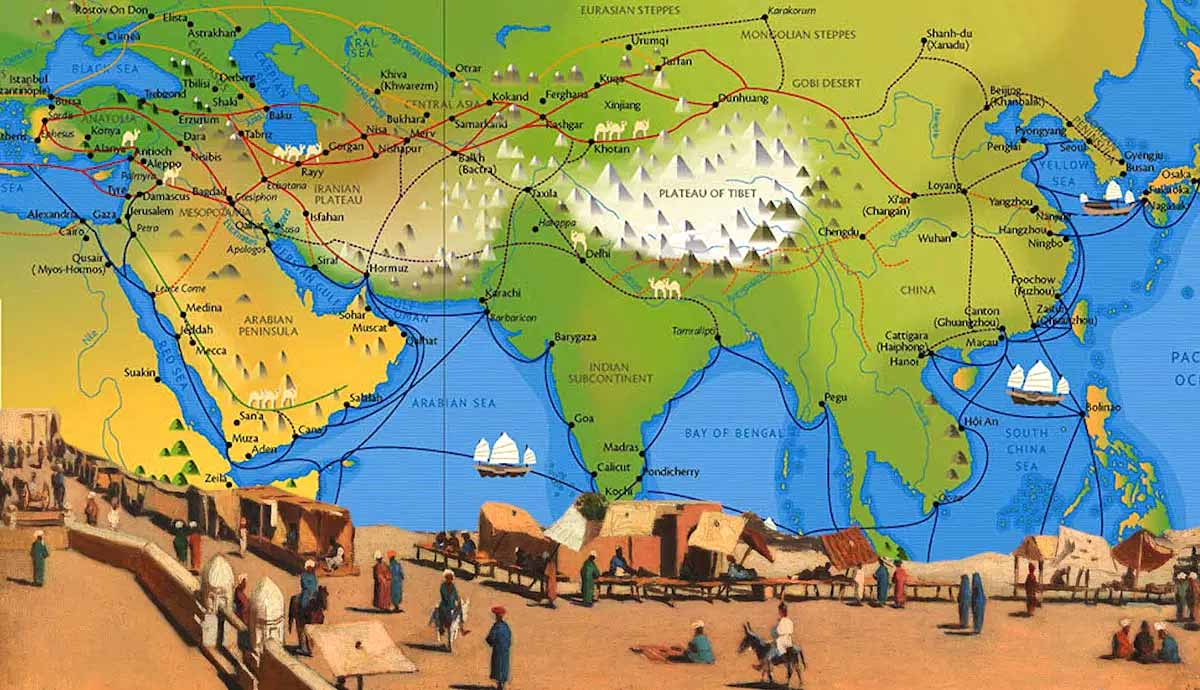

The Silk Road connected Asia and Europe through a complex network of overland routes spanning Central Asia. From Han foundations to a Tang-era peak, it facilitated the movement of goods, people, and ideas on an unmatched scale. These are the ten largest hubs by peak urban scale and overland trade weight—where they were, when they reached their peak, and why they mattered.

What Was the Silk Road?

Spanning Central Asia, the Silk Road linked the economies and courts of Asia and Europe. Travelers and traders came from areas such as present-day China, Iran, Türkiye, Greece, and Italy, all of which were part of the Silk Road. The roots of the Silk Road go back to the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE–9 CE). However, it was during the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE) that the Silk Road experienced its greatest international activity.

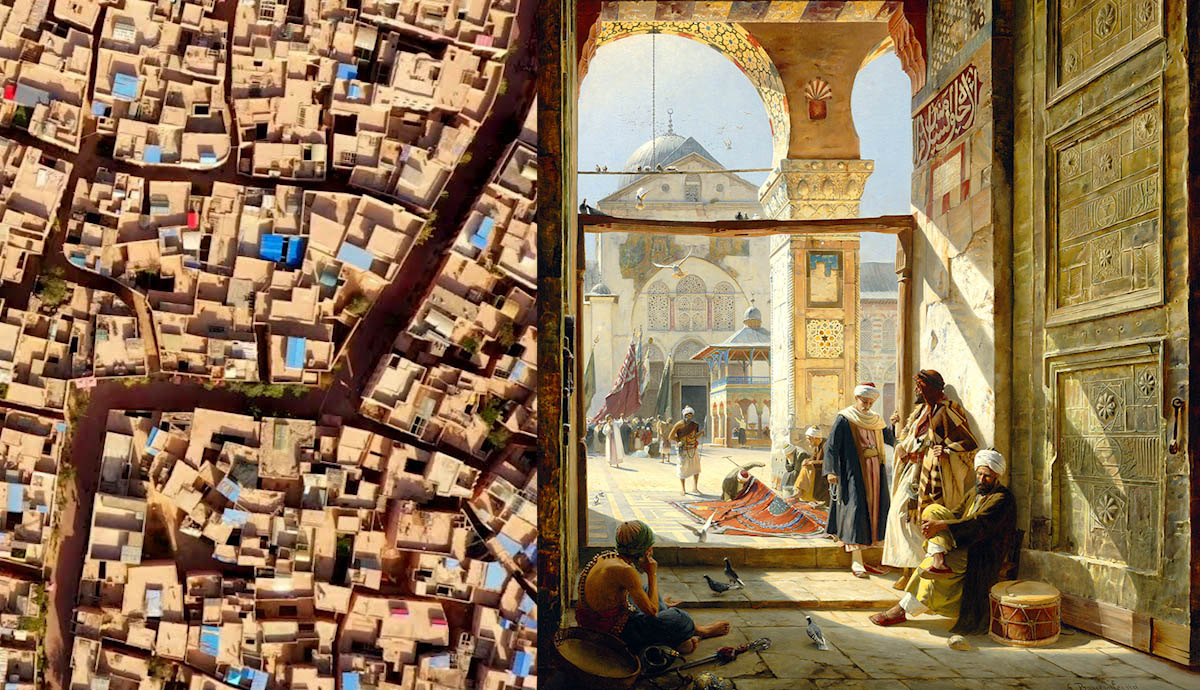

From archaeological finds and surviving texts, especially those discovered in the last two decades, there is evidence of an almost incessant flow of goods and ideas across Eurasia. Porcelain, silk, paper, and gunpowder traveled from East to West, while chariots, wool, glass, and wine came into China. Even ostriches and rhinos found their way to the Chinese imperial court in Chang’an. The linking of diverse foreign lands made the Silk Road a melting pot of cultural fusion, and this was no more evident than in the cities that developed along the ancient trade routes.

1. Chang’an

With more than a million inhabitants at its height, Chang’an was among the largest cities in the world and a magnet for foreigners arriving overland. During the Tang Dynasty, the city’s two great markets divided roles: the Eastern Market catered to the imperial household and aristocrats, while the Western Market was open to the public and was best known for its foreign goods. There, jewelry, silk, tea, exotic herbs, and rare medicines drew crowds, and fashions arriving by caravan quickly shaped local taste.

Key Takeaways: Chang’an

| Location | Xi’an, China |

| Peak era | Tang dynasty (7th–9th centuries CE) |

| Why it mattered | Capital-level hub for politics, culture, and long-distance trade |

| Signature sites | Western Market (foreign goods) and Eastern Market (elite buyers) |

| Trade focus | Silk, tea, spices, jewelry, rare medicines |

2. Dunhuang

For over a thousand years, Dunhuang was a pivotal hub for commerce, culture, and military activity on the Silk Road—an oasis at the western end of the Hexi Corridor. After Emperor Wu’s forces defeated the Xiongnu in 121 BCE, Dunhuang became a center for imperial movement and exchange despite slow travel, difficult communication, and a harsh desert environment.

Dunhuang was also the first major gateway through which Buddhism entered the East. Zhu Fahu and his disciples translated scriptures here during the Jin Dynasty (265–420 CE), and the monk Lezun excavated the first Mogao Grotto. In 1907, the earliest dated printed book, the Tang-era Diamond Sutra, was discovered at Dunhuang.

Key Takeaways: Dunhuang

| Location | Dunhuang, Gansu, China |

| Peak era | Han to Tang dynasties (2nd century BCE–10th century CE) |

| Why it mattered | Strategic desert waypoint and early Buddhist gateway to the East |

| Signature sites | Mogao Grottoes; Diamond Sutra cache discovery |

| Trade focus | Transit of silk, scriptures, and devotional art |

3. Kashgar

Kashgar, often described as China’s “Wild West,” long served as the interface between Central Asia and China. It was an assembly point for caravans bound west toward Samarkand or east across the Taklamakan Desert. According to legend, Emperor Wu sought the region’s “blood-sweating” heavenly horses for the Han armies, opening the way beyond the desert. Chinese control was intermittent over the course of two millennia, and the Uyghur minority has remained the local majority in the oasis.

In the last century, Kashgar stood at the center of the “Great Game” between England, Russia, and China. Diplomats, officers, archaeologists, explorers, and agents crowded the bazaars, where languages and interests overlapped.

Key Takeaways: Kashgar

| Location | Kashgar, Xinjiang, China |

| Peak era | Han dynasty onward, with peaks in medieval and early modern periods |

| Why it mattered | Caravan junction before choosing north or south rim of the Taklamakan |

| Signature sites | Old City bazaars and caravan yards |

| Trade focus | Horses, jade, hides; intelligence and diplomacy during the “Great Game” |

4. Samarkand

The Sogdians, now often forgotten, organized much of the transcontinental luxury trade that enriched Tang China. By the end of the 1st millennium BCE, they had built fortified cities such as Samarkand (Maracanda), set on a plateau at the western tip of the Alai Mountains. Founded around 2,750 years ago, Samarkand was conquered by Alexander the Great, Genghis Khan, and Timur (Tamerlane), yet commerce continued to persist.

Between the 6th and 8th centuries, Sogdian merchants created Asia’s largest trading empire. Their success rested on languages, a religiously open outlook—Zoroastrian in many communities, but receptive to Buddhism, Christianity, and Manichaeism—and an ability to adapt quickly to new political conditions.

Key Takeaways: Samarkand

| Location | Samarkand, Uzbekistan |

| Peak era | Late antiquity to medieval era with strong Sogdian phase (6th–8th centuries CE) |

| Why it mattered | Sogdian merchant capital organizing long-distance luxury trade |

| Signature sites | Sogdian urban core and workshops |

| Trade focus | Cut stones, fine metalwork, textiles tailored to regional tastes |

5. Balkh

Known as the “Mother of Cities,” Balkh was once a hub for trade and belief across the region. The city is located approximately 22 km (13 mi) west of Mazar-i-Sharif, on the banks of the Balkh River. Alexander the Great fought here and married Roxanne, the princess, soon after.

In the early 7th century, before the Arab invasion of Persia, the Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang noted the presence of many Buddhists in Balkh. Zoroaster was said to have been born here and perhaps died here. Centuries later, it was also the birthplace of Rumi, and some traditions hold that he was buried here.

The city was devastated in the 1220s when Genghis Khan’s forces razed it.

Key Takeaways: Balkh

| Location | Balkh, Afghanistan |

| Peak era | Antiquity to early 13th century (pre-Mongol sack) |

| Why it mattered | “Mother of Cities”; crossroads of belief, letters, and power |

| Signature sites | Bactrian walls and later shrines |

| Trade focus | Caravan crossroad for Bactria; flow of scholars and pilgrims |

6. Merv

Merv, east of Mary in Turkmenistan’s Karakum Desert, is one of Central Asia’s most important historical sites. It appears in Achaemenid-era sources, and by the 12th century, it rivaled Damascus, Baghdad, and Cairo as a major Islamic center. The Parthians, Sassanids, and Seljuk Turks all left their mark, and the city’s growth created a layered urban landscape of forts, palaces, and religious buildings; the oldest surviving structure, El Kekara, dates to the 6th century BCE.

In 1218, the Mongols demanded tribute. After the envoy was killed, Tolui led an army that in 1221 razed Merv, massacred its population, and left a thriving metropolis in ruins.

Key Takeaways: Merv

| Location | near Mary, Turkmenistan |

| Peak era | 12th century (major Islamic center under the Seljuks) |

| Why it mattered | Junction linking Central Asia and Persia; court, colleges, caravan quarters |

| Signature sites | El Kekara fortress; Great Kyz Kala monuments |

| Trade focus | Regional redistribution of goods along east-west routes |

7. Ctesiphon

Ctesiphon, on the Tigris southeast of Baghdad, served as the capital of the Parthian Empire and later the Sassanid Dynasty. The Romans held it at times; the Sasanian state made it a seat of power until, in 637 CE, Arab armies captured the city and used it as a base for conquering eastern Persia.

Though only ruins remain, such as mud-brick walls and vestiges of palaces, Ctesiphon’s scale is still clear at the Taq Kasra, the vaulted hall of Khosrow I. Its unreinforced brick arch rises about 100 feet and is the tallest single-span brick vault in the world.

Key Takeaways: Ctesiphon

| Location | near Salman Pak, Iraq (SE of Baghdad) |

| Peak era | Parthian and Sassanid periods (fell to Arab forces in 637 CE) |

| Why it mattered | Imperial capital and Silk Road powerhouse of administration and ceremony |

| Signature site | Taq Kasra hall (tallest single-span brick vault) |

| Trade focus | Regional redistribution of goods along east-west routes |

8. Palmyra

Set in an oasis on the edge of the Syrian Desert, Palmyra connected the Persian Gulf and Asia with the Mediterranean and Europe. From the 1st century CE, it grew rich as a trading center. Merchants brought Chinese silk, pottery, and herbs through Syria in exchange for glass, dyes, and pearls.

Often called Syria’s “Pearl of the Desert,” Palmyra experienced rapid expansion under Roman rule, reaching its peak in the 2nd century CE. In 1957, workers building an oil pipeline uncovered a catacomb linked to Queen Zenobia (c. 240–274 CE), who broke from Rome to establish the Palmyrene Empire. Rome destroyed Palmyra in 273 CE. However, the city’s colonnades, towers, tombs, and temples still cover roughly 2.3 square miles.

Key Takeaways: Palmyra

| Location | Tadmur (Palmyra), Syria |

| Peak era | 2nd century CE under Rome; brief independence in the 260s-273 |

| Why it mattered | Entrepot taxing and protecting east-west caravans across the steppe |

| Signature sites | Colonnaded avenues and temples, including Baalshamin |

| Trade focus | Silk, dyes, glass, pearls moving between Asia and the Mediterranean |

9. Damascus

Damascus sits at the foot of Mount Qasioun, where the Barada’s tributaries feed gardens and workshops. Chinese silk was being processed here by 115 CE: bolts were dyed and finished to suit Roman markets, then shipped to Rome and sold locally. Several caravanserais survive near the Old City souqs. With animals stabled below and rooms above, their open courtyards served as trading floors, an arrangement once common along the route and still legible in Damascus’s lanes.

Key Takeaways: Damascus

| Location | Damascus, Syria |

| Peak era | Long continuity; notable early silk processing by 115 CE |

| Why it mattered | Processing hub adapting Asian silks for Roman and Mediterranean markets |

| Signature sites | Old City caravanserais near the souqs |

| Trade focus | Silk dyeing and finishing; regional redistribution |

10. Constantinople

Known in the past as Constantinople, Istanbul has served as the capital of the Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman empires and, briefly in the early republic, as the capital of Türkiye. It was renamed Constantinople in 330 CE and became Istanbul after the Ottoman conquest in 1453. In 1923, the new republic moved the capital to Ankara, yet Istanbul remained the country’s largest city.

Historically, Constantinople was a commercial hub and the indispensable route for merchant ships from Black Sea ports. Built at the meeting point of Asia and Europe, it is often considered the terminus of the Asian overland Silk Road.

Key Takeaways: Constantinople

| Location | Istanbul, Türkiye |

| Peak era | Late Roman/Byzantine to Ottoman (4th–15th centuries CE and beyond) |

| Why it mattered | Imperial capital and customs chokepoint for Black Sea-Mediterranean trade |

| Signature sites | Golden Horn harbors and customs houses |

| Trade focus | Grain, timber, and luxury goods; taxation and brokerage |

Modern Cities on the Silk Road

In recent years, China has revived the idea of the Silk Road through the “Belt and Road Initiative,” developing overland and maritime routes to boost connectivity. The corridors run through more than 60 countries. Cities seeing major change include New Lanzhou, Wuwei, and Khorgas (China), Aktau (Kazakhstan), Gwadar (Pakistan), Anaklia (Georgia), Istanbul (Türkiye), Duisburg (Germany), and Rotterdam (Netherlands).

FAQs: Largest Cities of the Silk Road

Q: What does “largest” mean here?

A: Biggest at their peak in people, trade, and government importance.

Q: Was the Silk Road a single road?

A: No. It was a network of routes that changed over time.

Q: When did the Silk Road reach its peak?

A: It began in the Western Han (202 BCE–9 CE) and peaked in the Tang Dynasty (618–907 CE).

Q: What moved along the routes besides luxury goods?

A: Ideas, religions (like Buddhism), people, technologies, and texts.

Q: Why did some great cities decline or fall?

A: War and conquest, routes shifting, and, later, the rise of sea trade.