If any figure epitomizes the extremes of German Romanticism in the 19th century, it could be Ludwig II, who ascended to the throne of Bavaria aged 18. Rather than engage with traditional kingly duties—all the more pressing as Bavaria’s political position came into question—Ludwig devoted his reign to building dreamy castles. One of them, Neuschwanstein, has become iconic for inspiring the Disney castle. But he could not live in a fairytale forever.

Bavaria in the Nineteenth Century

Ludwig II was born in 1845 into the ruling family of Bavaria, then one of 39 states making up the German Confederation. Most of these were consolidated into the German Empire following wars between Austria and Prussia in 1866 and France and Prussia in 1871, in which several German states—including Bavaria, under Ludwig’s rule—acted as allies to Prussia.

Situated in the south of Germany, Bavaria borders Austria and Switzerland, and is full of Alpine landscapes: mountains, valleys, lakes, and forests. Ludwig spent an idyllic childhood there, living primarily in Hohenswangau Castle near Füssen. It was the perfect location to stir the young boy’s imagination, and not just because of its geography: Ludwig’s father, King Maximilian II, had built the castle along intricate Gothic lines and had it filled with frescoes depicting medieval German tales. One of these tales, of Lohengrin or the Swan Knight, would become especially dear to Ludwig.

Germany in the early 19th century had been the cradle of Romanticism, a cultural movement that prized flights of the imagination. Philosophical, literary, and artistic works by figures such as the Schlegel brothers, Novalis, Friedrich Wilhelm Joseph Schelling, Heinrich von Kleist, and E.T.A. Hoffmann celebrated the powers of the artistic genius.

They contrasted the artist’s ability to feel deeply with the cold reason of ordinary, unimaginative people. To undertake an endeavor in the name of art, no matter the cost and no matter how ridiculous it may seem to prosaic outsiders, was made noble thanks to Romanticism. It was an exalted, idealistic view of the world that Ludwig II of Bavaria would espouse passionately.

Ludwig II: The Young King

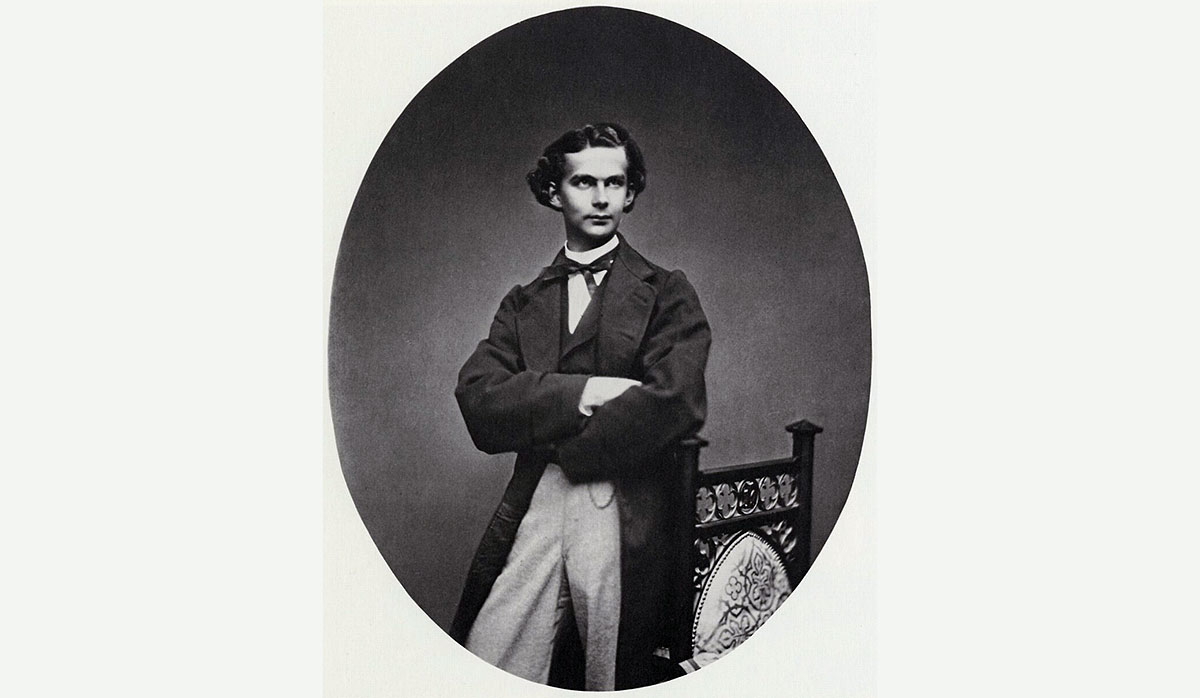

In 1864, Ludwig’s father died, leaving him King of Bavaria aged 18. Maximilian had prepared his son for this through a regime of grueling instruction in royal duties, but it was nevertheless a surprise for Ludwig to come to the throne at such a young age. The regime imposed by his father, with whom he had never been particularly close, left Ludwig uninterested in much of the public show that comes with being a monarch.

Despite his preference for seclusion, Ludwig was popular with Bavarians. He was reported to be a daydreamer who spent hours rambling in the mountains, but this suited the Romantic image of what princes ought to be like. He idolized William Tell, the mountain-dwelling revolutionary of Swiss folklore.

In common with many in Europe at this time, he viewed ancient Greek society and culture as a model for modern life, and eschewed military parades in favor of music and the theater. He found a fellow fan of Ancient Greece in the composer Richard Wagner, striking up a long and significant friendship.

The other model for Ludwig’s reign was France’s Louis XIV. It was not lost on him that he had been named after Saint Louis IX, patron saint of Bavaria, on whose feast day Ludwig was born. This connection spurred Ludwig’s enthusiasm for French monarchs, particularly the extravagant ‘Sun King,’ Louis XIV.

His love of William Tell clearly did not strike Ludwig as being at odds with his admiration for an absolute monarch. Ludwig envisioned himself as the ‘Moon King,’ imitating the great ruler of the Ancien Régime through lavish displays of wealth, taking pleasure in pursuing luxury, spending days sequestered in his palaces and nights carousing by the light of the moon.

The Romantic Ruler

Ludwig’s reign was characterized by a paradox. He despised public life and being the center of attention, but possessed a wealth of characteristics—good looks, a love of the arts, a taste for patronage, conspicuous eccentricities, and wealth itself—which made people inclined to pay attention to him. It was said that, in his youth, he had his hair curled every day, and when he grew old enough to be asked to put on a helmet to participate in the royal military, he declined on the grounds that it would ruin his hair.

He avoided state dinners, preferring (so one story went) to dine with his favorite horse. While these largely benign rumors swirled, more damaging reports circulated about Ludwig’s sexuality. Like any monarch, he was under pressure to marry and produce an heir; he was also a fervent Catholic. Both factors made his attraction to men a source of turmoil.

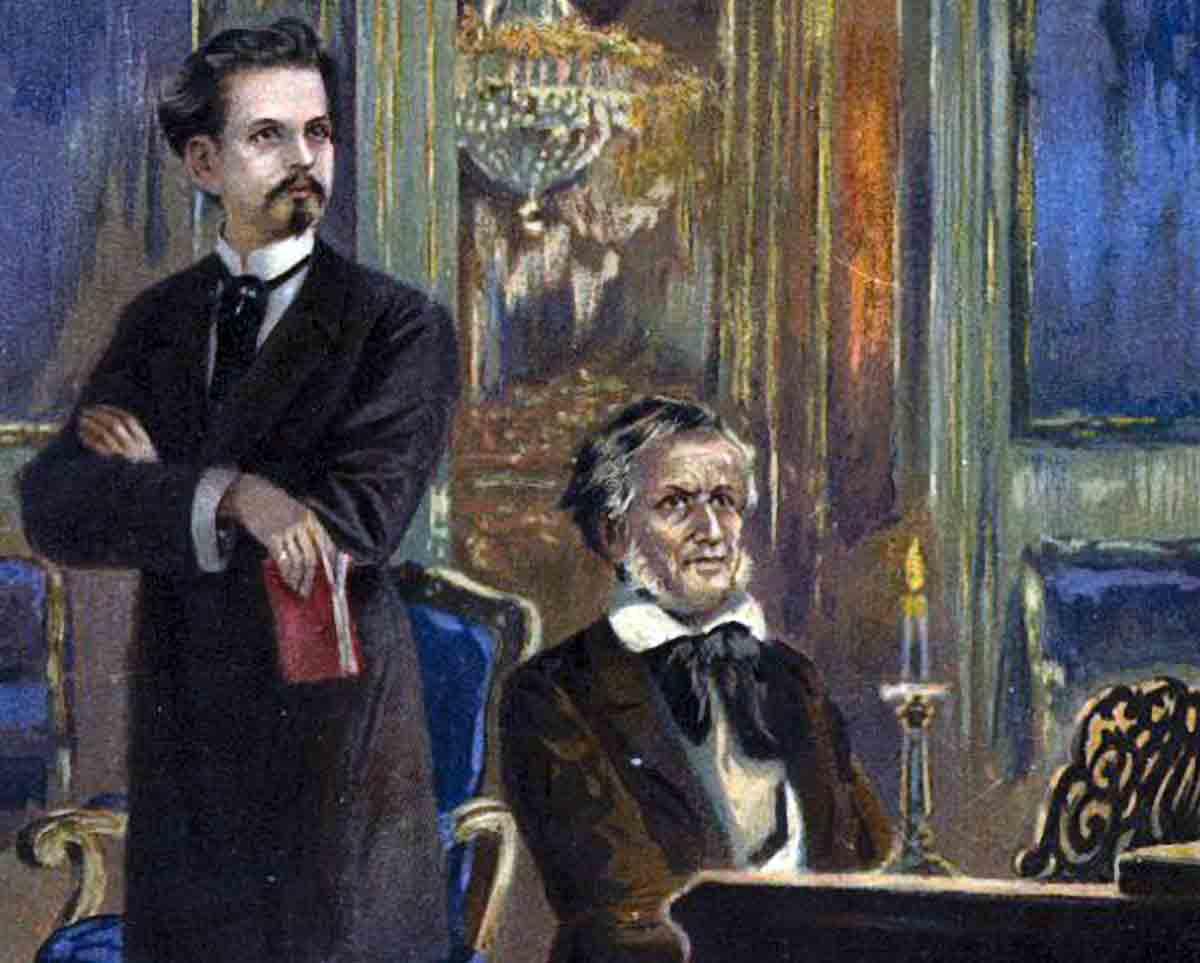

It is possible that Ludwig’s feelings for Richard Wagner, whom he not only befriended but invited to his court and bestowed years of patronage, went deeper than artistic admiration. Although Wagner was 51 and embroiled in an affair with Cosima von Bülow (the married daughter of fellow composer Franz Liszt) when the 18-year-old king invited him to Bavaria, Wagner desperately needed the support offered by Ludwig. He recognized in the young ruler a fellow Romantic who could appreciate his works and would be devoted, come what may, to getting them staged.

For over a decade, the pair exchanged admiring letters, and Ludwig assisted in getting Die Meistersinger, Tristan und Isolde, and the Ring cycle premiered. He lent Wagner money to build his ambitious festival theater at Bayreuth, sharing the composer’s dedication to reviving the spirit of medieval Germany through architecture.

It is unsurprising that, when Ludwig did attempt to comply with the expectations laid on him by getting engaged, he could only find the idea palatable by imagining it in Wagnerian terms. In 1867, he was betrothed to his cousin, Duchess Sophie, a fellow Wagner enthusiast.

However, Ludwig could not bear the pressure of the impending marriage, repeatedly postponing it, and ultimately ending the engagement later the same year. In a letter of lament, he addressed Sophie as Elsa and referred to himself as Heinrich; the names are taken from Wagner’s Lohengrin, which recounts Ludwig II’s beloved Swan Knight legend.

Conflicts and Castle-Building

While Wagner built the theater at Bayreuth, Ludwig spent even more money on his own architectural endeavors. Like Bayreuth, these projects were to usher in a new age of greatness for Germany, inspired by medieval myths and legends, like those Wagner put on stage in his operas, but imbued with a 19th-century Romantic spirit.

The castles at Neuschwanstein, Linderhof, and Herrenchiemsee were inspired by Wagner and Louis XIV. Each was a passion project personally overseen by Ludwig, who wrote to Wagner as work at Neuschwanstein began: “It is my intention to rebuild the old castle ruin of Hohenschwangau near the Pöllat Gorge in the authentic style of the old German knights’ castles, and I must confess to you that I am looking forward very much to living there one day.”

In fact, Ludwig ended up living at Linderhof, which was begun in the same year as Neuschwanstein (1869) but finished earlier, in 1878. The palace at Linderhof was modeled on Versailles, complete with neo-Rococo architecture and pristine gardens. It was also dotted with references to Wagner, with a hut imitating the one used in Die Walküre (part three of the Ring cycle), a hermitage resembling the one seen in Parsifal, and a Venus Grotto based on Tannhäuser.

Neuschwanstein was also Wagnerian, down to its very walls. Ludwig employed set designers, rather than architects, to work on the interior, with several rooms adorned with frescoes depicting scenes from Tristan und Isolde, Parsifal, Tannhäuser, and Lohengrin. The castle’s exterior—nestled among the imposing Bavarian Alps—is just as impressive and instantly became an iconic tribute to the fairytale imagination when its likeness was used for Disney‘s Sleeping Beauty Castle.

As Ludwig’s most ambitious project, however, involving the building of an entirely new palace between the ruins of two medieval castles, Neuschwanstein took longer than anticipated. Ultimately, Ludwig only lived there for a matter of months.

By the mid-1880s, Ludwig’s idiosyncrasy had lost its charm. Twenty years of rule by a fairytale prince had left Bavarians disillusioned, their mountains dotted with half-finished castles and their prospects uncertain. Ludwig may have used his own money, rather than state funds, for his architectural projects, but still, it was hardly beneficial for a monarch to be heavily in debt. He continued to neglect state business, and his ministers set about deposing him on the grounds of madness.

Ludwig II’s Mysteries: Madness and Death

When any historical figure is said to have been mad, we have to consider the time and place in which they lived and how this conditioned their diagnosis: what were the norms in their society from which they apparently deviated? Moreover, how did that society treat those it considered mad, and what motivations might there have been for interpreting their behavior as such?

In Ludwig II’s case, the ministers and physicians who produced a report on his madness certainly had a motivation: to remove him from the throne for the good of the state of Bavaria. They contacted various insiders at Ludwig’s court, and then passed this information to four psychiatrists for corroboration.

As a recent study has pointed out, none of these doctors examined Ludwig, and only one of them had even met the king: neurologist Bernhard von Gudden, who wrote in the report that Ludwig was “teetering like a blind man without guidance on the verge of a precipice.”

The evidence was that Ludwig avoided the public, holed up in his study concocting grand architectural plans, rambling through the mountains, or demanding that theatrical performances be put on for his sole enjoyment. His treatment of those around him could be erratic, with occasional outbursts of petulance or anger.

Most importantly for late 19th-century doctors preoccupied with hereditary degeneration, Ludwig’s younger brother, Otto, suffered from bouts of debilitating mental illness. This was sufficient for the government to agree, in June 1886, that Ludwig should vacate the throne.

Despite the ensuing scuffle, Ludwig was unable to drum up enough protection from the local police and civilians at Neuschwanstein to prevent him from being taken into custody by the authorities, including Dr. Gudden.

What happened next remains shrouded in mystery. Gudden, who was now overseeing Ludwig’s care, accompanied him on a walk around the grounds of Berg Castle, near Munich, where he had been transported. When they failed to return that evening, the search party found both men’s bodies in nearby Lake Starnberg. Although the water around them was shallow, barely waist-deep, they seemed to have drowned.

Although the official ruling was that Ludwig had drowned himself, the political scramble just prior to his death has led to other theories. Perhaps he was trying to escape his newfound captivity and accidentally drowned in the process. Perhaps there was some kind of struggle between the king and the doctor.

Some maintained that Ludwig was murdered. Fishermen at the lake apparently reported hearing gunshots, suggesting that assassins killed Ludwig and then Gudden, who was a witness. This does not quite align with the fact that no gunshot wounds were found on Ludwig’s body, while Gudden’s body showed signs of a blow to the head and strangulation. But then, the drowning theory is also questionable, since the autopsy found no water in Ludwig’s lungs.

Decades later, a Bavarian countess would regale guests with her family’s theory about what happened, and bring out a grisly heirloom: the coat in which Ludwig had died, with two bullet holes in its back. As recently as 2011, a German man in his 60s swore that he had seen this coat on a visit to the countess in his childhood, and joined several others in calling for a post-mortem on Ludwig’s body. In a further twist of fate, though, Ludwig’s coat cannot be scrutinized as evidence: it was lost in a fire, along with the countess herself, in 1973.

Ludwig II’s Legacy

This fairytale king left behind a series of enigmas, from his dreamlike life to the mystery of his death. He was a crowning figure in a century which, in Germany especially, had been characterized by exaltation of the imagination and the power of art. A Romantic poet could hardly have written a better character. His story is a reminder of our tendency to romanticize the fine line separating genius and insanity.

Ludwig II of Bavaria’s brother, Otto, succeeded him in 1886, but never actively ruled due to his poor mental health. Neuschwanstein Castle was never finished exactly as Ludwig had wished, but was completed in a simplified form by the 1890s. Although Ludwig had wanted the palace all to himself, it was opened to the public just six weeks after he died and has generated vast tourist revenue ever since.

The grand building, with its striking mountainside location and ambitious neo-Gothic interiors, is an architectural feat and testament to Ludwig’s extraordinarily single-minded vision. It symbolizes the highs and lows of Ludwig’s reign: an icon of fairytale enchantment and a visual reminder of the obsessive nature that caused his downfall.

Ludwig’s identification with the Swan Knight Lohengrin, only furthered by the king’s untimely death in a body of water, has become a key part of the fairytale which now surrounds him. The unworldly Prince Siegfried, in Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky’s ballet Swan Lake, could be a descendant of Ludwig.

Along with his castles, Ludwig lives on in Richard Wagner’s operas, which are staged every year at Bayreuth and around the world and may have languished as a footnote in music history if not for the king’s patronage. Ludwig and Wagner appeared in an 1881 novel, Le roi vierge, by the poet Catulle Mendès, and ever since, the king has inspired novels, films, and even board games and video games, in which players can take part in Ludwig’s grand architectural projects for themselves.