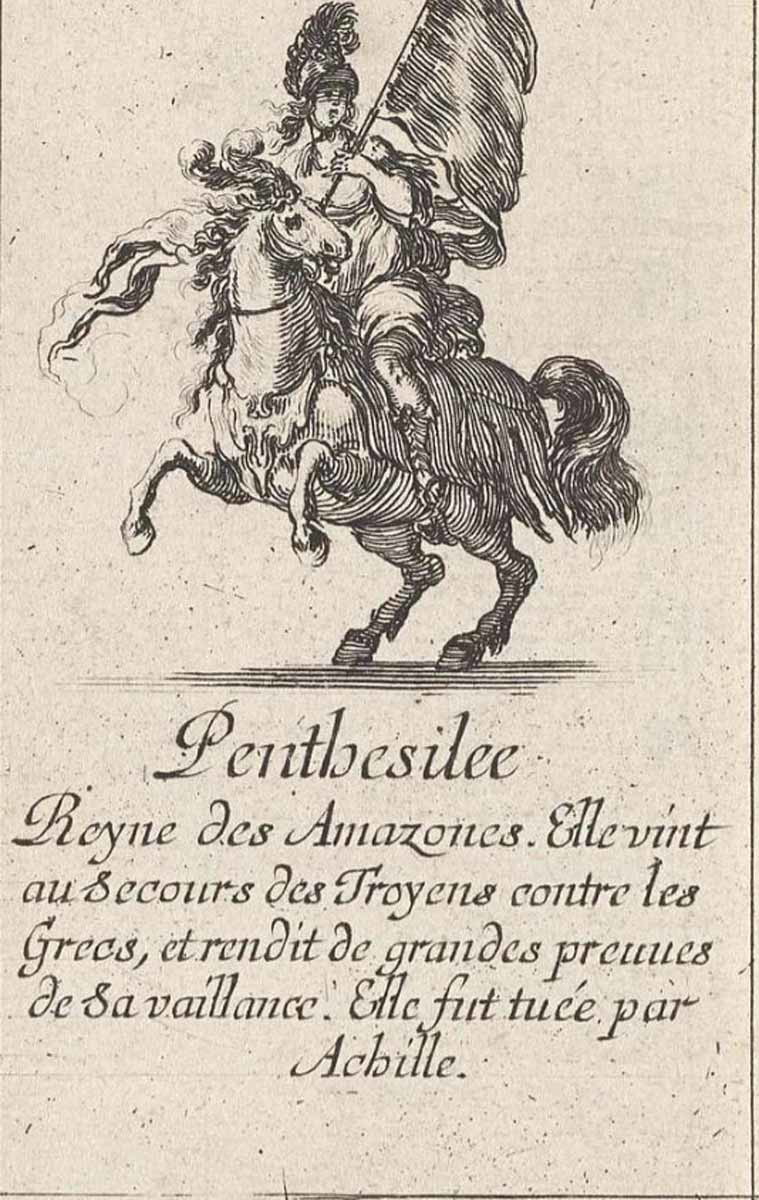

Penthesilea and Achilles: is it a love story, a warning to women who fight instead of homemake, or just more proof that when the ancient world could not explain something, it cooked up some truly out-there myths to fill in the blanks? Let us meet the two protagonists of this war story—both demigods in their own right. On one hand: Penthesilea, Queen of the Amazons, daughter of Ares, battle-ax inventor, and warrior who dared to fight with men. On the other hand: Achilles, scourge of Troy, son of Thetis the sea nymph, and Greece’s deadliest hero.

Penthesilea and Her Sisters

Before Penthesilea rode onto Troy’s battlefield to face Achilles, she ruled over a society that already had Greek storytellers simultaneously fascinated and a bit freaked out. The Amazons, the legendary tribe of warrior women, lived somewhere around the Black Sea—though ask ten ancient experts where exactly, and you’ll likely get ten different answers. Some may say they lived near the Thermodon River, others can cite evidence that points to Scythia or beyond. Geography aside, what really grabbed everyone’s attention was that these women were not just wielding weapons—they were outright winning with them.

Penthesilea was a daughter of Ares (when you invent the battle-ax, you need some impressive lineage), and Otrera, said to be both queen and possibly a consort of the god Hermes. Her sisters were no slouches, either. Hippolyta, famously gifted with that magical girdle that Hercules was tasked to steal as one of his Twelve Labors, is the most well-known. Antiope married—or was abducted by, depending on who is telling the story—Theseus of Athens. Melanippe ended up caught by Heracles and ransomed back, proving that even fearsome Amazons could not escape getting roped into the antics and god-inspired shenanigans of marauding Greek heroes.

Then there is the infamous “one-breast” story. Ancient Greek etymologists loved to claim the name “Amazon” came from a- (without) and mazos (breast), inspired by the legend that these famed archers cut off one breast to draw and shoot better. It is the kind of claim that makes one wonder if the Greeks had ever met a female archer (modern Olympic athletes certainly manage just fine, thank you).

More likely, this myth was part admiration, part cultural anxiety—what better way to use storytelling to ostracize these formidable women than by attributing shocking physical alterations to them? The Amazons defied Greek gender norms by fighting in wars, leading armies, and living without the tradition and strictures of male governance. The breast story was probably just ancient propaganda to make their autonomy seem unnatural. After all, they made each Amazon warrior sound like they chose to be “half” a woman.

Despite the sensationalism, archaeology is beginning to back up a few of Amazonian claims—though not the self-mutilation bit. Uncovered burials across the Eurasian steppe have revealed historical women who were laid in their graves with weapons and riding gear, their skeletons showing signs of a life spent on horseback and in battle. Their bones tell a story of muscle, skill, and years of sustained archery (so much so that it changed the shape of their fingers).

Penthesilea, like her sisters and their escapades, was a symbol rooted in a simultaneous fear and respect for women who dared to not conform.

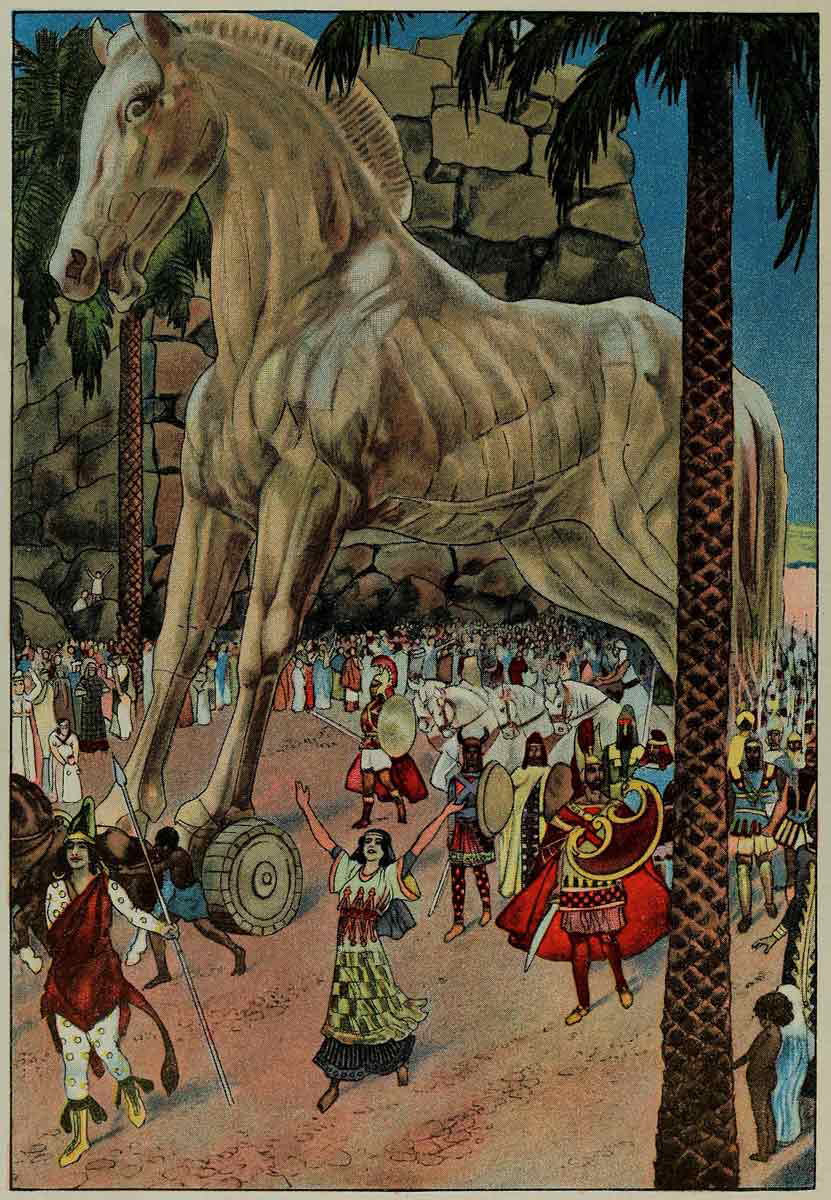

Penthesilea was not destined to remain a regional legend. Some myths say she killed her sister Hippolyta by accident during a hunt or while participating in war games, and the guilt from this accidental slaughter drove her to seek an honorable death (which, for Amazons, could only be achieved on the battlefield). Whatever her motives, she strapped on her armor, rallied her Amazon warriors, and took her female troops toward Troy. Her sisters, her lineage, her legend—they all led her to that fateful battlefield in front of the famous Trojan walls where she would meet Achilles, the Greek hero whose name alone inspired dread.

Two demigods. Two warriors at the height of their power. One confrontation that would be remembered as a warning, a tragedy.

The Prophecy of Achilles

Achilles: The name alone conjures images of battlefield carnage, godlike prowess, and one infamously vulnerable heel. In Greek mythology, few heroes burn as brightly as Achilles, the warrior destined for both unequaled glory and an early grave. His story is central to Homer’s Iliad, which recounts his exploits during the final year of the Trojan War. As with many Greek myths, there is a web of stories behind the legend—tales of divine parentage, impossible choices, and prophecies that refuse to be silenced.

Achilles’s family tree was as complicated as his personality. His father, Peleus, was a mortal king of the Myrmidons—a people said to be peerless in battle, loyal to the last man, and (if you believe certain myths) originally ants transformed into humans by Zeus. Yes, ants.

In one version of the tale, Aeacus, Achilles’s grandfather, son of Zeus, and fellow demigod, prayed for company on the deserted island of Aegina. The gods obliged by turning ants (myrmex in Greek) into a hardy, battle-ready populace for Aeacus to lead. It is an origin story that raises more questions than it answers (Were they still good at carrying twenty times their weight? Did they have an inexplicable urge to invade picnics?), but it certainly explains the Myrmidons’ relentless discipline under Achilles’s command.

If Peleus provided the mortal flesh, Achilles’s divine ancestry came from his mother, Thetis, a sea nymph and Nereid whose maternal instincts went to the extreme. Thetis was determined to protect her son from his all-too-predictable hero’s fate: die young and be remembered forever, or live a long, quiet life doomed to obscurity. Ever resourceful (and more than a little terrifying), she tried several methods to safeguard her son from an early death on some far-flung battlefield.

Some myths claim she routinely placed the infant Achilles on a fire to burn away his mortality, soothing his inevitable burns with ambrosial ointment (“supernatural skincare” was a legitimate immortality strategy). Her most famous attempt to deceive the fates was dunking baby Achilles into the River Styx, whose dark waters granted invincibility. However, Thetis held her precious baby tightly by the foot, leaving that infamous heel untouched by the river’s magic. Thus, the greatest warrior of the Trojan War was rendered nearly invulnerable, with just a single, fatal flaw.

Unfortunately, when Achilles was nine, a seer predicted what Thetis feared most. Despite all her efforts, her son would meet a heroic end fighting the Trojans. Thetis changed tactics. No longer trying to bestow everlasting life, she dressed him as a girl and sent him to hide among the daughters of King Lycomedes on the island of Skyros. Yet, Greek prophecies were not easily avoided. Odysseus, as cunning as young Achilles was fierce, tricked the hidden warrior into revealing himself—depending on the version, by offering a pile of weapons amid feminine trinkets or staging a fake alarm that sent Achilles reaching for a sword rather than a sewing kit. Either way, his life in disguise was over, and he went gladly off to Troy with his Myrmidons in tow.

Despite Thetis’s warnings, Achilles embraced his prophesied fate. He decided he would rather live a short life ablaze with glory than a long, dull existence. That choice—gripping victories over uneventful longevity—would define his story, make his name a curse on the lips of his enemies, and ultimately bring him face-to-face with Penthesilea, the Amazon queen whose journey toward the opposite side of the battlefield echoed his own in more ways than either could have anticipated.

The Meeting of Two Heroes

When Penthesilea and Achilles finally crossed paths on the battlefield, it was less a clash of swords and more a showdown between titans. Achilles, already a legend, had seen the Amazon queen’s talents and was chomping at the bit to prove he was equal to them. Penthesilea, seeking an honorable death to atone for her role in the end of her sister’s life, met him head-on with no illusions about what was at stake. Fate had set the stage. The gods (and poets) watched with bated breath.

But the myths can’t seem to agree on what happened next.

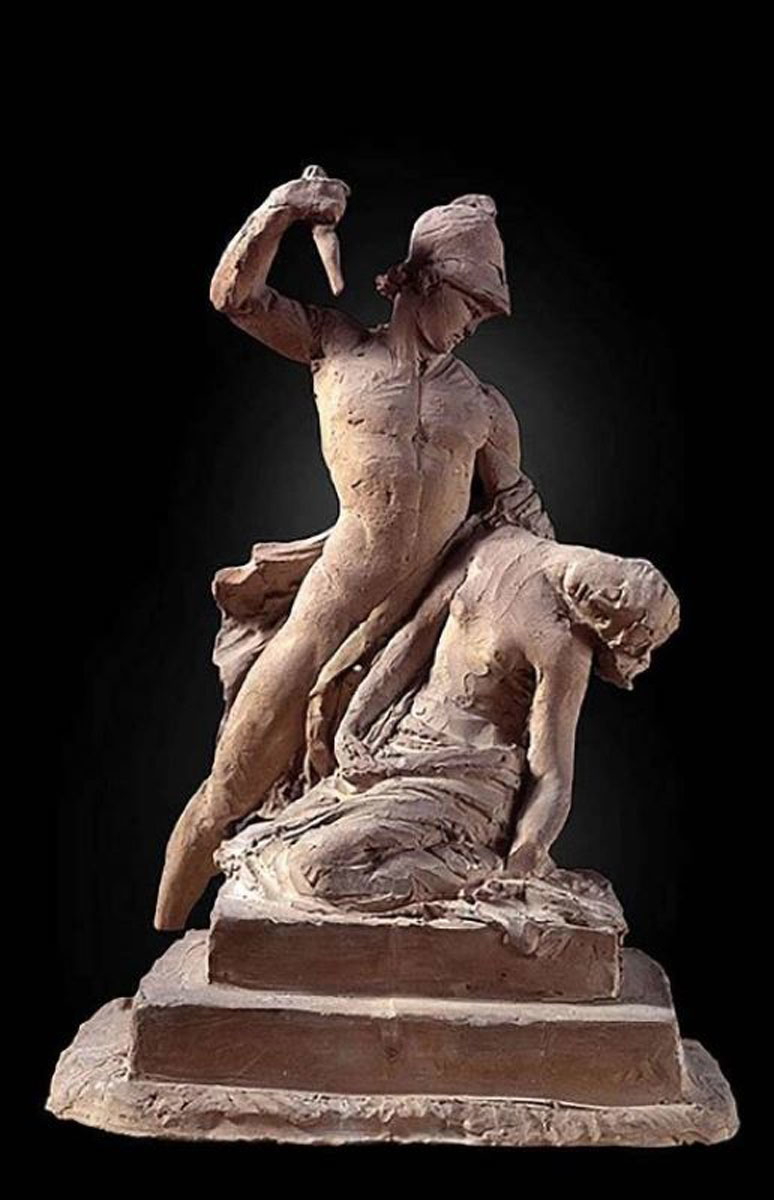

In the most commonly told version, the two warriors exchanged blows that rang over the killing field. Penthesilea, formidable and fierce, managed to land a strike against Achilles’s chestplate, the kind of blow that would have been fatal for any other soldier—no small feat given the man’s near-invincibility. Yet, Achilles, living up to his fearsome reputation, countered with a lethal blow of his own to her heart. As she collapsed, something unforeseeable happened—the man who had been so eager to prove his superiority immediately regretted it.

Quintus Smyrnaeus, writing centuries later, claimed that Aphrodite herself had made Penthesilea “beautiful indeed in death,” so that Achilles—fierce, untouchable Achilles—could be “pierced by the arrow of chastising love” when he removed her helmet and saw her unguarded face for the first time. The irony is almost too perfect: the man no spear could harm was struck down by the goddess of love, using his skill to effectively break his own heart.

Achilles held the Amazon’s still body as the battle continued to rage around it. It was a moment that made his fellow Greeks deeply uncomfortable. Achilles may have had a complicated love life (Briseis, Patroclus, and now a deceased Amazon queen? He was practically a walking tragedy of Greek romance), but this was different. Thersites, the Greek camp loudmouth, took it upon himself to mock Achilles for showing such tenderness toward a fallen enemy. Mocking Achilles had consequences. He killed Thersites on the spot. No one insulted the greatest Greek warrior—not about his emotional attachments, and certainly not in front of the man’s own fighting force.

There is the version where things get very dark. In some macabre tellings, Achilles’s affection for Penthesilea was not tender but twisted—falling into uncomfortable territory where grief and desire blurred in grotesque ways. These later myths suggest that his obsession led him to defile her corpse, a narrative likely more reflective of ancient discomfort with powerful women (and the warriors who respected them) than any actual heroic ideal. Whether that is a cautionary tale, a smear campaign, or just Greek mythology being Greek mythology is anyone’s guess.

There’s also Heinrich von Kleist’s Penthesilea—the 19th-century play that takes the tale of Achilles and Penthisilea and gives it the ultimate twist. In Kleist’s version, it is not Achilles who kills Penthesilea, but Penthesilea who ends Achilles’s life before the walls of Troy. Crazed by love and rage, she not only defeats him but does not stop until she has torn him limb from limb in a frenzy. The original myths portray Achilles’s feeling for his fallen foe, but Kleist gives audiences a reversal so intense it practically howls how dangerous it can be to fall for one of the enemy.

What are modern folk to make of this string of conflicting stories? Is it a love story, a battlefield version of Romeo and Juliet? A warning against hubris? A morality tale about the dangers of humanizing your enemy? Maybe it is all of these. Or maybe, just maybe, it is proof that when the ancient world encountered a woman who could stand toe-to-toe with its greatest hero, it simply could not figure out what to do with her—except perhaps turn her into legend.

Living After Death: How the World Remembers Penthesilea and Achilles

History, and those who are charged with archiving it, has a funny way of picking favorites. Achilles—bronze-clad, rage-driven, and blessed (or cursed) with near invincibility—has lived on through countless retellings, his name synonymous with a cocktail of heroism and vulnerability. Penthesilea? The queen was not quite so lucky. While Achilles is immortalized as Greece’s bravest warrior, Penthesilea often fades into the background of his story, remembered only as that foreign queen he killed.

Achilles’s legend and his bloodline lived on. His son, Neoptolemus (a.k.a. Pyrrhus, “the red-haired”), carried on the family tradition of being both heroic and problematic. Called to Troy in its final days, Neoptolemus fought bravely but committed the rather unforgivable act of murdering King Priam at a holy site. Subtlety and situational awareness clearly weren’t his strong suit. He later married Hermione, daughter of Helen (yes, the world’s most beautiful Helen), but also took Hector’s widow, Andromache, as a concubine—a relationship that produced Molossus, ancestor to the dynasty of Molossian kings. Though eventually, Neoptolemus died at Delphi, his children carried forward the line of Achilles.

Penthesilea’s afterlife in myth and fiction took a different path. Unlike Achilles, whose son remained part of the Trojan story, she did not have an heiress to continue her legacy. Instead, she became a symbol—the warrior woman boldly or maybe naively facing off against the male-dominated narratives.

In modern times, she has been resurrected through the Amazonian warriors of DC Comics. Wonder Woman’s world, deeply inspired by Greek mythology, draws from the same stories that birthed Penthesilea. In Zack Snyder’s Justice League, Penthesilea even appears, guarding the Mother Box and bravely facing Steppenwolf, her sacrifice underscoring the Amazons’ unwavering loyalty and strength. She may now be battling cosmic villains instead of Greek heroes, but her essence remains: a fearless woman standing her ground, self-assured in her skill, in a world that keeps throwing bigger and bigger challenges in her path.

Achilles may be the hero whose name became iconic, but Penthesilea lives on through cultural reinventions—fierce, formidable, and refusing to be just a footnote. Their stories, though centuries old, and yet somehow still intimately intertwined, still ask the same questions: How do we define heroism? And why does history remember some names more loudly than others?