press were essential in this process. For example, for a fast operation of the press, at least two operators were needed as one would ink the type while the other operated the screw mechanism.

Ink makers and papermakers were essential to the crafts. They could’ve been external collaborators with whom the workshop had contracted. The ink makers were crucial to preparing the special oil-based ink for printing, while the papermakers were the lifeline of the printing because they were the ones who supplied paper and ensured its quality. Some other roles within the workshop included proofreaders who would check for errors and inconsistencies, but also apprentices or manual laborers to help with tasks such as cleaning the press or carrying the materials.

Improvements to the Gutenberg Press Model

The Gutenberg Press was a successful model for the printing press and changed how books were created. Despite this, it wasn’t a perfect model. This is why those who entered the printing business looked for ways to perfect the shortcomings of the Gutenberg Press and improve the speed and efficiency of printing. Some of the improvements of the press include a betterment of the screw mechanism, which allowed for a smoother and more consistent operation. The flat plate was also made more stable and capable of applying more pressure to the paper. During the 17th century, some printing presses added sliding carriages which were used to reposition the type and the paper faster in between print cycles.

The production of ink and paper also developed further, with makers now being able to provide ink with better color vibrancy and more consistent pigments. Paper was improved by the adoption of rag-based paper that provided smoother surfaces to capture finer details in print. The general goal of the printing press during the early modern period was to increase automation. This is visible especially in the Dutch Press which developed a counterbalanced lever system that made printing easier and faster, reducing the force required to operate the press. Standardized typefaces and the introduction of more durable metal types encouraged the longevity of the press and made it possible for printmakers to buy used metal types, which were still in good shape due to this improved formula.

The Afterlife of the Gutenberg Press

The Gutenberg Press had both an immediate and a long-term impact on the dissemination of knowledge and the evolution of books as objects. Books became more affordable and transformed from a luxury item to an affordable one. This led to a dramatic increase in literacy across Europe. The information circulated more freely and wasn’t restricted to certain circles. Anyone could print their own work and buy a book. As books were produced in greater numbers than before, they were standardized due to the formats that worked best with the printing press.

All of these factors contributed to the information revolution that occurred in Europe during the 16th and 17th centuries where the ideas of Martin Luther or Galileo Galilei could reach all corners of Europe. Through books, people engaged with ideas, responded to them, and generated new ideas. This also meant that the publishing industry was on the rise, as the popularity of books meant great returns for book publishers. More and more people were joining this craft in hopes of running a successful business.

The afterlife of the Gutenberg Press can be seen in the mechanization of the printing press during the 18th and 19th centuries. The manual press was gradually replaced by a steam-powered press that could produce thousands of pages every few hours. The rotary and linotype presses, which appeared during the late 19th century, increased the automation of the press, creating an even greater output of pages.

Despite the Gutenberg Press being a European phenomenon, the printing revolution of the early modern period must be seen in a global context. The early Asian models of the printing press, together with the colonial expansion of European powers, made the printing press and the production of books readily available around the world. From this perspective, it comes as no surprise why the Gutenberg Press is credited as the catalyst for the “Information Age” and why the Gutenberg Bible is such a precious milestone in our collective history of the book.