Jacques-Louis David was a celebrated Neoclassical painter in France during the latter decades of the 18th century. Although the Oath of the Horatii was commissioned by the French monarchy, David’s subsequent role during the French Revolution—particularly after its “republican turn” in 1791—has muddied the interpretation of the image. In fact, this is a retrospective and false characterization that obstructs the understanding of the image’s virtuous patriotism.

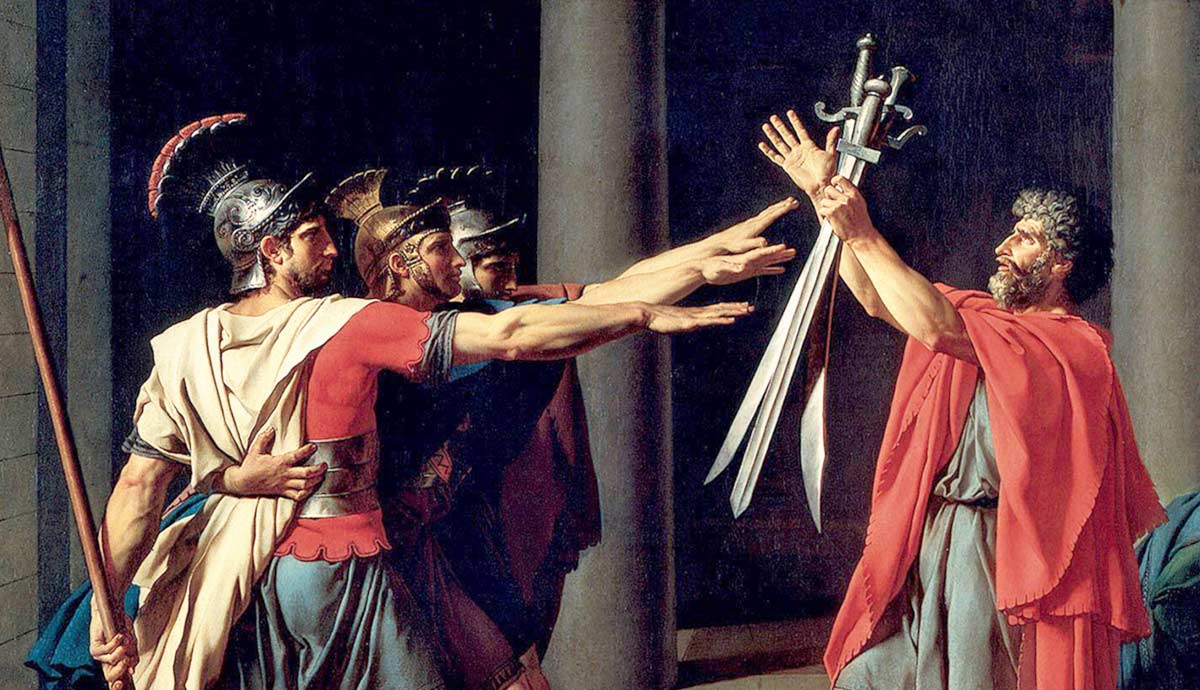

The Oath of the Horatii

The Oath of the Horatii by Jacques-Louis David is a seminal work in the history of European art. It is also the culmination of a moral impulse in European culture during the 18th century and the most refined example until that date of the aesthetic unity of form with subject matter. It is the epitome of what is called—and what was called at the time—the Grand Manner. This means the representation of momentous subject matter with suitable decorum, and with every detail of expression and gesture reflecting the gravity of the content.

The work was exhibited at the salon of 1785 to the Parisian public and was immediately lauded, the crowd “stupefied with admiration.” The picture was seen as the ideal riposte to the previously prevailing style of Rococo in French painting. The Rococo was typified by artists like Francois Boucher and prioritized loose brushwork, sensual themes, and frivolous pleasure. David’s painting was close to the opposite. His art was austere, and many thought that it was the final consummation of a Neoclassical vision that throughout the 18th century was striving to supersede the Rococo.

David’s art was founded upon the moral teachings of ancient Roman authors, especially his beloved Plutarch. He sought in his paintings to create compositions analogous to these writers in the form of an exemplum virtutis, or “example of virtue.” It is in this context that the Oath of the Horatii must be seen—it is only much later, at least as late as 1791, that the image and David’s art in general, was allied to and became synonymous with, the imperatives and ideals of revolutionary republicanism.

The Cultural Background

The shadow cast by Roman antiquity extended throughout 18th-century France. L.D. Ettlinger has observed that, while England and Germany occupied themselves with the study of the ancient Greeks, the French established what he has termed a “cult of Rome.” Roman writers like Cicero, Livy, and Tacitus were promoted and taught in the 18th-century French education system. The historian Plutarch was a favorite author of Jacques-Louis David, who read him avidly. The central themes in Plutarch were duty, the triumph of virtue, and, above all, stoic self-control. These moral imperatives are evident in the Oath of the Horatii.

The ideas of Roman antiquity did not pass down to France unfiltered, however. The 18th century heralded the new ideas of the Enlightenment which foregrounded rational inquiry, and morality without the confines of the Christian Church and ushered in the era of modern science. The writings of the Roman historians and moralists were seen to be at least compatible, and by some, identical with the priorities of the Enlightenment. Enlightenment philosophers agreed that the rational should replace superstition and the traditional pillar of the Church.

The education system in France, through which most artists including David passed, was firmly rooted in the literature of Rome but did not share the Roman emphasis on the cult of the gods. La Font de Saint-Yenne was perhaps the most important cultural influence on the artists of the day. He recommended as subject matter for young artists classical history but also derided the mythological tradition in literature and art as “absurd and immoral.” Painting for La Font de Saint-Yenne must be “a school of morals” depicting “virtuous and heroic action,” especially exhibiting “zeal for honour and love of country.” This was written many years before David’s execution of the Oath but seems like the language of its direct commission.

Another French writer who had a huge influence on the reception and direction of French art at the time was Denis Diderot. Diderot had written dismissively of the shallow levity of the popular Rococo movement in painting, singling out particularly the movement’s most famous exponent, Francois Boucher. Diderot wrote of the need in painting for more “classical severity.” Diderot encountered the early work of David at the Salon of Paintings in 1781. There, David’s Belisarius Begging for Alms was exhibited, and Diderot wrote of the artist: “He has soul,” implying that the picture was sufficiently both classical and moral.

Ettlinger stresses that the French “cult of Rome” in the earlier 18th century did not encompass a political concern, either with Roman institutions or political philosophy. The directions of La Font de Saint-Yenne, Diderot, and others amounted to the moral imperative, and the need to find an artistic language in which to express the Roman ethic. Ettlinger writes that this was the exclusive basis of the French fascination—the political was excluded.

The Narratives

The two principal ancient sources for the story that inspired David are Titus Livius’s Ab Urbe Condita (From the Founding of the City) and the Roman Antiquities of Dionysius of Halicarnassus. Both accounts relate to the war of the 7th century BCE between the young city of Rome and Alba Longa. An agreement is struck between the warring cities that their dispute will be decided by the combat between three of the champion warriors from each side. The Curiatii brothers from Alba are nominated while, for Rome, the Horatii brothers volunteer. David’s moment—the moment of the oath of the Horatii brothers to fight—does not appear in the sources and is an innovation by the artist.

There is a complication in the narrative, as the Horatii’s sister Camilla is betrothed to one of the Curatii brothers, while one of the Horatii brothers is married to Sabina, one of the Curiatii of Alba Longa. As the story progresses to the fight itself, two Horatii are slain while the remaining brother, Publius, achieves victory for Rome by killing the Curiatii one by one after they dispersed in pursuit of him.

It is on Publius’s return that the tragedy of the story intensifies. Seeing his sister Camilla weep for her lost love and cursing Rome, Publius kills her. David thought about representing this moment of the story and even worked on sketches for it, but decided that its gruesome nature would defeat the imperative for the painting of moral action.

Oath of the Horatii

The art historian Anita Brookner sees the Oath of the Horatii as a consummation of an entire “century’s desire for moral sublimity and aesthetic simplicity.” Certainly, the moment that David chooses to represent—the oath to conquer or die out of duty to one’s country—is an extension of an ethic to the point of awe of the sublime. David’s Horatii men on the left and in the center of the composition show a physical inflexibility reflective of a moral one. This is an instance of what Robert Rosenblum has observed of this work’s “fusion of form and ethos.” The men are the epitome of patriotism here. They are unblinking in the face of the consequences of their oath, unified in their purpose, and their taut physical poses show them as unconflicted.

David’s painting has an “all-over” quality—there is not a brushstroke visible. This gives the impression of immediacy and of a presentation of a scene rather than the artifice of representation. The scene itself is austere, without adornment of any kind, and seems to relate a purity of moral conviction and a singular purpose. David’s self-effacement or “technical neutrality” in making the brushstroke invisible relates the action with less of an impediment or a diversion through “style.”

Yet his other pictorial choices make for what Robert Rosenblum calls a “fusion of form and ethos.” Among these choices is a clear recession of lines converging on the weapons held aloft by the elder Horatius and the stark and cool light that reflects the rationality of duty and love of country. Another is the sheer stony surfaces of the architectural setting, whose columns are of the strong and simple Doric order. These choices heighten the seriousness of the moment and exude a direct inevitability—not only of the conviction of the men but also of the tragic and horrific scene in Livy and Dionysius: the murder of Camilla.

Rosenblum writes of the painting’s “electrifying energy and fervour.” This is called for in the image by the content of the story, although the oath itself is David’s invention. The story has a theme of patriotic devotion that extends to the point of self-sacrifice and, in the case of Camilla’s killing, fanatical violence. David distills this extreme emotion into the oath. The cool rationality of the organization of the space and the muted colors is thus in conflict with Rosenblum’s “fervour.” Rosenblum is also right to speak of the “metallic chill” of the colors and of the “rigour and will of the intellect” revealed in David’s setting.

But the motivation for the oath—the defense of Rome until death—is born of and perpetuates an extreme patriotism that reaches a climactic moment in the oath. Despite some interpretations that demarcate feeling and emotion as the preserve of the “female” right side, this is not true. The swearing men betray intense emotion in their very rigid stance, albeit emotion directed towards an action.

Foregrounded to the right of the composition is the female grouping, depicting the grief and pain of Camilla and Sabina. The fact that this group is foregrounded, bathed in the strength of the light falling from the upper left, or included at all, marks a destabilization. The image does not unequivocally concentrate on the male realm of the oath to combat for the defense of Rome. A complication of the ethical status of the oath is the result.

Yet, there is no doubt that formally and tonally the oath is prioritized by David. The physically enclosed shape that the men form to the left bespeaks their unity and undivided will. The shaft of light cast from the upper left illuminates the oath almost as much as it does the female grouping. This is an action, or the commitment to an action, done in the sober light of the felt moral imperative of patriotism.

The fact that the light falls more generously on the female grouping does much to highlight the plight of the women and provokes consideration of their own ethics in the image and narrative. Two affections are depicted by David: the ethic of patriotic duty and the ethic of love and family as the highest good. David does not seek to resolve or make the two complementary. This is because the story itself hinges on this conflict and because there is no doubt that he has the aim of portraying a stern and sublime Roman moral impulse that the French educational system had inculcated throughout the 18th century.

David’s background is de-emphasized and the figures are prioritized. The background is not prominent visually because it is dimly lit and unornamented. However, its three framing arches and its very austerity make it an intensifier of meaning and therefore integral. The arches, two of which are peopled by the men taking the oath, emphasize the patriotic moral imperative. The sworn-upon hilts of the weapons and the elder Horatius’s hands are at the zenith of the figural composition midway under the central arch. The arches are solid, sheer, and unrelentingly heavy, a visual metaphor for the gravity of the oath and the severity of its consequences.

The figures of the brothers overlap—a common motif in the ancient classical frieze. This, in combination with the sequence of the arches, tempts us to “read” the image from left to right as a narrative, from the oath to act to the inertia of sorrow. However, in terms of the vanishing point of the picture, all lines lead to the oath itself. The receding lines of the pavement and the walls are as unequivocal as the undivided will of the men.

The picture is primarily (though not completely, as has been argued) a masculine painting. The oath is the subject, and the rigid male grouping occupies most of the picture space. The weapons are prominent and the enclosed shape of the male group, together with their elevated stance, make for an ethical hierarchy whereby civic virtue is preferred to the private. Steeped in Roman ethics, David creates an image that splices together the civic, public, and patriarchal Roman motivations for action into the single moment of the oath of the Horatii brothers. But also, the artist introduces disruption of the universal glorification of this ethic by virtue of the formal masculine-feminine divide.

David’s women perhaps form a chorus reacting to the action, and certainly, they form a counterpoint, another order of virtue: that of familial love. The poses of the weeping women, especially those of Camilla (in white) and Sabina (in yellow and blue), are premonitory too of the murder of Camilla, for having cursed Rome because of the loss of her betrothed Curiate.

The image is, though, both narrative and non-narrative. We can read it from left to right in the manner of reading a classical frieze—from the oath to the horrified response by the women (and perhaps project beyond this to the death of Camilla). In contrast, the picture seems to converge formally and thematically on the pregnant moment of the oath itself, which becomes in David’s title for the painting emblematic, and representative of the entire impulse for its creation. This moment is the moment eliciting the grief of the women, making the scene more the instant of the oath, rather than a narrative of action in progress.

The three background arches form a pleasing division of the space but also remind of the three brothers of the Horatii, as well as those of the Curiatii. The latter association ties in with the conspicuous foregrounded grief of the women. But two of the arches are occupied by the oath, the central one by the father of the Horatii. The father symbolizes the moral authority of Rome, and of the king, and both of these are conflated with the duty to the country.

Under the “female” arch to the right, there is a further note of destabilization. This area is the preserve of the lamentations of the women but there is a boy dragging from his eyes the protective hand of the matron to the rear. The boy becomes, like us, a witness to the oath, but by an act of will. He is awakening to the masculine, patriarchal demands of civic duty. He is also the embodiment of the cost of such an exacting obligation, being perhaps the son of a Horatii and his Curiatii wife, Sabina.

Afterlife of the Oath of the Horatii

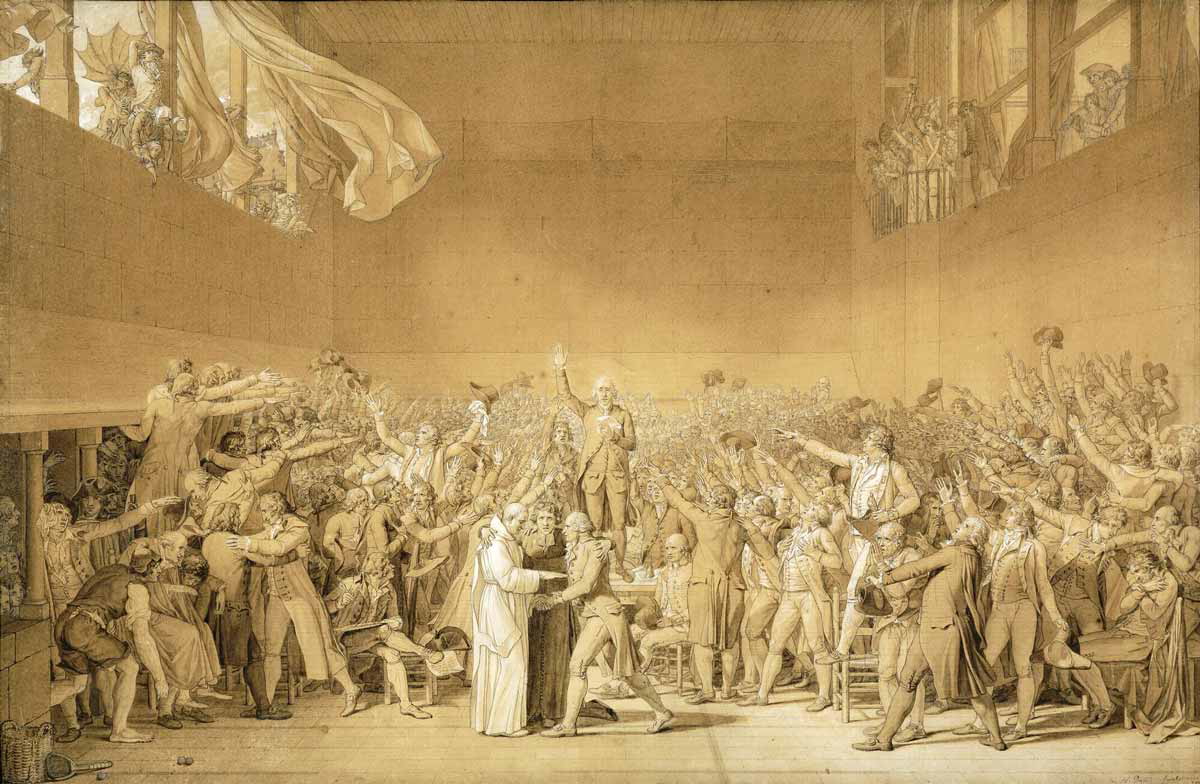

This painting has been made synonymous with the republican ideals of the latter part of the French Revolution, with one contemporary observer remarking upon its “republican pride.” But this is misleading—both the original Roman accounts and the direct context of the painting’s commission and execution were set in a time of monarchy. The French people of 1785 could not have foreseen the events of 1789, nor the belated republican turn of the Revolution after 1791. Contemporary audiences of the writer Voltaire’s play Brutus in the same decade did not see subversiveness in its themes, despite the fact that the titular character sacrificed his own sons in the name of the Roman Republic.

David’s Oath was commissioned by Louis XVI’s assistant Charles Claude de Flahaut de la Billaderie and was conceived as an allegory of loyalty to the French state in the person of the king. The temptation to see subversive intent in the picture is heightened by the knowledge of David’s intense participation in the events of the Revolution. He voted for the execution of Louis. He was closely allied to the leaders of the Jacobins during the period that they led the Reign of Terror of 1793-4. However, current scholarship sees the David of the 1780s as a vastly different character—either apolitical or politically unformed.

It is a surer thing to say that David was radicalized by the Revolution than to say that his radicalism helped to usher it in, in however small a way. In 1785, the Oath of the Horatii was certainly aesthetically revolutionary, but it only became politically revolutionary when the swift course of public affairs precipitated a new ideological standpoint.

Bibliography

Anita Brookner, Jacques-Louis David.

Robert Rosenblum, Transformations in Late Eighteenth-Century Art.