Charles Baudelaire was one of the most influential writers in all of French literature. Admired by compatriots and contemporaries in the 19th century, such as Victor Hugo and Gustave Flaubert, Baudelaire has since enjoyed a long and widespread popularity. His poetry spread and helped spawn later literary movements such as Symbolism and decadence. His work was all the more influential because it was censored for profanity. But who was the poet behind the shocking verses about sexuality, pestilence, and death?

Baudelaire Was a Well-Off, Well-Educated Young Man

Baudelaire was born in Paris in 1821 into a relatively well-to-do family, with a civil servant father who was considerably older than his mother. But the formative aspect of his upbringing came in 1827, when his father died, and his mother remarried a military lieutenant.

From this point until he came of age at 21, Baudelaire was shaped by the knowledge that he stood to inherit a decent fortune, but until then had to behave well and get along with his mother’s new husband, Colonel Aupick. He mostly managed to do so throughout his school years, although, despite being very able, he found it difficult to apply himself because he felt he lacked a purpose or vocation.

By the time he finished high school, Baudelaire was mixing in Paris’s literary circles and beginning to rack up debts, so his family was determined to send him on a long journey abroad. Undeterred, Baudelaire jumped ship and returned to Paris. From then on, he set himself in opposition to his family’s interventions. After turning 21, he began to burn through his inheritance, and his family employed a lawyer to manage his access to the fortune.

Despite his well-off background, Baudelaire would adopt a Bohemian lifestyle for his entire adult life, constrained by financial circumstances but devoted to art and beauty.

He Was a Dandy

Like so many artists, Baudelaire recognized the value of courting publicity, although he may have retained his profligate lifestyle and eccentric affectations even had he not been making early forays into poetry in the 1840s. For Baudelaire, these quirks were part and parcel of the persona of poet which he inhabited, as fundamental to that persona as actually writing verse.

He was conspicuous about his clothing, changed his hairstyle frequently, and lived a peripatetic existence in the various hotels of Paris, including its seedier neighborhoods. He aspired to collect paintings and also spent considerable sums on visits to brothels. Although he went about making literary connections, he evidently followed his own path and felt beholden to no one. This detached individualism, as well as his fussiness about his appearance, made Baudelaire a prime example of a dandy.

All of this experience found its way into his poetry, although at this time, in the mid-1840s, Baudelaire was making more of a name for himself as an art critic, revealing his avant-garde credentials by championing as yet under-appreciated painters such as Eugène Delacroix.

He published a novella, La Fanfarlo, which fictionalized his relationship with the French-Haitian actress Jeanne Duval (later a central figure in his poetry). Although he was writing poems and reciting them to friends, who often found them shocking, he published them only sporadically, and often under pseudonyms.

Was He a Revolutionary?

In 1848, Baudelaire had an episode he would later describe as “mon ivresse de 1848” (“my frenzy of 1848,” or even “my drunkenness of 1848”). This dandy, this well-educated child of the bourgeois who took scrupulous care over his dress and mingled with aristocrats in the pursuit of art collection, took part in a revolution.

During the riots of 1848 in Paris, which led to the overthrow of the Second Empire (mirroring similar insurrections against undemocratic regimes across Europe), Baudelaire actively supported the revolutionaries, writing for a revolutionary newspaper and even joining the barricades. So the story goes, he was heard shouting: “Il faut aller fusiller le général Aupick” (“We must go shoot General Aupick,” the name of Baudelaire’s stepfather).

This last detail may shed light on the surprising fact of Baudelaire’s involvement in the 1848 revolution, especially given that this was the first and only time he got involved in politics. It’s possible to see the entire “frenzy,” as he called it, as his attempt to seize a moment of anti-establishment fervor for personal ends, conflating the establishment with his domineering, military stepfather.

However, the incident is not as atypical of Baudelaire and his politics as it might seem. Although the dandy as a role has been generally considered apolitical, it is difficult to separate Baudelaire’s aesthetic interests in the seamier side of society and its down-and-outs, as well as what he called his “plaisir naturel de la démolition” (“natural pleasure in destruction”), from his participation in a movement devoted to overturning the established order in support of the rights of the common man.

He would later, however, privately write about his distaste for a society ruled by either an aristocracy or a democracy. His ideology tended towards anti-idealism in his fascination with phenomena such as disease, decay, decline, and decadence, which he felt would exist regardless of any political efforts.

He Was a Poète Maudit

There was a long build-up to Les fleurs du mal, which sealed Baudelaire’s reputation in literary history. In the decade leading up to its publication, Baudelaire got his name in print by writing reviews, publishing a handful of poems in magazines, and translating various tales by Edgar Allen Poe into French.

In 1855, another handful of Baudelaire’s poems appeared in a magazine, now bearing the title Les fleurs du mal. Finally, in 1857, these poems (along with others which had previously been published and several new ones) broke onto the literary scene as the collection Les fleurs du mal. Just one month after publication, Baudelaire and his publisher were hauled before a court on the charge that 13 of these poems exceeded the bounds of decency.

The charge was not unfounded, insofar as Les fleurs du mal explicitly sets out to scrutinize the bounds of decency. The speaker of these poems is fascinated by everything we might consider distasteful, but finds beauty in these things. Like the late-19th-century decadent movement which Baudelaire would inspire, Les fleurs du mal takes perverse pleasure in disgust, immorality, and artificiality.

Baudelaire attempted to convince the court that his poems were, firstly, merely a reflection of vice—not a celebration of it—and, secondly, no more scandalous than many other starkly realist works published in France in recent years. Authors like George Sand and Honoré de Balzac had shone a light on all sorts of shocking situations in the name of artistic truth, and they had escaped the censors.

Of all the numerous transgressive themes of Les fleurs du mal, the most objectionable, for the French censors in 1857, were those relating to sexuality, especially the sexuality of women.

Some of Baudelaire’s love poems were about Duval, whose on-again, off-again affair with the poet ended just before the publication of Les fleurs du mal. Others were addressed to various other women of the demi-monde with whom Baudelaire had relationships.

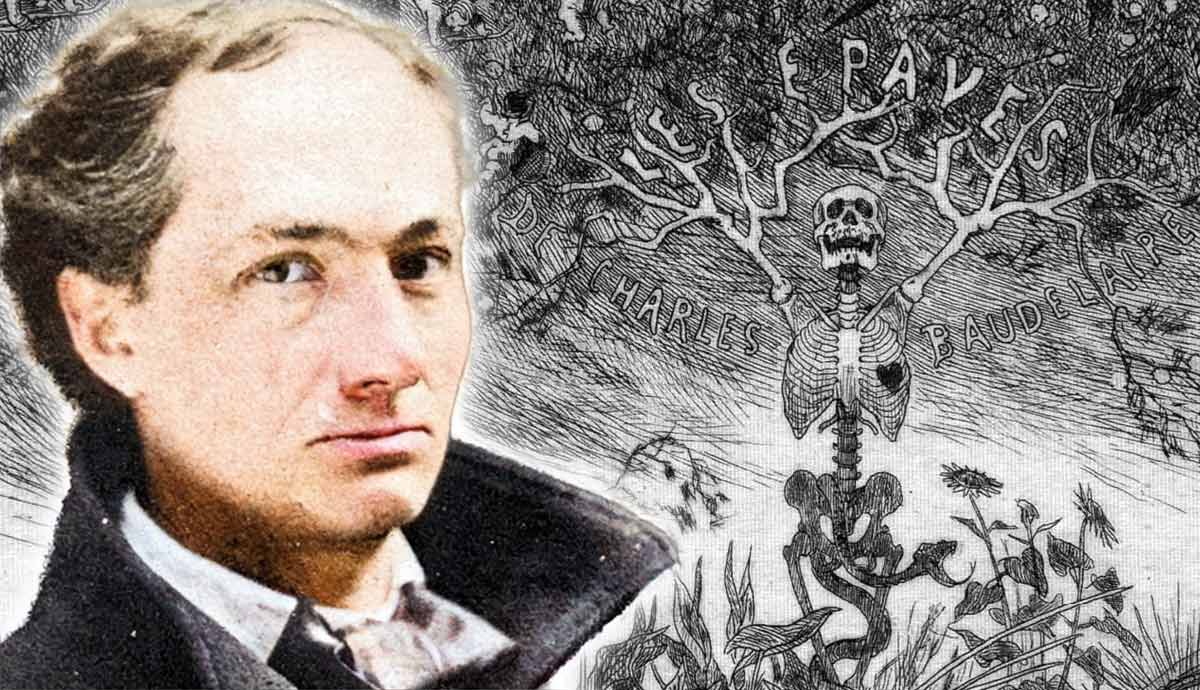

Many of Baudelaire’s poems reimagine women’s bodies as places of disease and decay, rather than fecundity and pleasure. He was ordered to remove six poems from the collection, including one about lesbianism and one about a female vampire. These remained absent from Les fleurs du mal until the ruling was overturned in 1949. (They could be read, however, in a book called Les épaves, or ‘the wrecks,’ published in Belgium in 1866 with a cover illustrated by Félicien Rops.)

This prosecution only aggravated Baudelaire’s conviction, first instilled back when his family had set measures against his profligate spending habits, that all of society was against him. He had anticipated the reaction to Les fleurs du mal in a prefatory poem that accuses his readers of hypocrisy, knowing that all the evils he writes about exist but denigrating him for daring to expose them.

Now considered both a social outcast and a visionary, Baudelaire became known as a poète maudit: literally, an accursed poet, an artist who lives on society’s fringes, diagnosing its ills and refusing to live by its dictates.

He Was a Painter of Modern Life

Along with Les fleurs du mal, Baudelaire’s reputation in literary history was made by his 1863 essay The Painter of Modern Life. While its primary subject is art, Baudelaire offered throughout the essay a definition of modernity that has proved lasting.

Baudelaire’s essay is about the illustrator Constantin Guys. Discussing Guys semi-anonymously as ‘Monsieur G,’ Baudelaire makes observations that would influence the development of impressionism and post-impressionism.

Since Guys was a chronicler of modern scenes such as war and cityscapes, Baudelaire’s discussion opens onto the nature of art’s relationship to the modern. He memorably defines modernity as “the transitory, the fugitive, the contingent, that half of art of which the other is the eternal and immutable.”

The Painter of Modern Life was ahead of its time, offering enduring definitions of various types of people produced by modern conditions: the dandy, the flâneur, and the cosmopolitan.

Dandyism is not, Baudelaire insists in spite of popular opinion, just about fashion and elegance: “To the perfect dandy these things are no more than the symbols of his aristocratic superiority of spirit.” Most of all, the dandy is detached—possessing an “air of coldness that derives from an unshakeable determination not to be moved.”

The flâneur, meanwhile, is a saunterer, a “passionate observer,” who likes to “take up [their] dwelling among the multitude, amidst undulation, movement, the fugitive, the infinite.” This urban wanderer, whose practice was further discussed by the philosopher Walter Benjamin in the essay On Some Motifs in Baudelaire, is more involved with their surroundings than the dandy.

Although the flâneur may not participate in the things they observe, they are intensely interested in everything: both “passionate and impartial” at the same time. They are like an all-seeing eye (or “I,” as Baudelaire writes). Entering the crowd, not drawing back from it like the dandy, the flâneur is like a mirror and a kaleidoscope, reflecting and multiplying everything they see.

Moreover, since the flâneur is by definition someone who moves around, Baudelaire’s definition of this character shades into another which his literary and philosophical successors would elaborate upon: the cosmopolitan. Baudelaire’s definition of the flâneur’s ability to “be absent from home and yet feel oneself everywhere at home” would significantly shape how later artists imagined and idealized their capacity to transcend the limitations of place through aesthetic experience.

Baudelaire Was Struggling in His Later Years

This essay, taken with Les fleurs du mal, became Baudelaire’s definitive statement on modern, especially urban, life, and the place of the artist within it. It solidified his reputation as an avant-garde critic. It could have laid the groundwork for a series of epoch-defining writings, blending verse, prose poems, and essays. However, by the 1860s, Baudelaire was struggling personally and professionally.

His writing was not lucrative, and he often wrote to his mother asking for money, still rankling about her attempts to moderate his youthful exuberance. Like many poètes maudits, he used drugs and paid for sex, and so had an intimate firsthand knowledge of the kinds of diseases he had written about in Les fleurs du mal.

It was ultimately one of these diseases, syphilis, which killed Baudelaire. After a stroke in 1866, he spent a year suffering from paralysis and aphasia (inability to formulate language), dying in 1867. It would be a couple of decades before the decadent movement burst onto the literary stage and celebrated Baudelaire as a forefather, and a few decades more before he was taken seriously as a thinker about the effects of modern urban life on the artist and the individual.