In the last days of July 1830, a series of repressive ordinances issued by King Charles X provoked widespread protests. Led by liberals and moderates, the demonstrations in Paris soon turned into a full-fledged revolution: the Second French Revolution. After three days of street fighting between the armed protestors and the police, Charles X abdicated the throne. He was succeeded by Louis-Philippe, the Duc d’Orléans, supported by the middle-class moderates and constitutional monarchists. Known as the July Monarchy, Louis-Philippe’s reign marked the rise of the bourgeoisie but failed to bring stability to the country.

The Historical Background: The Bourbon Restoration

On March 30, 1814, the forces of the anti-French coalition—Austria, Russia, Prussia, and Great Britain—reached the outskirts of Paris. On April 6, Napoleon Bonaparte, the Emperor of the French, abdicated and was sent into exile on the island of Elba off the west coast of Italy.

By then, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, the president of France’s provisional government, had already begun negotiating with Louis XVIII, one of the brothers of Louis XVI, the king guillotined in 1793 during the French Revolution. Restored to the French throne, Louis XVIII granted the Charter of 1814.

The document, known as la Charte octroyée (“the charter granted”) to emphasize that it was granted by the monarch, established a constitutional monarchy after the English model. The new constitution introduced a bicameral parliamentary system, guaranteed civil liberties and religious toleration (although Catholicism was recognized as the state religion), and gave the king the power to appoint ministers, convene or dissolve the Chamber of Deputies, and sanction any laws passed in the two chambers.

The four European powers—Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Great Britain—that led the anti-Napoleon alliance supported the Bourbon Restoration in France, hoping it would restore stability to the country and prevent future revolutionary upheavals from threatening the new European order established at the Congress of Vienna. Organized to dismantle the vast Napoleonic empire, the meeting in Vienna aimed to secure a balance of power in the continent (the so-called “Concert of Europe”) by preserving territorial integrity and the principle of legitimacy. At the same time, the congress sought to limit the impact of the French Revolution across Europe.

In March 1815, the stability of the newly established Bourbon rule was immediately threatened by Napoleon’s attempt to seize power after escaping from Elba. The so-called Hundred Days, however, ended with the former emperor’s final defeat at the Battle of Waterloo and the return of Louis XVIII to France on July 8, 1815.

The Rise of the “Ultras”

In the following decade, Louis XVIII sought to establish a moderate rule, trying to reconcile the democratic ideals of the 1789 Revolution with France’s first attempt at a constitutional monarchy. His efforts, however, were largely thwarted by the rise of the ultras (ultraroyalistes or ultra-royalists), the extreme right wing of the royalist movement, which supported the interests of the landowners and former émigrés and aimed to eradicate the legacy of the French Revolution.

First emerging in 1815, the ultras eventually gained control of the Chamber of Deputies in 1820, when a fanatic Bonapartist assassinated Charles-Ferdinand de Bourbon, the king’s nephew, in a failed effort to end the Bourbon dynasty (Charles-Ferdinand’s wife had a son seven months after her husband’s death). After Louis XVIII dismissed the ministry of the moderate Élie Decazes and called for general elections, the ultras secured a majority in the Chamber, and one of their leaders, Joseph de Villèle, was tasked with forming the new cabinet.

Alarmed by the ultras’ victory, the Charbonnerie, a secret society inspired by the Italian Carboneria, planned an unsuccessful insurrection in 1822. Meanwhile, the ultras-controlled government began pursuing a more aggressive foreign policy. In 1820, a revolt in Spain had forced King Ferdinand VII to grant a constitution. To prevent the unrest from spreading across the continent, the European powers backed France’s intervention to restore Ferdinand VII to the throne.

The successful military campaign in Spain consolidated the ultras’ power in France, and the 1824 elections saw the ultra-royalists secure their hold in the Chamber of Deputies. Then, in September of the same year, a leader of the ultras, Charles-Philippe, comte d’Artois, succeeded Louis XVIII on the throne, becoming King Charles X. The ultras’ control over France seemed complete.

Setting the Stage: The Reign of Charles X

After the 1789 storming of the Bastille, the comte d’Artois was the first member of the French royal family to go into exile. He spent the following years travelling to Austria, Russia, Prussia, and England before organizing an unsuccessful royalist uprising in the Vendée region in 1814. In the same year, he returned to France and quickly emerged as a leading figure in the ultras movement.

Upon inheriting the throne as Charles X, Charles-Philippe set out to implement the reactionary policies supported by the ultras. Backed by the monarch, the Villèle ministry compensated the émigrés (aristocratic landowners who fled France after 1789) for the loss of their lands confiscated by the revolutionary government. To cover the costs of the compensation (about 1 billion francs), the cabinet arbitrarily lowered the interest rates of the government bonds, causing widespread discontent among the upper-middle-class bondholders.

In the first years of his reign, Charles X also backed a campaign for Catholic revival to restore the role of the Roman Catholic Church, whose authority had been challenged in the previous decades by the Enlightenment movement and the Revolution. At the same time, the king rejected the constitutional monarchy model, seeking to reassert the principle of divine right—the political doctrine that claims monarchs derive their authority directly from God.

As new laws tightened the censorship of the press, targeting liberal publishers, public discontent began to rise. In the face of spreading opposition, in 1827, Villèle decided to call for general elections, hoping to strengthen the ultras’ hold on the Chamber. Despite holding off the official announcement until November 5 to prevent the opposition from organizing their campaign, the November 17 and 24 elections resulted in a defeat for Villèle.

With the assistance of the committee Aide-toi, le ciel t’aidera (“God helps those who help themselves”), led by François Guizot, the liberal candidates successfully managed to counteract the ministry’s machinations to keep them off the ballot. Charles X responded to Villèle’s defeat by appointing the more moderate vicomte de Martignac as the head of the cabinet.

However, Martignac’s compromise policies soon displeased the king, who dismissed and replaced him with the unpopular reactionary prince de Polignac.

The July Ordinances

The Polignac cabinet, composed of several members of the most extreme factions of the ultras, caused further divisions in the already polarized political landscape. In Paris, the republican groups began to mobilize, and the liberal upper middle class rallied behind a new opposition newspaper, le National, sponsored by Jacques Lafitte, the governor of the Bank of France. The French bourgeoisie was especially dissatisfied with the government’s efforts to defend the interests of the landed aristocracy and restore its social predominance.

In March 1830, tensions between the minority and the government increased as Charles X gave a speech announcing his intention to limit the legislative powers of the Chamber of Deputies. On March 15, a committee of 221 opposition deputies presented a statement condemning the cabinet’s reactionary policies. After reminding the monarch that “the participation of the country in the discussion of public affairs” was defended as a right by the 1814 Charter, the deputies argued:

“An unwarranted mistrust of the feelings and thoughts of France is today the fundamental attitude of the Administration. Your people are distressed by this because it is an affront to them; they are worried by it because it is a threat to their liberties.”

Charles X responded to the address by dissolving the Chamber and calling for a general election. While the king and the ultras hoped that the conquest of Algiers in North Africa by the French expeditionary forces might shape the outcome of the election in their favor, the opposition secured 274 seats, almost 100 more than the ministry.

Despite the unfavorable outcome of the election, Charles did not replace Polignac with a more moderate statesman. On July 26, 1830, the Moniteur universel, the official newspaper of the French government, published a report announcing a series of repressive measures. Known as the July Ordinances, these decrees dissolved the newly elected Chamber of Deputies, introduced a rigorous censorship of the press, called for new elections, and restricted the right to vote to favor the interests of the landed aristocracy.

The July Days: Les Trois Glorieuses

Among the first to react to the unpopular July Ordinances were the liberal and moderate journalists. From the pages of le National, Adolphe Thiers accused the king and the ministry of planning a coup d’état and protested the decision to dismiss the lawfully elected Chamber. Failing to realize the brewing discontent following the July 26 measures had laid the groundwork for violent protest, Charles X left Paris without making any contingency plans.

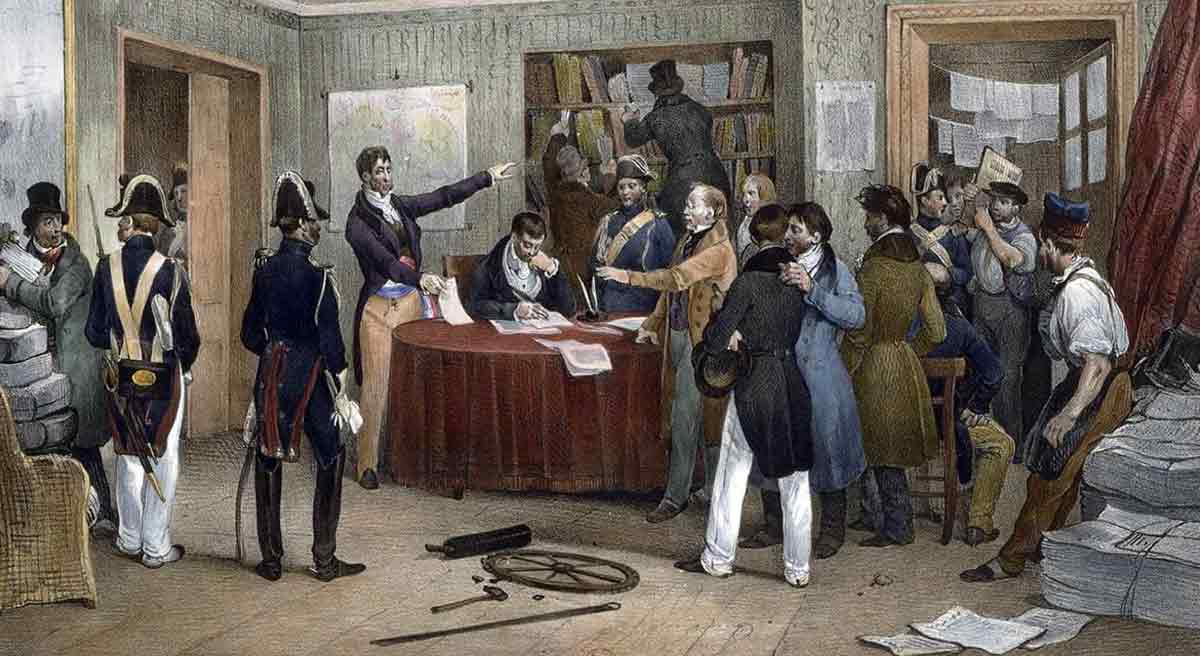

On July 27, when the police intervened to prevent the staff of le National, le Globe, and le Temps (all leading opposition newspapers) from distributing copies of their morning editions, the first uprisings broke out in the French capital.

On the night between July 27 and 28, the protests turned into a full-fledged revolution, with people building barricades in the streets to fight the 12,000 soldiers led by the unpopular Marshal Marmont. The violent confrontation between armed revolutionaries and soldiers went on for three days, known in France as les Trois Glorieuses, or July Days. Famously depicted by French artist Eugène Delacroix in his painting Liberty Leading the People, the Second French Revolution is also featured in Victor Hugo’s novel Les Misérables, set in the years leading to the July Days.

On July 29, Marmont sent an urgent missive to Charles X to urge him to act: “This is no longer a riot, this is a revolution. It is urgent that Your Majesty decide on the means of pacification. The honor of his crown can still be saved; tomorrow perhaps it will be too late.” The Marshal’s sense of urgency was not without cause. By July 29, many soldiers had already begun to fraternize with the revolutionaries. Marmont, left with only a fraction of his forces, was forced to retreat. Soon afterward, the insurgents broke into the Bourbon Palace.

Charles X agreed to dismiss Polignac only on July 30, but it was too little, too late. From their stronghold at the Hôtel de Ville, the republicans created a municipal commission, while the liberal faction, headed by Adolphe Thiers, called for Louis-Philippe, duc d’Orléans, to replace Charles X as king. Initially reluctant, Louis-Philippe eventually accepted Thiers’ offer and met with the republicans at the Hôtel de Ville, winning the support of General Lafayette, a leading figure in the First French Revolution. The July Days were over.

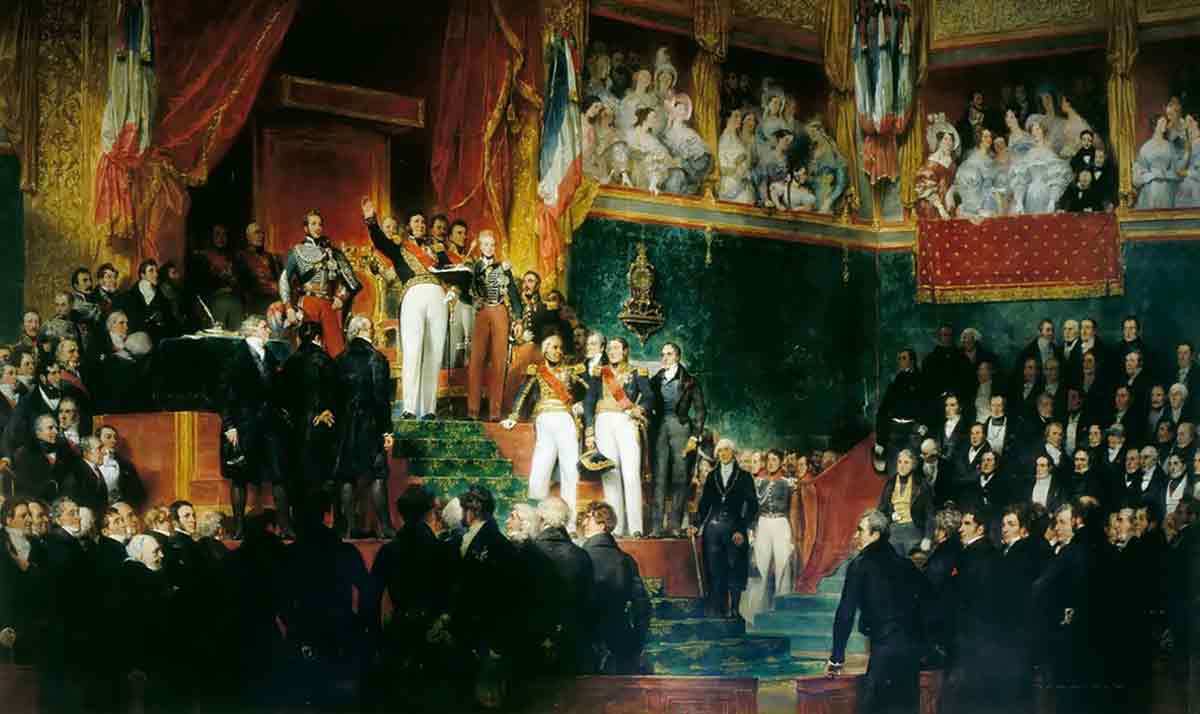

King Charles X abdicated on August 2. On August 9, 1830, the parliament declared Louis-Philippe “king of the French by the grace of God and the will of the nation.”

The Aftermath of the Second French Revolution: The July Monarchy

Louis-Philippe’s reign, known as the July Monarchy, marked a shift in the French social landscape, with the wealthy bourgeoisie replacing the landed aristocracy as the country’s most influential social force. Indeed, the Second French Revolution led to a triumph of the liberal bourgeoisie, and Louis-Philippe’s rule mainly rested on the support of liberal bankers and industrialists.

Meanwhile, the revised 1830 Charter introduced a more defined constitutional monarchy in France. The new document rejected the principle of divine right, abolished censorship of the press, and extended suffrage to include all males who paid 200 francs in direct taxes. The Charter also restored the tricolor as the national flag and no longer referred to Catholicism as the state religion; instead, it defined it as the faith “of the majority of the French.”

Despite the widespread support of the liberal bourgeoisie, Louis-Philippe, nicknamed the “Citizen King,” had to navigate a complex political landscape during his reign. Opposed by the ultras on the right and republicans and socialists on the left, the monarch survived several assassination attempts, including the 1835 plot orchestrated by Giuseppe Maria Fieschi.

Faced with the rapid changes brought by industrialization and urbanization, the July Monarchy’s attempt to pursue a juste milieu (middle way) ultimately failed. As social unrest and the dissatisfaction of the working class with the status quo grew in the late 1840s, Louis-Philippe abdicated his throne on February 24, 1848, following the February Revolution, an uprising born out of the revolutionary movement sweeping across Europe in 1848. The July Monarchy was replaced with the Second Republic.