The Middle Ages is often unfairly characterized as a time of stagnation, with little in the way of cultural achievement. Far from being true, this was an era of cultural advances that still leave modern minds in awe. The most enduring art form of the era was architecture. Towering cathedrals and stout castles made from stone still stand as a testament to the prowess of the medieval craftsman. Three distinct architectural styles emerged over time, each building on the lessons of previous generations to create ever-greater wonders.

Pre-Romanesque Architecture Phase

The earliest and easily the broadest category of European architecture during the Middle Ages was the Pre-Romanesque Phase. After the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476 CE, large, monumental architecture, for the most part, fell by the wayside as lands once administered by the Romans were forced to deal with the chaos of the collapse of central authority. Migrations of Germanic peoples into these lands changed the ethnic and cultural landscape of the continent. One of these groups, the Franks, played a pivotal role not only in Europe’s political history but its artistic and architectural foundation.

The exact start of the Pre-Romanesque phase is hard to pin down, beginning either in the 6th century under the Merovingian dynasty, or in the late 8th century under the Carolingian dynasty. In either case, the start of the movement began with the consolidation of the Frankish tribes under a single dynastic ruler, bringing some political stability to the tumultuous era. The conversion of King Clovis and the Franks to Christianity in the early 6th century led to the building of churches and monasteries with government approval and funding. Similar processes happened in other regions, such as in Anglo-Saxon England and the Visagothic Iberian peninsula. Each region developed its own architectural style based on local customs, those of the Germanic invaders, the influence of Latin Christianity, and available building methods and materials.

While there is no single style of Pre-Romanesque architecture, they do share some common traits. Compared to the later styles, these were simple, usually rectangular structures made from stone. They were made with thick, stout walls and simple flat roofs as opposed to the large vaulted ceilings that would become a hallmark of later eras. The roof was often supported by timber rather than masonry. Openings for windows were difficult to make without undermining the structural integrity of the walls, so these openings were small and let in very little light. The structure was made from so-called rubble walls. These were made from undressed, or unshaped, stone that would be piled on top of one another and held in place with mortar, giving the surface a distinctive uneven appearance. In short, the Pre-Romanesque style is anything that came before the development of the Romanesque style.

Romanesque Architectural Phase

Like the previous era, it is difficult to pin down when the Romanesque phase started, though most scholars place the era’s beginning around the mid-11th century. During this time, Europe saw an explosion in monastic tradition as well as an increase in pilgrimages, which spurred the construction of larger churches and monasteries. As the name implies, the Romanesque period is heavily inspired by the architecture of the Roman Empire, but also incorporates elements from Byzantine, Germanic, Carolingian, and local traditions.

As was the case in the previous era, Romanesque buildings were initially made with thick walls that had small windows in order to preserve the structural integrity of the building. These windows could be in numerous shapes, but were often semicircular arches. This era also saw the start of what would later become known as “rose windows,” which are circular openings that would be divided into segments, though this would not gain much popularity until the later Gothic style.

The primary building material was dressed stone, or stone that had been shaped into regular-sized blocks, which were held together with mortar. Common types of stone used were limestone, flint, or granite, though brick made from clay was used on occasion as well. As the era continued, new methods allowed for higher walls and ceilings, and one of the most profound differences with the prior era was the use of stone supports for the roof rather than timber, which made the building more resistant to fires.

The roof was held up using a rediscovered ancient technology, the barrel vault. This is a series of arches placed next to one another or, more accurately, a single arch that extends over a given space. Though this technique was used in one way or another as far back in time as ancient Egypt, it was the Romans who popularized their use.

Because of the immense weight of the stone, the lateral forces on the arch push the walls outward, causing the walls to give way and the ceiling to collapse. There are several solutions to this problem. The first is to make the walls thicker, which, while inelegant, is the most practical. Another way is to build two or more barrel vaults next to one another, the inner walls supporting each other while the outer walls were reinforced either by thicker walls or buttresses. Another solution to the issue was the creation of groin vaults, which are two barrel vaults that intersect at right angles. This was a popular way to construct churches and cathedrals because the final structure resembles a cross.

Another hallmark of the Romanesque period was the use of columns, which mimic the columns that were found in the ancient world. These were placed at regular intervals and were thick, untapered, and load-bearing structures that supported the roof. Arcades or rows of arches were also common and could be one, two, three, or even more stories in height. The arches in the arcades, just like the windows, were semicircular in form and could be used to improve the structural integrity of the building or could be used as decoration, or both. The carvings on the stonework were usually unsophisticated with simple geometric patterns such as chevrons or lozenges.

Gothic Architectural Phase

If one thinks about medieval buildings, most people’s imaginations conjure up images of the third and final style of architecture, the Gothic phase. There is no hard delineation between the Romanesque and the Gothic phases, with one era blending seamlessly into the other. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted that the era began in the late 12th century and continued for the remainder of the Middle Ages and into the 16th century. The name Gothic was an insult cast by people from later centuries who thought that the style was brutal and barbaric. They named it after the Goths, a Germanic tribe that overran segments of the Roman Empire, hastening its downfall.

As an outgrowth of the Romanesque phase, the Gothic phase took the basic principles of the previous era and magnified them. Arches were still a primary design feature but were changed based on new innovations and engineering discoveries. Instead of the round barrel vault, medieval builders made pointed arches that had less lateral pressure than the round Romanesque arches. The ceilings were supported by ribbed vaults, or stone support, which led to piers and columns. These innovations enabled the building of taller structures that were able to stand with thinner walls. Perhaps the most important innovation was the use of flying buttresses. These are supports on the outside of the building that press against the outer walls, keeping them from collapsing outward.

Because the walls were thinner yet more structurally sound, the outside walls could contain larger windows. The Rose Windows of the Romanesque era were enlarged, and openings were added to the design. These allowed light to fill the buildings, which were mostly churches and cathedrals. These larger windows were covered with stained glass, which gave the incoming light a dazzling array of hues to amaze onlookers.

The stone itself was also used as a decoration. Unlike the earlier eras, where the stone was either undressed or, at most, decorated with simple geometric patterns, Gothic architecture fully embraced stone carving as an artistic medium in its own right. This is the era that created gargoyles, the small statues usually of hideous monsters that are a mainstay of Gothic cathedrals and have continued to be used even into the present day. Columns and other portions of the stone were carved into decorative shapes like flowers and other plant life, statues and reliefs of saints or historic figures, and much more complex geometric patterns. These were decorations for decoration’s sake, and Gothic buildings were designed with aesthetics in mind as much as practicality.

Construction Methods

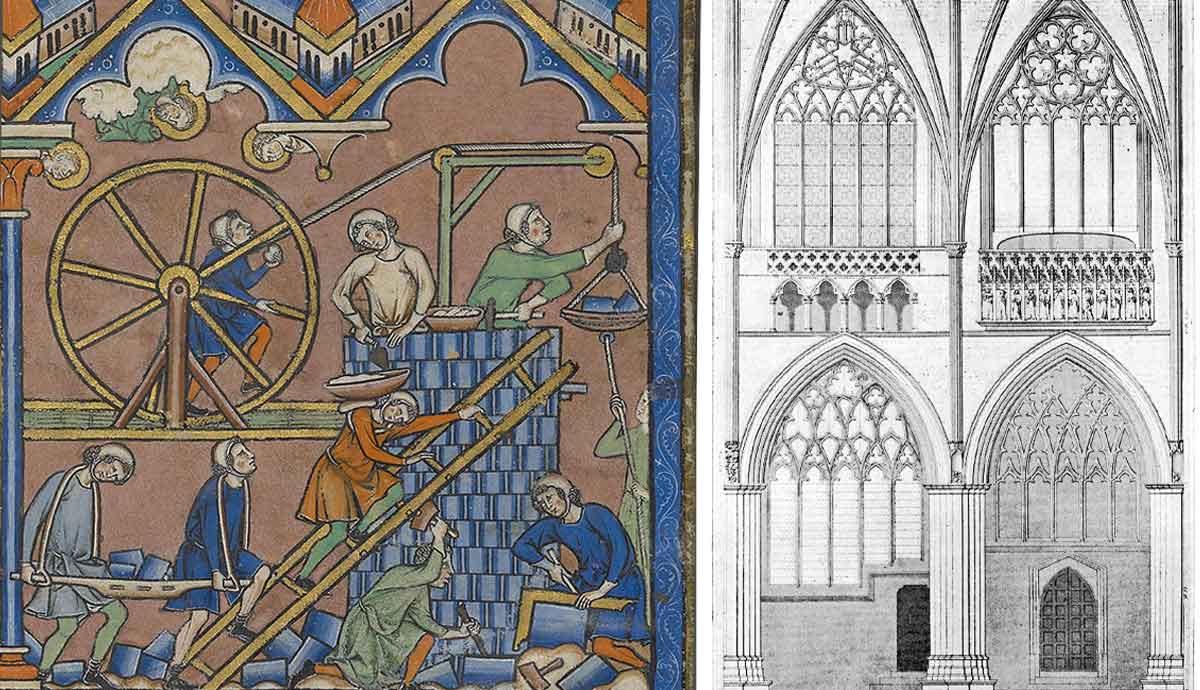

Monumental buildings such as cathedrals were extremely labor-intensive to construct and required workers who possessed incredible skill and dedication. These were often guild members who were held to a high standard of quality. The construction was overseen by a master builder, who delegated the labor to a number of foremen who led the various lower-skilled workers. These included carpenters, mortar makers, blacksmiths, and stone masons. They received their instructions from the foremen and used an array of tools, such as compasses and plumb bobs, to check on their work. Plans were wooden or plaster models that were presented to the local bishop or other Church officials before construction began. Diagrams were drawn or inscribed on the ground, often in the crypt under the structure, as a reference during the building phase.

The stone for the buildings was quarried off-site and transported, often down rivers on barges or overland using oxen wagons. The stone was roughly cut at the quarry and then dressed or finished on-site. Stonemasons cut the individual stones one at a time based on the stage of the construction. Workers then hauled the dressed stone into place, using ropes, pulleys, and ingenious devices such as the treadmill crane to lift the blocks to the appropriate height. Carpenters constructed the ladders and scaffolding needed for the masons, and in some cases, large sections of forest were cleared to keep up with the demand.

Construction was slow and expensive. To ease the financial burden, many cathedrals were built using donated funds from wealthy parishioners. The less wealthy donated their time and effort as common laborers, lending out their draft animals or providing some other service. Relics of saints attracted pilgrims, whose donations contributed to the cost of building a larger or more elaborate building. Even under the best of circumstances, the process was slow, and construction, from the breaking of ground to the finished building, could take decades. It was not uncommon for a cathedral to be started by one generation of workers only to be completed by their children or grandchildren.

The Gothic phase, along with the Middle Ages, would fade away after the start of the Renaissance, which saw ancient techniques rediscovered and a whole new design philosophy created. As new buildings were constructed, the design elements of the previous eras were seen as quaint or primitive, a relic of the past best abandoned. Still, the towering cathedrals and stout monasteries still stand today as a striking visual reminder of the achievements of the medieval era.