American artist Jasper Johns has left no medium untouched throughout his pursuit of painterly perfection. From subverting Abstract Expressionism to pioneering a Neo-Dada resurgence in New York City, he’s now best recognized for his depictions of ordinary household objects like the U.S. flag. His brilliant biography further highlights this illustrious career.

Jasper Johns’s Early Years

Jasper Johns experienced a turbulent upbringing. Born in Georgia in 1930, his parents divorced after his birth, bouncing him from one relative to another. He spent his childhood with his paternal grandparents in South Carolina, where he took interest in portraiture displayed throughout the house. From then on, Johns knew he wanted to be an artist, not quite anticipating what this career choice entailed. While attending The University Of South Carolina, his teachers recommended he move to New York to pursue art, which he did per their instruction in 1948. Parsons School of Design proved an educational mismatch for the misguided Johns, however, causing him to drop out within a semester. Susceptible to being drafted into the Korean War, he left for Sendai, Japan in 1951, where Johns stayed stationed until his 1953 honorable discharge. Little did he know his entire life would change when he returned to New York.

When Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg Fell In Love

By 1954, Jasper Johns worked full-time at Marboro Books, a discount chain store selling overstocked editions. There, he also met a fellow force-of-nature nearly five years his senior, Robert Rauschenberg. The artist invited Johns to help him decorate store displays for Bonwit Teller and the two quickly fell in love. Within a year, they rented studios in the same Manhattan building on Pearl Street, friendly neighbors to emerging performance artist Rachel Rosenthal. Through Rauschenberg, Johns also experienced an unofficial introduction into the contemporary art world, to which he felt comparatively immature. In fact, after meeting peers John Cage and Merce Cunningham, Johns felt even more intimidated by the tenacious trio. “They were more experienced and strongly motivated to do what they were doing,” he later remarked in a NY Times interview. “And I benefited from that. That reinforced a kind of forward movement.” Johns soon converted his fear into determination.

His First Flag

Pearl Street transformed into an epicenter of creativity thanks to its new residents. Neo-Dadaism, a style merging high art with everyday life, also spread like wildfire amongst New York’s most impressionable minds. Jasper Johns absorbed these fresh surroundings, beginning his artistic journey in 1954 after he had dreamt of a colossal American flag. He created his legendary Flag (1954) the next day, constructed using an ancient encaustic method of dripping hot beeswax, tree sap, and pigment on canvas. As opposed to an opaque concept, Johns approached his subject as a singular object, not only a symbol. Depicting a motif ubiquitous throughout American consumerism, however, Flag nonetheless raised a semiotic conundrum: is it a flag, a painting, or both? Notwithstanding meta-philosophy, the painting’s meaning also varied amongst viewers, who interpreted anything from patriotism to oppression. Johns intentionally eschewed set connotations to conjure binaries about “things which are seen and not looked at.”

The American Artist’s Rise To Fame

His objectives evolved throughout the following year. In 1955, Jasper Johns produced Target With Four Faces, a crossover between a canvas and a sculpture. Here, encaustic-dipped newspaper layered creating visceral visual effects, bound below four plastered renderings of a female’s lower face. Johns deliberately removed his model’s eyes to ensure audiences would be forced to confront the ambiguous relationship between Target’s painting and three-dimensional elements, asserting its objecthood proudly. Exhibited during a 1957 Jewish Museum group show, this eyebrow-raising artwork ultimately caught Leo Castelli’s attention. The young and emboldened entrepreneur had just opened a gallery of his own. In March that same year, Castelli’s visit to Rauschenberg’s studio quickly derailed when he noticed another growing collection. “When we went down, I was confronted with that miraculous array of unprecedented images,” Castelli recalled. “Something one could not imagine, new and out of the blue.” He offered Johns a solo-show on the spot.

Solo-Show At The Leo Castelli Gallery

Jasper Johns’s first 1958 solo-show proved a smashing success. Though Castelli took a risk by exhibiting the inexperienced artist, his gamble paid off ad infinitum, catapulting both him and Johns to fame. Within Castelli’s intimate gallery hung symbolic impastos like Flag, Target, and the painter’s newest edition, Tango (1956), made in solid gray graphite on paper. Critics showered Johns with surprisingly positive reviews, signaling a monumental turning point for modern art. Abstract Expressionism had been made near obsolete. In its place emerged gutsy artists like Johns and Rauschenberg, a generation who dared to defy boundaries beyond a simple surface level. Writing for the New Yorker in 1980, Calvin Thompkins summarized this dramatic occasion best, claiming Johns “hit the art world like a meteor.” Many, like MoMA’s first director Alfred Barr, took note of his reverberations. The prestigious figure attended Johns’ opening himself and purchased four paintings for the museum’s collection.

Why Did Jasper Johns And Robert Rauschenberg Break Up?

As polychromatic Pop Art bloomed during the early 1960s, Jasper Johns beelined for an opposite palette. Many attribute this somber color shift to his deteriorating relationship with Rauschenberg, with whom he officially cut ties in 1961, purchasing another studio in South Carolina. As opposed to Johns’s cheerful canvases like False Start (1959) and Painting With Two Balls (1960), his later work reflected this emotional chaos through dismal hues of black, grey, and white. Painting Bitten By A Man (1961), for instance, is a tiny artwork rumored to contain teeth marks. A muted composition featuring a compass-drawn circle in its corner, Periscope (1962) also symbolizes his personal grief, nodding to poet Hart Crane, who frequently ruminated on love and loss. Johns also explored more sculptural elements in Painted Bronze (1960), two beer cans painted in sparkling gold. His adventure representing mass-produced goods would set a larger stage of exploration for his future.

Mature Period

The late 1960s presented unique opportunities for Jasper Johns to expand his multi-disciplinary repertoire. Before long, he silkscreened works like According To What (1964), incorporating newspaper clippings discussing Russia’s Kremlin. Unlike peers using this duplication method, however, Johns painted around his headlines, eager to leave his own original mark. By 1968, he began his thirteen-year tenure as Artistic Advisor to Merce Cunningham and his co-owned Dance Company, where he designed the set decor for a Walkaround Time production. Modeled after his idol Marcel Duchamp’s The Large Glass (1915), Johns stenciled imagery from Duchamp’s work, like “The Seven Sisters,” onto vinyl sheeting. He then stretched these over seven metal cube frames, which were integrated into Cunningham’s choreographed routine. Dancers pranced on stage clutching his ready-made cubes in homage to avant-garde’s forefather. Unfortunately, a sudden fire then engulfed John’s studio back home in South Carolina, forcing him to rethink his own path.

Splitting his time between St. Martin and New York, Johns employed more abstract methods during the 1970s. A few years earlier, he had joined forces with Tatyana Grosman at Universal Limited Art Editions, where he became first to use its hand-fed offset lithographic press in 1971. This resulted in Decoy, a mysterious print containing seemingly nonsensical amalgamations of past motifs. By 1975, he experimented further by covering his nude body in baby oil, laying across a sheet of paper, and scattering charcoal on its remnants. Skin (1975) is quite literally a phantom-like imprint of Johns’s astounding artistic presence. Seen in Savarin (1977), the American artist also introduced cross-hatching into his paintings, this time as a self-referential backdrop to an earlier bronze sculpture. Johns created this monstrous lithograph as a poster for his upcoming 1977 Whitney Museum retrospective, which encompassed a whopping 200 paintings, sculptures, and drawings from 1955 onward.

Exploration Of Darker Themes

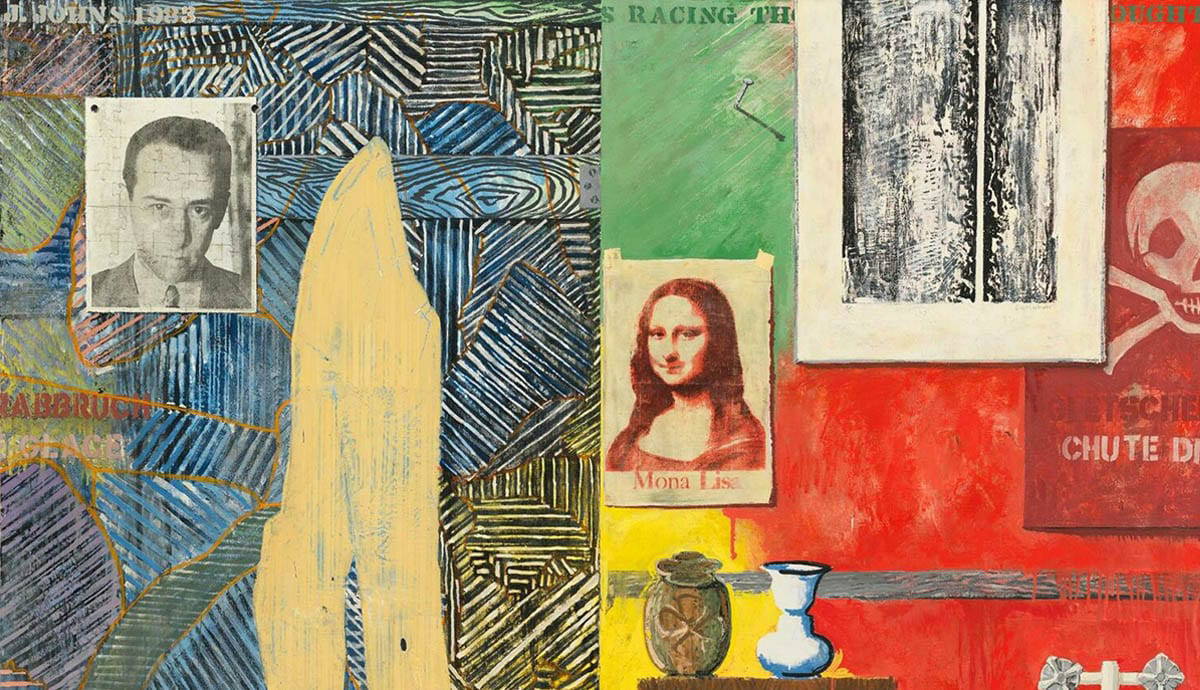

His themes turned broodier during the 1980s. While Jasper Johns once concerned himself with universal imagery or shifting meanings between viewers, he gradually narrowed his focus to emphasize art historical symbols and personal possessions. Usuyuki (1981) demonstrates an improved crosshatch technique alongside advancements in printmaking, using twelve screens to produce several layers of soft gradience. While its title translated in Japanese to “light snow,” cross-hatching, as he put it, “had all the qualities that interest [him] – literalness, repetitiveness, an obsessive quality, order with dumbness, and the possibility of complete lack of meaning.” By comparison, however, his series The Seasons (1987) reads as thematically dense, an intimate glance at how our bodies age through the seasons. Narrating his career stages, a scaled-down version of Johns’s shadow sat beside symbols like the Mona Lisa, the American flag, and an homage to Pablo Picasso. Masterpieces like these rarefied as another decade approached.

Preserving his market value, Johns decreased his artistic output to roughly five paintings per year beginning in the 1990s. He then joined the National Academy of Design in 1990 as an Associate member, and by 1994, he had been elected a full Academician. Nearing sixty, the American artist had since become disgruntled with increasingly obscure interpretations of his art, resolving to eliminate any future motifs necessitating prior knowledge. In 1996, he celebrated a sprawling retrospective at MoMA, surveying 200+ paintings beginning in his early Flag era. Johns also widened his social circles a bit, considering a visit with Nan Rosenthal, senior consultant at the MET, inspired him to title his Catenary (1999). Loose, long, and curvilinear brushstrokes congealed a multi-colored underlayer, affixing found objects like pine slat. Even renouncing symbolism for abstraction, Johns continued to extend his allegorical references into new modes of creative expression.

Later Years

He continued these experiments into the 2000s. Johns produced his limited-edition linocut titled Sun On Six (2000), rehashing motifs from his earlier Device (1962). This time, his setting sun has been obscured to almost abstract, a black-and-white byproduct of blurred brilliance. By 2005, he temporarily abandoned figurative painting, assembling encaustic wood panels like Beckett. Its textured coating shaped a slimy, scale-like consistency, nearly too tempting to not reach out and touch. Years later, he migrated to sculpture again, unveiling Fragment Of A Letter (2009). Serving as a visual puzzle, his double-sided relief contained allegorical fragments from a letter Vincent Van Gogh once wrote on one side. On the other, the same note appeared translated into braille, challenging expected perceptions of Johns’s creative handprint. His career then came full circle in 2010 when Flag sold for a whopping $110 million, advanced by none other than Jean-Christophe Castelli, son of Leo Castelli.

Jasper Johns’ Current Legacy

Since then, Jasper Johns moved to a suburban home in Connecticut, where he still lives and works today. The American artist stirred headlines in 2013 when he charged former studio assistant, James Meyer, with theft of nearly seven-million-dollars-worth of artwork. (He was later convicted, then sentenced to eighteen months.) In 2019, Johns celebrated a well-received solo show at New York’s Matthew Marks Gallery, Recent Paintings And Works On Paper. Spanning recent works from 2014 to 2018, his meditation on mortality ranged from linoleum prints to paintings and a tiny etching executed on confetti paper. Among reconceptions of old methods also emerged an endearing new motif: a withering skeleton sporting a top hat, occasionally balancing a cane. In Untitled (2018), for example, Johns alludes to another ghostly shadow from his earlier Seasons series, his fleshed-out figure now locking eyes with its viewers. Even at ninety, he continues to conjure his raw emotional urgency.

Now, Johns is acclaimed for his relentless passion, persistent as ever while sporting childlike ambition. Though his painting production has greatly declined, it’s impossible to deny the laudable legacy he leaves behind. He’s permanently obscured the line between high art and contemporary culture, inspiring everyone from Pop legend Andy Warhol to American jeweler William Harper. Luckily, even long after his death, a residency established at his Connecticut home will continue to foster safe spaces for innovators of all kinds, whether sculptors, poets, or dancers. Selected forerunners here treasure opportunities to learn under the guidance of one of America’s most dynamic living artists. By dismantling an entire NY hierarchy with his shift toward figurative painting, Jasper Johns trailblazed modernism boldly as an openly queer man, true to himself during an era where the spotlight proved even more grueling. It suffices to say he’s since altered our perception of visual art forever.