When the Neo-Marxist philosopher Jürgen Habermas and Catholic cardinal Joseph Ratzinger debated the place of religion in the public sphere, they agreed that faith and reason can illuminate each other despite their long-standing tension.

During this debate Habermas, an atheist, asked secular citizens of liberal democracies to put aside post-metaphysical pre-suppositions to better understand “religious convictions.” This article outlines Habermas’ rationale for wanting the religious voice in the public sphere.

What Is the Public Sphere According to Habermas?

Coined by Habermas, the term “public sphere” refers to the social space where citizens “meet” to discuss issues that are of mutual concern. It is the place for forming public opinions on topics of general interest and with political implications. Regulated by journalistic norms and practice, public sphere discussions can influence local government and shape policy and, as we see more and more, they have tremendous power to make or break the reputations and standing of individuals, companies, and groups.

Whether digital, in print, or otherwise, discourses in the public sphere are provoked by social injustices—wars, racism, homelessness, immigration, etc. A consensus (on how to approach these matters and what change is needed) is achieved when the majority accepts one view over another. Having had the opportunity to participate in the debate, those in the minority are obliged to concede to the majority view.

Individuals come into the public sphere by choosing to put aside their personal agendas. They form a public with other individuals, their fellow citizens. Although most try to enforce their own ideologies when taking part in public sphere dialogue, the hope is that with the conscious disengagement from individualism, a disengagement that is considered the ideal state for contributors who therefore work to achieve it, participants can be characterized as open-minded and inclusive.

Consequently, the core values of the public sphere mirror those of the liberal democratic state which, by opening its voting system to all, is similarly “governed by the people.”

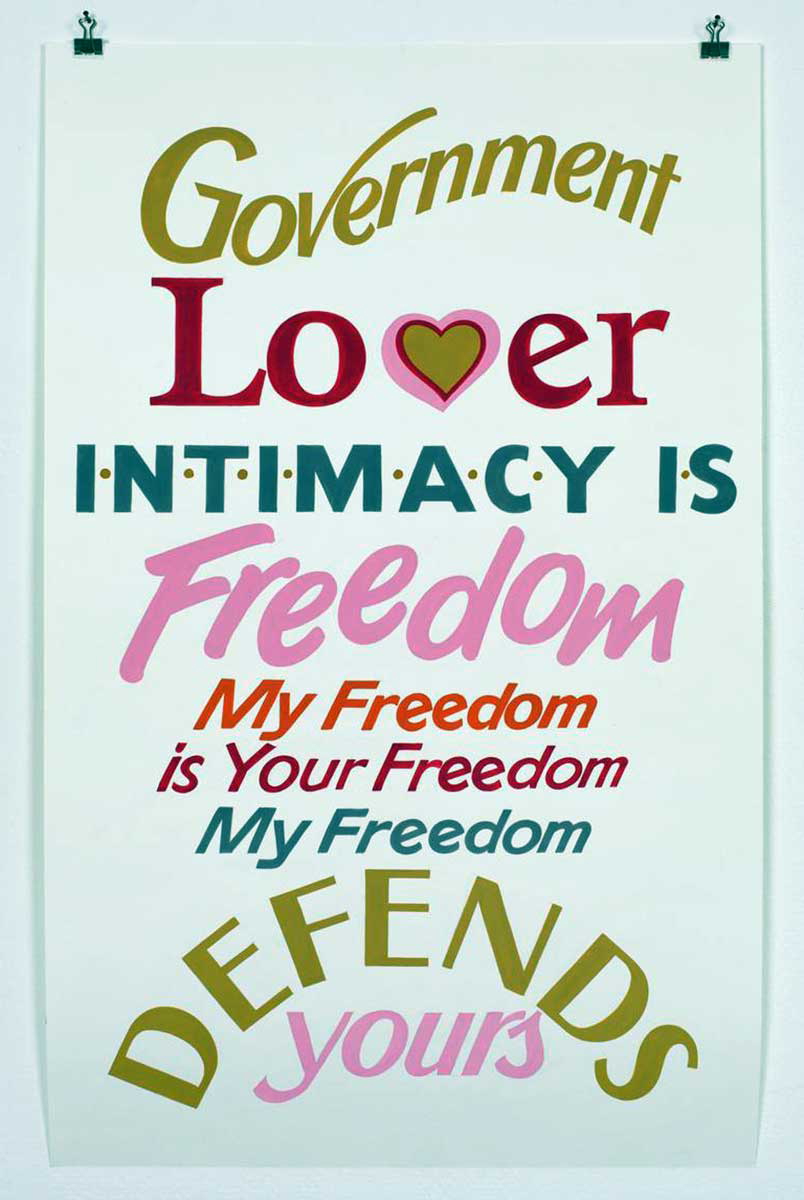

Freedom to Speak?

In liberal democracies, citizens are assured state neutrality on morality and religion. The government offers them equal protection and the freedom to choose how to live within the limits of the law. Indeed, the word “secularism” attests to this desire that in addition to equality and freedom, the state separates itself from religion and asks for there to be only quiet participation of the religious. But some religious individuals consider themselves to be increasingly restricted in the public sphere.

Cancel culture, cyber stalking, trolling, online harassment, social shaming, and several high-profile court cases are some of the punishments meted out to individuals (religious or not) who challenge popular views. Socially-driven emotive ideas which seem to contravene religious morality tend to elicit stronger reactions and ask for the expulsion from the public sphere of those who disagree with the ideas they defend.

The case is that unless limits are placed on what religious citizens can say, i.e., on them making full use of metaphysical and theological beliefs when trying to influence opinions, they may bring into debates standpoints that are not aligned with the ideals of a liberal democracy and that do little to contribute to the social and public policies of progressive states.

As the argument goes, the religious should be allowed to participate in the public sphere only if they are willing to obey the rules of good citizenship. Foremost—and these are de facto rules that could be legislated—is that they leave religion out of political debates.

The Liberally Religious

Some who consider themselves religious are sympathetic to liberal concerns. They accept the limits placed on their contributions. Particularly, that they should participate in public debates only if they keep what they say “within the terms of public reason.” Their view is that “moral integrity” works towards the common good. And as it promotes public order which is “in the interest of the state,” issues may be addressed on the basis of their correctness and their consequences to public order. Not on any religious justification.

This type of Rawlsian argument suggests that individuals retain their human dignity irrespective of how they conduct their lives. From this perspective, state neutrality is justifiable and religious arguments for moral traditions seem less critical.

The secular world, say the Liberally Religious, does not understand the language of faith. And faith does not know how to reason outside of this language. It is okay for the secular polity, characterized by a plurality of religions and moral traditions, to establish values of right and good on its own non-religious grounds.

Religion should be a private matter, an individual’s choice, because religion and politics are different games with different rules. According to liberally religious people, religion and politics do not function well in the same space.

The Strictly Religious

Joseph Ratzinger disagreed. Reason, he said, could easily descend into hubris and “pathologies” if not participating in God’s revelation. Therefore, it must be kept “within its proper limits.” It should “learn from the great religious traditions of mankind” because without religion, the secular conscience is but a “blunt instrument” that can only be sharpened by religious perspectives on, e.g., the transcendentals—beauty, truth, goodness, and unity. Such considerations purify, temper, and influence the shape, content, and themes of public sphere discourses, even if the secular will only accept them on rational grounds.

Moreover, as Nicholas Wolterstorff argued, to ask the religious to exclude their beliefs from political discussions in a social space is censorship plain and simple. Indeed, secular citizens’ “utilitarian or nationalist” views are rarely edited or suppressed in the public sphere so why should the views or texts of the religious be treated in such a manner?

Can Habermas Help?

Although the religious are likely to appreciate Habermas’ willingness to include them in the public sphere, they will be cautious of his ultimate goal to recover meaning without recourse to God. Habermas is a (methodological) atheist. Atheism is a rejection and disbelief in the reality of God or any type of spiritual being, and of any religion purporting to worship such a being. Habermas once saw religious language as a barrier to communication. He felt that religious dogmatic language encouraged people of faith to moralize in absolute terms and to reject the terms of the liberal state.

But by the time of his discussion with Ratzinger, Habermas had a more nuanced view. The secular, he said, should accept religious involvement.

Like an increasing number of secular citizens, Habermas seemed to see value in Judeo-Christian virtues and morality. He also believed that people act on and derive meaning from interaction with each other, and saw this meaning manifesting within the “language-games” we play (these games being speakers’ displays of linguistic mastery) as we attempt to persuade those we disagree with, to concede to our positions.

According to Habermas, “speakers orientated to their own success can influence one another in order to bring opponents to form or to grasp beliefs and intentions that are in the speaker’s own interest.”

What Games

The winner is the more articulate, more empathetic, the one more capable of presenting an argument in a language and in words that are appealing to the listener. So, while the chess master moves pieces around the board to win the game, the linguistic master moves opponents from one opinion to another by providing evidence for claims and using norms to substantiate them. And the desire for the “better argument” dictates the content of the discourse and the approach taken.

But for Habermas, it also makes room for “universal validity claims—truth, justice and ‘the rightness of moral norms’—to be tested” and for a “rationally motivated agreement” to be “achieved … if only the argumentation could be conducted openly enough and continued long enough.”

In short, Habermas’ key motivation for religious inclusion is fairness to all and an interest in the moral questions that the religious may want to raise. But ultimately, he does not see the religious argument as a threat to his atheism or, as is the key concern for secular citizens, to Church-State separation. Therefore, the religious may be disappointed to know that their admittance into the public sphere seems possible, on Habermas’ thought, only because their position is considered untenable and unpersuasive enough to have any real impact.

Habermas’ Atheism: But What About Truth?

In sum, Habermas argued that the religious can and should participate in the public sphere. If they speak with the secular for long enough, reason will most definitely prevail over their faith-based arguments while they will learn more from the perspectives they disagree with.

The obvious inference of this admittance is that with time and the appropriate words used in the right way, the religious can be shown the fallacy of their claims through the consensus that their secular interlocutors will, Habermas indicates, inevitably achieve if speaking for long enough.

Consensus is very far from objective, absolute, or any fundamental truth. For example, at one point in time large numbers of people believed themselves right to use slaves, and a majority of thinkers once thought the world was flat. But Habermas was of the opinion that, if they participated in public sphere debates, the religious would be more likely to concede to secular arguments than to continue their pursuit of objective truth.

If rationalization and reason are such that consensus is certain despite the faith-based arguments (and heart-felt beliefs) of the religious, their inclusion should not be a cause for concern. Indeed, it is crucial if there can be anything that is truly and authentically “democratic.” For Habermas then, on this basis alone, the public sphere needs religion.

But of course, for believers like Ratzinger, without religion in the public sphere society would be adrift in a chaotic sea of anything goes. So long as the participating majority agree to it.